1122 Bowering’s magic and mirrors

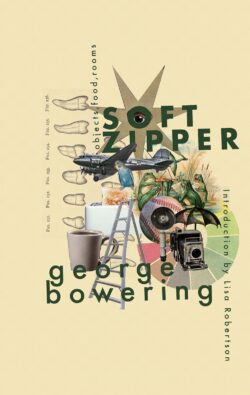

Soft Zipper: Objects, Food, Rooms

by George Bowering, with an introduction by Lisa Robertson

Vancouver: New Star Books, 2021

$19.00 / 9781554201723

Reviewed by Sheldon Goldfarb

*

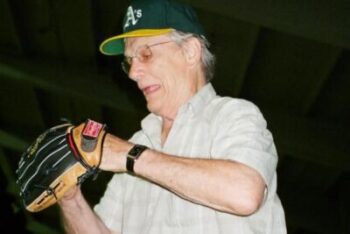

The reviewer realizes he has never read George Bowering. Played baseball with him once, or softball. UBC English Department versus SFU. There he was, all in black, playing shortstop. Maybe. The memory plays tricks.

The reviewer realizes he has never read George Bowering. Played baseball with him once, or softball. UBC English Department versus SFU. There he was, all in black, playing shortstop. Maybe. The memory plays tricks.

Well, he did read that poem in the back issues of the Ubyssey, the parody of Allen Ginsberg, “Growl,” about the student cafeteria. Does that count? Maybe he should ride madly off to read everything he can on Bowering, like he did when he came to review Al Purdy. For background. But no, he will approach this book fresh, like an innocent.

Soft Zipper: what does that mean? There’s an introduction by Lisa Robertson talking very learnedly about a poet’s prose and Gertrude Stein, but she doesn’t explain. Her introduction is called Button Kosmos for some reason, but that’s not explained either. Oh, well, best not to read introductions: they taint your view of what’s to come. But it would be nice to understand the title.

So into the first essay. This is a collection of 66 essays, each about a page and a half long, each a single paragraph. You might expect something a little obscure, modernist or post-modernist, especially after the introduction, but quite the contrary. These essays aren’t obscure at all. They are playful, wistful, nostalgic, and profound. They don’t have the structure of those five-paragraph essays imposed on hapless students (thank God), but they have a certain structure yet, usually ending with some unexpected observation, a summing up like the end of a Shakespearean sonnet, an insight, or just something to make you wonder.

The first essay is about Bowering’s father, or his father’s skullcap or “yarmulke.” Wait a minute, the reviewer thinks: is Bowering Jewish? But no, that’s not right, though he has a bust of Maimonides the Jewish philosopher in his study. Also a portrait of Lenin, the Russian revolutionary. Is Bowering a Russian revolutionary? It doesn’t appear so.

Speaking of “appear,” Bowering produces an essay about this word, especially as it appears in the phrase “Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear.” He objects to the phrase. The objects aren’t in the mirror, he says, sounding like a curmudgeon and reinforcing this notion by warning dictionary makers against confusing “imply” and “infer.” And he’s no great fan of modern gadgets; he remembers the good old days and can’t stand people who sit blankly in a doctor’s office not reading or, worse, looking at their cellphones.

But why, he says at the end of the mirror essay, can’t the manufacturers make a mirror in which reality is reflected accurately? Suddenly we are away from curmudgeon and being philosophical. When he writes about staterooms, he begins by saying that in his youth he disdained everything associated with frat boys and Rotarians, such as going to Vegas and taking cruises. But now he quite enjoys cruises, especially in his stateroom reading E.M. Forster and enjoying his room with a moving view. He has cruised a lot and does so “without white slacks or a twinge of guilt.” Wait a minute, you think, so he hasn’t gone full Rotarian (no white slacks) but has accepted the Rotarian view of life enough not to feel guilt over its pleasures. It is an almost magical, poised-on-a-tightrope approach.

There is something magical about writing, he seems to suggest in his essay on darkrooms. He loved photography; he and his friend Willy (Willy has a major supporting role in this book, burning down other kids’ forts, drinking from the cup that told him to get back to work, playing the tuba with George in high school, etc.) — Willy and George built a darkroom at Willy’s house, and it was a scary place but also magical, where you could bring something light out of the dark. All very scientific, of course, and nothing to do with the subconscious, and yet …

George lets his daughter into the book. She writes one of the essays. It’s different from his. It sounds very much modern Canadian: poetry in prose. Full of fragments. Hard to understand. If you want obscurity, that’s the essay to read. Or one of George’s soon after that, on salad, in which he resorts to run-on sentences and sounds like James Joyce. But mostly these essays put me in mind of E.B. White, with their whimsical insights and tales of growing old.

He misses certain objects from his childhood, an adult’s cigarette holder, a cribbage board, a cane. He has lots of canes himself now, and the best cane is not the efficient metal ones you can get from the drugstore, but the old battered one his wife gave him, which is always getting damaged, and which he always repairs, because if you love something, you hold onto it whatever the dents.

And there’s the comment about his grandmother only pretending to be impatient with her son (George’s father) for shaving his head before family portraits. And then there’s the visit to Keats’s room in Italy, which has been shorn of everything that would have made it Keats: what makes something or someone what they are? We seem on the verge of musing about identity.

George’s identity is of the young scallywag from the Okanagan, eating fruit from the trees (how odd to buy fruit in a store, he says) but also the old man worrying about potassium and salt, who has to spend a month in the hospital getting used to hospital food. He likes food and has several essays on vegetables, potatoes, hamburgers, and so on, but the best essays are the earlier ones on objects and the later ones on rooms. He has some great throwaway lines like the one about his picture of a rattle from his friend Greg Curnoe: “I can’t remember where it is going after my death. But that goes for me, too.” The free association of the creative mind.

And the book ends with a tale of a roommate from the Ozarks. George’s own family came from there before ending up in British Columbia, but he doesn’t understand this air force private from Tennessee who didn’t like the Sports Illustrated cover of Willie Mays standing next to a white woman. And yet, roommates, roomies: it’s an affectionate term, the last word in the book. We are all roomies with people different from us? Something like that. Maybe. Perhaps. The book makes you think. It is light as a feather, yet has deep moments too. Like a poem perhaps, but these are not poems, not in structure or syntax, but maybe in their essence. Maybe Lisa Robertson is right in the introduction: these are a poet’s writings. In any case, they are worth reading, maybe even commenting on.

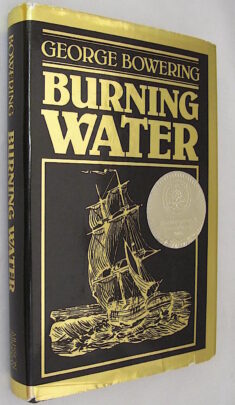

George says he spent a lot of his life explaining books in classrooms, but he bets no one will ever be explaining this one. I don’t know; I might take that bet, and if either of us is around in another fifty years we can see who will have to pay up. But if English classes are studying George Bowering then, I suppose it will be for his major works like Burning Water. The reviewer thinks he should go read it now.

*

Sheldon Goldfarb used to teach in the UBC English Department and managed the department’s softball team. He is the author of The Hundred-Year Trek: A History of Student Life at UBC (Heritage House, 2017), reviewed here by Herbert Rosengarten. He has been the archivist for the UBC student society (the AMS) for more than twenty years and has also written a murder mystery and two academic books on the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. His murder mystery, Remember, Remember (Bristol: UKA Press), was nominated for an Arthur Ellis crime writing award in 2005. His latest book, Sherlockian Musings: Thoughts on the Sherlock Holmes Stories (London: MX Publishing, 2019), was reviewed here by Patrick McDonagh. Originally from Montreal, Sheldon has a history degree from McGill University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba, and two degrees from the University of British Columbia: a PhD in English and a master’s degree in archival studies. Editor’s note: Sheldon Goldfarb has reviewed frequently for The Ormsby Review, most recently books by Jaime Smith, Jesse Donaldson, Norman Ravvin, George L. Pál, Nicholas Bradley, Sherrill Grace, Philip Resnick, and Miriam Nichols.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1122 Bowering’s magic and mirrors”