1093 The militant mothers of Raymur

ESSAY: The Militant Mothers: Civil Disobedience in Raymur Housing Project

by Meg Stainsby

*

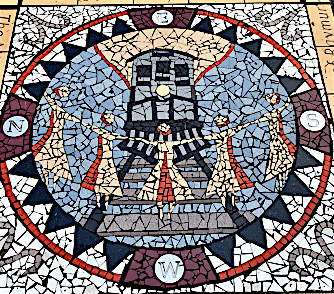

The 1971 actions of the “Militant Mothers of Raymur” was one of the first direct action campaigns in Vancouver history. The successful, swift campaign ran from early January through late March. It has been documented and celebrated in newspaper and radio coverage, in Museum of Vancouver and City of Vancouver archives, on the walls of RayCam Community Centre and Admiral Seymour Elementary School, and in a mosaic tile on the corner of Campbell Avenue and Keefer Street.

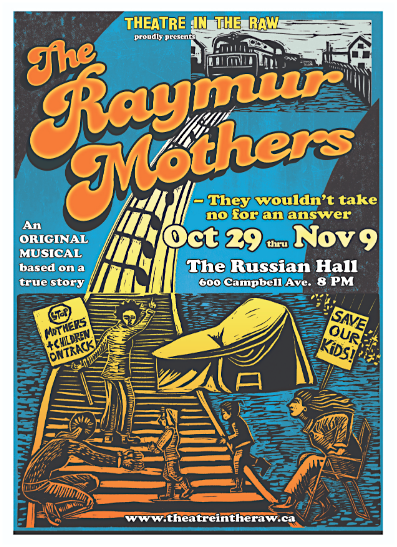

In 2014, a musical theatre rendition of The Raymur Mothers was performed by Theatre in the Raw at the Russian People’s Home on Campbell Avenue. 2021 marks the 50th anniversary of this inspiring story, which will be celebrated with an in-person gathering post-COVID – Meg Stainsby

*

Introduction

Although John Locke — and writers of many state constitutions to follow — took the human right to freedom to be universal and inalienable, he bequeathed those ruled under British-born common law the following view of social contracts: in return for the protection of property and equal rights under the law, individuals surrender the power/right to exact punishments themselves for transgressions done to them. Members of the civil society are citizens who accept this contract and abide by it.[1] Thus, Locke’s bargain can be described in ideal, unproblematic terms as one that requires surrendering some rights and freedoms to ensure others.

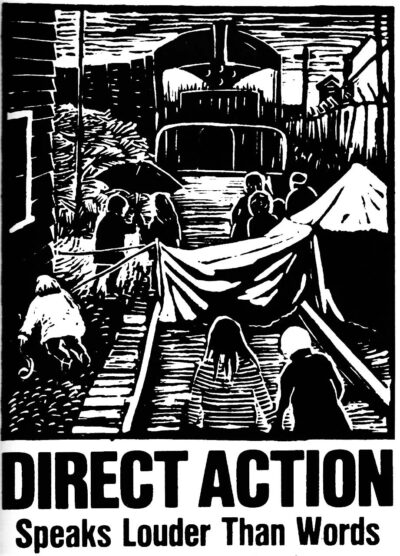

In any given civil society, at any particular point in time, individuals may find the trade-off untenable, or fraught with conflict that provokes them into action. People who have habitually been law-abiding members of such society may at times temporarily opt out of this contract, knowingly and intentionally transgressing laws or intruding upon the liberty or property of others. When they do so in the spirit of protest, to raise awareness of or provoke action regarding a situation they perceive to be unjust, we may term their action civil disobedience: the deliberate transgression of laws and societal norms, undertaken to protest publicly and seek redress for a situation perceived by the activists as both unjust and unlikely to be resolved through conventional legal, political or social avenues.

Civil disobedience, as a “strategy of securing political goals by non-violent refusal to co-operate with the agents of government,”[2] may be distinguished from less visible forms of protest—in the form of letter-writing or petition-signing campaigns, for instance—by its illegality and strategy of gaining wide-spread (in modern terms, media) attention. It may further be distinguished from criminal activity by the protester’s intent rather than by her/his action. As seen by arguably its greatest practitioner, Mahatma Gandhi of India, civil disobedience tends to be undertaken in a spirit of conscientious objecting, as citizens refuse to comply with a law in order to challenge the law itself, often because the law conflicts with other of the citizens’ values or beliefs—religious, ethical or political in nature—such that the citizens may not in fact experience full human “freedom” while bound by the disputed law. Whereas deliberate or intentional criminal misconduct tends to be undertaken in pursuit of personal gain, or to private ends, civil disobedience carries with it the sense that one believes oneself to be acting in one’s very capacity as a citizen, for the betterment of society.

In some cases, protesters occupy property the title of which they believe to be in dispute, or refuse to vacate premises when ordered by law to do so, in order to draw attention to their claims or cause. Their “weapons” tend to be placards and posters, and strategies of occupation, non-violent resistance or physical passivity in the face of legal injunctions that they remove themselves. In Canada, such actions often take the form of marches, rallies, and sit-ins or trespass, on either contested property, as in the case of First Nations blockades, or property the occupation of which will impose strategic pressures on those groups or individuals targeted by the protest, such as the office of a governmental minister.

At core, the objects of civil disobedience are freedom and justice: that is, protesters resist a law because they believe it unjustly restricts their freedoms, in ways not required for the honouring of the social contract and the security of property for all. Those acting in defiance of authority in this way can be seen, then, not as refuting or seeking permanently to break the Lockean bargain, but as seeking to re-align the elements in the contract, to achieve a more “just” balance between the powers of government and the freedoms of citizens.

Other than civil disobedience, illegal mechanisms for resisting or changing the status quo in one’s society include revolution, reformation and rebellion. Civil disobedience is akin to all of these mechanisms insofar as it shares with each the aim to better society—or the lot of some group within—and may be adopted as a strategy by participants in any of the three. The essentially passive and/or peaceful strategy common to acts of civil disobedience differentiates it as a means of protest most markedly from rebellion, which usually entails the taking up of arms.

By contrast, civil disobedience is highly compatible with reformation, the movement to call a society or at least a government to account “by insisting that pre-existing fundamental norms judge both rulers and systems:”[3] both forms of action bespeak citizens who are trying to reconcile current conditions with ideals or espoused beliefs. But whereas reformation by definition seeks reconciliation through “confirmation of old norms,”[4] the particular goal of an act of civil disobedience may be to establish new laws or behaviours, new “norms.”

But on a deeper level, civil disobedience may owe its very inception to one particular revolution—the Lockean one—insofar as the very possibility of civil disobedience exists only in states the philosophical underpinnings and/or express constitutions of which enshrine the fundamental, humanistic principle of the inalienable right to be free. Only in such states does it fall to the people to act on their conscience—under allegiance to no higher authority—when they find that their government falls short in any way of its full, just realization of its duties to the individuals by whose grace it exists.

*

A Call to Protest

In January of 1971, a group of tenants of a Vancouver, BC inner-city government housing project, Raymur Place, began a course of civil disobedience, the analysis of which is the concern of this paper. Their campaign involved disrupting train access to the Burlington Northern Railway (BNR) tracks that run parallel to Raymur Avenue north from Venables Street, crossing under the Hastings Street viaduct and terminating at the Campbell Avenue docks on the southern shore of Burrard Inlet. The group’s aim was to pressure several stakeholder groups—including the management of both BNR and the Canadian National Railway (CNR), which leased the tracks from BNR, and the civic and federal governments—into funding and building a pedestrian overpass that would provide a safe corridor between Raymur Project and the local elementary school, Admiral Seymour Elementary School, three blocks east.

By all obvious measures, the protest was a clear success; and the campaign of civil disobedience, despite a few setbacks, was relatively quick and smoothly run. A dramatic one-day train stoppage on Tuesday, 6th January 1971, was followed the next afternoon by a march on City Hall. Two months later, seeing no obvious signs of construction, protesters moved onto the tracks, camping in a tent pitched across the rails, thereby blocking all rail traffic. After two nights and three days in the tent and another visit to Vancouver’s City Hall, the protesters secured written, legally binding guarantees about the financing and construction schedule of a pedestrian overpass. And the overpass was indeed built. Site surveying began immediately, construction got underway in June, and the Keefer Street overpass opened to foot-traffic later that summer. Through non-violent trespass, disregard for property rights, and disregard for the “due process” of civic government, the Raymur Project tenants’ protest led to a timely and wholly satisfactory redress of the protesters’ concerns.

To assess the significance of these events, we must recognize and examine the transformation of the key issue of children’s safety—protection from trains—into one of justice—the children’s inalienable right to freedom, and protection of life. And to this end, we must study the protesters’ campaign closely, particularly the language and tactics employed by the activists, as well as the language used of them and their campaign by local reporters, who covered the events of January through March 1971 as if high drama.

But to go further, to appreciate what this language tells us about the social and political significance of this campaign, we must also set these events in the context of the contemporary North American and local Vancouver experience. What we find is that the women’s simple demand for a safe railway crossing for their children was transformed into a cause for social, political and economic justice by virtue of its emergence in a context of two distinct and important social and political developments of the day: the revolutionary rhetoric of class and feminist empowerment of the late 1960s; and Vancouver’s own progressivism and liberal, modernist idealism. As a result of this framing of the protesters’ concern, to deny them satisfaction would have seemed tantamount to denying them their full humanity. Thus, their protest was swift and effective precisely because it was a voice heard in the context, even the vocabulary, of other voices demanding much more radical changes. But in truth, the protesters were not out to change the power structures in their society, only to reform behaviours, bringing action in line with the theoretical values of their society; and by speaking in terms of conscience, freedom and equality, they raised voices against which governments that owed their very existence to such ideals could, not, ultimately, turn a deaf ear.

The Making of a Project

To understand the force and drama of this direct action campaign, and its impact on the imagination of Vancouverites, as implied in the media coverage, one has to see these months of civil disobedience in the social and geographical context of Vancouver in the early 1970s. The Raymur protesters’ voices expressed the frustration and anger of living on the edge of society, occupying a societal, economic and political margin. The “problem” of this margin had been the deliberate target for the energies of many of the city’s engineers, who were caught up in the spirit of civic planning and urban renewal that prevailed in Vancouver after the Second World War.

The very existence of government-subsidized housing in Vancouver can be seen as a reflection of our society’s commitment to some liberal principles of the social contract, including the inalienable right of all to life, liberty and estate—to live free from harm, and to have one’s fundamental human needs met. In Canada, in principle, governments have traditionally assumed responsibility not only for ensuring the availability of appropriate housing but also for respecting the dignity of the individual citizen, in part by ensuring that a minimal standard of living is enjoyed by all. In this spirit, “slum clearance” schemes were undertaken in several major Canadian cities from the late 1940s throughout the 1950s. But such efforts were not altruistic: improvements to the “blight”[5] of Vancouver’s downtown east side, for instance, were seen by the planners of the day as sound investment. In the spirit of post-war rebuilding and renewal, local Vancouver engineers and urban planners optimistically turned to the most dilapidated sections of the city with a striking energy and commitment to “progress.” From the start, the eradication of “urban blight” was viewed from the dual perspectives of both social and economic desirability, as evident in a 1950 study by Professor Leonard Marsh (notably holding a cross-appointment to the UBC schools of both Architecture and Social Work):

It is well known that slums and blighted districts are “deficit areas,” i.e., they cost more to the community (for the services in health, welfare, delinquency, fire prevention and policing they involve) than the municipal revenue they yield in property taxes, etc. … [In Vancouver], in round figures, the city pays out every year twice as much as it derives in revenue from this area. … Bad housing and poverty are, of course, closely interrelated; but it is too often forgotten that social assistance—of which today there is a great variety—cannot be constructive or lasting if it is given in an environment which drains away morale and self-respect. The direct costs of slum living are borne by the residents—in cramped homes, overburdened housekeeping, handicapped schooling, family tensions, poor health, disease, accidents, and delinquency. The social and economic costs include not merely the expenditures on health, welfare, delinquency, policing, etc.—which today are growing more familiar—but the fact that many of the services are counteracted and wasted.[6]

By 1950, the city was already well invested in its campaign for social and economic renewal. Significantly, Marsh’s influential planning and discussion paper reflects the already-firmly held modernist expectation that society can be improved, that “constructing” the “new city” is possible, and moreover that it is the role of government—at all levels—to foster such improvement through social as well as economic projects. Indeed, in its own promotional literature, government acknowledges not only that each human has a right to certain freedoms, but also that government is the agent by which those freedoms will be delivered and protected. The moral imperative here is married to the economic, with government on the hook for both.

The 1950s in Vancouver was also a decade marked by a modernist conjunction between architecture and social planning, as art and the aesthetics of the living space were seen as linked: “The equation between art and living was the cornerstone of fifties’ modernism.”[7] The prevailing view of the artistic community in Vancouver in the late 1940s and early 1950s was that “the voice of the artist [needed to be] heard in the realm of architecture”; indeed, “the central belief of the modern movement, simply, [was] that good design had an uplifting moral and spiritual effect.”[8] A local exhibition, City for Living (ca. 1945), reflected the view that “city planning would produce the ‘happy family.’”[9] Architecture had moral purpose: like modern art, the good home “could serve ‘the need for greater solidarity in the family unit.’”[10] A brochure for the 1949 exhibition Design for Living reads, “’The good home is said to be the nursery for domestic virtue and in turn a guarantee of a healthy community”; and “[g]ood design is essential to better living, and better living improves the standards of the entire community.”[11]

Thus, the plan to demolish the “urban blight” and construct shiny new housing projects in the most impoverished, derelict neighbourhood in Vancouver could never be seen in a purely economic light: from its inception, the plan was infused with moral and aesthetic sensibilities, too. Captain George Vancouver is reported to have said, upon landing on this city’s shore more than 150 years earlier, that all this bounteous natural landscape needed for its promise to be fulfilled were the “industry and ingenuity of Man:”[12] local industry and ingenuity, it seems, were in abundance after WW II. As the buildings went up, so too rose people’s expectations that urban poverty, sickness and unemployment could be eliminated. Witness the background soundtrack to a municipal video—the joyful sounds of healthy, safe children playing—as the construction of the McLean Park towers is celebrated as if a mini New Jerusalem.

The Immediate Context

Out of these economic, social, moral and aesthetic impulses arose a social civic experiment, the provision of concentrated clusters of housing for the city’s poorest inhabitants. And while anticipated in the abstract as a kind of paradise regained, back in the concrete realm of the “slums” there were some practical problems, including the long-standing issue of safe railway crossings. The Raymur Place parents-cum-protesters of 1971 inherited this historical conflict, for which resolution had been many times sought and even promised but never achieved.

From the early days of Vancouver urban development, safety upgrades at area crossings were problematic because of disputes over financial responsibility for any overpasses. In 1914, City Council got so far as tendering construction contracts for four crossings; however, only the Hastings viaduct was built before the First World War intervened, and available fiscal and human resources were redirected. Despite the loss of momentum in 1914, the planning work done that year did facilitate eventual construction in part by forcing some clarity, if not final resolution, on the issue of financial responsibility: the board of railway commissioners in 1914 ruled that the railway would be liable for “a substantial share of the costs if the city decided in the future to proceed with more overpasses.”[13] Marsh’s 1950 urban renewal study calls for the rail line to be used as a territorial boundary, defining the eastern limit of the property to be affected by redevelopment proposals. This same plan recommends that a new elementary school be built west of the BNR line, to accommodate the concentration of children expected to become resident of the housing Projects, once completed. Neither recommendation was adopted. When Raymur and other Projects were being planned and built in the 1960s, safety and traffic concerns over the proximity of the BNR lines were again noted but not addressed.

Less tangible but no less real were concerns over the socio-economic impact on the neighbourhood of building the Projects. Such concentrations of poverty, and of poor people, did alarm some local residents—particularly local home-owners and business proprietors. But initial resistance to Project construction lessened significantly once the first, McLean Park, opened to tenants;[14] subsequently, many of the fears and suspicions about the effect of these residences upon local property values and community safety abated.

Fears aside, there is no question that the demographics within the geographically small areas of the Projects were uncharacteristic of those in the city as a whole: before the “renewal”, ten per cent of families living in the “blighted area” were headed by single-parents;[15] in McLean Park, by contrast, Stratton’s survey of tenants indicates that “[n]early half the families (other than pensioners) accepted in Vancouver’s most recent project are broken families.”[16] This neighbourhood already contained a disproportionate concentration of the city’s neediest populations—the elderly, single-parent families, families with many children, the unemployed and the unemployable, the disabled, and recipients of social assistance; common sense suggests that indeed the density of these populations was only intensified within, and by, government-subsidized housing Projects. Conversely, and predictably, the percentage of residents of this area who were home-owners rather than renters was—and continued to be—below the city’s average.[17]

Still, official expectation seemed to be not that the poor would be ghettoized in these Projects: rather, in this era of perpetual improvement, tenants were expected to need only temporary support as they “found their feet” economically, and would then move out as they became able either to secure more grand rental accommodation or, better yet, to buy their own property. Thus, the Projects were seen as filling a gap, socially and economically, and represented one piece in Vancouver’s multi-faceted plan for “progress.” While social engineers and city planners acknowledged early in the 1950s that the “margins” present dangers, that the city’s areas of socio-economic and geographic “blight” could be wholly undesirable places, they went ahead and constructed the Projects within and as part of these margins, with the intention that all citizens should thereby participate in the benefits of modern, progressive society: living in clean, stream-lined housing “parks” that offered a kind of social levelling—and thus dignity—to the most underprivileged of the city’s inhabitants.

What civic planners may not have anticipated was that the concentration in particular of poor, single women in such places, at a time of increased social activism on behalf of women (among other groups), and of feminist consciousness-raising in particular, might help foster all sorts of activism and protest. Granted, BC has long been labelled within Canada as unusually volatile, socially and politically, and as tending to polarized conflicts. But the late 1960s offered particularly intense politics throughout North America, and the rise generally of social activism, including the civil rights and feminist movements, and anti-war protests. This was an era of social revolution in North America, a time of challenge to the fundamental construction of society to the advantage and privilege of the few, a time when a wide variety of “illegal” means of protest and demonstration were in use.

A brief scroll through the pages of local Vancouver papers of January – March, 1971 provides a useful reminder of this larger landscape of social and political activism, protest and change that is the back-drop to the Vancouver story. In February 1967, the Liberal Government of Canada convened the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, which reported out to great publicity in December of 1970. That same year—an example of local feminist activism of the time—the Abortion Caravan rolled out of Vancouver, heading for Ottawa, to demand decriminalization of abortion and equal access for all women to abortion services and affordable birth control. Later in 1970, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) grew increasingly militant, threatening terrorist action; the October Crisis that year—the kidnapping and murder of Pierre Laporte and Prime Minister Trudeau’s quick introduction of the War Measures Act—prompted many Canadians to fear that they no longer had “inalienable rights” at all, and provoked a national outcry and debate that still rages decades later.

Locally, labour was also restless in the winter of 1970-1971: Vancouver bus drivers, railway workers, dockworkers and teachers all engaged in strike action. And on the cultural front, in the spring of 1971, the annual Stanley Park “Easter Be-In”—a legacy of anti-war protest rallies that had been transformed into Vancouver’s spring music-fest, a communal celebration of peace along the lines of a mini-Woodstock—was being threatened by City Council. These were times when radical challenges to status and power were daily fare in the local papers, and a time when action—and activism—was valourized in the press.

The protests by residents of Raymur Place must be seen as part of this time: a time of social revolutions on several fronts, a time in which justice—in the form of equality, for children, for women, for the Vietnamese, for Black Americans, for the working man—was being demanded regularly, loudly. The protests erupting in the downtown east side of Vancouver in 1971 were thus one local expression of the well-understood, pan-North American protest voice characteristic of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The protesters expressed the strength and conviction seen elsewhere in this time of broad, societal changes, and were as successful as they were in part because their cause resonated with contemporary, popular ideas about the injustice and untenability of economic and sexist discrimination.

These two dimensions of the context for the Raymur protest—local civic progressivism and broad social revolution —must be kept in mind if we are to understand how the campaign of civil disobedience was acted out and interpreted by its audience(s). The broad social implications of the protest seem to have been what appealed most about the story to the journalists of the day, who quite liberally quoted the protesters, as the latter couched their actions and demands in rhetoric of class antagonisms and feminist empowerment. And whether or not the protesters were aware of the modernist vision of urban renewal and social planning that informed the building of the Projects, they played into and benefited from this vision, fraught as it was with a moral and economic idealism that assigned to government the central role as the principle agent of progress. While holding rail company profits hostage, the protesters also held governments to account for failing to follow through on and to honour the liberal values and idealism that had infused the building of the Projects from the start.

The Protest

In February 1967, just as construction on Raymur was nearing completion, a twelve year-old boy lost six toes when run over by a train in the disputed section of track. This event, coupled with the influx of children moving in to Raymur over that autumn, prompted local parents from across the Strathcona neighbourhood to petition City Hall for the construction of an overpass. In August 1967—four years before the BNR became the site of protest and civil disobedience—Vancouver City Council commissioned a feasibility study of the building of such an overpass; the next month, while the study was getting underway, the Canadian Transport Commission directed BNR to build a fence along the portion of track that runs parallel to the Raymur development, in an effort to force pedestrians to cross at the southern end—at Union Street—an intersection with greater visibility and a crossing signal. The fence was not built at that time; neither was action on the overpass forthcoming. But a crisis did not emerge until the Raymur tenants themselves came to be directly affected by the danger of the Pender Street crossing.

To get to Seymour School, children from Raymur crossed the tracks at Pender Street at least twice daily—four times if they walked home for lunch. The crossing was unsupervised and unregulated. Children negotiated not only moving trains but also “parked” trains, trains queued up and blocking Pender Street, awaiting access to the dockyard and terminus less than half a mile to the north. Children were known to scurry underneath the stalled train cars, or clamber over the couplings between cars—at times undertaking these maneuvers on/under/over trains as the trains shunted back and forth, or before they were fully stopped. For good reason, local parents were worried about their children’s safety.

In the fall of 1970, when the six year-old daughter of Carolyn Jerome, resident of Raymur, started attending Seymour School, Jerome began to circulate a new petition, asking Vancouver City Council and the federal housing agency responsible for subsidized housing, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Commission (CMHC), to act on the need for the long-awaited overpass. In addition, some Raymur tenants telephoned administrators at both CNR and BNR offices to request that an overpass be built. Despite verbal promises from City Hall, the parents saw no evidence of an overpass coming to their neighbourhood any time soon. It is in this local context that a small group of parents from Raymur (a group fluctuating in size from five to twenty-five individuals) planned and executed the first campaign to disrupt the railway companies and governments in order to force both groups into action. They moved onto the Burrard Inlet line of the BNR tracks on the morning of Tuesday, 6th January 1971.

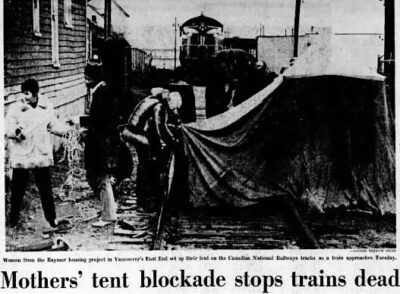

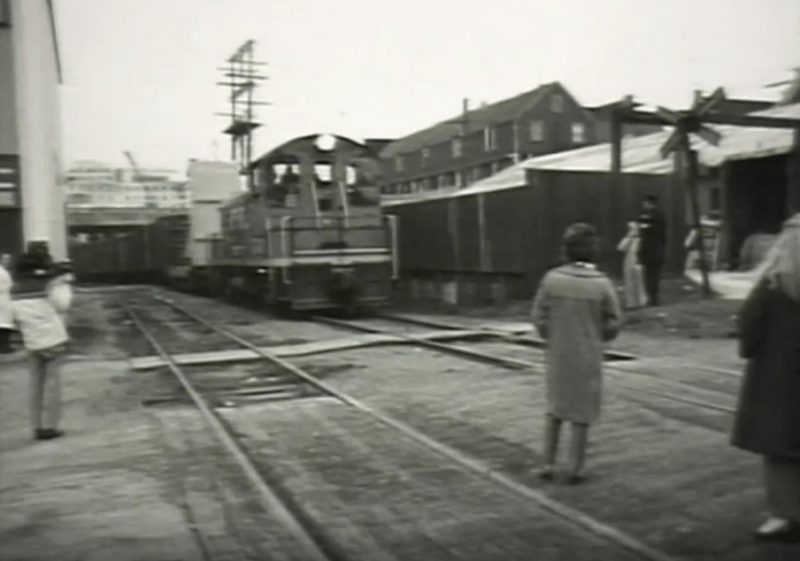

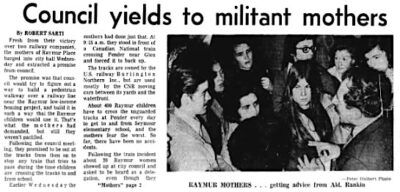

Before analyzing the finer points of the campaign and its presentation in the local papers, we should review some details. On this first day of protest, parents and children “forced a long [CNR] train to grind to a halt.”[18] The protesters prevented any trains from moving through the Pender Street crossing for the rest of that school day, retiring their protest in the evening. The next morning, a group of twenty women “barged into city hall … and extracted a promise from council[,] … that council would figure out a way to build a pedestrian walkway over a railway line near the Raymur low-income housing project, and build it in such a way that the Raymur children would use it.”[19] With this promise in hand, the group left City Hall. They also received from CNR an agreement not to use or allow use of the tracks during set times when children were in transit to and from school. Raymur parents undertook to patrol the tracks during these peak crossing times, acting as crossing guards for their children.

This arrangement persisted only until 27th January, when, the protesters claimed, a CNR train travelled through the disputed section of track during restricted times. The mothers blocked the rails once again that very afternoon. The CNR, for its part, maintained that this incident was the result of a misunderstanding of the agreement; after the company repeated its commitment to abide by the now-clarified terms of that agreement, the blockade was withdrawn. But the incident prompted the protesters to return to City Hall, to demand proof that progress towards the construction of the overpass had been made: specifically, that federal money had been released to help fund the project; and that expropriation of the necessary lands had been secured by the City. The mothers were growing cynical of the pace of bureaucratic process: “‘If it’s not now, it means no,’”[20] said spokesperson Judy Stainsby. When Council tried to put the mothers off for two weeks, the mothers countered by saying that unless they had the proof they sought within seven days, they would wait for Council’s decision “right in the middle of the tracks.”[21] Council delivered its assurances to the protesters within the week.

In terms of activism and protest, February was a quiet month, but the trains themselves grew noisy. According to the Raymur tenants, CNR trains began sounding their whistles to an increased extent, beyond legal or safety requirements. The protesters interpreted the whistling as harassment, retaliatory action reflecting the hostility of the railway crews. Jerome told reporters, “‘they’re getting back at us with their whistles…. Every half hour all day they blow those whistles long and loud. The guy who comes through here at 4 a.m. really hates us. He leans on that thing for a good 60 seconds…. They’re hoping we’ll apologize and ask them to please stop blowing the whistles.”[22] The protesters were not inclined to apologize. But so long as the CNR trains complied with the agreement—noisily or no—they did stay off the tracks.

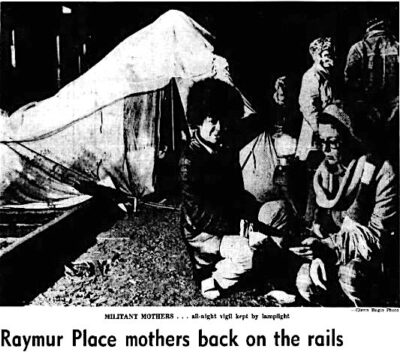

Trust was fully lost on Tuesday, 22nd March 1971. According to a press release given out by the protesters the next day, a CNR train “sped” through the Pender Street crossing at 8:32 a.m.; the CNR, for its part, maintained that the train in fact had traveled through the intersection—at a safe speed—at 8:27 a.m., and was therefore not in violation of the agreement. The CNR released its own statement to the effect that “The mothers of Raymur Place … have been misinformed.” Whether misinformed or no, the protesters became active once again, swiftly. They called a meeting of concerned Raymur tenants that evening. The next morning, they occupied the tracks once again, but this time they brought a tarp, warm clothes, sleeping gear and cooking utensils, and they began constructing a tent in which they proposed to live until such time as three demands were met. The demands were as follows:

- Proof [must be] produced that the Canadian Transport Commission has released the funds for their share of the cost of the Keefer Street overpass.

- Proof [must be] produced that the City of Vancouver has acquired title to the Keefer Street road allowance where the overpass will be built.

- The railway companies [must] post a bond to keep to the terms of the original agreement of January 6 until the overpass is completed and the Pender Street crossing fenced off. We have accepted the verbal and written promises of the railway officials and they have proved worthless. We demand a promise of the kind they themselves respect—one backed by money.[23]

After two nights and three days, two aborted attempts on the part of the railways to evict them by court order, and some intense negotiating through a lawyer who volunteered his time to the group—only then did the protesters pack up their camp and move off the tracks. When they went, they went holding a court injunction that obliged the railways to keep to the restricted hours of use of the disputed section of track, and having received proof that federal funds had been released, land title acquired by the City, and contracts let to tender. There was one further dispute over an alleged violation of the agreement (in May), leading to no action by the mothers. The overpass opened to foot passengers before the start of the next school year in September 1971.

From even these few details, several salient points become clear. First, and centrally, the women identified themselves as keeping and honouring values not evident in the behaviour of those with whom they had to deal—but values that the City and federal agencies, if not the private corporations, ought to have held, and would likely claim to hold, if pressed. As protectors of children, the women challenged the “bottom line” interests of the railways, and they articulated their alienation from the bureaucratic processes and property interests of government. They also identified themselves as being harassed, betrayed, lied to, dismissed and undervalued as human beings.

Quickly, the conflict came to be characterized in the media, and understood by all, as concerning the inherent worth of each individual: the threat to the children was not identified by participants as merely a local question of safety but as a broader one of their entitlement to freedom from harm and from danger—freedoms taken for granted, the protesters said, by the more privileged members of society. In demanding action, the residents of Raymur Place threw back at civic officials their own values and language, as well as some revolutionary-sounding rhetoric, picked up no doubt from the vibrant social activism of the day. Thus, the protesters demanded that in fact—not only in theory—they and their children be afforded equal worth. And in doing so, they raised and critiqued the equation, so common in the world of social contracts, between the values of human life and of property, including profit.

There was a discernible class or socio-economic thrust to the women’s presentation of themselves as “fighting a good fight.” The protesters were demanding that society afford them the same rights that the women perceived were being afforded to members of these other, more powerful groups: the employed and the propertied. When interviewed as the camp was being set up, Jerome quipped, “If this was Kerrisdale [one of Vancouver’s most affluent neighbourhoods], they would have acted quicker.”[24] And yet, ironically, although quick to adopt the rhetoric of class discrimination and portray themselves as weaker than the forces arrayed against them, these women were not revolutionaries: they weren’t out to topple the Kerrisdale hegemony, whatever it might have been; they wanted the rights supposedly guaranteed them in a liberal, constitutional state such as Canada—their inalienable right to freedom, to equality with others on matters of life, liberty and estate. For this reason, their actions, while radical and unorthodox in means, were directed at reformist, not revolutionary ends.

That the protest was seen more centrally as part of a pattern of eruptions of feminist activism seems clear from the coverage in local papers, especially The Vancouver Sun and The Vancouver Province. From the start, these papers characterized the protests as a “mothers’” initiative, although on day one the Sun column acknowledged that the women were “backed up by a few fathers”: “The demonstration began before school opened when 10 mothers from Raymur Place low-rental housing project began lining up across the tracks.… At about 9:15 a.m. a CNR train, ringing its bell and steadily sounding its whistle, attempted to cross an intersection but came to a halt in front of three rows of women and children.”[25] In describing the protesters as they stood, unmoving, a CNR train bearing down on them from the north on its way out of the area, after having delivered its grain to the docks, local headlines characterize the women as Davids in their battle against the powerful Goliaths of city government and railway companies. Reporters’ sentiments seem generally to favour the protesters, cast as moral vigilantes championing a just cause—the protection of children. At times, as on day one of the protest, the tone of the coverage is bemused, indulgent, sometimes ironic, as if protesters are more entertaining than radical, more amusing than threatening, as in the first Sun headline, which read “Raymur Place Train Holdup,” invoking wild-west, Hollywood-style ambush rather than serious, planned civil protest. The prospect of these rag-tag maverick women presuming—and managing—to humble a powerful locomotive, and the greater forces it embodied, was met with one part amusement for every part concern.

The protesters were not averse to having their maternal status become the focus of media coverage: far from it, they appear to have been keen to play into a dualistic reading of the conflict as one pitting maternal duty to protect life against corporate/civic interests to protect property and realize profit. The newspaper coverage repeatedly emphasized that the battle was one of the powerless against the powerful: women—designated most often with the title “mothers,” but also identified as tenants and protesters—struggle against the men who, as representatives of corporations or government agencies, are identified by both name and occupational or political status, as in “Burlington trainmaster C.J. Ferderer” and “CN assistant superintendent E.E. Grover.”

One can hardly fail to notice that the “mothers,” despite their tenacity, lacked the power to command the respect afforded automatically to politicians, lawyers, civic officials, corporate managers. These women were not property owners, workers or taxpayers, certainly not professionals: on day two of the conflict, as the protest shifted from the tracks to Council chambers, headlines refer to the “Militant Mothers.”[26] The notice calling the organizing meeting on the evening of 22nd March ends with the invitation to participants to “bring your children [to the meeting] if necessary,” reflecting the protesters’ sense of themselves as “child-friendly,” in contrast with their uncaring opponents. Weeks later, in a press release issued to local papers and radio stations, the protesters adopt the “militant” label for themselves. Their statement begins, “Militant Mothers Move Again,”[27] implying for them a positive spin on an adjective which, while seemingly used with some admiration by local journalists, is more commonly paired pejoratively with “feminists” as a derisive label for assertive and vocal women.

In similar ways, the framing of the protesters’ concerns as a “women’s” or a “mothers’” issue, let alone the hint that “militant feminists” were involved, was problematic from the start, bringing to the protesters both advantages and disadvantages. Among the costs, the women were subjected to threats and insults particularly tailored to them as women: the stereotypes and stigmas about women, especially the “single mother on welfare,” were reflected in the remarks of one thwarted CNR worker who is quoted as yelling at the mothers the first time they blocked his path, “‘Get out of bed and take your kids to school.’”[28] The stereotype of “welfare moms” as inherently lazy and negligent mothers was one under which female residents of subsidized housing had particularly to labour (just as, one might argue, they continue to labour today). The stereotype was not new in 1971, either: as early as 1959, we find studies arguing that Canadians must become conscious of the “stigma [they ascribe] to the state of being ‘poor’”, and urging us to learn to differentiate between “troubled” and “poor” families, and those who, by their own aberrant or antisocial behaviour, show themselves to be “troublesome.”[29] And we can further infer that the antipathy expressed by the CN worker was not remarkable, from the somewhat defensive remarks one tenant was moved to offer, during an earlier review of safety issues at five Vancouver housing projects, including Raymur:

Lest it be said, as it is so often said, that the mother’s influence should impel the child to perfect behavior even when he is on the way to school and she is home minding the baby or tending an invalid, let it be stated here and now that some of the most promising children are constitutionally venturesome, and that in any case incessant caution is not a characteristic of the kindergarten and grade-school set.[30]

Clearly, no matter how socially well-intended, official housing policies of urban renewal, designed to provide safe, affordable, and dignified housing for low-income families—many of which were headed by single mothers—were not likely in themselves to eradicate biases against women, or against the poor, least of all those against poor women. To the extent that these Projects concentrated and thereby made more visible this particular population, they may inadvertently have led to greater incidence of women having to hear such remarks hurled at them. Certainly, by placing themselves on the front lines, and in the headlines, the protesters made themselves especially vulnerable as targets for the expression of such stereotypes and prejudices.

The protesters’ primary identification as “mothers” played to their advantage at times, too, even while they recognized limitations to their power because of this status. At least popularly, in our culture, moms are good people, people we like to see succeed in their causes. When female protesters gained victory over/from the male officials at City Hall on their second day of action, headlines announced, “Council yields to militant mothers,”[31] and “Moms win the day.”[32] The councillors whose meeting was derailed, by contrast, are described as having been reluctant to meet with these protesters, and come across primarily as annoyed at and frustrated by the women’s tactics, particularly by their unorthodox behaviour, their failure—or refusal—to play by the rules.

One alderman, Walter Hardwick, identified as “a university professor,” is described as “lecturing the women on the proper way to get results at city hall.”[33] Presumably, he assumed that the mothers, hailing from the domestic sphere and untutored in the public realm of politics, were ignorant of bureaucratic, governmental protocol. But not so. The women seem to have understood very well that their effectiveness arose directly from and precisely because of their unorthodox and radical tactics. They were not inclined to bow to pressures—or advice—that they return to conventional, approved processes to have their cause heard. After hearing Hardwick lecturing on this point of procedure, one protester is cited as shrugging off his advice: “‘That doesn’t impress me…. We stopped the train. That’s why council listened to us.’”[34]

In fact, the protesters had rejected an earlier strategy to picket City Hall precisely because they felt that City Hall could ignore them if they spoke with only their own voices. Quite cannily, the protesters, recognizing that money talks, provoked the railways into adding their corporate voices to those demanding that City Hall “do something”: Jerome noted, “The railways are upset because we are ‘interfering with the economy of Canada.’”[35] Thus, recognizing their own limited powers, these women/mothers found both direct and indirect means to compensate for these limitations.

Our society’s complex and ambivalent cultural attitudes towards women are also revealed in the more courteous and solicitous responses the protesters elicited, at least at first, from some of the men with whom they dealt during their campaign. W.S. Beaton, district inspector for the Canadian Transport Commission, sounds conciliatory and respectful when first speaking to the women on the tracks, on day one of the protest: “‘I will write a letter to Ottawa’ [he began]. ‘I agree it is dangerous. We are going to do something about it’”[36] And the official response from the CNR, the lessee of the line and principal user of the track, was initially conciliatory and accommodating: while acknowledging that it was under no legal compulsion to alter schedules or crossing procedures, the CNR voluntarily undertook to restrict train travel through the contested intersection to times when children would not be expected to be crossing, “until such time as the City of Vancouver, the Burlington Northern and the Canadian Transport Commission completed arrangements for a pedestrian overpass.”[37] Despite this apparent civility, however, the men clearly had an array of powerful forces on their side. With little provocation, representatives of the railway dropped the veneer of courtesy, resorting to overt threats to have the women forcibly removed. Beaton, cited above, moved quickly from acknowledging the legitimacy of the women’s concern to pointing out (solicitously?) that the protesters’ actions were “‘not just a misdemeanour, [but] … a felony,’”[38] invoking the force of the law.

Initially, the point that the protesters were illegally occupying property belonging to a private railway corporation does figure surprisingly little in the coverage of the campaign. But once the protest escalated to the full blockade—that is, once the CN’s financial interest in the action increased sharply—the CN spokespeople ceased expressing their “shared” concern for the children’s safety and began instead focussing on the economic costs of the action. Two CNR officials interviewed on the second day of the March blockade raised the prospect that the mothers’ action would force the lay-off of dock workers—hard-working men—by preventing grain and pulp shipments from being processed, thereby denying the men their right to make a living.[39] Looking on as the women pitched their tent on 23rd March, one CN official is quoted as remarking, “‘I hope you’ll have protection after dark, for your own safety.’”[40] Several times, railway officials made direct references to “resorting to legal means” in their efforts to pressure the women to abandon their blockade. The initial mask of courtesy was replaced quickly by hostility and threatening behaviour, once the men recognized that their efforts were not eliciting the desired compliance from these persistent women.

Somewhat sadly, perhaps predictably, the protesters’ victory is depicted as having come about, in the end, as a result of the kindness of two strangers—men, both lawyers, both volunteering their services pro bono to help the women negotiate for their cause with a political, legal and corporate system not inclined to respond favourably to them or their tactics. First, the protesters caught the eye of an approving (at least, a supportive) alderman—a young Harry Rankin, a Left-leaning Vancouver lawyer who would emerge later in the 1970s and ’80s as one of the city’s most colourful and notorious councillors. From the start, Rankin appears to have seen theirs as a cause for justice. When the group first descended upon City Council, Rankin took up their initiative, entering a motion before Council that city engineers “devise a scheme that would guarantee the overpass would be used;” he then followed the women out of chambers to offer them (unsolicited) advice as to “how best to guarantee that the City kept its promises.”[41]

Rankin also took it upon himself to keep up with developments of the “tracks issue” during the next month or so: after the conflict over the alleged violation of the agreement on 27th January, the alderman wrote to the City’s engineer for an update relating to the protesters’ outstanding concerns—negotiations over expropriation of property and request for federal funds (from the Canadian Transport Commission) in partial support of construction. In this same memo, he also raised concern about the increase in frequency and length of train whistles being used near Raymur.[42] As an “insider,” he became an effective ally for the mothers, and is pictured in several press photos counselling the rallying women.

The second lawyer to take up the protesters’ cause was Bruce McColl, and like Rankin he seems to have acted out of good will and sympathy for the mothers. McColl’s role in securing the mothers’ victory was, however, to have been far greater than Rankin’s. His power derived in some measure from his status as partner in a prestigious Vancouver law firm at the time—Farris, Farris, Vaughan, Wills and Murphy. Having taken an interest in the mothers’ cause, McColl took it upon himself to scrutinize an application for an injunction to force the mothers to withdraw their tent from the tracks. This injunction was sought by the two railways, BNR and CNR, acting together. McColl found that the injunction had not been properly served on one of the protesters, Carolyn Jerome, and he so notified her and made representation before the presiding Judge Mackoff to this effect. Mackoff found the application faulty and dismissed it. With the mothers still in their tent, the railways immediately began drafting a second injunction, but McColl again intervened, as “friend of the court,” and succeeded in having this injunction dismissed as well.

These actions effectively left the mothers free to remain on the tracks through the weekend, pending a hearing the following Monday; this in turn would mean that the railways faced the prospect of losing at least another three days’ shipment of goods along the lines to and from the docks. But McColl stepped in again: he drew the two sides together and facilitated an agreement both sides could live with. Appearing again before Judge Mackoff, the parties signed the agreement Friday afternoon. In his closing remarks, Mackoff praised McColl for his efforts in championing the unrepresented protesters: “‘This young man is acting in the finest tradition of a young lawyer,’” the judge told the court.[43]

So the saga of the “angry mothers” ended with them securing the guarantees they demanded. The overpass was built soon after. From the perspective of class, sex and power analyses, what is striking about this ending is the extent to which the mothers’ triumph came about through the agency and interventions of male champions, assisting the women to a goal they may or may not have been able ultimately to secure on their own. Despite embracing such charged labels such as “Militant Mothers” and adopting activist tactics, the protesters simply had little power other than that which came to them by virtue of their appeal to the public’s sympathy. This sympathy should not be underestimated: the women did easily win some high moral-ground by carrying around placards reading “Children vs. Profit” and “What Value has a Child’s Life?” But with no property of their own, they had no direct form of economic interference to offer: they could not exercise the privilege of the land-owner who wishes to force action from City Hall and to this end withholds property or municipal taxes. Thus, it was canny of them to resort to exerting indirect pressure on City Hall through the direct pressure they could exert, via pickets and the camp, on the railway companies’ business; and it was lucky for them perhaps that they attracted the politically influential insiders, Rankin and McColl.

Conclusion

As residents of government subsidized, low-income housing on the downtown east side, these women and children of Raymur Place occupied arguably the least desirable place in the social fabric of British Columbian and Vancouver. Their families were part of Vancouver’s “marginal” population, the disenfranchised segment of modern society often depicted as voiceless. Yet the women took up placards, pitched a tent and stared down trains. They acted, and they proved themselves far from voiceless.

In trying to understand the source of their effectiveness, we note that the women couched their demands for safe passage for their children in language of equality: they argued that society’s young are entitled to safety and the care of adults, and that this protection must accrue to all children—it must be universal, inalienable—independent of a child’s economic worth, class status or neighbourhood. They thus tapped into modern liberal notions of human rights, challenging two levels of government head-on with their perception that this fundamental principle of the social contract was being betrayed. Such accusations would have been untenable affronts to a government that genuinely took responsibility for eradicating inequities of circumstance, and for affording all citizens equal dignity and liberty of person.

But this tactic wasn’t enough. As the mothers also recognized, as property-less tenants in low-income rental housing, they could be ignored by those who focused on economic clout, who listened to the property taxpayer rather than to all citizens. To exert economic pressure, the Raymur Project protesters needed additional influence. They became most effective when they trespassed on property, interrupted shipping and held company profits to ransom. They did this not in the spirit of revolution—although certainly their actions were illegal and radical—nor to pursue a radically new or novel direction for society, however narrowly defined (as in perhaps even a change in control over neighbourhood development). Nor were they rebelling, per se, against the rail lines that bordered and thus circumscribed their community. They wanted only safe passage, freedom from harm and danger, for their children. In winning their cause they proved that one can fight city hall, but that it may be best, when doing so, to arm oneself with the government’s own language, vision and values.

*

Meg Stainsby (SFU Graduate Liberal Studies cohort 2000) is currently pursuing a Phd in Creative Writing at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David (Lampeter, Wales). She writes: “This paper was submitted in GLS 814: Liberty and Authority, offered by Dr. Peter Schouls as a study in the philosophy of revolution. The class held its first seminar—ironically, ominously—on the evening of September 11th, 2001. The opening section of the essay has been slightly compressed.” Meg Stainsby and her rag-doll kitten split their time between Vancouver and Salt Spring Island. Editor’s note: Meg Stainsby has contributed previously to The Ormsby Review, Writing My Father (“Stainsby’s Carbons and Files”), a memoir of her father Don Stainsby (1928-1981), the well-known columnist for the Vancouver Sun.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] J. Locke, The Second Treatise of Government. Ed. C.B. Macpherson. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1980), p. 47.

[2] “Civil Disobedience.” Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought. 2nd ed. Ed. A. Bullock. (Glasgow: HarperCollins, 1988), p. 129.

[3] Peter Schouls, “Revolution.” Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Ed. E. Craig. (London: Routledge, 1998), p. 301.

[4] Schouls, p. 301.

[5] Canadian Mortgage and Housing Commission, To Build a Better City. (Vancouver: CMHC, 1966). Video.

[6] L.C. Marsh, Rebuilding a Neighbourhood: Report on a Demonstration Slum-clearance and Urban Rehabilitation Project in a Key Central Area in Vancouver. (Vancouver: UBC, 1950), p. ix. Italics original.

[7] S. Watson, “Art in Living: An Overview, 1946-1959.” Vancouver: Art and Artists 1931-83. (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1983), p. 74.

[8] Watson, p. 75.

[9] Watson, pp. 76-77.

[10] Watson, p. 78.

[11] As quoted in Watson, p. 78.

[12] CMHC video.

[13] September 1967. Photo archive of documents, available at Lord Admiral Seymour School (Vancouver).

[14] P.R.U. Stratton. “Public Housing Experience in Vancouver.” Habitat 3.2(1960): 20–23.

[15] Marsh, p. 21.

[16] Stratton, p. 21.

[17] Stratton, p. 21.

[18] Province, 6 Jan. 1971, p. 2.

[19] Sun, 7 Jan. 1971, p. 1.

[20] Sun, 20 Jan. 1971, p. 25.

[21] Sun, 20 Jan. 1971, p. 25.

[22] Sun, 20 Jan. 1971, p. 25.

[23] Photo archive, 23 March 1971.

[24] Sun, 24 March 1971, p. 3.

[25] Sun, 6 Jan. 1971, p. 2.

[26] Sun, 7 Jan.1971, p. 1.

[27] Photo archive, 23 March 1971.

[28] Sun, 6 Jan. 1971, p. 2.

[29] A. Rose, “The Relationship between Public Housing and Public Welfare.” Habitat 3.2(1959): 2-9.

[30] J. Adams. A Tenant Looks at Public Housing Projects. (Vancouver: United Community Services of the Greater Vancouver Area, 1968), p. 20.

[31] Sun, 7 Jan. 1971, p. 1.

[32] Province, 7 Jan. 1971, p. 6.

[33] Province, 7 Jan. 1971, p. 2.

[34] Sun, 7 Jan. 1971, p. 2.

[35] Sun, 20 Jan. 1971, p. 25.

[36] Province, 7 Jan. 1971, p. 6.

[37] CNR press release. Photo archive, 23 March 1971.

[38] Province, 7 Jan. 1971, p. 6.

[39] Province, 25 March 1971, p. 29.

[40] Province, 24 March 1971, p. 29.

[41] Sun, 7 Jan. 1971, p. 2.

[42] Memo dated 10 March 1971. Photo archive.

[43] Sun, 27 March 1971, p. 13.

2 comments on “1093 The militant mothers of Raymur”

Fascinating. Such history we have lived through, and we’re not done yet. Especially pleased to see that photo at the end, with Joan Morelli in the middle. I remember her and her daughter Karen from St. James parish, when our kids were teens.