1177 Paint those final portraits

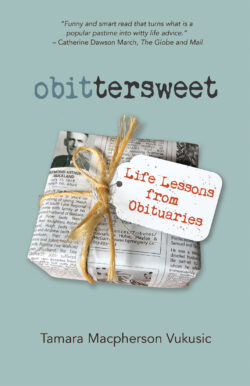

obittersweet: Life Lessons from Obituaries

by Tamara Macpherson Vukusic

Oakville, ON: Mosaic Press, 2020

$24.95 / 9781771615280

Reviewed by Carol Matthews

*

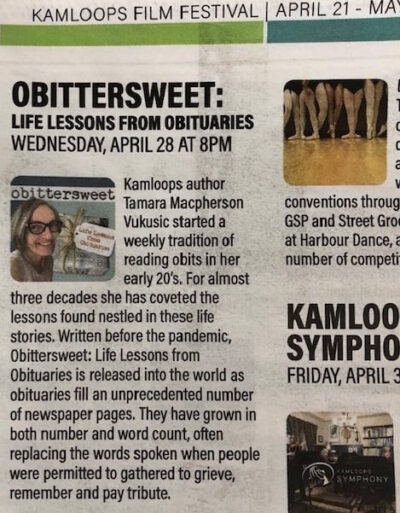

As a long-time reader of obituaries, I was delighted to receive a copy of Tamara Macpherson Vukusic’s collection of essays which is aptly titled obittersweet. Describing her Sunday morning ritual “with coffee in one hand and the obituaries in the other,” she asks “Why obituaries?” and explains that, for her, this ritual began when she worked as a communications officer for a Veterans’ Health Centre, seeking out details of the lives of people with whom she’d previously worked.

As a long-time reader of obituaries, I was delighted to receive a copy of Tamara Macpherson Vukusic’s collection of essays which is aptly titled obittersweet. Describing her Sunday morning ritual “with coffee in one hand and the obituaries in the other,” she asks “Why obituaries?” and explains that, for her, this ritual began when she worked as a communications officer for a Veterans’ Health Centre, seeking out details of the lives of people with whom she’d previously worked.

It’s a great idea for a book because, after all, aren’t a great many of us are regular readers of obituary columns? Some of us read obituaries to see if anyone they know has died. For some, it’s because of an interest in the lengths of the lives lived, noting that some weeks all the deaths are of very old people whereas at other times the column consists, shockingly, of people younger than oneself. And for many it can be a fascination with the way obituaries can capture the essence of a person’s life. I’ve heard that, after the front page, the obituaries are the most frequently read section in a newspaper. Like many, I enjoy reading them because they conjure up a portrait of a person that would not be present at any other time.

Obituaries recount people’s whole lives, often seemingly ordinary ones, and summarize their relationships, the work they did, the obstacles they encountered and the ways in which they overcame. As well, ideally, it shows what made them unique. Even in a very short obituary we may get a sense of what was distinctive about a person: quirks, loves and pet peeves. As Vukusic notes, an economy of words — nine or ten or even fewer — can help to distil the real essence of a person: “Thanks for the firm hand; thanks for letting go,” or “He patiently acted as the family Google to the end.”

The 120 “micro-biographies” in this collection are cleverly organized, each one being followed by additional facts, and sometimes the author’s fancies, that expand and embellish the story as she connects it with her own life experience. Each one concludes with a question that encourages readers to think more deeply about their own lives. Vukusic is a thorough journalist, and the final pages give a full list of obituary credits and the various sources consulted, testifying to her extensive research.

The essays are divided into monthly sections, and the calendar can serve as a guide to the year. The January section begins with an admonishment:

This year, rather than crafting a New Year’s resolution, consider reflecting on what you already do that is worth celebrating. Resolve to live your life in a way that, when you are gone, people notice something unique and precious missing.

I don’t generally enjoy self-help books, but Vukusic uses the lessons she gleans from her study of obituaries to prompt some really helpful reflection that could help readers to become better citizens who make important contributions to those around them. Her questions lead us to explore how we might endure difficulties, create a life that that satisfies our deepest desires, and perhaps encourages others to make positive changes. Following the recollections of a man who at the age of 40 left his career as a lawyer to become a teacher whose “genuine passion” for his work was a life-changing inspiration for his students, the question asked is, Regardless of your age, how can you craft a life that allows you to engage your passions? Who will thank you for it?

There’s the story of a woman who, because of multiple sclerosis, spent years in a wheelchair during which time she acquired skills in mouth painting and used her voice-activated computer to recruit volunteers for a variety of community events. Vukusic’s question to us is, What personal challenges can you reframe to enable others to see possibility in adversity? And there’s also the obituary of a women suffering from undiagnosed dementia whose hallucinations and paranoia “crept into her life like a bad neighbour,” yet was able to love life and its precious moments in the midst of trauma and chaos. The question at the end of this story is, What joy can you find in the midst of chaos? How do you find it?

If I have one quibble with this book it’s that it leans rather heavily on the sweet versus the bitter. That’s not surprising, given that obituaries tend to be tributes, not denunciations, and it’s heartening to read of the long and happy marriages and the endurance, resilience and generosity of so many. However, Vikusic’s imagination sometimes leads her to indulge in sentimentality as when she wonders “Did June bury her head in the back of his neck and breath him in?” and “Can you picture them giddy with excitement sitting on the train as the shrill whistle announced the start of their journey together?”

At the end of the book, Vukusic proposes while reading obituaries we might imagine that, instead of the face of a stranger, we see our black and white photo staring at us with a short summation of our own life. It could make one recall the message in the 15th century morality play Everyman: “O Death, thou comest when I had thee least in mind.” Death can happen at any time and it behooves us to consider that, throughout our lives, we’re gathering material for that final portrait.

Despite its sombre topic, obittersweet is a cheerful and ultimately uplifting book. If you’re looking for a gift to give to a friend who is depressed or at a stuck place in her life, this may be the perfect choice.

*

Carol Matthews has worked as a social worker, as Executive Director of Nanaimo Family Life and as instructor and Dean of Human Services and Community Education at Malaspina University-College (now VIU). She has published a collection of short stories (Incidental Music, from Oolichan Books) and four works of non-fiction. Her short stories and reviews have appeared in literary journals such as Room, The New Quarterly, Grain, Prism, Malahat Review and Event.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1177 Paint those final portraits”