1255 Victoria’s religion of the heart

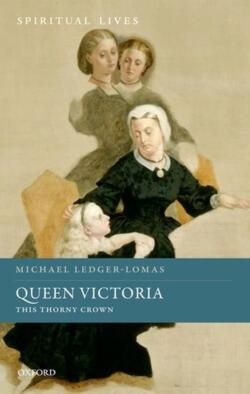

Queen Victoria: This Thorny Crown

by Michael Ledger-Lomas

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021. (Spiritual Lives Series).

$40.00 (U.S.) / 9780198753551

Reviewed by Simon Devereaux

*

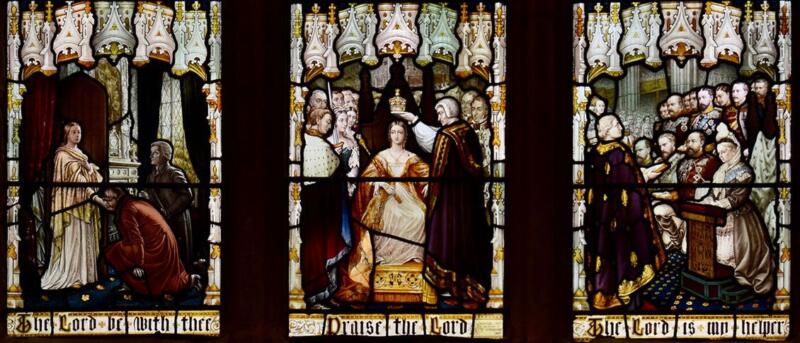

This compact, densely written volume fills a surprisingly large gap in the vast biographical literature on Queen Victoria. The Victorian age is well-known for its public religiosity. It was manifest in the central cultural value placed upon the Home, presided over by a wife and mother who was expected to embody sexless spirituality, and which in turn was believed to be the foundation of the larger stability of society. It was manifest, too, in a self-congratulatory rhetoric that rationalized Britain’s unprecedentedly large global empire as a mission to bring “civilization” – of which Christianity was perhaps the most important facet — to “benighted” peoples the world over.

Michael Ledger-Lomas’s impressive new book shows, in unprecedented detail, how the woman who gave her name to the age strove to embody so many of the spiritual values it professed, with complex and contradictory results. The teenager who succeeded to the throne in 1837 was haunted by the appalling example of her “wicked uncles”: the louche and spectacular spendthrift George IV; and her immediate predecessor William IV, whose similarly excessive appetites were at least largely spent by the time he inherited his brother’s throne in 1830. In self-conscious distinction from the generation of royals that preceded her, Victoria strove to follow the advice, of ministers of state and church alike, to live a life of public commitment to Christian belief. That task was rendered particularly difficult for her because the foremost legal restrictions upon lawful worship in Christian faiths that differed from the Church of England — Dissenters, Catholics — had been relaxed only a few years before her succession to the throne.

Ledger-Lomas reveals how challenging this must have been for a woman who lacked the rigorous intellectual capacities displayed by so many of her senior clergy — and at least one prime minister, Gladstone (whom she heartily detested). In her own public life, Victoria embraced the age’s insistence that women by their natures found their way through the world with their hearts rather than their heads. Ultimately, this proved to be her greatest strength as a spiritual figurehead for her people and her empire. Determined to adhere to a maximally latitudinarian public posture, while personally attracted (somewhat paradoxically) both to the stern simplicity of the Presbyterian faith practiced in her beloved Highlands and to the spectacular outward displays of Catholic worship, the queen often annoyed or alienated, not only senior clerics determined to maintain the authority and privileges of the state church she had sworn to uphold in her coronation oath, but also many of the men determined to expand the right to full freedom of worship for other sects. The latter included Dissenters, who continued to chafe at the remaining constraints upon their own modes of Protestant worship, and whose desire to see the Anglican church disestablished in those parts of the British Isles in which it commanded a negligible proportion of worshippers — Ireland, Scotland, Wales — had a sympathetic hearing from the queen’s Liberal governments of the 1860s onward.

Even in the last years of her long life, Victoria categorically refused to read a throne speech announcing government support for disestablishment in Wales and Scotland, striking a major blow against a Liberal government already on the brink of collapse. Even more problematic were the populist leaders of Catholicism, especially in the chronically restive Ireland, whose troubles were so often exported to those other parts of the empire to which the people of that stricken and overpopulated island were emigrating from the 1840s onwards. Despite (or because of) the fact that Victoria enjoyed cordial relations with several popes and admired much about the Catholic faith, she could never believe that the troubles in Ireland stemmed from anything other than what she saw as “the heedless and improvident way in which the poor Irish have long lived, together with the wicked agitations … and the deeds of violence they have committed” (p.184).

Nowhere were the paradoxes of Victoria’s spiritual preferences more powerfully apparent than in the excessive grief she displayed for her husband Albert throughout the four decades of widowhood that followed his premature death in 1861. Her perpetual black dress (in an era whose mores prescribed it for only two years), as well as the unending succession of semi-religious memorials and institutions erected thereafter, alarmed members of her family and governments alike, particularly when that memorialization extended to publication by the queen of intimate memoirs of her married life in the Highlands.

Worse still was her later extension of such gestures to perpetuate the public memory of her boisterous Highland gillie, John Brown, an emotional attachment whose precise character and extent remain largely and frustratingly mysterious. For all the concern this caused the men and women who embodied the formal authorities of the Victorian age, however, vast numbers of the queen’s subjects nonetheless seemed broadly sympathetic to her open pursuit of a religion of the heart which burst the tight constraints of doctrinal prescription. Her professions of an open spirit and a maternal care for her subjects, endeared the queen even to the leaders of peoples beyond the realms of conventional Christian belief, including Jews in Britain, Hindus in India, and indigenous peoples in Canada and New Zealand. If Victoria’s lasting resistance to the disestablishment of the church seems somewhat surprising given her personal commitment to a broadly liberal and feeling Christian belief system, that opposition stemmed — as Ledger-Lomas shows — from her deep and abiding suspicion that some narrowly defined sects anticipated undue benefits from such policies.

The details of these complicated stories are navigated effectively by Ledger-Lomas. At times that detail threatens to become exhausting, perhaps especially for readers not well-versed in the varieties of Christian belief. Scarcely a sentence lacks a footnote, testimony to the book’s extraordinarily deep foundations in archival and print sources alike, as well as the author’s formidable capacity to marshal a massive body of evidence to persuasive argumentative effect. But readers with an appetite for the detail, complexity and nuance of an age now long past will learn much from this book. A lasting contribution to our understanding of Britain’s most famous monarch, it is a remarkable debut by a major new scholar of religion.

*

Author Michael Ledger-Lomas is a sessional instructor at Corpus Christi and St Mark’s Colleges at UBC and a visiting fellow in the Department of Theology and Religious Studies, King’s College London, where he was formerly a lecturer in the history of Christianity in Britain — Ed.

*

Reviewer Simon Devereaux is an associate professor of history at the University of Victoria. He has published extensively on the history of criminal justice in late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century England, and teaches courses on the history of eighteenth-century Britain, of the British monarchy, and of homicide and capital punishment in England.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster