1237 Tragic legacies of colonialism

ESSAY: Tragic Legacies: The Residential School System in Canada (1876-1998)

by Lily Chow

*

Editor’s note: Today, September 30, 2021, is the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in Canada. “The day honours the lost children and Survivors of residential schools, their families and communities,” states a Government of Canada website. “Public commemoration of the tragic and painful history and ongoing impacts of residential schools is a vital component of the reconciliation process.”[1]

For this inaugural National Day for Truth and Reconciliation we are pleased to present an essay, “Tragic Legacies: The Residential School System in Canada (1876-1998),” by 周蔡小珊硕士 Lily Chow Siewsan. The foremost historian of Chinese Canadian history in British Columbia, Lily Chow explores the operations of the residential schools that were responsible for causing harm and tragedies to Indigenous people, namely the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit in Canada, and examines the detrimental effects on the lives of the students and their families as well as the damage to Indigenous culture. She addresses the courage and determination of First Nations people in calling for justice and recognizes the work of advocates and support groups who helped in the renewal process up until December 2013, when her essay was written. Chow also acknowledges the pivotal role of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada in assisting Indigenous people in the process of reconciliation.

Hitherto unpublished, “Tragic Legacies” was presented as a talk in May 2014 at Tsinghua University, Beijing, in a session devoted to “Aboriginal and Minority Education Studies: Building Bridges between Higher Educational Institutions in Canada and China.” Thank you, Lily, for allowing us to publish it here – Richard Mackie

*

Introduction.

In the 1980s, many former students of the Indian residential schools (IRS), who called themselves survivors, and their families and community leaders established support groups to launch lawsuits against the Federal Government (hereafter, the Government) and the Christian churches that operated the schools and to disclose the tragedies in the IRS as well as the survivors shocking school experiences in the education system. Their initiatives gained recognition to the effect that the perpetrators came forward to apologize for the damages done (see Appendix I). One of the most publicized apologies was made by the Right Honourable Stephen Harper, Prime Minister of Canada[2]. On June 11, 2008, His Honour officially apologized to the Indigenous people of Canada and declared that “Two primary objectives of the residential school system were to remove and isolate children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions and cultures, and to assimilate them into the dominant culture. These objectives assumed that Indigenous cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior and unequal. Today, we recognize that this policy of assimilation has caused great harm, and has no place in our country.” This message of apology indicates that there were problems and issues in the education system that consisted of a network of boarding schools that began in the early 1880s. All Indian residential schools were to educate the Indigenous children – First Nations, Métis, and Inuit. The schools were funded by the Canadian government’s Indian Affairs Department (IAD or DIA), but were operated by some Christian churches. In 1920, an amendment to the 1876 Indian Act made attendance at a residential school compulsory for all Indigenous children. The last residential school was abolished in 1998. Indeed, the process of assimilation and its impacts left many tragic legacies affecting Canadian society.

The proactive groups and organizations also presented the tragic cases at the hearings of the Canadian Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.[3] Their cases culminated in 2007 with the court approval of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA), the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history.[4]

One of the IRSSA mandates was to establish the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Since 2008, the TRC has held public and private sessions for the survivors to share their personal experiences – their hardship and struggles, sufferings and pains, abuses and humiliation – while they were in the IRS. The TRC also organized national events[5] to provide Canadians with opportunities to learn about the history of the IRS, the practices of the schools that produced negative effects on the students and their families, and the justifications for redress and settlements. It is from these gatherings and interactions with First Nations associates and friends that the author gained understanding of the IRS system and its detrimental impacts on the survivors and their families in the past and present generations. The episodes narrated by the survivors have testified to the existence of the tragedies in the IRS system. Thus, this paper will cover the description of the brief history of the IRS system including the school operations and their curricula in general, document some inconceivable events and tragic incidents, and address the negative impacts on the past and present generations of the Indigenous people and the justification for reconciliation.

A Brief History.

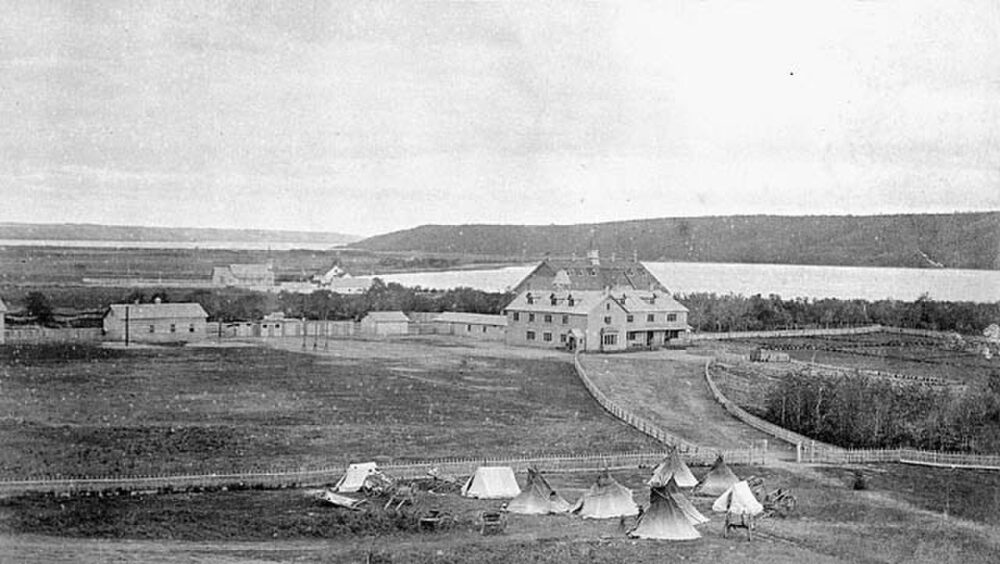

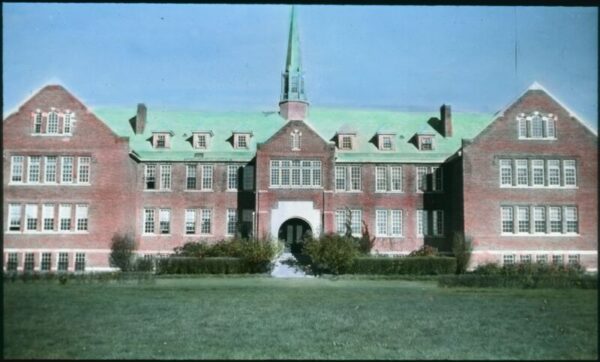

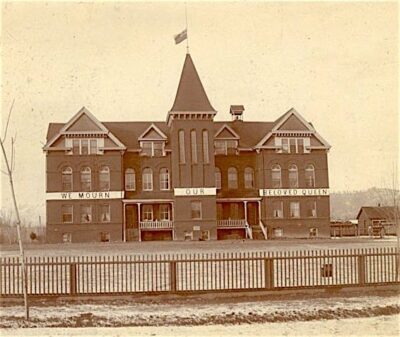

The Indian Residential Schools system, founded in 1879, was implemented with an objective to “civilize [or] Christianize” the Indigenous people – the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit (Milloy, 1999, p. xiii). This education system was operated through a church-state partnership. The Government funded the IRS, supervised the administration of the schools, and set the standards of care for the children who were “wards of the Indian Affairs Department (IAD)” (Milloy, 1999 p. xiii). The churches that operated the schools were Roman Catholic, Church of England (Anglican), United Church (Methodist), and Presbyterian Church. The policy of this education system was designed to move Indigenous communities from their ‘savage’ state to that of ‘civilization’, thus to make but one community in Canada. “The goal of the Residential School System,” said Sir John A. Macdonald, first Prime Minister in Canada, “was to assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the inhabitants of the Dominion.”[6] Therefore, the intention of replacing Indigenous culture and identity with Euro-Canada civilization was clearly stated. At the same time, some Government officials believed that children could not be easily civilized on reserve because the practice of Indigenous traditions and culture in their home and communities would slow down the process of assimilation. In order to educate and civilize the children properly, they must be separated from their families, said Hector Langevin, a federal cabinet minister then.

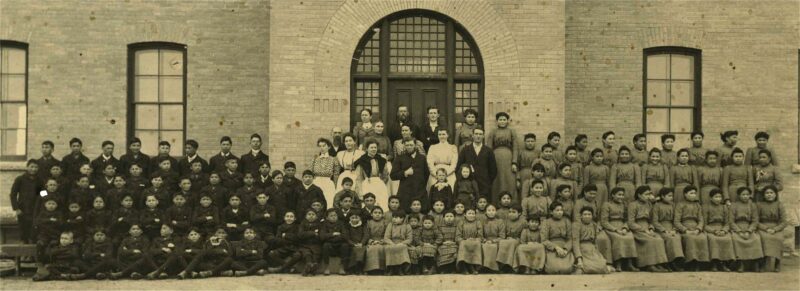

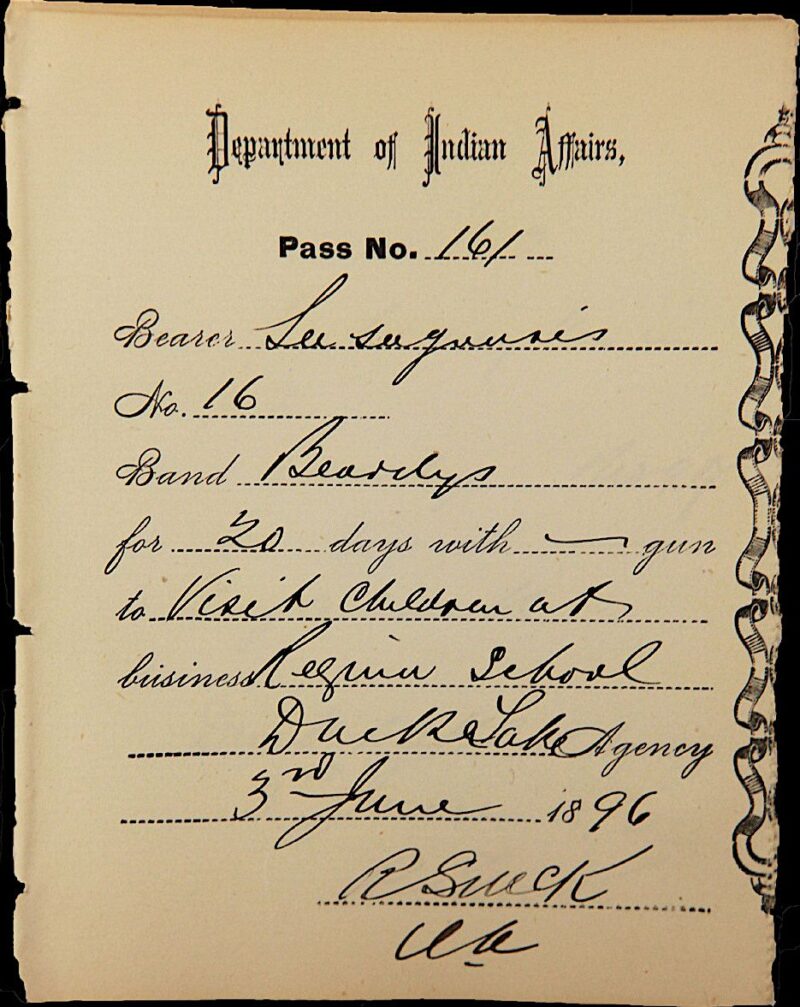

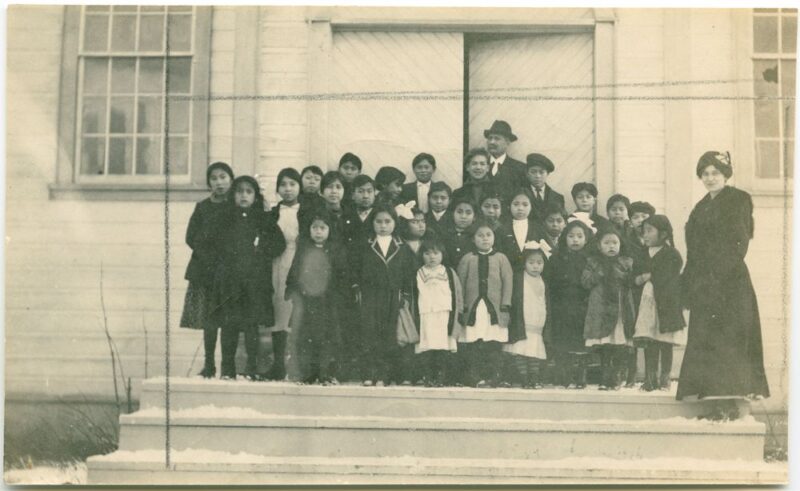

In 1883, the Government made it obligatory for Indigenous people to send their children from the ages of six to sixteen to the boarding schools in their region. These children would remain in the schools for education and industrial training for at least 10 years (Churchill, 2004, p.21). Right from the beginning, Indigenous parents did not want their children taken away from home and refused to send them to the residential schools despite the law. Church officials, too, found it difficult to convince parents to send their children to residential schools. Thus, in 1920, the Indian Act was amended to make school attendance compulsory. When Indigenous parents failed to send their children to residential school, a church official or an agent from the IAD, often accompanied by one or two Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers, would go to Indigenous homes and take the children away from their parents. Then they would be transported to the school, which was usually located far from their homes or communities (Churchill, 2004 p.18).

By the 1930s, there were over 70 residential schools operating in different parts of the country. In the 1940s, however, federal officials had concluded that the IRS system was both expensive and ineffective, and the schools were gradually closed down. As a result, the Government began to substantially increase the number of on-reserve day schools. In the 1950s, the Government entered into an agreement with provincial governments and local school boards to have Indigenous students educated in public schools, thus beginning a policy of integration. By the 1970s, the Government had succeeded in making provisions for approximately 60% of Indian students in public schools (Kirkness, 1999 p.29). The last federally administered residential school, the Gordon Residential School in Saskatchewan, was closed in 1998. Throughout the entire history, there were about 130 IRSs across the country; and more than 150,000 First Nations, Metis, and Inuit children had attended them. Today, approximately 80,000 IRS survivors are alive.[7]

The Reception and Assignments.

After Indigenous children were removed from their parents’ homes, they were sent to the IRS by trucks, canoes, or on foot depending on the availability of vehicles and the distance involved, usually many miles. Generally, the children stayed in the same school until they reached the age of 16. If their parents moved, their children would be transferred to another IRS in the district or region where their parents then resided. Some fortunate students were able to return home during the summer while many others remained in the school until they had completed their ten years of schooling.

As soon as they entered the school, stripping of their identities would begin. Their long hair was cut and deloused with chemicals such as alcohol, kerosene, coal oil, or a pesticide (Churchill, 2004 p.19; Sellars, 2013 p.32). The school administrators replaced their native names with Christian names and/or gave each child a number for easy identification. They took away their clothes and supplied them with European-style school uniforms. In the 1950s, some schools such as St. Joseph’s Mission in Williams Lake, British Columbia (BC) supplied the students with jeans and T-shirts.

After the ‘cleansing’ procedures, the children were assigned and sent to their dormitories. Boys and girls were housed in separate dormitories. Depending on the size of the boarding school, one dormitory usually accommodated 20 to 40 students. Each dormitory contained rows of single beds with thin mattresses and blankets. The beds were set about three feet apart from one another, just enough space for the students to kneel down to say their prayers before they retired at night. Bev Sellars, one of the survivors, describes the facilities of her dormitory in St. Joseph’s Mission as follows:

[We] shared one bathroom, which had only five or six toilet stalls and one showers room. The shower room had no stalls, just a bare shower head… We were required to shower with our underclothes on. After we had showered, we were given dry underclothes and had to go into a private toilet stall to change (Sellars, 2013, p. 30).

Sellars also gave evidence that the students were assigned to different tasks in school. She missed breakfast on the first day because she had to clean up the schoolyard after rising, tidying her bed, and freshening up. She was hungry but not allowed go in for breakfast until a nun had inspected the yard cleaned by her and six other girls. Throughout the years, students were assigned different kinds of chores. The girls who worked in the building would wash dishes, set tables for meals, wax floors, polish silver for the priests and the nuns, and tidy and dust the offices of church officials. Outside the building, the boys and some older girls did everything from planting and harvesting the gardens to cutting wood for heaters, cutting and hauling in hay, looking after livestock, mowing lawn, raking grasses and leaves, etc.

School Programs and Practices.

Many survivors claimed that they had a regimented weekday schedule. Below is a typical weekday timetable of the Qu’Appelle School, Saskatchewan, around 1885 (Milloy, 1999, p. 137):

Table 1. Typical Weekday Schedule

| Time of day | Activity |

| 5:30 a.m. | Rise |

| 6:00 | Chapel |

| 6:30 – 7:15 | Bed making, milking and pumping |

| 7:15 – 7:30 | Inspection to see children are clean and well |

| 7:30 | Breakfast |

| 7:30 – 8:00 | Fatigue [chores] for small boys |

| 8:00 | Trade boys at work |

| 9:00 – 12:00 | School, with a 15 minutes morning recess |

| 12:00 – 12:40 [noon] | Dinner |

| 12:40 – 2:00 p.m. | Recreation |

| 2:00 – 4:00 | School and trades for older pupils |

| 4:45 – 6:00 | Fatigues, sweeping, pumping |

| 6:00 – 6:10 | Preparing for supper |

| 6:10 – 6:40 | Supper |

| 6:40 – 8:00 | Recreation |

| 8:00 p.m. | Prayer and retire |

This timetable indicates that students were required to do chores in the school, which had a dairy farm. Essentially, all IRS were expected to be self-sufficient; thus many of them, if not all, had large acreage to grow vegetables and to raise cattle for meat and dairy products.

The IRS school programs were relatively identical. The teachers taught the 3Rs — reading, writing, and arithmetic in class — but focussed on vocational or industrial training for the students. Classes were usually large; and the teaching fell back on recitations, drills, and memorizations of the ‘right’ answers. Since the Government mandated English as the language of instruction, students were prohibited from speaking their Indigenous languages, a crucial step in the process of assimilation. If they were caught speaking their own language, they were punished. The mildest form of punishment for such an offence was writing lines. One former student in BC, who was caught speaking Shuswap, recalled that he was made to write 100 lines that he “will not speak Indian any more.” Other forms of punishments for speaking their native languages included strapping, hitting, and locking in cellars or dark rooms, which terrorized many students. An Indigenous girl said that she didn’t even know what yes and no meant when she first entered the school (Churchill, 2004, p. 22). She was so scared and could not say anything. Once she forgot the rule and spoke her own language. Unfortunately, she was caught and received several whippings after which she was made to kneel in a corner for half an hour. Then she was told that the Indigenous language was evil!

Some students and their siblings attended the same school but they were not encouraged, if not prohibited, to speak or interact with one another for fear they might continue using Indigenous languages and transmitting their Indigenous customs and traditions to one another. So, gradually they became strangers who hardly knew and/or understood one another. This enforcement affected the ability of the students to relate with one another in later life.

In vocational training, boys were taught menial tasks needed by farms, mills, and mines so as to prepare them for cheap labour jobs. Girls learned sewing, cooking, and laundry care so that they could become maids and household servants or work in commercial laundries and service industries such as waiters and cooks in restaurants (Churchill, 2004 p.vx). Quite often, students attended class part-time and spent the rest of the day working for the school. These kinds of involuntary and unpaid jobs were presented as practical training for the students, said Chief Robert Joseph. With so little time spent in class, most students had only reached grade five by the time they left school! (Barman, Hebert, & McCaskall, 1986 p.86).

As the timetable indicates, meals were supplied but the portions of food for students were meagre and the quality was less than nutritious. In 1904, the Reverend Sinclair, principal of Regina Industrial School, admitted that a regular school meal consisted of bread and drippings or boiled beef and potatoes (Churchill, 2004 p.30). But some food invoices showed that the school had ordered luxurious food items such as sardines, tongue, canned salmon, oysters, different varieties of canned fruits, icing sugar, etc. Why students were not given some of the food?

A grandmother who went through St. Joseph’s Mission in the early 1920s recalled that the students were given a piece of bread smeared with tallow [margarine] and mush [oatmeal] with no sugar or milk for breakfast. At lunch, they got broth with bits of toast floating around. The crumbs of toast were the breakfast leftovers from the nuns and priests. For supper, they got meat boiled together with potatoes. Once they got a roasted potato without butter or salt — but to them, it was a real treat (Sellars, 2013 p.59). At Christmas time, a boy in the Onion Lake Residential School, Saskatchewan, wrote to his father as follows:

I am always hungry. We only get two slices of bread and one plate of porridge. Seven children run away because [they were hungry]…We are treated like pigs; some of the boys eat cats and [raw] wheat … Some boys cried because they are hungry. Once, I cry too because I was very hungry (Milloy, 1999, p. 109).

In 1944, Dr. A. B. Simes, medical superintendent of the Qu’Appelle Indian Hospital, submitted a report to the IAD stating that “28% of the girls and 69% of the boys were underweight” in the Elkhorn School, Manitoba, an indication of starvation. Simes also discovered there was not enough milk, no potatoes or other vegetables on stock, and the children never received eggs. This occurrence was probably caused by insufficient funding from the Government and/ or the misuse, if not exploitation, of funds by school administrators (Churchill, 2004; Milloy, 1999[8]). Obviously, this school had failed being self-sufficient. However, the diets for some school staffs and administrators consisted of plenty of bread, good portions of meats [beef], vegetables, milk, and eggs but the children were given less than they deserved (Milloy, 1999 p.117).

Sellars, who went to St. Joseph’s Mission in the 1960s, stated that she could not eat the food in the school. She and some of the students used to wrap what they could not eat in napkins and then throw it into the garbage. Once, Junie Paul [a student] was caught throwing food into the garbage. A nun saw her and made her dig the food out of the garbage and eat it. Paul sat there crying and gagging, trying to get the food down. Often, instead of throwing out rotten food, one of the cooks used to mix it with soup for the next meal. Fortunately, not all the cooks in the Mission agreed with the food policy of serving substandard diet to the children; one was Pat Joyce. When there was food left in cooking pots, he allowed children to help themselves to it. Some students, however, would get corn flakes, toast, an orange, and juice for breakfast, a meal that they had longed for. This would only occur on the days when they were being confirmed or receiving their First Holy Communion (Sellars, 2013 p.58).

The typical timetable only shows the weekday schedule. What about the weekends? In some schools, Saturday was a clean-up day of the school building by students. The students would mop, wax and polish the floors of the school building including the dormitories, dust and wash windows, and change bed-sheets and pillowcases and take them to the laundry room. Later, students working in the laundry room would deliver clean linen and clothes to the dormitories for the occupants to make their beds and to keep their fresh clothes in the closet to be used in the coming week. Sunday was a day of outing if weather permitted. Some school might have a panic with roast wieners/sausages and buns, and students would have chances to play games such as volley ball, basket ball etc.

Many students, however, have positive memories of their IRS experiences and speak positively of the skills they acquired, the recreational and sporting activities, and friendships they made. They played volley ball, soccer, and hockey in recreation time and formed teams to compete with public school teams in tournaments. Some IRS included music or bands in their recreation programs. For example, the pipe band in St. Joseph’s Mission went to play at the Montreal Expo in 1967. Unfortunately, many of the tragedies and abuses occurred in the IRS had overridden the good deeds and intentions of the school staffs and administrators and some fond memories of the former students.

Incidents and Consequences.

Many children in the IRS did not see their parents and grandparents for many years, and parental visits were often discouraged and controlled. Virtually all of the children suffered acute loneliness and fear; they felt abandoned by their families who were in reality powerless to protect them. The isolation from their family, the strange environment, and the harsh treatments they received in boarding school caused many children cry themselves to sleep and wet in bed at night. The bed-wetter was often accused of being too lazy to go to the toilet and was strapped. At times, the bed-wetter was made to kneel down for hours after the beating. In St. Joseph’s Mission, the nuns, after beating the bed-wetter, made him/her hang out his/her wet bed-sheet to show other students that he/she had wetted the bed. This kind of incidents also gave other students to tease and laugh at the bed-wetter (Sellars, 2013 p.33). This was the kind of humiliation or embarrassment that students suffered. Charles Cline, a student of the Norway House School, Manitoba, ran away many times in his eight years at the school because he was strapped every time he wetted his bed. In the winter of 1907, Cline was whipped for wetting his bed as well as for stealing some clothes from the school supplies. He ran away again and suffered from frostbite; consequently, he lost six toes, three on each foot.

Many students learned to steal. William Brewer, a student of the File Hill School, Kamloops, BC, admitted that he and some students had stolen apples from barrels kept in the school attic. “They [the apples] were good. When you’re hungry, anything’s good,” said Brewer. These apples were for the school staff. When they were discovered stealing, they were strapped. Ralph Sandy, a former student echoed this sentiment: “In order to survive in that school we had to learn how to steal. If you didn’t steal…you starve.” (TRC, 2012, p.33) In the Sharing Circles at the National Event in Vancouver, two survivors, Dorothy Coyote and Agnes Edward, admitted that they had stolen wine from their schools. Both of them were caught and strapped, and Coyote was put on probation. A few hungry students even stole and ate the host from the church altars. Some older and bigger students lied and bullied the younger and smaller ones. For example: Annie Plume, at the age of five, went to St. Paul’s School, Alberta. Right from the start she was bullied by older children. Every time she complained to someone in authority she was sent to bed without any supper. She soon learned to keep quiet. In 1923, a boy in St. George School, BC, ran away because some older boys were using him to commit sodomy (Milloy, 1999 p 132)!

Besides Cline, many students attempted running away from the IRS. Unfortunately, some runaway students lost their lives. In 1902, Johnny Sticks found the dead body of his son, Duncan, lying on the snow about 75 yards from the road. Duncan, a student of the St. Joseph’s Mission, was only eight years old when he ran away. Sticks testified in court that he found “blood stains in the snow and blood marks on his son’s nose and forehead, [and the] left side of his face partially eaten by some animals” (Milloy, 1999, p. 142). Sticks took the body of his son home in a sleigh but he was upset that the school had not notified him of his son running away immediately. “He ran away from the Mission about one o’clock on Saturday and must have been dead for nearly two days when I found him” continued Stick in his testimony. Similarly, in January 1937, four boys who ran away from Lejac or Fraser Lake School, BC,[9] were frozen to death on the Fraser Lake about half a mile from their villages. The coroner examining the deaths criticized the school’s excessive corporal punishment and the failure to conduct an effective search.

Many school authorities and the IAD had been informed and criticized for excessive corporal punishment but such criticisms seemed to fall on deaf ears. In 1907, William Morris Graham, an inspector of Indian Agencies reported to IAD that Principal McWhinney of the Crowstand School[10], Saskatchewan, had tied the runaway boys behind a wagon and made them run from their home to the school, a distance of eight miles. He recommended that McWhinney be dismissed. J. D. McLean, the secretary of IAD, referred the matter to the Presbyterian Church. McWhinney admitted that he did tie the boys behind the wagon but the boys only walked [not ran] a considerable part of the way. Then he promised he would not adopt the same method of discipline in future. Thus, the matter was closed (Milloy, 1999 p.145). Again, in 1919, a runaway student from the Anglican Old Sun’s School, Alberta, was captured, shackled to a bed with his hands tied, and beaten with a horse quirt until his back was bleeding. The accused, P. H. Gentlemen, admitted to having used a whip and shackles. The case was brought to the attention of D. C. Scott, the Deputy Minister of Indian Affairs. Again, Graham recommended dismissal for Gentlemen. Scott turned to the church authority for advice. The general secretary of the Missionary Society responded that such corporal punishment was the norm! Gentlemen remained in the school.

The above are just two cases illustrating the brutality of corporal punishment in the IRS. Many schools applied similar punishments to discipline the children in the name of teaching obedience. Undoubtedly, these forms of harsh treatment created traumatic stress for them. The emotional turmoil within them had shaped their behaviours, attitudes, and outlooks in later life. Since they were raised in an environment without respect and trust but with terror and torment, they learned to become suspicious, disrespectful, defensive, cynical, aggressive, and ready to fight and resort to violence in any situation that seemed threatening to them. To vent their pent-up emotions, they adopted bullying and fighting with their schoolmates.

Incidents of sexual abuse had occurred in many IRS although the churches and Government preferred to deal with them quietly, but many victims wanted protection and safety. Unfortunately, no one was there to help them when the abuse took place. In a couple of instances, the community protested and, on one occasion, the victims stood up for themselves. In 1899, members of the St. Peter’s Band in Manitoba complained that the principal of the Rupert’s Land School had kissed a girl and beaten other students; the principal was dismissed. Fifteen years later a farm instructor of the Crowstand School had sexual intercourse with young girls in his room as well as in the dormitories; he was fired. At Fort Alexander, in the 1950s, younger boys were sent to a priest to wash their genitals. Ted Fontaine recalled that the practice ended when the boys grew bigger and threatened to hurt or kill the tormentor.

In the 1990s, the time had been reached for former students and their support groups to disclose this page of ugly history. They launched lawsuits against their predators. In 1993, Derrick Clarke, a former employee of the St. George’s Residential School, Lytton, BC, pleaded guilty to sexual abuse charges. In 1995, the RCMP initiated an investigation into all residential schools in BC. Following that, 14 charges were laid, and jail sentences imposed on eight former staff members of St. Joseph’s Mission, Williams Lake, Kuper Island, St. George’s School, Lytton, and the United Church School in Port Alberni, respectively. In many other instances, cases did not proceed because the alleged perpetrators had died or because, with the passage of time, Government lawyers concluded there was insufficient evidence (TRC, 2012).

The most notable prosecution of sexual offence was the case of Bishop Hubert O’Connor. He resigned as bishop of the diocese of Prince George, BC, when he first faced sex charges in 1991. He was convicted in 1996 of committing rape and indecent assault on two young Indigenous women when he was a priest in the 1960s. He maintained his innocence throughout the long court battle, arguing his accusers had consented to sex. He admitted to fathering a child who was placed for adoption. He was sentenced to 2½ years in prison. After serving six months in jail, he was released on $1,000 bail. The BC Court of Appeal later acquitted him of sexually assaulting a student at a Williams Lake residential school where he was principal. The rape charges were dropped after he apologized to his accuser in 1998 at a traditional native healing circle held at Alkali Lake, a small native village near Williams Lake (Hawthorn, 2007).

Meanwhile, Brother Glenn William Doughty and Father Harry McIntee were also convicted for sexual offenses. Doughty was a dormitory supervisor and a child care worker at St. Joseph’s Mission in Williams Lake and then on Kuper Island near Chemainus. In 1991, he was sentenced to four years for sexual abuse of four native boys at the residential school in Williams Lake when he was there in the 1960s. In June 1989, Father Harry McIntee pleaded guilty to sexual abuse of 17 native and white boys over a period of 25 years while he was at the Williams Lake residential school. He was sentenced to two years in jail plus three years’ probation (Hawthorn, 2007).

Continuing Negative Impacts.

Clearly, the history of the IRS system is marked by exploitation and abuse of children. Removing children from their homes without parental consent is inconceivable, and such removal had crippled the emotions of both parents and children. The parents felt guilty because many of them had gone through the system and were aware of the abuse that their children had to endure. They missed their children, yet the visitations to their children were controlled. In 1895, parents who had their children in the Qu’Appelle residential school set up tents in the school compound to wait for their turn to visit their children. As they felt helpless and powerless to protect their children, many parents used drugs and alcohol to ease their pain and numb their feelings of anxiety and worry. These uses often led to destructive alcoholism and substance abuse, stated Ruth Alfred, one of the survivors. A lot of alcohol and drug addictions, violence, and family breakdowns today are the continuation of the effects from residential schools, added Gertrude Pierre, another survivor. The evidence provided by these two survivors illustrates the detrimental effects of tragic legacies.

In the boarding schools, the children lived without parental care/love or guidance and often suffered from physical and emotional abuse as well as malnutrition. They were enslaved to child labour maintaining the school’s buildings, yards, gardens, and farms and were discouraged or prohibited to speak or contact their siblings even though they were attending the same school. Gradually, they became strangers to one another. Further, they were prevented from contacting their parents; letters from their parents and grandparents were often censored (Sellars, 2013 p.68). The silence of their parents led them to believe that their parents, grandparents, and communities had abandoned them! The prohibition of speaking Indigenous languages and the lack of opportunities to observe their ceremonial traditions had alienated them from their culture, hence “the dislocation and loss of [Indigenous] cultural heritage and language,” as Pierre put it. Also, the separation from their parents’ world had left many students poorly prepared to make their way in the dominant culture. Being away from their parents for long periods of time deprived them the opportunities of discovering and learning valuable parenting skills. Jacque Adams apologized to her children at the Sharing Circle[11] for not being able to be a [good] mother as expected and admitted that she had failed her siblings as a sister. The failure was probably caused by lack of communication skills. “The system has damaged the fibre of family,” she added.

Very few adults in the school administrations attempted to reach out and understand the feelings of loneliness and isolation of their students but just punished them harshly for any mishap and/or, in the adult’s eye, any disobedience or nonconformity. In reality, these children were emotionally disturbed. Many survivors claimed that they suffered from nightmares[12] and involuntarily wetted their beds. To escape from the austere environment in school, some students attempted suicide. In February 1920, nine boys in St. George’s School ate poisonous water hemlock in what some parents believed to be a response to the way students were being disciplined; eight boys recovered and one died (Milloy, 1999 p. 148). The suicide attempts had lingered in the minds of many survivors before they attended healing therapies and counselling. Even today, the suicide rate is high in some First Nations communities.[13]

Those who lost their lives by running away from school were not alone. On February 18, 2013, the Canadian Press posted that “At least 3,000 children, including four under the age of 10 found huddled together in frozen embrace, are now known to have died while they were attending Canada’s Indigenous residential schools, according to new unpublished research.” For decades starting in about 1910, tuberculosis was a consistent killer — in part because of widespread ignorance over how diseases were spread. “The [IRS] were a particular breeding ground for [tuberculosis],” said research manager Alex Maass. “Dormitories were incubation wards.” This indicates negligence of building managements and ignorance of the IAD and church authorities in regard to health problems of the students.

The experiences of sexual abuse have caused many victims to lose their self-esteem making them feel dirty and ugly, unlovable and unwanted. Consequently, many of these victims consumed drugs and alcohol to numb their feelings and to forget the past. As they became alcohol and drug addicts, some of them earned money through prostitution to support their habits. It is, indeed, pitiful and sad that the victims often had no one to turn for help or to rescue them when the abuse took place. This is especially truly when the perpetrators were the very people who held authority over every aspect of their lives as students. And in many cases, their parents either feared or respected the church officials who operated the schools and failed to show the victims the very much-needed support.

Reconciliation.

The tragic legacies cited above give evidences that many unresolved trauma suffered by former students has been passed on from generation to generation. Although the Prime Minister of Canada Mr. Stephen Harper, Pope Benedict XVI, and the churches had apologized, are they good enough to lessen the negative effects of the tragic legacies? A First Nation friend said, “What does an apology do?” Pointing at his heart he continued, “The hurt is still here. My mother has received compensation through the IRSSA but no amount of money could help her erase the past!” A true and honest admission! This statement draws attention to the great need for reconciliation, a significant process of spiritual cleansing and emotional healing through counselling and forgiving. The TRC acknowledges the need for healing and reconciliation and provides health supports through Health Canada for anyone who requires counselling.

The TRC’s conferences, seminars, workshops, and other related activities for the survivors and their families, communities, former IRS employees, religious groups, and government officials and/or representatives aim at reconciliation and bringing awareness and understanding of this page of Canadian history to Canadians as well as to the citizens of the world. Especially in the national events, opportunities are provided for the survivors to share their pains and hurts courageously, honestly, and truthfully with one another and for recognizing that they had transmitted their unresolved traumatic stress to their family members, especially to their children. In the Sharing Circle, many horrible stories were heard and many tears shed! But it was great to witness many supporters, especially family members, who accompanied the survivors to go on the stage and share their past. It was so comforting to witness the demonstrations of forgiveness among family members and renewal of life for them.

In some sexual abuse cases, the victims gained courage and renewal after they had attended healing circle ceremonies. Marilyn Belleau, an employee of St. Joseph’s Mission, was sexually abused when she was eighteen. In June 1998, Belleau, at the age of 51, attended the healing circle at Alkali Lake. She said, “I chose to participate in this healing circle to empower myself. I was able to confront him [O’Connor] with the hurts and pains he had caused me. I have had to live with this pain for over 30 years.” (“O’Connor appeal dropped after healing circle,” Vancouver Sun, June 18, 1998, p. B1).

The traditional healing circle gives victims and their families the chance to fully express their grievances and sorrow, and the perpetrators their confessions of faults and failings with no interruption to reach an understanding and forgiveness. Bishop of Prince George Gerry Wiesner, RCMP Staff-Sergeant Peter Eakins, native leader Wendy Grant-John, and BC and Government officials took part in the circle. Belleau and Ernie Quantz, BC assistant deputy attorney-general, led the ceremony. Speaking on behalf of the complainants and her sister-in-law, Belleau said holding the traditional healing circle was a big step that provided “a sense of freedom” for the Esketemc natives around Williams Lake, a good demonstration of spiritual healing.

Now the evidence shows that the ceremony of the healing circle is an approach in the reconciliation process, but reconciliation does not enable the participants to forget. However, once the freedom from strife is gained, remembering could help the participants find ways of protecting, guiding, and loving themselves and preventing similar unpleasant or horrible incidents from occurring again to themselves or others.

The support for one another could be seen in the court room as well. For example: The former chief of the Alkali Lake First Nation, Charlene Belleau, sat through Doughty’s first trial on sexual abuse charges. She helped the victims tell their stories. “To me, there’s some sense of relief that maybe Doughty’s days in court are not at an end and that he’ll be held accountable for whatever crimes he may have committed on children,” she added. When the victims returned to their community, she helped them to put their lives back together. Belleau, indeed, is a just and wonderful lady. Her endeavours are assisting the process of reconciliation.

The TRC also hired regional liaisons to provide a link between them and communities for the purpose of coordinating national and community events and public awareness. Therefore, the national events across the country are open to all Canadians who are encouraged to participate. In addition to reconciliation, these events aim at creating understanding and appreciation of Indigenous heritage and cultures. The excellent work of the TRC has gained support and acknowledgement from many ethnic communities, friends and associates of the Indigenous, political leaders, and VIPs. In 2008, the Right Honourable Michaelle Jean, former Governor General of Canada, called on all “Canadians — elders and youth, Aboriginal or not — to commit to reconciliation and breaking down the wall of indifference. This is not just a dream, it is a collective responsibility.”[14] In a way, this writing is a response to her call for reconciliation, an ongoing process to gain peace and understanding in our multicultural society.

Conclusion.

Although great efforts have been made in carrying on the reconciliation process, it appears that the Indigenous communities are still in need of healing because the rates of substance abuse, violence, crime, child apprehension, disease, and suicide are high. These alarming phenomena testify to the existence of tragic legacies. However, the continuing work and assistance from the different communities and support groups will help the wounded, the prejudiced, and the disadvantaged to find new ways life. Indeed, all Canadians must participate in the process of reconciliation to increase and enhance peace and harmony in our multicultural society.

Despite the disadvantages and the haunting of the distressful past, many Indigenous people have come a long way. Some have become great leaders in their communities and in the country. Today, at least four members of the First Nations and one member of the Inuit are Senators[15] in the Government. They were appointed to sit in the Senate by various prime ministers. Many have become lawyers who pledge to carry on the missions of gaining justice and rights for their people. There are also Indigenous people studying science and medicine. Senator Lillian E. Dyck graduated from the University of Saskatchewan as a doctor of neural medicine. Many become professors, scholars, poets, authors, artists, and painters. Their success and achievements are the pride of the Aboriginal people as well as that of Canada. In concluding, the author would like to share a poem, Survivor, by Ahite Ch’eh John Edward, the Grand Chief of the First Nations, to illustrate his strength and pride, which are present in many Indigenous people. Grand Chief Edward projected this poem on the screen while he spoke at the TRC National Event in Vancouver on September 19, 2013.

Survivor

I have survived

My dignity intact

I grow stronger

I have my drum

I will sing my songs

I have my language

I still speak my words

There is an ache in my heart

Fire in my eyes

I can forgive, but

I can forget

No bar will hold me down

My spirit soars

I am proud to be Indigenous.

*

周蔡小珊硕士 Lily Chow Siewsan, M.Ed, is Multicultural Director of New Pathways to Gold Society, BC and a Member of Canadian Chinese Historical Society of British Columbia. The New Pathways to Gold Society is a First Nations and non-First Nations organization with a mandate to promote reconciliation and economic development in British Columbia. “Tragic Legacies” is copyrighted © by Lily Chow Siewsan, December 2013. This paper was first presented May 9-10, 2014 at Tsinghua University, Beijing, in a session described as “Aboriginal and Minority Education Studies: Building Bridges between Higher Educational Institutions in Canada and China.” Editor’s note: Lily Chow’s book Blossoms in the Gold Mountains: Chinese Settlements in the Fraser Canyon and the Okanagan (Caitlin Press, 2018), was reviewed by Henry Yu in The Ormsby Review.

*

Sources cited:

Alex Maass, “At least 3,000 died in residential schools,” The Canadian Press, February 18, 2013

Barman, J., Yves, H., & McCaskall, D. (Eds.). (1986). Indian education in Canada (Vol. 1: The legacy). Vancouver: Nakota Institute/ UBC Press.

Churchill, W. (2004). Kill the Indian, save the man: The genocidal impact of American Indian residential schools. San Francisco: City Lights.

Hawthorn, T. (2007, July 27). Disgraced B.C. Bishop died of heart attack. Globe and Mail, p. 1.

Kirkness, J. V. (1999). “Aboriginal education in Canada: A retrospective and a prospective.” Journal of American Indian Education, 39:1, pp. 14-30.

Miller, J. R. (1996). Shingwauk’s vision: A history of the Indian residential schools. Toronto, University of Toronto Press.

Milloy, J. S. (1999). “A national crime”: The Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879 to 1986. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

“O’Connor appeal dropped after healing circle.” (1998, June 18). Vancouver Sun.

Sellars, B. (2013). They called me number one. Vancouver: Talonbooks.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, An Overview: Indian Residential Schools, Available from http/www.trc.ca

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2012). Canada, Aboriginal Peoples, and Residential Schools – They came for the children... Winnipeg, MB: Author. Available here.

*

Appendix 1. Apologies. In the 1980s, various members of Canadian society began to undertake a reassessment of the residential school experience. Starting in 1986, Canadian churches began to issue apologies for attempting to impose European culture and values on Indigenous people.

1986 – The United Church

1991 – The Catholic Missionary – Oblate of Mary Immaculate

1993 – The Anglican Church

1994 – The Presbyterian Church

2008 – The Right Honourable Mr. Stephen Harper, Prime Minister of Canada, on behalf of Canada

2009 – Pope Benedict XVI offered the Vatican Expression of Sorrow

Source: The TRC Display at the National Event in Vancouver, September, 2013

Appendix II. Residential Schools in Canada, 1931:

Abbreviations: Roman Catholic (RC), Church of England (CE), United Church (UC), Presbyterian (PR)

Yukon

Carcross (CR), St. Paul’s Hostel (CE)

British Columbia

Abousaht (UC), Alberni (UC), Alert Bay (CE), Cariboo (RC), Christie (RC), Coqualeetza (UC), Kamloops (RC), Kitimat (UC), Kootenay (RC), St. George’s (CE), Lejac (RC), Port Simpson (UC), Kuper Island (RC), St, Mary’s Mission (RC), Sechelt (RC), Squamish (RC)

Alberta

Blood (RC), Blue Quills (RC), Crowfoot (RC), Edmonton (UC), Ermineskins (RC), Holy Angels (RC), Lesser Slave Lake (CE), Morley (UC), Old Sun’s (CE), St. Albert (RC), St. Bernard (RC), St. Bruno (RC), St. Cyoruian, (CE), St. Paul’s (CE), Sacred Heart (RC), Sturgeon Lake (RC), Vermillion (RC), Wabasca (CE), Wabasca (RC)

Saskatchewan

Beauval (RC), Crowesses (RC), Duck Lake (RC), File Hills (UC), Gordon’s (CE), Guy (RC), Lac La Ronge (CE), Muscowequan (RC), Onion Lake (CE), Onion Lake (RC), Qu’Appelle (RC), Round Lake (UC), St. Philips (RC), Thunderchild (RC)

Manitoba

Bittle (PR), Brandon (UC), Cross Lake (RC), Elkhorn (CE), Fort Alexander (RC), MacKay (CE), Norway House (UC), Pine Creek (RC), Portage la Prairie (UC), Sandy Bay (RC)

Ontario

Albany Mission (RC), Cecilia Jeffrey (PR), Chapleau (CE), Fort Frances (RC), Fort William (RC), Kenora (RC), McIntosh (RC), Mohawk (CE), Moose Fort (CE), Mount Elgin (UC), Shingwauk Home (CE), Sioux Lookout (CE), Spanish (RC)

Nova Scotia

Shubenacadie (RC)

Northwest Territories

Aklavik (RC), Fort Resolution (RC), Hay River (CE), Providence Mission (RC)

Note: In Quebec Fort George (RC) and Fort George (CE) were opened before the Second World War and after the War Amos, Pointe Bleue, Sept-Iles and La Tuque were added

Source: J.S. Milloy, A National Crime, Appendix, 1999

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] Government of Canada, Canadian Heritage, National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

[2] This apology was broadcast in CBC and published in numerous newspapers such as the Globe and Mail, Vancouver Sun, etc., and that statement was printed and handed out to public at the TRC National Events in 2013

[3] The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) was established in 1991 to address many issues dealing with the historical relations between the Government and Indigenous people.

[4] The agreement provided for a payment to all former students who resided in federally supported residential schools, additional compensation for those who suffered sexual or serious physical abuses or other abuses, a contribution to the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, support for commemoration projects, the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the provision of mental health supports for all participants in settlement agreement initiatives – extracted from The Report of TRC in 2012 to the Parties of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

[5] Prior to 2014, the TRC had organized and held six national events in the following cities: Winnipeg (June 2010), Inuvik (June 2011), Atlantic (October 2011), Saskatoon (June 2012), Montreal (April 2013), and Vancouver (September 2013).

[6] As quoted in J. Milloy, A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System: 1879 to 1968, p. 6.

[7] An Overview: Indian Residential Schools, Publication of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

[8] Both books give extensive accounts of the funds provided for some IRS and food supplies and being consumed. As the writer was not able to secure the government documents at the time of writing, the stats are not included.

[9] The Lejac or Fraser Lake School opened in 1922. After the incident in the subsequent decade, parents wrote letters to the Government protesting the harsh conditions and often refused to re-enrol their children in the school. In 1969, the Government took responsibility for the administration of the school until 1976, the year when it was closed – from TRC’s display in the National Event, Vancouver, September 2013.

[10] The Crowstand IRS in Kamsack, Saskatchewan opened in 1888 and closed in 1913.

[11] TRC’s National Event in Vancouver, September 20, 2013.

[12] Julia Harris at the Sharing Circle of TRC’s National Event, Vancouver, September 19, 2013

[13] Information from a Buddhist Monk, in Lytton, BC, 2010

[14] Her Honour made the statement at the National Event in 2008.

[15] The Indigenous senators are Charlie Watt (Inuit), Nick G. Sibbeston (First Nations) Lillian Eva Dyck (First Nations), Sandra Lovelace Nicholas (First Nations), and Patrick Brazeau (First Nations).