1131 Surrey Up!

Desire Path

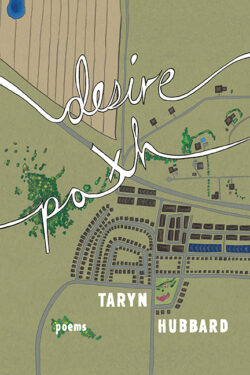

by Taryn Hubbard

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2020

$16.95 / 9781772012637

Reviewed by Michael Turner

*

The relationship of poetry and place is an age-old fascination that figured prominently in the self-conscious development of a modern North American literature. Long before his poem “This Is Just to Say” (1934) became a social media cat toy, William Carlos Williams chose Paterson, New Jersey — one of the first planned industrial sites in the United States — to fashion a poem that would distinguish the American experience in language (vernacular) and composition (mosaic) from the terminal ennui of T.S. Eliot’s post-WWI “The Waste Land” (1922). The result, his multi-volume, multi-genre epic Paterson (1946-1958), is an excitation of place that inspired the New American poets who followed, as well as their followers, including the 1960s TISH poet/editors of Vancouver. This invocation of place as muse in B.C. poetry continues today in the work of younger poets Jordan Abel, Phinder Dulai, Sachiko Murakami and Cecily Nicholson, and most recently in Taryn Hubbard’s debut collection Desire Path (2020).

The relationship of poetry and place is an age-old fascination that figured prominently in the self-conscious development of a modern North American literature. Long before his poem “This Is Just to Say” (1934) became a social media cat toy, William Carlos Williams chose Paterson, New Jersey — one of the first planned industrial sites in the United States — to fashion a poem that would distinguish the American experience in language (vernacular) and composition (mosaic) from the terminal ennui of T.S. Eliot’s post-WWI “The Waste Land” (1922). The result, his multi-volume, multi-genre epic Paterson (1946-1958), is an excitation of place that inspired the New American poets who followed, as well as their followers, including the 1960s TISH poet/editors of Vancouver. This invocation of place as muse in B.C. poetry continues today in the work of younger poets Jordan Abel, Phinder Dulai, Sachiko Murakami and Cecily Nicholson, and most recently in Taryn Hubbard’s debut collection Desire Path (2020).

At 80 pages, Desire Path is a refreshingly spare, unchaptered gathering of poems that detail what it can mean to grow up in the Lower Mainland’s increasingly molten Fraser Valley and, once formed, return there (if not remain there) as a guide to past, present and future conceptions. That these conceptions were developed along Time’s chronological pathway is a condition of one’s ordered and brutal youth; that their poems should often manifest in temporal palimpsests, conflating past and future with, among other contrasting states, desire and indifference, pits the lyric poet against the narrative historian. Yet in Hubbard’s hands, the poem can accommodate the influence — and interest — of both.

Those unfamiliar with the Fraser Valley will not have to read too far into Desire Path to recognize its often overlapping composition of agricultural farmlands, dilapidated town sites and suddenly concrete “city centres” as endemic to the North American suburban experience. As with Time, Space too is given in relative measures. In the opening five-part long poem “Heirloom”, we learn that the poet’s “I” was “born across from the first/ McDonald’s in Canada,” which Google tells us was in Richmond, “outside of Vancouver,” in 1967. As well as a visual signpost, this MacDonald’s was an audio presence, an order-taking Morpheus whom the young subject fell asleep listening to: “the muffled sounds/ of the drive-thru speaker” a parenthetic device where the subject’s first words (“upsized, waxy/ drowned// in a syrup that stayed with me”) were caught and held — “until I lost that desire.”

Time begets Space at the opening of the second section:

One year goes by

then another, another

until my time is stacked

high around, and I look

to see I’ve formed a line

Hubbard’s “stacked” time parallels the increasingly swift transformation of the suburban-to-exurban landscape from low-rise town sites and their pawnshop-anchored mini-malls (hello Whalley) to one of a number of high-rise city centres that, with their Starbucks and gangsters, have come to characterize the Valley’s largest municipalities. Six lines later, she writes:

though one thing I’ll reframe,

from the start, is

the fact I’m working

doesn’t mean I’m bored.

The fact I’m making plans,

cutting corners,

indicates that this “making” and “cutting” — and later “severing” (“feet”), “swimming” (“for/ retweets”), “cracking” (“dreams”) and “striving” (“toward an unknown future”) — are part of the subject’s job description, be that a day job or the job that occupies all poets, 24/7. When gathered together, these verb/gestures contribute not only to the writing of poems and the wages required to underwrite them, but “means only I’m trying.// I am trying/ and that’s my worry.”

The third section of “Heirloom” recalls, in twelve lines, the subject reading a clipping from a community newspaper advertising a house for sale, what turns out to be her family’s second home — billed as “Grandma’s Country Charmer” — in the municipality of Surrey. Lines give way to paragraphs in the fourth section, where the subject tells of living in this house, which, like her former Richmond home, is next to a drive-thru, only this time it is not a McDonald’s but a family-owned operation seeking to emulate its success (they are “trying” too). The passage from the detached prose lines of the previous section to the paragraphic exposition of the following section suggests the “development” of the subject from lyric pastoral child to narrative epic adult, while the fifth and final section is a brief one that has the subject graduated from childhood and standing at the door, baggage in hand:

The path forward begins with a reference to what was left behind.

Or something.

And so the subject goes, into the grown world, on the “path” that is her “line,” haunted by a lost “desire,” always “trying,” in a state of “worry.” Like the suburban landscape, the formed subject bears recognizable characteristics, symptoms of modernity’s malaise, a modernity that gave us these suburbs in the first place. Same with the poem’s ostensibly indifferent, grungeworthy concluding line — “Or something.” But what is that “something” if it isn’t nothing? More poems, of course. Not the promise of more, but that there will be more.

Apart from the long poem “Attempts” (in which the subject’s own body provides the world in which her baby daughter comes to term) and a recurring four-part sequence entitled “Repeat”, the remaining poems are generally limited to a single page and range from language-compressed lyric poems to prose paragraphs. Together, these poems achieve a choral effect, larger than the sum of their parts, though there are number of stand-alone, stand-out works. Among them is “Wayfinding”, with its reminder of how suburbs are designed for cars first, people second: “from a form/ that grew only/ with the idea of/ car & home.” Another is “Dear 230B”, where

outside that one night

we swore pop was gun-

shot but action

movies rise though

your ceiling, neighbour, the

end of the universe

Strangely, and perhaps in resistance to the ordered events of the book’s “Contents” pages, the final poem is both untitled and unlisted, a hidden track that, like Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow” (1923), speaks wonderfully to the recovery of that which had been claimed by Nature, yet in its decay bears fruit:

I’ll call to tell the rust I’m growing you is beautiful

and blooming on the busted spokes

of the shopping cart I untangled

from the blackberry bush overtaking the ditch.

*

Michael Turner is a writer of variegated ancestry (Scottish/ German/ Irish, mat.; English/ Japanese/ Russian, pat.) born, raised and living on unceded Coast Salish territory. He works in narrative and lyric forms, both singularly, as a writer of fiction (American Whiskey Bar, The Pornographer’s Poem, 8×10), poetry (Hard Core Logo, Kingsway, 9×11), criticism and music, and collaboratively, with artists such as Stan Douglas (screenplays), Geoffrey Farmer (public art installations) and Fishbone, Dream Warriors, Kinnie Starr and Andrea Young (songs). His work has been described as intertextual, with an emphasis on “a detailed and purposeful examination of ordinary things” (Wikipedia). He holds a BA (Anthropology) from UVic and an MFA (Interdisciplinary Studies) from UBC Okanagan. Currently he is an Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies and Graduate Studies, Ontario College of Art & Design University and a workshop leader at Mobil Art School, Vancouver. Editor’s note: Michael Turner has also reviewed books by Jen Sookfong Lee, Isabella Wang and Sachiko Murakami for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1131 Surrey Up!”

This book has been a long time coming. How wonderful to know that it, like Taryn, has truly arrived.