1128 Stanley Park reflections

ESSAY: Stanley Park: The Mirror and the Mask

by Jordan Johnston

*

Stanley Park is a mirror that reflects the desires of those who look in it.

Stanley Park is a mirror that reflects the desires of those who look in it.

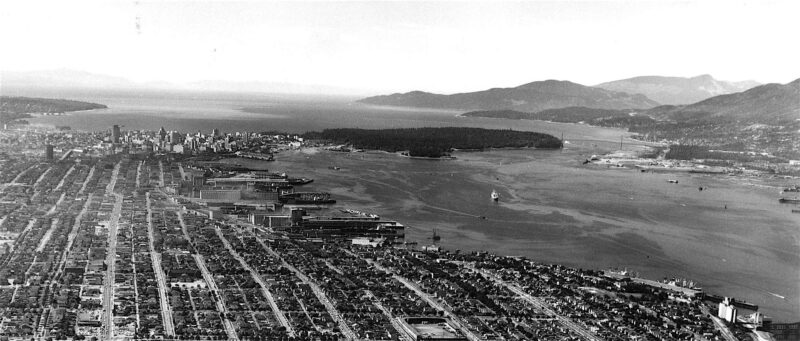

On a map, this bright green peninsula stands apart from the city centre, as if held at arm’s length. Vancouver, like any other city, has poverty, and crime, and pollution. But it also has the park, and the gentle mysticism that it inspires, and it is to the park that the averted eyes of its residents turn.

Only two years younger than the city, Stanley Park is one of its most identifiable landmarks. Since it was founded in 1888, the park has been embraced by Vancouverites as a source of pride, a place to show off to visiting relatives, a treasure to be guarded. Because citizens have identified so strongly with the park over the years, it has grown into a microcosm of the city. It is packed with landmarks and monuments — a rose garden, the prow of a Japanese ship, totem poles, graves and a cenotaph, stages where Shakespeare is performed and fields on which cricket is played – that exemplify the diversity of its users.

The park shows a different face to each visitor. Many regard it as a natural preserve or as an exercise facility. Some see a potential home among its trees; others, a home that was taken away. Still others, particularly in the past, have seen their beliefs about social class, mastery over nature or racial superiority reflected back to them here.

As the desires of those who visit this peninsula have changed over time, the land has been altered to reflect them. Its forests have been cut down, and then replanted. It has been fashioned and refashioned into a succession of images — shantytown, exclusive retreat, virgin forest, playground — each designed to please a different audience. Today’s Stanley Park is filled with reminders of these previous versions of itself. In examining them, we can glimpse the faces of those who looked in the mirror before we did.

*

Early on a chilly morning in November, I left my car near the edge of Stanley Park and crossed over its threshold on foot. There was frost on the ground and a biting wind was blowing off the water, but as the brilliant greenery surrounded me, I was comforted — as most visitors are — by the sensation that I was entering a special place. That is the mythical power that the park holds over us.

The frozen ground crunched underfoot. I pushed aside fir boughs, and was surrounded by their evergreen perfume. A grey squirrel ran across my path, then chittered at me from the safety of a high branch. My goal in visiting that morning was to see the site of the village of Xwayxway, which long stood in the place now occupied by the Lumbermen’s Arch.

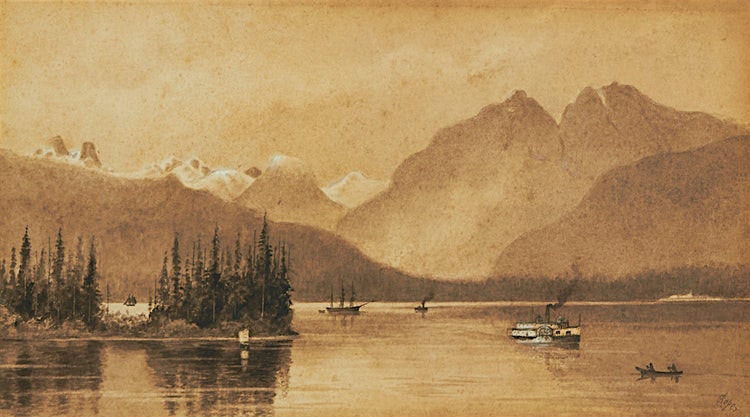

For millennia, Xwayxway (pronounced whoi-whoi) was used by the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples as a seasonal residence. There, they collected clams and seaweed, harvested cedar, and hosted potlatches. When George Vancouver arrived by ship at Xwayxway in 1792, he received an enthusiastic welcome. About fifty locals paddled out in canoes, presented him with gifts of cooked smelt, and traded with his crew. He described them as friendly and well-intentioned, saying they “conducted themselves with the greatest decorum and civility.”

Archaeologists have found evidence of habitation at Xwayxway from at least 3200 years ago. Elders interviewed in the nineteenth century said that hundreds or thousands of people had been living there for as far back as anyone could remember. The Coast Salish people will tell you that they have always been here. When the world was young, the Great Spirit turned a wolf into the first Tsleil Waututh man, and charged him with caring for all living things. When a flood covered the world with water, Mount Baker was the place where Squamish people first stepped out of a canoe and onto land. In those early days, the Transformers changed a virtuous new father into the place now known as Siwash Rock, and immortalized two daughters who brokered peace between warring nations by turning them into the twin mountain peaks called The Sisters (now commonly known as The Lions). Many of the physical features that can be seen from Xwayxway are tied to stories, which you can be sure were told and retold there.

There is a story behind the name of the village, too. It was the place where a mask arrived from the Spirit World, introducing a new song and ceremony to the Coast Salish people. Xwayxway became an important place for celebrations, including potlatches held long after they had been banned by the Canadian government.

But less than a century after George Vancouver arrived there, the village lay mostly abandoned. Its residents had been killed by smallpox, drawn away in search of work, or moved to reserves. Eventually, only the name remained. In Henqimenem, the Coast Salish language, Xwayxway means “the place of the mask.” Or alternately, “the place for making masks.”

*

The day I visited, many people in the park were wearing masks. The Covid-19 pandemic was on everyone’s mind, and most of the dog-walkers and strollers that I passed were wearing one. Despite the covered faces, it was easy to see that everyone was glad to stretch their legs. I savoured lungfuls of forest air while my own legs settled into a ground-eating rhythm.

As the morning passed, and the day warmed up, I met more and more people. The path I was on crossed Stanley Park Drive and I joined the pilgrimage route on the seawall. Cars began to pass in ones and twos, filled with couples out for a quiet drive, or with families looking to explore the park’s vast interior. Like the friendly passers-by, the cars seemed out of place. For many months, they had been absent from the park.

In April, 2020, the Vancouver Parks Board — an elected body that manages all of the city’s green spaces — decided to ban vehicles from the park. It was hoping to prevent the dangerous overcrowding that had occurred during the early days of the pandemic. A prolonged and emotional debate preceded this decision, and it was revisited when the ban was lifted. “Who does the park belong to?” was a common refrain among speakers at the public hearings. Some argued that cars were the only way for residents from the East side and from the suburbs to reach the city’s largest patch of green space. And others argued that a park that is too crowded isn’t really a park at all.

*

Over a century ago, the Parks Board presided over a similarly polarized debate. In the early nineteen hundreds, the level of access a person had to Stanley Park reflected their social class. Most of the park was difficult to reach from the city. Only those few who were wealthy enough to own a car, or to hire one, were able to get easily to its most remote areas. Everyone else had to take a streetcar to the foot of Georgia Street, and then walk. As a result, the areas of the park next to the city were very crowded, while those in the interior were quiet. In an effort to improve accessibility, the Parks Board considered a proposal in 1910 to build a tramway into the park’s interior. Debate over this proposal pitted two differing visions of the park against each other: was it useful land that should be open to everyone, or a fragile treasure in need of protection?

Spokespeople for Vancouver’s growing, and increasingly influential, working class supported the proposal: it provided much-needed green space for workers. They viewed Stanley Park’s acres of forest as an untapped resource which should be made available — for rest and for recreation — to all. The park should not be “a holy retreat, but should be a practical breathing spot,” said one spokesperson.

Residents of the West End, at that time the most affluent neighbourhood in the city, were largely against the proposal. They argued that it was the park’s separation from the city that made it such a special place: that its charm and fascination lay in the fact that it was so difficult to penetrate. Overcrowding and overuse brought on by tram access, they argued, would destroy the park’s sanctity.

A series of referenda were held on the proposal from 1910 to 1913, with the results playing out roughly along class lines. The proposal won marginal support from each area of the city except the West End, where it was defeated roundly enough to decide the result. Eventually, the proposal was abandoned.

The modern layout of Stanley Park reflects the visions espoused by those on both sides of the debate. It contains places to gather for play — still concentrated where the park and the city centre meet — and quiet areas of thick forest. Even now, no public transportation goes past the entrance of the park. Only the growth in vehicle ownership has opened its interior to the general population. And the recent uproar over the vehicle ban reveals that those outside the West End want to hold on to their hard-won access to the park.

*

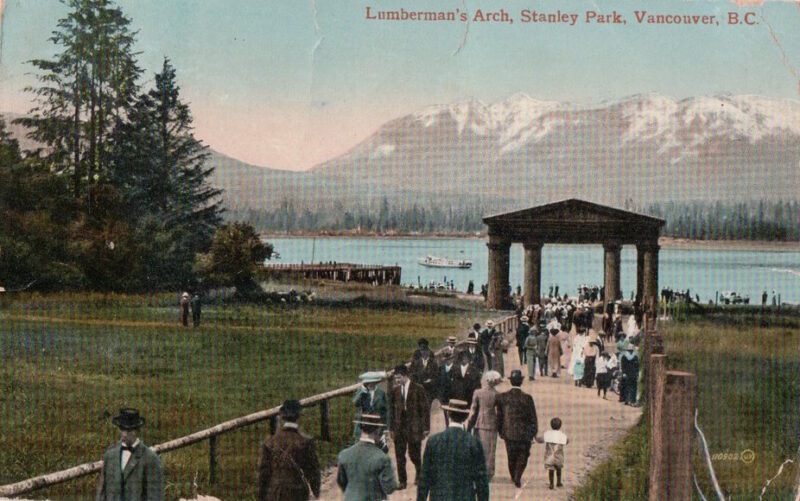

Driving or cycling around Stanley Park Drive is a wonderful experience. Many of the park’s most popular attractions are accessible from this perimeter road, and the views across the water are breathtaking. The road is always bordered on at least one side by a wall of forest, and even inside a car it can feel at times like you have left the city. When you reach Lumbermen’s Arch, though, this pattern is broken. A yawning chasm opens in the forest.

When you arrive there by trail, the break is even more apparent. On that November morning, I emerged from the forest to see a great green lawn, sloping down toward the sea, with the angled logs of Lumbermen’s Arch standing just this side of the glimmering ocean. To my right was an aquarium, to my left a snack bar. The hummocky lawn looked like it was plastered over a scar.

I followed the walkway toward the arch, stumbling occasionally. My eyes were fastened on the North Shore mountains, their fresh coating of snow reflecting the pink-hued morning light. The light was duplicated again on the smooth surface of the sea, dazzling my eyes twice over. The effect was broken when the rough-hewn logs of Lumbermen’s Arch obstructed my view.

The Arch was originally constructed at a downtown intersection, by a group of lumber magnates, in order to commemorate a 1912 visit by the Governor General. Later that year, it was floated across Coal Harbour to the park. Since then, it has been rebuilt twice. The current structure is a hefty cedar log inclined against the inverted V made by two smaller ones.

It stands on the spot once occupied by the village of Xwayxway. The village’s remains give shape to the grassy hillocks in the clearing. When it was razed, the space created became a convenient place to situate this monument to the timber industry.

*

Vancouver’s nineteenth century British settlers were part of an empire that relished its mastery over nature and superiority over other cultures. The land soon reflected these attitudes. The now-scenic peninsula was a denuded landscape then, cleared of trees and dotted with shacks housing non-British labourers.

The high quality, easily accessible timber along Vancouver’s shores was essential to the early growth of the city. Loggers felled cedar, fir and hemlock trees by the thousands and fed them into the local sawmills. From there, lumber was loaded onto ships for export. A lot of money was made by razing the forests.

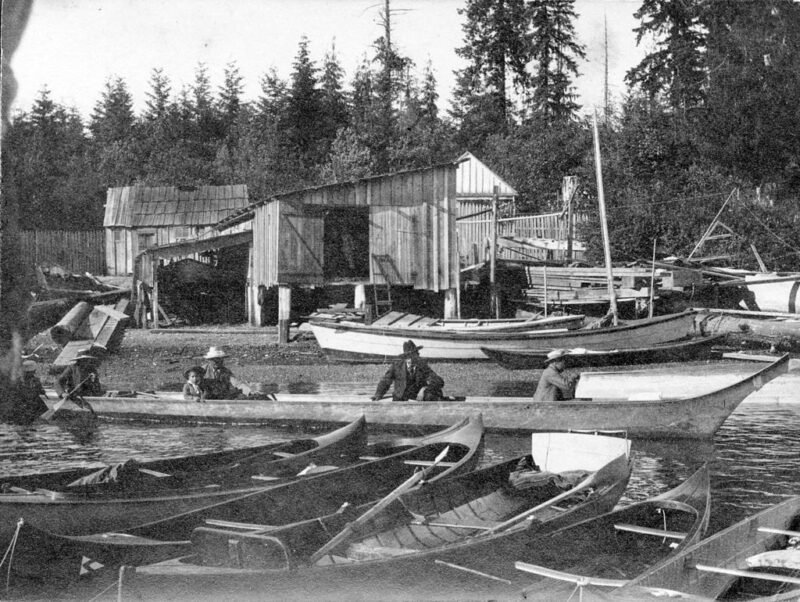

This peninsula was one of the first places to be logged. Early plans to construct a mill there — partly on the site of the still-existing Xwayxway — were abandoned due to tricky offshore currents. Instead, many of its trees were cut down, dragged to the shore by horses, and floated to the Hastings Sawmill in Gastown.

Even as its trees were being felled, the peninsula became home to more and more of those who worked in the lumber industry. Many Indigenous families still lived in Xwayxway and the nearby village of Chaythoos. They were joined by other Coast Salish people who migrated to the city to find work.

Because this land had been set aside as a military preserve by the British government, it was beyond the reach of local developers — and was a safe place to squat. Settlements grew there of people of the “fringe” ethnicities whose labour was used to power the mills, but who were unable to buy land in the city. Kanaka Ranch, a settlement of Hawaiian mill workers, appeared in Coal Harbour. A community of mixed-race Indigenous and Portuguese families grew at Brockton Point. Chinese workers made a home at roughly the site of the current-day Rowing Club.

When the City of Vancouver decided to turn the peninsula into a park, its mangy forests and ramshackle settlements were no longer a desirable image. Extensive efforts began that would transform the park into the vision of wilderness that we see there today.

A photograph in the Vancouver Archives illustrates the extent of these efforts. It was taken in 1888, just after the park was created, near the place where Lumbermen’s Arch stands today. It shows a group of workers who were in the middle of clearing land to make a perimeter road for the park. They are standing next to an enormous shell midden.

The shell midden, a layer of accumulated household waste, was left behind by the village of Xwayxway. It was more than four acres in size and at least eight feet deep in places. Today, it would be considered an archeological treasure. In 1888, it was a useful resource for the roadworkers. When photographed, they were in the process of digging up the midden, crushing its shell-rich contents, and using them to surface Stanley Park Drive.

*

When windstorms blew thousands of the park’s trees down in 2006, the Vancouver Sun described the horrified public reaction: “Our jewel, the gem in the heart of the city had been damaged and we felt it as deeply as the bite of a saw.” The storm, a natural occurrence, was widely reviled as a desecrator of the park’s pristine wilderness. But in truth, the forest is far from pristine. That residents believe it to be so only speaks to the strength of the illusion that has been constructed there.

Stanley Park was one of the earliest, and is still one of the largest urban parks in North America. In Vancouver, as elsewhere in the world, industrialization had made the city a dirty, crowded, noisy and dangerous place. Stanley Park was to be the antidote to Vancouver’s problems: a respite from city life and a taste of the natural world. Historian Sean Kheraj called it “a temple of atonement for the environmental destruction that was necessary to build the city and the province.”

The new park became a point of pride for the city’s residents. A 1903 tourist brochure boasted that in Vancouver, “Ten minutes after leaving the city one can be so secluded as to believe civilization miles and miles away!” Another, in 1936, said the park “remains today as it was at the time the ‘white man’ came… a virgin forest, and just a short walk from the shopping section of the city.” A 1980 guidebook asked, “Where in the world could 1,000 acres of ancient forest reside in the heart of a major city? Vancouver — naturally.” A modern travel website calls the park “a kind of visual spa treatment fringed by a 150,000-tree temperate rainforest.”

The widespread, but mistaken, belief that the park is a bastion of untouched nature has resulted from the careful crafting of a façade. The park’s landscape has been extensively modified. The cedars and hemlocks swallowed by the mills were replaced with Douglas-firs, which were judged to be both hardier and more picturesque. Ducks were introduced to the park’s waters, and local gun clubs invited to shoot its owls, hawks and crows. The forest is crisscrossed with roads and pathways. Its ubiquitous grey squirrels were imported from Central Park in New York, where they had proved popular with visitors. The extensive lawns and gardens are filled with imported plants.

The preservative efforts that keep the park looking natural are often themselves a struggle against nature. The park is surrounded by a wall that slows the erosive work of the sea. Its underbrush is routinely cleared to prevent fires, its insect populations monitored and controlled. All of these efforts combine to produce the pleasant vision of unchanging forest that visitors demand.

*

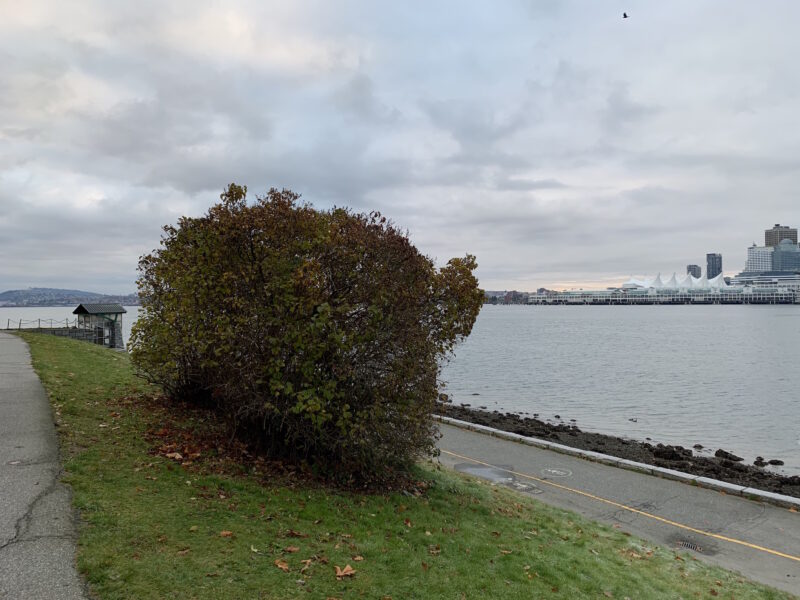

Lost Lagoon, created in 1923, is one of the most popular sites in Stanley Park. But on one chilly, moist October morning, I found myself alone there — except for a few joggers, emitting puffs of steam, who trotted along the shore. The water of the lagoon was undisturbed as well, its stillness broken only by the ducks and geese splashing noisily through the reeds or making ungainly landings on its glass-smooth surface.

The water reflected the red-hued leaves overhanging it on one side, and the buildings pressing in on the other. The effect both combined the park and the city and separated them; the lagoon seemed to straddle the two worlds. As the birds splashed and played, they momentarily obscured this reflection, but it soon returned to clarity.

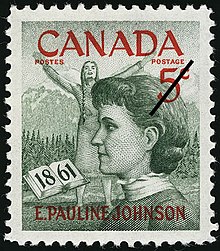

The lagoon wasn’t always here. Nor is it a lagoon. It is a freshwater pond, created to beautify the entrance to the park. It was named by Pauline Johnson, the accomplished poet and performer who settled in Vancouver in 1909. Born to a Haudenosaunee father and an English mother, she learned to straddle two worlds as well.

Johnson attained fame both for her poetry and for her thoughtful writing about her own mixed-race heritage. At a time when being a “half-breed” was a barrier to success, she used her background to her advantage. She found an appreciative audience who wanted to read about what she saw when she looked in the mirror.

She employed illusion as well, when it suited her needs. Her popularity in Britain and North America coincided with a time of general fascination with Indigenous peoples, based on exaggerated notions about their identification with nature and imminent extinction. Many of those attending her shows came for a glimpse of the exotic yet doomed culture being portrayed in the books and plays of the time.

Pauline Johnson made sure they got what they came for. She appeared for her readings in a costume that combined elements of many different Indigenous cultures. Some of the items she wore, like a scalp and hunting knife passed down from her grandfather, reflected her own heritage. Others, like wampum belts and a bear tooth necklace, did not. But they reflected the stereotypical culture that her audience desired to see.

She settled in Vancouver in her forties, and loved paddling around the city in a canoe, composing poems that celebrated the beauty of the landscape. One of her favourite places to canoe was in the waters of Coal Harbour, which at that time separated the park from the city at high tide. In her poem “The Lost Lagoon,” she described the joy this place brought her. It reads, in part:

It is dusk on the Lost Lagoon,

And we two dreaming the dusk away,

Beneath the drift of a twilight grey –

Beneath the drowse of an ending day

And the curve of a golden moon.

Not everyone was as enchanted as she was by that tidal flat. When the tide was out, it was popularly considered to be a smelly, inconvenient eyesore. But, long after her death, when the Parks Board finally decided to fill it in, her name stuck. The artificial, freshwater pond that was created there was called the Lost Lagoon. Like Pauline Johnson, and like Stanley Park, that inconvenient tidal marsh was dressed up to look like something it was not.

*

Shortly after graduating from Coqualeetza residential school in 1895, Martha Smith married one of her classmates and moved into a house near Brockton Point, at the eastern end of the park. Next to her home, she planted some of her favourite flowers, including a few lilac bushes. Martha raised her children in that home, and they raised theirs, and all of them went to residential schools, and the lilacs kept on growing.

Martha’s house, like all the others at Brockton Point, is long gone. But her lilac bushes are still there. I visited them last summer. A short walk along the seawall, watching gulls dive and play in the salty breeze, brought me to the promontory where they stand: two thick bushes surrounded by neatly trimmed lawn. The lilacs overlook the sailboat-studded waters of Coal Harbour and, behind them, the glittering high rises of downtown. The seawall was very busy during my visit, but no one stopped to look at the lilac bushes. No sign or marker indicates their significance.

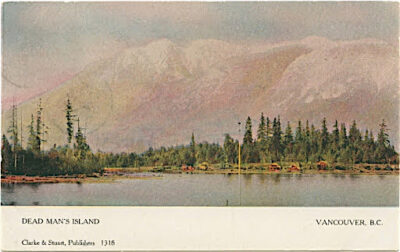

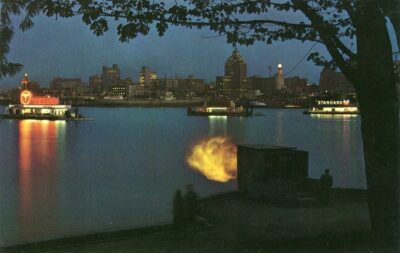

There are many other historical markers nearby, revealing that this was a busy place when Martha and her husband moved here. Hallelujah Point, so named because the Salvation Army built a mission there in 1887 — their hymn-singing audible downtown — is less than a hundred metres away. Just offshore is a naval station, built on what the Squamish called “Deadman’s Island,” a place they used to quarantine those infected with smallpox. Right beside the lilacs is a concrete survey marker, which was placed in 1863 and used as a reference point in laying out the new city. Only a few metres beyond the lilacs stands the Nine O’clock Gun, already in operation when Martha moved in.

While I snapped some photos of the lilacs, I tried to imagine what it would be like to live in a home with missionaries singing hymns on one side, a cannon booming time on the other, and nearby engineers calling out survey measurements. Colonialism had a devastating effect on the peninsula’s residents, and it appears there was nothing subtle about the process.

*

The Nine O’clock Gun has been fired nightly in Stanley Park since 1894. The cannon was retired to its current location on Brockton Point after many years of service in colonial India. Its original function was to provide the growing number of trading ships in Vancouver’s harbour with a way to synchronize their clocks, and thus to navigate the local tides. In doing so, it helped to impose the colonial understanding of time on all those within earshot. It also served as a reminder of the military might that stood behind the new government’s laws.

In the decades following the establishment of the park, the City of Vancouver used these laws to evict almost all of Stanley Park’s residents. A pristine natural reserve, it was decided, could not very well contain squatter’s settlements or “run-down” Indigenous villages. Canadian law allowed squatters to own land if they had lived on it for sixty continuous years. In a series of court cases, the city challenged those living in the park to prove that they could meet this standard.

Many Indigenous elders were summoned to the courts to testify about their memories of settlements on the park lands. Given the scarcity of property records from the time period in question, these seniors were pressed to back up the claims of those who lived in the park. The courtroom was an unfamiliar and unfriendly place for many of them, and the interpreters provided were unskilled and of questionable impartiality. The result of the trial was never in doubt.

In ruling against almost all of the park’s residents, the courts rejected the elders’ testimony as unreliable. About one witness, Justice Archer Martin wrote that “his evidence, like that of all the Indian witnesses, was vague and imaginative, incredible in parts and at times self-contradictory…. It is notorious that native Indians have no idea of time.” He was only saying in words what the Nine O’clock Gun had been announcing every evening for years.

Stanley Park’s popular collection of totem poles stands on the narrow eastern end of the park, not far from the Nine O’clock Gun, where the perimeter road makes a horseshoe bend. They are in the middle of the horseshoe, in a meadow backed by scruffy second growth trees. After photographing the lilac bushes, I decided to pay the totems a visit, although it had been several decades since I last thought to do so.

They are an arresting sight. Colourful and dramatic, grotesque and playful, evocative and mysterious, they loom over visitors — pregnant with story — and never fail to impress. They are one of the most-photographed sights in all of British Columbia, and often constitute an unforgettable first glimpse of Indigenous culture for tourists. Signs are posted in front of the totems, revealing the stories behind their creation. What they don’t reveal is that the totems are replicas of the originals, plasticized to prevent decay.

Near them, half buried in the forest, addressing the totems but apart from them, stands the first of the three portals that comprise the 2008 sculpture People Amongst the People, by Musqueam artist Susan Point. The three portals surround the totems and the nearby gift shop in a way that is both assertive and non-threatening, each of them exquisitely carved with features that reflect local history — male and female welcome figures, a pod of killer whales, a dancer holding a sacred mask. The portals comprise a welcome, both to visitors and to the totems, to the traditional territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. They are a beautiful and a powerful statement, and they underline an uncomfortable truth. The totem poles do not belong here.

The totems were erected in the park beginning in the nineteen twenties. The last buildings left at Xwayxway had been recently burned down, and the Parks Board felt it important that the site retain some reminder of its Indigenous past. They originally planned to relocate an abandoned Kwakwaka’wakw village from Vancouver Island to the vacant spot.

This plan was vehemently opposed by Squamish elders, who made it clear that placing another people’s structures on their traditional lands would be an unbearable insult. Instead, the Board erected the totem poles, taken from Northern Vancouver Island and the North Coast, considered by them to be much more picturesque than local totems. They originally stood not far from Lumbermen’s Arch.

The totem poles have since been relocated to Brockton Point. They have stood in the park for close to a century, artifacts taken from another land and used to represent this one. But the time may be coming when the poles will be removed. The passing of the years has brought increased awareness among Vancouverites that the park exists on stolen land. Changes are underway that reflect a new spirit of reconciliation.

People Amongst the People was placed near the totem poles both to make it clear whose land the park is on, and to rectify the slight offered by the foreign totems. It is one of many new monuments in the park which demonstrate a changed understanding of the history of this place.

The Squamish nation erected a totem pole in 2009, close to People Amongst the People. It celebrates Rose Cole Yelton, the last Indigenous resident to be evicted from the park. Not far away, another monument called Shore to Shore memorializes “Portuguese Joe” Silvey and his two wives, Khaltinaht and Kwatleemaat, pioneers in the mixed-race community at Brockton Point.

The park now has a reconciliation planner, who is tasked with developing a decolonization strategy for the park. Initial plans include commemoration of historically important sites like Xwayxway, Chaythoos, the lilacs and Siwash Rock; housing an Indigenous artist-in-residence at Second Beach; and public events aimed at sharing the learning and traditions of the Coast Salish people. All of these changes are being made after consultation with the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples, a marked change from the practices of the past.

Thus, for the first time in a very long time, the peninsula will reflect the desires of its original inhabitants.

*

On a recent visit to Lumbermen’s Arch, I noticed a new sign, standing alone on the grass, not far from the great cedar structure. It tells visitors about Xwayxway — the place of the mask — and its enormous shell midden. That photograph from the Vancouver Archives, of the workers at the midden, is on the sign. Looking at it, you can see reminders of past attitudes toward this land: the mangy remains of the logged forest, a fence that marks off someone’s property, the digging underway that shows how little pre-colonial history was valued in 1888.

In the time that has passed since the photo was taken, the clamshells exhumed from the midden have been re-buried beneath the road’s many layers of gravel and pavement. The surrounding land has also been overlain with alterations — new buildings and monuments, a seawall, foreign plants and animals — each reflecting the dominant attitudes at its time of creation.

Decolonization will add another layer of alterations to the park, rather than stripping away those that came before. This new layer will show some of the things that were sacrificed in order to construct the idealized space that we see today. The clamshells can never be made whole and returned to the midden, but it is a beginning to know that the midden was there. Such reminders of the land’s history will likely challenge visitors to see the park differently. And perhaps, in doing so, to see themselves differently.

On that sunny afternoon, I admired the sight of the Sisters: they looked down serenely at the children chasing each other, at the bemasked families strolling the seawall and marvelling at the view. A gentle breeze brought happy exclamations to my ears. A few families wandered over to look at the new sign, and I reflected on the way this place has always shown visitors what they want to see. Will the newest face of Stanley Park, the one now under construction, reflect a desire to recognize and learn from the wrongs of the past? Or will it comprise a pleasing illusion, one paying lip service to the darker aspects of the land’s history, that serves only to flatter its beholder?

We will have to look in the mirror and decide for ourselves.

*

Jordan Johnston grew up in Salmon Arm and now teaches elementary school in Vancouver. He recently completed an MA in the Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University. Editor’s note: Jordan Johnston has also contributed to the Pandemic Letters of Simon Fraser University’s GLS Journal.

*

REFERENCES:

Barman, Jean. Stanley Park’s Secret: The Forgotten Families of Whoi Whoi, Kanaka Ranch and Brockton Point (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2007).

Johnson, Pauline. Legends of Vancouver (Vancouver: David Spencer Limited, 1911).

Kheraj, Sean. Inventing Stanley Park: An Environmental History (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013).

McDonald, Robert A.J. “’Holy Retreat’ or ‘Practical Breathing Spot’? Class Perceptions of Vancouver’s Stanley Park, 1910-1913.” Canadian Historical Review Volume 65 (1984), pp. 127-153.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1128 Stanley Park reflections”

Jordan has written a thoughtful and sensitive expose of a Vancouver gem. Stanley Park is a testament of our collective histories as well as a wonderful place to find calm and tranquility amongst the trees.

Well Done Jordan !

Beautifully written; a joy to read. The images complement your essay well. You’ve included plenty of information that I was unaware of, and I will refer to your piece when I next walk through Stanley Park!

Such an interesting and detailed essay! I’ve lived in Vancouver for over 20 years and there is still much to learn about its history.

Great work, Jordan!

Gosh I enjoyed this. Vancouver is a special place with a rich and fresh history. Stanley Park reflects that richness, Im looking forward to the changes that will come.

This was excellent and evident of a lot of research. I really enjoyed reading it!!!

Well done! Deeply researched, sensitively portrayed in all its dimensions and through its many transformations over time. This should be the basis for a full curriculum in every Vancouver school and read by everyone who cares about the future of Stanley Park.