Letters from the Pandemic 31: (De)facing the music

Letters from the Pandemic 31: (De)facing the music

by Jasper Lastoria

*

The dread of a tumble gives me more anguish than the fall. – Michel de Montaigne[1]

Dear Reader,

Anger is not a set of clothing I wear well; it fits me awkwardly, emphasizing the aspects of myself I’d rather de-emphasize.

I have written about eight draft pandemic letters and the first four looked basically the same. I railed against labour inequality, particularly for front-line workers, counting myself as one of them, and I found through this frustrating process that I simply do not (yet?) possess the gravitas to write from a position of righteous anger. Instead, like most things in my life – and how I arrived in Graduate Liberal Studies, incidentally — I had to go about it sideways in order to find a path.

Sometimes I don’t know what I meant to say until I’ve said it wrong several times. This letter is about failures. This letter is about experiential learning.

*

When the mind is satisfied, that is a sign of diminished faculties or weariness. No powerful mind stops within itself: it is always stretching out and exceeding its capacities. It makes sorties which go beyond what it can achieve: it is only half-alive if it is not advancing, pressing forward, getting driven into a corner and coming to blows; its inquiries are shapeless and without limits; its nourishment consists in amazement, the hunt and uncertainty […]. — de Montaigne, p. 1211)

It helps me to contextualize this journeying as part of the intellectual process, or else I will rally against my luck, or conversely blame some flaw in myself. Neither proves especially productive, I’ve found. One has to go there to come back. And, I have to struggle a little bit to expand my mind’s possibilities, as Montaigne asserted. Here I thought I was talking about my process for a contribution to Letters from the Pandemic, but I have realized that is only a symptom I can pick out of a greater rhythm in my experience.

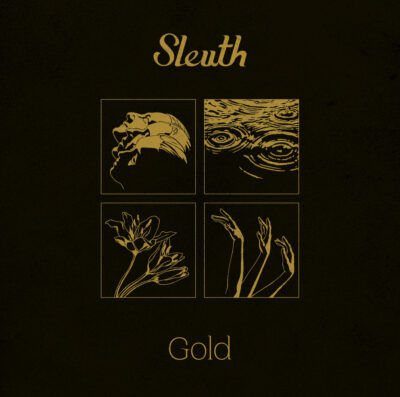

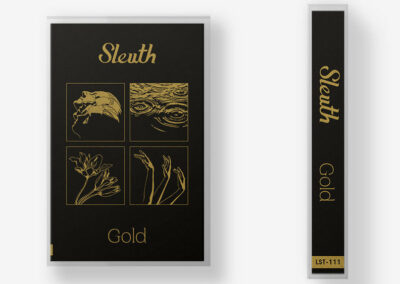

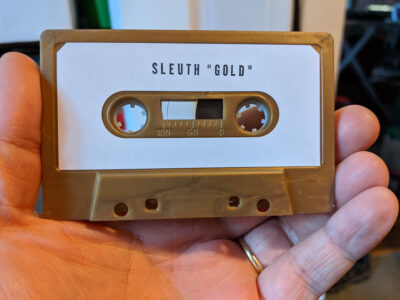

This pandemic has affected my creative perspective. Like the roadblocks I spoke of above, my experience began with a long-delayed album release, landing squarely in the first wave of lockdown. I write music, and I have been in the same band for a decade or so, and it had been five years since our last release. We worked tirelessly on this album for several years. Had any of the elements gone according to plan, it would have been released before 2020. It did not help that perfectionist qualities within me reared their ugly heads like Cerberus, and personal dramas appeared like sunbathing sirens ready to trick me into drowning. And so, May of 2020 rolled around and out went the jokingly-titled Gold, with a bit of a whimper.

*

I always have in my soul an Ideal form, some vague pattern, which presents me, as if in a dream, with a better form than the one I have employed; but I can never grasp it nor make use of it. And even that Ideal is only of medium rank. – de Montaigne (p. 724)

When I finally properly understood the term Platonic Ideal, I had a pang of recognition, followed by nauseating waves pointing to crippling failures. Like Montaigne, I possess these Ideal forms, hidden in the quietest, deepest, most embarrassed recesses of my brain for my projects, and then I concede that with all that agonizing, I view the results as “medium rank.”

Unlike Montaigne, I am unlikely to be told otherwise by an appreciative public.

The conviction of being “medium rank” frees me from the shackles of the ideal. I will not meet the ideal, and I will fail; therefore, I am free. This realization is beautiful in the way that the right combination of imperfect elements is better than the perfected imagined form. It’s why early punk music recordings are usually better than the later polished ones when the band has learned how to play their instruments and enlisted actual producers.

For many reasons — not all pandemic-related — I would describe Gold as a flop. No splashes were made whatsoever. It was less a public bellyflop off the diving board, and more a tragedy that occurred in the children’s paddling pool when everyone else was looking elsewhere. I approached this failure with a level of resigned fatigue. The pandemic offered me an out for my pride and a distraction from what could’ve been a lot of self-flagellation. Mercifully, I become a Stoic when I am tired, and early Pandemic Life was peppered with pure exhaustion from the newfound maintenance of remaining alive and technically well.

I don’t even know if my album was good or bad. I imagine I’ll come back to it in five years with fresh ears and either cringe or smile. I will know then.

The pandemic has given me opportunities to dream and scheme creatively. With the luxury and the burden of an abundance of time — if not an abundance of energy — I don’t dismiss so quickly my new ideas by identifying the roadblocks stopping me. “I don’t have time” is not a valid excuse for dumping a creative endeavour anymore.

Some months back I stumbled on an article in Vice with anecdotes from musicians, producers and songwriters on how their music listening habits have drastically shifted since lockdown. Mine have too. For a couple of months I felt too overwhelmed by this meteoric life shift to do very much. When I began to write and experiment musically again, I wrote very differently, both because I was listening to different material and with Covid, the total absence of an audience resulted in a disregard for genre, form and even words. As someone who once took great care with most lyrics (though, I’ll be honest I have definitely employed my share of “la la la” refrains) I noticed that words in the musical format had lost their effect for me.

“Only connect” — E.M. Forster’s admonition from Howards End (1910) — rings in my head daily like a tick, and lyrics became a distancing element often getting in the way of connection, stifling and muddying those desired immersive qualities in music. It seemed odd to me that I was both disregarding a potential audience, but still concerned with connection. I have not totally reconciled this slightly dissonant note, and I sense a resistance within myself to investigate it too much. As if a microscope will reveal nothing was there all along. Experientially, that would translate to looking at the muses for flaws and finding so many they become ordinary and uninspiring.

Form too has changed for me, indeed, so too any aspirations for sounding composed or correct. As a perfectionist with rather primitive and intuitive songwriting methods, placing less emphasis on polish or refined performance has afforded me the liberty to experiment. While I have in recent years been moving away from the rote, though arguably necessarily restrictive process of writing for the live gigging set-up, now knowing that I cannot play live when I haven’t been in the same room as my band since late 2019, means I have completely opted for impossible arrangements. This includes: full string arrangements, complex post-production sound processing, obnoxious quantities of synthesizers, and vocal parts that would require me to have a few identical siblings to sing simultaneously.

Amid this initial renewed enthusiasm for songwriting, I can’t help but wonder if I am now entering that bloated, self-indulgent period many songwriters experience after their initial pure, youthful expressions—a sort of musical post-adolescence full of meandering, self-referential and overly complex, but ultimately boring writing. This stage is often followed by a return to that early period with a kind of mature weariness — at least this is true for popular music, which is a general umbrella for what I do. Pop history is full of those mid-career forgettable albums — and those are by people who were at least once deemed good by popular consensus. I don’t even rank. Perhaps like many aspects of growth, even if I am aware it is happening awkwardly, it is necessary to go through such stages in order to move forward. Is this that long way around to get back to the beginning — part of the hero’s journey template?

Amid this initial renewed enthusiasm for songwriting, I can’t help but wonder if I am now entering that bloated, self-indulgent period many songwriters experience after their initial pure, youthful expressions—a sort of musical post-adolescence full of meandering, self-referential and overly complex, but ultimately boring writing. This stage is often followed by a return to that early period with a kind of mature weariness — at least this is true for popular music, which is a general umbrella for what I do. Pop history is full of those mid-career forgettable albums — and those are by people who were at least once deemed good by popular consensus. I don’t even rank. Perhaps like many aspects of growth, even if I am aware it is happening awkwardly, it is necessary to go through such stages in order to move forward. Is this that long way around to get back to the beginning — part of the hero’s journey template?

My lesson from the pandemic is that the most direct route is not always the right route. I may want to “get to the point,” but I need to stumble around in the dark for a while or else “the point” won’t make an embodied and tacit kind of sense. “The point” in question appears as an ever moving target, or like a magical amulet I’ve been carrying around out of habit that I’ve forgotten about and it only reveals its powers once I’ve gained enough experience to use it. I still had to go through those trials to access the powers.

This is a hard lesson for someone with my level of impatience coupled with perfectionist tendencies, that I must value the journey. I suspect I’ll continue to revisit this theme throughout my life, because things never seem to move as quickly as I would like, were I able to control them, and the end point will always fall short. I just need to enjoy the trip on the way a little more and watch for road signs.

A sign of a true perfectionist is not that the quality of their output is high and consistent, rather that is variable in both quality and frequency. With those Ideal forms occupying space in the mind, pairs a rollercoaster of impossible expectations, followed by the lows of resignation. So, is this letter any good? I will read it again in five years, and I will know then.

Until then, stop making plans.

Best for now,

Jasper Lastoria

*

Jasper Lastoria is jack-of-all trades with a Master of Library and Information Studies (UBC), a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Visual Art (SFU), and is currently pursuing his degree in Graduate Liberal Studies (SFU). While his areas of interest are diverse (from cryptozoology to narrative therapy), he is currently focused on LGBTQ2IA+ memoirs and autobiographies. Jasper moonlights as songwriter in the Vancouver indie group, Sleuth, and is chipping away at a new project called Anomalies 3. His pandemic plan is to read In Search of Lost Time. So far, he has failed.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] The Complete Essays by Michel de Montaigne, translated by M.A. Screech (Penguin Books, 2003), p. 733

One comment on “Letters from the Pandemic 31: (De)facing the music”

This is overwrought and meandering, but also insightful.