1196 Minus 65° F on Borden Island

Flying to Extremes: Memories of a Northern Bush Pilot

by Dominique Prinet

Surrey: Hancock House, 2021

$19.95 / 9780888397553

Reviewed by Heather Longworth Sjoblom

*

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain. I regret to have to report that our plane is completely covered in ice and we are inexorably descending toward the tundra. In 10 minutes, we’ll hit the ground at cruising speed. Please ensure that your seat belts are fastened, say your prayers and wish your neighbours luck.”

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain. I regret to have to report that our plane is completely covered in ice and we are inexorably descending toward the tundra. In 10 minutes, we’ll hit the ground at cruising speed. Please ensure that your seat belts are fastened, say your prayers and wish your neighbours luck.”

This was the message that bush plane pilot Dominique Prinet thought of passing around to his passengers as their plane slowly fell from the sky in July 1969. He didn’t know where they were in the arctic. They’d been trapped above the clouds until the ambient temperature dropped, the plane and the propeller were gradually covered in ice, and they began to lose altitude. Most of his passengers were asleep and those that were awake had no idea how dire the situation was, as they couldn’t hear Prinet’s unanswered mayday calls over the roar of the engine. Rather than send this message, Prinet chose to keep the crisis secret because any movement in the cabin would upset the plane’s balance. They fell through the clouds and, miraculously, hit the edge of a small lake with zero visibility, still enveloped in thick fog.

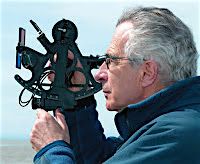

Dominique Prinet records his adventures as a bush pilot in the Northwest Territories (NWT) from 1967 to 1971 in Flying to Extremes: Memories of a Northern Bush Pilot. As he was growing up in France, Prinet’s family wanted him to study at the École Normale, a top French University. Prinet failed the entrance exam. He then decided to obtain his professional pilot’s licence and became a flight instructor. With his life in disarray, he moved to British Columbia to work as a logger. When the logging camp closed due to snow, he became a pilot and flight instructor and was later offered a job in the NWT. He wrote down many of his experiences and published them in the French aviation magazine Aviasport. These stories, translated into English, are now gathered together in this book, along with beautiful colour photographs of the arctic.

Being a bush pilot in the NWT in the late 1960s was a challenge. Not every lake was mapped and those that were blended into the scenery in the winter when their frozen surfaces were blanketed with snow. Pilots flew in extremely cold temperatures in the dark winter or around the clock in the summer when the sun barely set. Flying in all seasons meant learning to land on wheels, floats, and skis. In the summer, pilots lacked sleep and there weren’t stringent transportation laws in place to limit the number of hours in a shift. Prinet recalled, “We would try to catch a nap of 20 minutes here and there, perhaps 45 minutes during a stopover or while on a flight, when a mechanic was refuelling or when we could hand over control to a passenger.”

In winter, pilots had to use blow pots to warm the oil tank and engine. It could take over an hour for the oil to thaw. The “most atrocious” winter flight Prinet recalls is a 1969 oil exploration flight to Borden Island. Temperatures dropped as low as -65° F and most of the flight took place in near total darkness. Prinet was so physically and mentally drained he risked some crazy take offs and landings.

Pilots were paid three to five cents a mile (depending on the type of aircraft), “measured in a straight line from the departure point to the destination.” Payment was made only if the flight was completed so, if the pilot had flown five hours and been unable to land due to weather, he wasn’t compensated. Nor was he paid for detours or days spent waiting for the weather to improve.

In Prinet’s experience, “pilots were paid not to fly planes, which anyone could do, but to worry intensely about the ghastly dramas that loomed and, in most cases, accumulated quickly.” Throughout these stories, Prinet maintains an outward appearance of calm and confidence for his passengers, despite the desperate circumstances he finds himself in. He is able to find a silver lining in these challenging situations, noting “Perhaps courage is simply the ability to see the absurdity of a situation before it unfolds, finding humour in it and remaining calm.”

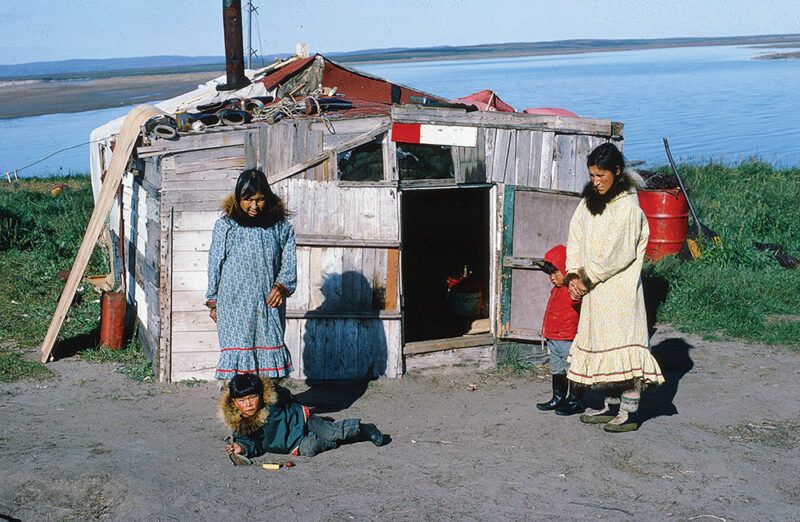

In addition to the aviation tales, this book gives a snapshot of Yellowknife in the late 1960s after it became the capital of the NWT. It also provides a glimpse into the lives of trappers, prospectors, and the Inuit communities who were served by these aircraft.

Prinet’s captivating writing, sense of humour, and unique experiences make this book a fantastic armchair adventure. When I visited Yellowknife a few years ago, I climbed the Bush Pilot’s Monument, which was erected there in 1967. Reading this book helps bring to life the risks that these pilots took, as well as their courage and dedication to serving people and communities in the north.

*

Heather Longworth Sjoblom is the manager and curator of the Fort St. John North Peace Museum. She has a BA (Honours) in history from Acadia University, an MA in history from the University of Victoria, and a Post-Graduate Certificate in Museum Management and Curatorship from Fleming College. As an environmental historian, Heather loves researching relationships between people and nature and working them into museum exhibits and programs. She also enjoys gardening, hiking, travelling, and spending time with her husband and son. Editor’s note: Heather Longworth Sjoblom has also reviewed books by Amy Wilson, Donna Kane, and Lily Gontard & Mark Kelly for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster