1083 Friendiversary

SHORT STORY: Friendiversary

by Jennifer Moss

*

Introduction. This story reimagines a thousand-year-old love affair. Peter Abelard, a philosopher and tutor, fell in love with his student, Heloise. They wrote reams of letters and poetry, and made love in all kinds of scandalous places from convent kitchens to Heloise’s uncle’s house. When they were inevitably caught, Heloise was unrepentant. After giving birth to their child, she was coerced into marrying Abelard, an act which she saw as a step down from the true, spiritual commitment she had already made. Then — her angry uncle sent his henchmen to castrate Abelard (ouch!). Heloise would have stuck it out anyway — but Abelard insisted she go to a convent for her own safety. He then left her there for good. She took religious orders, eventually becoming a respected Abbess, while Abelard evolved into a famous wandering malcontent and critic of the spiritual status quo.

Later in life, they struck up a new correspondence, consisting of letters both hot and philosophical. In this re-telling, I imagine who these characters would be if they were transposed to contemporary Vancouver. How would the torrid affair of their youth play against their more mature occupations? How does Medieval feminism, as exhibited by the strong choices made by Heloise, “play” against 2nd and 3rd wave feminist ideals? What kinds of values would these characters have, and how would those values exhibit in a modern context? In other words, how would we recognize their medieval selves if they were to walk amongst us today? — Jennifer Moss

*

Dull is the Star

Dull is the star, once bright with grace

In my heart’s dark cloud.

Faded is the smile from my face

With no joy endowed.

Justly I grieve,

For though it is near, hidden to me

Is the tender, blossoming tree

To which I cleave.

In love this lovely girl outshines

Every other one.

Her name reflects the beaming lines

Of Helios the sun.

She is the mirror

Of the sky. In her I rejoice.

She is my life. My only choice

Now and forever.

I rue the time, each day, each hour,

Of my solitude,

I who nightly pulsed with power,

With such aptitude

For kissing lips

That breathe with spices when they part,

And from which, to bewitch the heart,

Sweet cassia drips.

She wastes away and is without

Hope of nourishment.

Her youth’s flower withers with drought.

May this banishment

In reparation

Be annulled, and be it guaranteed,

That life together will succeed

This separation.

— Peter Abelard, “Dull is the Star”[1]

*

Heloise Garlande stared out the window of her office at the University of British Columbia. She was up on the 10th floor of the Buchanan Tower, above the tree canopy. She could usually see the North Shore mountains from here, but not today. Though it was morning, the streetlights were still on, and low clouds hung over the landscape. It was snowing again, this time in earnest, which was fine by her. Heloise loved the snow, the way it cleaned everything up, making the landscape look monochromatic, less cluttered, more deliberate. How nice it would be if things really were that black and white.

Environment Canada had issued a weather warning for what the rest of the country called, “a couple centimetres of snow.” But in hilly Vancouver, even a dusting wreaked havoc on the roads. The university had officially declared a snow day, which meant there were hardly any students at school. The busses weren’t running, as only vehicles with 4-wheel drive could make it up the long hill to the campus. Small groups of first years scuttled by with determined looks on their faces, clutching their re-usable coffee mugs as they braved the elements between their residence buildings and Starbucks. A snow day. Heloise remembered what that had meant back when she was a student. Released of all responsibility, forced by the weather itself to sleep in, you might stay home and snuggle under a blanket, or maybe bundle up and go for a walk in the cold. That sense of freedom, of stolen time. Beautiful. How long had it been since she’d had that feeling?

Heloise sighed. No rest for the tenured. The pressure to make her deadlines far outweighed the snow’s magic. It had been a rough start to the term and she was far behind in her correspondence. If the snow offered her any gift, it was simply the reprieve from having to lecture; the time to clear out old emails and actually finish a thought. As the newly appointed Chair of Gender and Women’s Studies, she was under a lot of strain. The last person to do the job had run off with a grad student leaving behind a colourful miasma of controversy. As a result, all her decisions were closely scrutinized by committee. And while she understood the reasons for such caution, she hated it. She felt hobbled. Nothing was to be done if it could not be done strictly by the book, which meant that almost nothing got done at all. Heloise was halfway through yet another memo on the new campus sexual assault policy. She was finding it totally impenetrable, which was no doubt intent of its authors.

Restless, she decided to take a quick peek at Facebook. She did so with no small amount of shame, knowing what she knew about privacy, internet predators, and corporate agendas. Her students had long since migrated to Discord and Instagram. They said Facebook’s days were numbered and she believed them, mostly. Then again, it was one of the only ways she kept in touch with her family back in France. Her mother constantly posted photos of life in the village outside Paris where Heloise had grown up. These days, it was really more of a suburb. But she liked seeing the neighbours’ latest kitchen renos, or pictures of her sister’s growing family. Heloise sighed again. Her sister Marie had married a local car salesman, and they’d bought an old farmhouse on his earnings, neither of their parents being of much help, financially. They’d just had their third child, a girl. Heloise had been abroad for many years, so she could no longer be sure of anything happening back home. But Marie certainly seemed happy being a stay-at-home mom. At least, she looked it in the pictures. She and her husband appeared to have lots of friends. They celebrated every anniversary and Valentine’s Day with what appeared to be an uncomplicated enthusiasm, grinning at the camera in various restaurants, posing good-naturedly over plates of boeuf bourguignon. For weekend entertainment, as far as Heloise could tell, they packed up the kids and drove around to antique car shows. There was shot after shot of their one-year-old son, Remy, at the wheel of different classic cars. Today, there was one of the little boy waving from the window of a dark green 1959 Facel Vega HK500. His mop of soft, blonde curly hair reminded her of her own son at that age. She wondered if her sister knew that was the same kind of car Albert Camus had died in. She doubted it. Marie had never been one for the existentialists.

Heloise rubbed her eyes. How long had she been staring at the screen? Too long. She was turning into one of her more zombified students, getting sucked into social media, and wasting valuable time. The light in her office had shifted, and outside, the snow was easing up. It was supposed to turn to rain by tomorrow. Not much of a prediction, really, since snow never lasted here. Scrolling down, she noticed her friend in Toronto, right on cue, had re-posted the Beaverton headline, “Disaster in Vancouver – 3 Inches of Snow Causes Real-estate Freeze.” Ha-ha. Just as Heloise was about to close Facebook in disgust, a new post caught her eye. She squinted at the screen, and for a moment she couldn’t breathe. What she saw made the room feel suddenly smaller. There, looking out at her from an incongruous cartoon igloo graphic, was the face of her ex-husband, Peter Abelard. In spite of everything, she had never un-friended him. He never posted, so she hadn’t felt the need. Thinking about him was something she tried hard not to do, but lately she’d been catching herself at it. How odd that this reminder of him would show up today, out of the blue.

As they had never actually divorced, technically, Peter was still her husband. Divorce was far too pedestrian for a man like him. But Facebook had no understanding of such subtleties of character. That’s why right now, right here in front of her, was one of those ridiculous “Friendiversary” videos. An algorithmic distortion of their tumultuous relationship that Facebook, in its wisdom, had blithely assigned to the category of “Friendship.” It read:

Here’s to Nine Years of Friendship on Facebook!

Heloise couldn’t resist playing it, and then playing it again, right away. The random images, trite animation, it was all terribly manipulative but still — she couldn’t stop looking at Peter’s mischievous eyes beaming out at her. The video featured the words to a song he’d once written for her called “Dull is the Star.” It was all about two lovers who couldn’t be together. Very romantic, and as it turned out, quite prophetic. Annoyingly, her eyes welled up. She hated that. Pseudo-emotional social media crap. Despite her ability to instantly deconstruct it, goddammit, it worked. Heloise blinked furiously, holding back tears. Honestly. What if somebody came in and found her bawling like an undergrad? She closed Facebook like she meant it. Bloody Peter. How like him to just pop up like that. Then again, she had heard rumours he’d crawled out of the woodwork. After nine years of complete radio silence, he’d washed up about a month ago at his parents’ place for dinner. Her mother-in-law had written to her about it, rather guiltily, saying that he’d “surprised them with a visit.” Some surprise that must’ve been. She tried to picture him, just waltzing into their sitting room after his extended disappearing act. Apparently, he’d been in India the whole time, except for a brief stint in Berlin where he’d tried to sell solar panels. Trust Peter to bank on the sun in one of the greyest cities on earth. He’d never been a practical man. True to form, after spending a couple of days with his aging parents in Brittany, he’d moved on again, saying he had “other opportunities” to pursue. Nobody asked what kind of opportunities, and nobody had heard from him since. So, it was back to business as usual, the only difference being that this time, he’d left a forwarding email address, which her mother-in-law had passed along to her. She hesitated a moment. She knew what she wanted to do — but, was it wise?

“Fuck it.”

Heloise took a deep breath, and logged onto Gmail.

From: Heloise < lonepine@gmail.com >

Hey there Peter Abelard, you elusive ghost, you.

It’s me, the proverbial blast from your past. So… I wasn’t sure I’d ever speak to you again. But then just today I got one of those “9 years ago on Facebook” reminder notifications. You know those things? Normally I ignore them, but in this case, it was the lyrics to Dull is the Star. One of our songs, remember? Anyway, I thought of you playing your guitar and singing that song to me. Lately I’ve been thinking back on those days quite a lot, and sort of wishing I could turn back time. Does that ever happen to you? “Dull is the star once bright with grace.” No kidding. I work on a campus, surrounded by peoples’ children. I feel about a hundred years old these days. I guess I just hope that you’re well. That you’re cherished by someone, and that you’re happy.

Yours always,

Heloise.

“We have become the men who we wanted to marry”— Gloria Steinem.

Heloise pressed “send,” wondering only briefly what Abelard would make of the Steinem reference in her email signature.

*

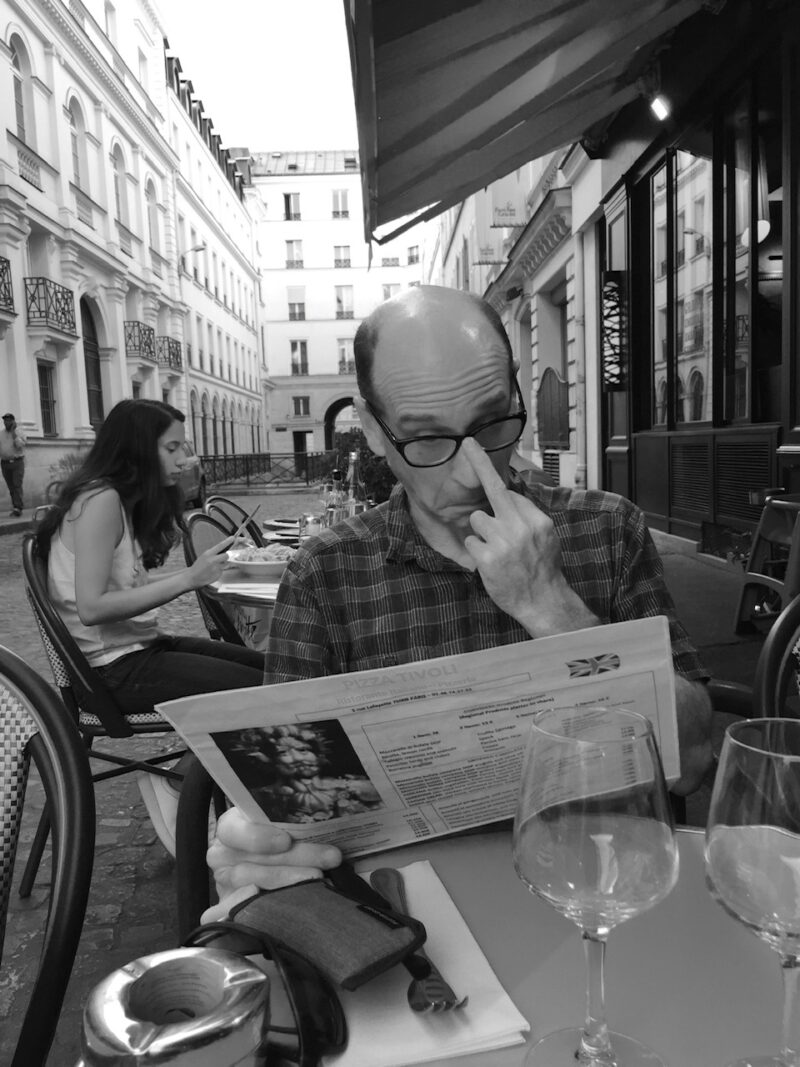

Peter Abelard sat in a plastic chair, tipped back against the wall of the men’s dorm at Tassajara mountain Zen Center. It was a cold, early morning in California’s Ventana wilderness. The mountain retreat was hushed, a skimming of snow on the ground, and Peter could see his breath. The gravel road into the place had washed out two nights ago, so there were fewer short-term guests than usual tiptoeing their way to the hot spring. From his perch, he could see some of the monks gathering outside the kitchen before the breakfast bell, probably concerned that last night’s food delivery truck hadn’t made it. Couldn’t get up the hill, no doubt. But he wasn’t worried. They’d been cut off before and would be again. One of the reasons he’d chosen this place was for its relative isolation. A steep, 14-mile gravel road full of switchbacks and blind corners helped keep the riff-raff away. That and the waiver the monks made you sign.

He picked up his guitar and strummed a few bars, a gentle chord progression that seemed to suit the morning. It didn’t add up to all that much… meandering and slow, like his life most days now, and like the clouds he was watching over the crest of the nearby ridge. Just then a senior monk came walking up the trail. Hearing Peter’s quiet strumming he put his finger to his lips. They were supposed to be in silence all this week. Some Buddhist communities interpreted this rule to mean simply, “no talking” but the monks here were adamant that all forms of distraction, including music, were on the naughty list. Peter nodded at the monk, and put his instrument away. In the past, he would have argued the semantics of silence, but he’d learned to keep his trap shut.

His butt was getting cold though, so he got up and walked towards the woodpile, thinking maybe a little physical work would warm him up. Funnily enough, the same senior monks who frowned on reading or playing music during silent retreat made an exception for wood chopping. He supposed they needed to stay warm, like everyone else. Reaching the woodpile, Peter grabbed the small axe and carefully placed a thick round of knotty ponderosa pine on the chopping block. The wood was fresh, and smelled like the mountains. He balanced it lightly with two fingers so as not to get pitch all over his hand, raised the axe above his head, and brought it down. The piece split evenly with a satisfying “crack.” He let the smaller pieces lie where they fell, picked up another round, this time sycamore. Heave, crack. And another. Heave, crack. He started to get a nice rhythm going, enjoying the mindful-mindlessness of it. It was a form of meditation that worked well for him, better than sitting with his legs crossed, anyway. He often wondered if he would have stayed with the Catholic faith if they’d acknowledged woodchopping and water carrying as legitimate forms of prayer. Anyhow, the monks here at Tassajara certainly had no problem with it. They’d let him stay longer than the usual novice because he got a lot of work done around the place. It was the off-season, and there were fewer Buddhist tourists around than usual, so they were probably just glad for the help. The intense schedule and atmosphere of a traditional Zen Ango, or Practice Period, wasn’t for everyone. A lot of visitors couldn’t hack the monotony of the chores for that long. But Peter had spent years working off his room and board in various communities and hermitages, and had developed quite a knack for chopping wood. If you really paid attention, wood-splitting contained everything you needed. The balance of two oppositional forces: stillness and motion. Calm and violence. Reason, and passion. A metaphor for life itself. It was the closest he got to peace. Heave, crack. Heave crack. Heave… thump.

Peter paused, his rhythm broken by a knotted piece of pine that had grabbed the axe and wouldn’t let go. He tried bashing through it, lifting the axe up, wood and all, and bringing it down with force. It was a tactic that usually worked, but this stubborn piece just wouldn’t split. He reached down to try and pry it apart with his hand, managing to pull the axe out in the process. But as he went to let go, his right thumb got pinched in the crack left by the axe. Instinctively he ripped his hand back. Big mistake. A large chunk of the fleshy part of his thumb stayed lodged inside the wood. Peter clutched his hand, staring dumbly. Blood was pouring everywhere, peppering the snow on the ground around the chopping block. It hurt like a beast. “Jesus Christ!” Peter bellowed at the top of his lungs. So much for silent retreat.

Inhaling sharply, Heloise looked away from her screen, and back at the growing snowstorm outside. Thick, white flakes fell with the slow air of ballerinas warming up, landing with unhurried ease on the concrete courtyard below. She felt lonely. The photo of her sister’s son had only succeeded in reminding her how far from home she really was. Then again, even if they lived in the same village, she and Marie would still be worlds apart. It was sometimes hard to understand how they could be from the same family. Heloise was the eldest, and edgiest. “The burnt crepe,” her mother would say. More intense than Marie, she’d excelled at school, beating all the boys at spelling. She’d even won a regional prize for public speaking in fifth grade. Then one day, right after her 13th birthday, her classroom teacher insisted on walking her home after school. She’d thought she was in trouble, and in a way, she was. Sitting at their kitchen table, her teacher told her parents she was “academically gifted” and should receive “more focused instruction than the local school could offer.” The way he said “academically gifted,” had made Heloise, eavesdropping from around the corner, think he was talking about a disease.

“She requires special treatment. It would be a waste if she didn’t pursue her studies at a higher level,” her teacher had said with his mouth full, the crumbs of her mother’s coffee cake all down the front of his sweater. Her parents had never completed high school and were generally suspicious of educators, but that day, they took her teacher’s advice without question. They’d always known their eldest daughter was different.

Despite Heloise’s pleading – for she had begged to be allowed to stay — she was sent away. Within the month, she was packed off to Paris to live with her Uncle Fulbert, a deeply religious man who breathed loudly through his mouth and had skin allergies. She was enrolled right away in a large, established school, where she began an in-depth study of European history, and was introduced to both Latin and Greek. Heloise hated to admit it, but she supposed her teacher had been right. Paris was the place where she began to embrace her inner nerd. Her mind flourished there, as she was finally able to learn amongst students who were as dedicated as she was.

As a guardian, Fulbert was kind, but strict. A dedicated student of biblical text, he encouraged her to develop her spirituality. Although it was all new to her, she soon began to love the stories of ancient kings and peasants, the moral conundrums and beautiful, symbolic language. Her uncle was good to her. She was relatively happy, though it was a very male household, and she missed her mother. She remembered taking an immediate dislike to Fulbert’s son, her cousin Anselme, who had shown no aptitude for scholarship and was rumoured to move in “bad circles.” He no longer lived at home, thankfully, but he’d show up occasionally to do laundry and wolf down Sunday dinners. Whenever her uncle was out of the room, he teased her about her changing body. Once, when she was around sixteen, Anselme told her uncle he’d seen her “flirting with boys on the road after school.” It wasn’t true, of course. Or if it was, it had been harmless. At that time, Heloise thought, she had been quite literally as pure as the new snow now amassing below her office window. But Anselme’s comment was just enough to make Uncle Fulbert look at her differently, somehow. She felt it almost immediately. A few days later, when she was getting dressed, her uncle opened her bedroom door without warning and hovered there, scratching his eczema, while she awkwardly rushed to pull her school uniform down over her head. “We have to get you out of that school” he said, and then shut the door abruptly. She would never forget the feeling of shame that flooded her body at that moment. As an educated adult, Heloise recognized Fulbert’s patriarchal reaction for what it was. Her uncle, alarmed at signs of her womanhood, had sought to clamp down on her for reasons that ranged from wanting to protect her, to wanting to keep her for himself. But as a young, Catholic girl in France, a teenager, she’d felt only guilt at the time, as though she had done something dirty.

Fulbert had announced at the breakfast table the very next day that Heloise would no longer be attending classes. He said she was “extremely lucky,” and that instead, she was going to be tutored by a “leading scholar,” someone who had come up through the Catholic University near Notre Dame de Paris. His name was Peter Abelard and, her uncle assured her, he was a renowned lecturer on theology. “A rising star,” her uncle said. Apparently, this Abelard had agreed to tutor her in Latin and Greek at a reduced rate in exchange for room and board. Heloise recalled how pleased with himself Uncle Fulbert had seemed. He thought he’d found the perfect solution — a way to continue her classical studies without exposing her to corrupting influences. It was his idea that if she stayed close to home, she was less likely to be distracted by the boys her own age, who her uncle said only had “one thing” on their minds. Embarrassed that he would even bring up that “one thing” in her presence, Heloise had quickly agreed to the new arrangement. What else could she do? If she fought back, she’d be deemed morally suspect. Secretly though, she’d been angry that she was to be cut off from her peers. That is, she felt angry right up until the moment when Peter Abelard himself appeared on her doorstep.

Her uncle was out, and the maid had the day off, so Heloise had answered the door absent-mindedly. And there he stood, this impossibly good-looking young man. Dark curly hair, crisp white shirt and jeans. He carried a guitar, and a leather book bag, bursting with heavy books, which he shifted to his hip as he stuck out his hand and introduced himself.

“I’m Abelard. But you can call me Peter.” Heloise had tentatively reached out to shake his hand. The shock was instant. She’d felt it resonate through her whole body, in places she hadn’t known had nerve endings.

“I’m Heloise.”

“Oh… I know who you are.” He casually placed his book bag down and looked around at the entrance hall. “Are you home alone?”

“Yes, uh, my uncle is out for the afternoon,” she’d stammered.

“Good,” grinned Abelard. “Then we’ll have some time to sit and talk. Would you mind showing me to my room so I can put my stuff away?”

Heloise had nodded, and asked him to follow her. She remembered clearly how, as they climbed the stairs to the wing of the house where he was to be boarded, she could feel his eyes watching her body. But instead of feeling uncomfortable like she did when her cousin was around, this time it felt good. She’d arched her back ever so slightly, and Peter, fumbling, had dropped a book. At the top of the narrow staircase, Heloise opened the door to his bedroom, and paused in the doorway, her back now pressed against the door frame, so he could squeeze past her. As he did so, she caught her breath. For he did not rush, or look away, or seem embarrassed that they stood so close, facing one another, the fronts of their bodies practically touching. In fact, quite the opposite. He lingered just for a moment, and smiled, before pushing past her. “Excuse me.” She had met his eyes without flinching, and in that moment, they both knew what would happen.

“You’ve got blood poisoning,” said the doctor. “I’ve ordered several rounds of IV antibiotics and we want to keep an eye on you.” Peter nodded. He’d figured as much from the red streaks running up his arm. He knew from a previous injury, years ago, that those streaks were bad news. The monks had fixed his thumb up as best they could at the centre’s first aid station. They’d stopped the bleeding but then clotting and infection had set in. After a day or so, he’d developed a fever, and the monks got worried. The road remained closed due to washout for several days, so Peter was relegated to the infirmary, where he was fed a diet of vegetable broth. Despite the fact that he’d signed a waiver, none of the monks were keen for him to die on their watch. So as soon as the road cleared, the acting shuso, the head monk of the retreat no less, personally drove him to the hospital in the centre’s beat-up old Land Rover. The shuso stayed to see Peter admitted, but then, needing to hit Costco on the way back before traffic got bad, he’d bowed politely, leaving him alone in his hospital bed.

“Want to watch TV?” asked a young nurse, bustling into the room. Peter couldn’t help but notice she had extremely well-developed calf muscles.

“No thanks. Hey, are you a cyclist?” The woman turned, saw him staring.

“I bike to work,” she said carefully, going about the business of hooking up his IV.

“Every day?” he asked, just to keep the conversation going, to hear the warmth of a human voice through his fog of pain.

“When I can. You sure about the TV?”

“Yeah – but can I get wifi in here?” She leaned over his bed, neatly flicking the IV tube with her fingers, smelling of antiseptic, sweat, and something else. Maple syrup? How long since he had been this close to a woman?

“You can – but you gotta pay for it.”

“Never mind.”

“You got insurance?” she asked casually, eyeing his dirty old hiking boots in the corner of the room, “cause they’ll want to know your details at some point.”

“Not exactly,” he admitted.

“Well is there someone you can contact?”

“Maybe, but only if you tell me the wifi password.”

The nurse laughed, giving him one of those, “you’re incorrigible” looks that women give, right before they do what you ask them to. Then she whispered the password to him, and left the room. Peter leaned back in his hospital gown, pleased with himself. He still had it.

When the coast was clear, Peter took out his phone with his unbandaged hand, and it was only then that he saw Heloise’s email. He read, and re-read it, several times. He wrote three different responses: the first, when the narcotics were strongest, begging her to come to him right away and kiss his thumb better, the second containing a short critique of Steinem’s second-wave feminism from an intersectional perspective, before finally settling on the one that seemed best, under the circumstances.

From: P. Abelard: < steadynow@hotmail.com >

Dear Heloise, my one-time wife,

Thank you for your recent note. I am doing well, and I trust you are too. I wish you all the best in your future endeavours.

Sincerely, P.

“Do not pray for easy lives. Pray to be stronger men.”— JFK

He couldn’t be sure, but he hoped that would settle it. Best to nip these things in the bud, after all. But then he heard a ping. Without waiting, she had answered him. Cautiously, he opened the email and read:

From Heloise: < lonepine@gmail.com >

To Peter, a.k.a. Numb-nuts;

Seriously? That’s all you’ve got? Is this some kind of joke? After all we went through? Me getting pregnant and kicked out of my house? Me having our child, and having to leave him with relatives so I could earn a living? You disappearing off the face of the earth to go “find yourself” or whatever it was you were doing in India? I finally get the courage to reach out to you across the great divide. I’m like full-on Adele here, “Hello from the other Side” and you blow me off with a note like you probably send your accountant at Christmas? I’m sorry, no. I don’t think so. You don’t get to be dismissive of me. If anyone’s going to be doing the dismissing – it should be me! Your son is fine, by the way. Thanks for asking. Asshole.

Heloise.

“We have become the men who we wanted to marry” — Gloria Steinem

Furious, Heloise descended the stairs from her office, pulling on her mitts and scarf. She hadn’t gotten any work done, yet she already needed a break. The Abelard Effect. She didn’t know what she’d been expecting – certainly not an immediate answer. And yet it was just like him. He never did anything expected. Peter was one of those men who never questioned his own right to act in whatever way he chose. He was smart, but in constant conflict with authority. When he taught at the university in Paris, he’d run circles around the older professors. It made sense to her now. He came from a wealthy background, a white, only child. Why wouldn’t he say whatever he pleased? Still, she had to admit his confidence was part of what had made him attractive to her in the first place. When she thought of the first day she met Peter, Heloise couldn’t help smiling, which was infuriating. It occurred to her that yes, she had been innocent, alright. But not that innocent. As a Women’s Studies professor, one of her pet peeves was the way other scholars, mostly men, infantilised and victimised young women who happened to be virgins, as though one’s entire sexuality totally shifted due to the mechanical act of penetration. She had known the power she held over Peter from the moment she set eyes on him. He hadn’t stood a chance. She was no victim.

Stomping through the snow, Heloise considered how even the word “virgin” annoyed her. Depending where you looked, etymologically- speaking, the word either meant, “someone who has never engaged in sexual intercourse” or, “someone who is sexually inexperienced.” The space between those two definitions left a lot of exposed ground. So much ground as to make the word practically meaningless. By one interpretation, having sex just once would be enough to bump you up – or possibly down — to a whole new category. But by the other definition, you could be relegated to the virginal ranks of “sexually inexperienced” indefinitely, until somebody declared you to be “no longer virginal.” Under this definition, how many times would be enough for you to graduate to non-virgin status? Maybe that was what Lionel Ritchie was on about when he sang, “Once, twice, three times a lady.” She’d often thought maybe virginity should just “re-set” after a long dry spell. It was a ridiculous concept anyway, so why not? Leaving the question of her virginity aside, there was no doubt that her tumultuous relationship with Peter Abelard was at least partly her idea, and that the man had had a profound effect on her development. He’d taught her a lot, both intentionally and unintentionally. Mostly, he taught her to be intellectually rigorous. Heloise had spent years deconstructing her Catholicism, and concluded – like many before her — that the whole virgin mother thing was a hastily concocted cover-story. Clearly, Mary had either been raped, or perhaps she’d had a hot tutor as well. For her PhD thesis Heloise had waded into the whole virgin birth myth, looking at its effect on Christian beliefs. There were, she’d discovered, rumours originating from Greek texts that a handsome Roman soldier named Pandera had been close to Mary. Subsequent rabbinic texts had apparently referred to Christ as “Jesus ben Pandera,” which was definitely not meant as a compliment, the implication being that he was a low-born bastard. So, out of some kind of insecurity in the face of such insults, the early Christian church came up with the virgin birth plot as a cover story. It was a total red herring, and in her paper she had argued that it was not at all in keeping with the true spirit of a religion whose central figure liked to mingle with lepers and prostitutes. Christ had been all about tearing down the distinction between the pure and the impure. “History has obsessed over Mary’s supposed purity instead of her actual personality,” she had written in her dissertation, “and that misdirection has affected attitudes towards sex and femininity in a way that is harmful to women.” Heloise herself, still a Catholic at heart, looked up to the real Mary, a young woman who, pregnant, unmarried, and couch surfing at a friend’s place, had sung defiant songs about how God, “brought down rulers from their thrones but lifted up the humble.”

After walking for some time, Heloise found herself at the entrance to the Nitobe Japanese Garden, way over on the west side of the campus. It was freezing cold and the gardens were closed on account of the snow. Peering through the gate, she thought it looked more beautiful than usual, covered in this even blanket of white. Undisturbed, as if a team of fastidious Japanese gardeners had carefully raked the whole place. Her heart rate slowed somewhat. She guessed the initial shock of hearing from Peter was abating. He was an asshole, it was true, but she realized she owed him a lot. After all, it was Peter who had first gotten her to consider Mary’s true nature. Peter who had opened her eyes to so many things. She’d fallen for him in every way that it is possible to fall. In love, in lust, in sickness and in health, she had been his. She’d given over to him in a way that only a young woman can, with total generosity, total commitment, and no thought for how she might get hurt.

They’d begun their physical relationship soon after he moved into her uncle’s house. It was shockingly easy to deceive the old man, claiming to be devoted to her studies, insisting on closing the door to “prevent the household noise from entering the classroom,” when really it was to prevent the sound of her orgasms from echoing down the stone hallways and out onto the street. But it wasn’t just the sex, at least not for her. Peter was unabashedly romantic. He was a musician. He performed at local coffee shops, and would dedicate songs to her. Sometimes he even used her name in them: “In love this lovely girl outshines every other one. Her name reflects the beaming lines of Helios the sun.” Every girl should have at least one song written about her, he’d said. And even though she and Peter lived under the same roof, he would write her old-fashioned love letters. “Let me turn from the light of the sky and gaze without end at you alone.” It all seemed a bit cringe-worthy in hindsight, but as a young woman, she’d lapped it up, no questions asked. Peter had helped her begin to see her own worth. More than that, he’d made her confident in her own academic power. They truly did spend many hours discussing and arguing the big ideas of life, in both Latin and Greek. Of course, they also used these venerable tongues as their private love language. At the dinner table Peter would say things like, “Non possum off oculos tuos ubera,” which, translated literally, meant “I can’t take my eyes off your breasts.” Her uncle, who only pretended to know Latin, had simply gone on forking his pomme-de-terres, pleased to see that his niece’s skills were developing.

It had gone on for several months this way, and every which way, until one night her cousin Anselme came to dinner. It was spring, and Heloise had an early plum blossom tucked in her hair. She and Peter had just finished a rather epic study session, focusing on Euripides’ tale of unbridled passion, The Bacchae, and involving some very compelling role-play. She had unfortunately forgotten to refasten her top button. Anselme remarked on it, and something about her response he deemed too casual, too uncaring. She remembered his ratty face, squinting at her. He knew.

“You don’t seem too bothered that you look like a slut.”

The word was like a slap in the face. Peter had gripped the edge of the table and half stood up, making as if to say something. But she calmly did up her button. “I’m sorry?” “You heard me. You shouldn’t go around like that. Not with Abelard living here.” He glared at Peter. “What kind of dog are you?” Her uncle, rousing from his wine-induced torpor, had looked up then, and said something appeasing about Abelard being “the soul of trustworthiness.” “Is that right?” spat her cousin, his eyes never leaving Heloise’s top button. “Have you seen the way he looks at her?” Uncle Fulbert shook his head, as if rejecting the very idea, but the damage was done. From then on, they were watched much more closely. It became difficult to carry on in the house the way they had before. Her uncle took to popping his head in with the excuse of asking questions during their study times. Once, he nearly caught them in the act, but Abelard pretended they were re-enacting Leda and the Swan. After that, they looked for places where they could make love undisturbed. Quiet groves in parks, down in the wine cellar of a local restaurant, or after closing time in the back of a shop that sold scientific instruments, where Abelard bribed the owner to give him a key. Once, memorably, they did it in a small ante-chamber at Notre Dame de Paris, after all the tourists had gone home. It was beautiful. She had definitely heard the angels singing that time. Looking back, she was amazed at their audacity. Her cousin and uncle, despite not being the brightest of men, grew increasingly suspicious. However, without proof there was little they could do. And then, one day there was proof, in the form of a missed period. Always regular as a digital alarm clock, Heloise knew right away that she was pregnant. Terrified and proud at the same time, she paced her room all day, waiting for Peter to come home from the university. She was nervous to tell him, but when she did, he’d seemed excited and happy. He hugged her and stroked her hair, and said teasingly, “We should call him Astrolabe, after the shop where he was conceived.” She’d laughed, “Or why not Sextant?” A few weeks after this discovery, Heloise had packed a small bag. Peter told her uncle they were going to the library, but instead they bundled into a car and drove south towards Brittany, where Peter’s parents lived. On the way there, they stopped at an inn where, pretending to be married, they took a room for a night. Heloise still looked back on that time whenever she needed… inspiration. To be sleeping together in a soft bed, with no fear of discovery, it brought a new depth to their lovemaking. Or perhaps it was the pregnancy hormones that made her brave, and willing to try new things. In the morning, after a hearty breakfast from the friendly innkeepers — who if they doubted their story did not let on — they got back on the road and drove to Le Pallet, to the country estate where Peter had grown up. Remembering how in love they used to be, Heloise, for the second time that day, fought the urge to cry. The wind was stung her face, and her lips felt chapped. Her phone beeped. Glad for the distraction, she took off her mitts to swipe it. Another email notification.

From: P. Abelard: < steadynow@hotmail.com >

Dear Heloise, “Purveyor of Harsh Truths”

Hey. I’m very sorry to have made you mad. Really. Your email caught me by surprise is all, and I wasn’t sure how to respond. Honestly, I’m not used to receiving attention from women these days. I’ve been living with a community of Zen monks in California. Chopping wood, carrying water, that kind of thing. I only check my email when we go into town.

Sincerely,

P.

PS – And of course I’m very glad to heard that Astrolabe is well. I meditate on him, and on you, often.

“Do not pray for easy lives. Pray to be stronger men” — JFK

*

From: Heloise < lonepine@gmail.com >

Dear Peter – “Ignorer of basic facts.”

Seriously? A community of Zen monks? Well maybe you’re not a total asshole then, I guess. So, like, does this mean you’re celibate? Because frankly I find that hard to imagine. Far be it from me to distract you, but as I recall you used to be fairly easy to distract. Do you remember that time we tried spanking? At that little inn on the way to Brittany? I’ve never forgotten it. I’m literally the Chair of the Gender and Women’s Studies Department at my university, and all I can think about right now is how badly I wanted you to hit me that day. How good it felt when you did – how much I trusted you. Too bad you can’t meditate away your past, hey?

Heloise.

“We have become the men who we wanted to marry.” — Gloria Steinem.

Reading over her email, Heloise was shocked at herself. She felt like a different person. Someone who told the truth. It was liberating. All these years she’d wanted to confront Peter but been unable to. Now finally – instigated by a ridiculous Facebook message — like a springtime iceberg she was sloughing off years of frustration, loneliness, and sexual longing. Peter probably thought she was nuts. She didn’t care. She hadn’t felt this brazen in a long time.

It had been quite late at night when they’d pulled up to his parents’ house, a large white mansion with an imposing circular driveway lined by persimmon trees covered in small green fruits. It all seemed very exotic to Heloise. They’d gotten out of the car, each shouldering an overnight bag, and stood holding hands before knocking. Peter’s father, a retired Lieutenant-Colonel, opened the front door himself.

“Got your message. This her, then?”

“Heloise. Nice to meet you.” She stuck her hand out, but the older man did not reciprocate. At that moment, Peter’s mother pushed in front of him.

“Heloise, it’s so nice to finally meet you. Peter’s told us so much about you. Come in, come in. You must be tired after all that driving.”

And with this thoroughly mixed welcome, Heloise had stepped over the threshold of her new, temporary home. She was whisked into the stiff and formal living room, where she was offered a soda water while everyone else downed red wine, hoping it might cure the awkwardness in the room. It didn’t. Still, it was here she would stay in the weeks and months before the baby came, walking the paths in the walled garden, keeping away from the local shops so the gossips wouldn’t get a look at her condition, waiting.

Peter’s father mostly ignored her, and his mother treated her like a project, advising her on everything from a healthy pregnancy diet to the appropriate amount of exercise. During the week, while Peter was up in Paris lecturing, she would eat silent dinners with his parents, where she was afraid to even ask for the salt. “Bad for your blood pressure, you know dear,” her mother in law would say, mildly, but still with the expectation of being obeyed.

On weekends when Peter finally drove down, they had to stay in separate rooms, while she grew larger and larger. One day, looking out her bedroom window, she saw her uncle’s car pulling up the gravel driveway. Fulbert and Anselme got out and marched towards the door, looking serious. Luckily, Peter was out, so confrontation was avoided. Instead her uncle had a long talk with Peter’s father in his study. When it was over, they called her downstairs. By this time, she was really showing, and when her cousin saw her he looked shocked, and stared at the ground. Heloise stood up a little straighter. Let him stare.

“The Lieutenant-Colonel and I have had a talk.” Uncle Fulbert’s jaw was a rod of steel. “It’s quite a mess you’ve made, and it needs to be cleaned up. We think you and Abelard should get married.”

“I’ve arranged it for next week.” Peter’s father spoke with a finality that nobody would dare to question.

“I hope you can fit into your wedding dress,” smirked her toad of a cousin.

“What does it matter now?” Fulbert turned to leave, scratching his elbow, his shoulders slumped. At that moment, Heloise felt sorry for him. Sorry for going behind his back, sorry for disappointing him. Just sorry. After all, he had done his best with her, having never had a daughter of his own. It wasn’t his fault he was incompetent.

That was it, thought Heloise, tromping through the snow. That had been the moment when all her regrets had started. Until then, she had been in a dream, knowing nothing and needing nothing other than Peter. But when she’d seen her uncle’s defeated retreat, and the grim look on Peter’s father’s face, she’d begun to understand the complexity of the situation she and Peter had put them all in. Her uncle was a prominent member of his church. Peter’s father was a leader in his community. She’d realised at that moment that these people who were sheltering her were also ashamed of her. It was unfair, but there it was.

Peter had agreed without hesitation to be married, but Heloise fought back. She didn’t like the terms. What kind of marriage would they have if it was forced on them? How would they know, when things got tough, if they were really meant to be married? She didn’t reject Peter. Just the idea of marriage under duress. Of course, he had talked her into it anyhow. He had always been able to convince her of things. Peter thought marriage would get the relatives off their backs, and for a while it did. They’d tied the knot just before closing time at the local municipal office, with Peter’s parents and her uncle as witnesses. It was about as far from a proper Catholic wedding as it was possible to get. She could close her eyes, even now, and picture their glowering faces. The bored, obsequious Justice of the Peace, the plastic-y beige furniture. She could almost hear the scrape of the cheap pen she’d used to sign the registry.

When her labour started, Peter was in Paris, working. They were trying to save up to rent a little apartment. Feeling ill at the dinner table, she’d made an excuse to his parents, stood up with some difficulty, and then noticed a puddle on the floor under her feet. The maid had rushed in with a towel, and Peter’s mother had helped her upstairs to bed. She remembered feeling mortified while Peter’s father kept right on sipping his wine as though nothing unusual whatsoever was happening. Meanwhile, Heloise’s universe was splitting open. Pains were shooting through her body every few minutes, strong enough to make her throw back her head and groan in pain.

“Shhh – shh,” her mother-in-law had whispered, probably concerned about the neighbours. But Heloise could no more control her voice than control the process happening in her belly. She lay helpless on her bed while her body, which had lately become a stranger to her, underwent its terrible transformation. A doctor was summoned. He told her to lie on her back, which she did until the pain became unbearable. She then flipped onto all fours and threw her head back, screaming, “leave me alone, all of you!”

Hours passed. It got dark outside. The doctor looked in, mumbled something, and left again. Her mother-in-law lit a candle, and Heloise stared at the flame intently, seeing worlds inside it. People came and went all night, checking on her, but Heloise barely noticed. She felt utterly alone. Without Peter there, she was in exile on a faraway planet, locked in an intricate cosmic dance, with no knowledge or understanding of the steps. She cried out in desperation, feeling that she couldn’t make it back… that she would never be able to do it, that perhaps this child was trying to kill her from the inside out. But when the candle finally burned down, and light began to break in the east, Heloise grew quiet. Her breathing changed, and she bore down.

“Astrolabe?” her mother-in-law had said, in her saccharine way. “Really? How… scientific.”

“Peter chose the name,” Heloise replied, hoping that would be the end of it. Of course, it wasn’t.

“The poor kid will never live it down,” said her father-in-law when, after the blood had been cleaned up and order restored, he dared to poke his head in to see his grandson. At the time his comment had rankled her. Now she saw that he had been right. Astrolabe. What were they thinking? An astrolabe was an instrument used back in Medieval times to measure the altitudes of celestial bodies. She supposed that she and Peter had been like celestial bodies when they’d come up with the name. Peter, at least, had probably been high. He was always partial to weed. Said it made him see “universal truths,” made him hear melodies, and made him better at lovemaking. Who was she to argue?

But Astrolabe, despite his auspicious name, proved a challenging infant. All babies cry, but he cried more than most. Non-stop, in fact. The term the doctor used was “purple crying,” she supposed due to the deep shade of purple he would turn, like a Norwegian on holiday in Mexico, wailing as if he was being castrated, or perhaps boiled alive in oil. He cried all day and most of every night. The only time he stopped crying was when he was in a moving stroller. During the week, conscious that his screaming was setting Peter’s father’s teeth on edge, Heloise would drag her tired body out on walks, pushing Astrolabe up and down the block, endlessly, trying to get him to sleep. He would fool her into thinking he was unconscious, but as soon as she stopped wheeling the stroller and ventured to sit down on a park bench, he’d start up again, worse than before. She remembered the way he’d looked at her as an infant, outraged, as though, somehow, she’d betrayed him by first bringing him into the world, and then trying to trick him into falling asleep. His eyes had a deep blue-grey, feverish lustre, exactly like Peter’s, and when he cried they turned flinty with anger. He seemed permanently unhappy. She felt like the worst mother in the world.

Peter came down from the city on weekends, and they would go for long drives. For a while this was the only thing that kept her sane. The baby, lulled by the engine, would pass out in his car seat, and they would cruise around the countryside, just talking. Or rather, Peter would talk. Heloise was frankly too exhausted to say much. But she would listen to his stories about university life, or his plans for his next philosophical lecture, and feel some small satisfaction that, even in her tired state, she could still keep up with his arguments. He was particularly illuminating on the subject of women. He went on and on about what a critical role they played in the development of early Christian life, and how they had taken a backseat in church hierarchy, which he felt was unfair. Peter considered himself a feminist, and taught her to apply that lens to history. Those were heady days. The term “mansplaining” had not yet been coined, so a man could say whatever he pleased. Speeding along in the afternoon sun with the radio playing the latest hit, Peter would be quoting St. Augustine at her without a shred of self-consciousness.

“If anyone doubts that women of holy life travelled with the apostles wherever they preached the Gospels, let him but read the Gospel itself and learn that in this they had the example of the Lord.”

Sometimes, the way he talked, she thought Peter should have been a priest. But when she told him this once, he’d laughed and said he preferred a healthy distance from organized religion, and that his interests were purely academic.

“Besides, if God is anywhere, he’s right here.” Peter had reached over the gearshift and put his hand on her upper thigh, giving her leg a good squeeze.

“Or she.”

“Or she.” That was how it was between them then. All ease and agreement. Give and take. And perhaps that is how it would have remained, if the baby hadn’t gotten sick.

It wasn’t just purple crying or colic, as the doctor had first assumed. Astrolabe, it turned out, was crying because he was in actual distress. He couldn’t seem to gain weight. At three months, he wasn’t showing the right signs of growth, and had poor muscle tone. The new phrase hurled at her was “failure to thrive” which felt like an accusation of the worst order.

“There’s something wrong with the boy,” her father-in-law said one day. At first, she thought he meant in general, for he was known to be blunt in his criticism. But when she looked closely at Astrolabe, she noticed a sickly bluish pallor to his lips and fingernails, like he had been sucking on a blue popsicle. Eerily quiet for once, he seemed not to be taking-in quite enough oxygen. Alarmed, Heloise bundled him up and rushed him to the doctor. Her mother-in-law drove, and Heloise held her baby while he took small, shallow breaths. Taking one look at Astrolabe’s blueish lips, the doctor had rushed him to hospital, where he was poked and prodded, attached to tubes, and given oxygen while he underwent numerous tests. The problem turned out to be his heart. “Congenital anomaly” was what the doctors said. A type of heart defect that affects one percent of all babies born. Her son’s tiny heart would require multiple surgeries.

The next few weeks were a blur. Looking back, Heloise could barely conjure them up. One thing she remembered was that Peter took a special leave from the university in order to be with them, only he wasn’t. He was strangely absent. He spent most of his nights in the local pub, drinking with his old elementary school friends, and during the day he avoided the hospital, claiming to have academic work that he couldn’t ignore. So, while Peter feverishly researched early monastic life and the evolution of celibacy practices in the Catholic priesthood, Heloise went to the hospital day after day, accompanied by her mother-in-law, where she was engulfed by terms like “hypoplastic left heart syndrome,” or “staged palliation.”

Heloise was baffled by Peter’s behaviour, but did not have time to dwell on it, as she was being bombarded by all kinds of questions. About the home environment she’d created for the baby, about the extent of her medical insurance, about what she would want done if he stopped breathing on the operating table. Everything was happening so quickly. Then, one day, they told her Astrolabe needed to undergo a very serious procedure. The doctors warned her the “actuarial survival rate” was less than 60%. She remembered sitting in the waiting room during this operation with Peter and both her in-laws, for even her father-in-law had eventually shown up when it seemed the situation was truly dire. She’d prayed then, to Mary, Jesus, and all the Saints to keep her son alive. To let his little heart pump blood smoothly so that he could live. Just live. For the first time in many months, she did not think about Peter.

Astrolabe did live through that surgery, but his grip on life was tenuous. Standing over his tiny body covered in bandages and wracked with tubes, they were told he would need several more operations. That it might take years for the full extent of his heart defect to make itself known. That he should not exert himself too much, ever. That he would not grow up to play sports. Worst of all, that he might not live to adulthood. Heloise, overwhelmed, looked at her Mother-in-law. The woman had an eerily serene look on her face.

“He’s going to make it. I’ll make sure he does.”

“How do you know that?” asked Heloise, her faith wavering.

“I just know.”

Peter excused himself then and left the doctor’s office, saying he’d be right back, he just needed some fresh air. It was the last time she ever saw him.

Still in hospital, Peter looked down at the stump where his thumb had been. The white cloth bandage was marred by a spreading spot of dark red blood that took the shape of a bird. A melody passed through his mind. A quick, nervous little tune, like a sparrow landing for food and then flying off. He pictured how he would form the chords on his guitar. Then he realized what state his hand was in and stopped, slumping back on his hospital bed. What was the point? The surgeon said he was lucky to only lose a thumb. He’d seen other men lose a whole arm, or a whole leg, he’d even once had to amputate a penis due to sepsis. The middle-aged doctor had raised his eyebrows comically. Peter supposed this was a surgeon’s idea of a pep talk. But really, how funny was this situation? To be badly injured at a Buddhist retreat. Pretty laughable actually, considering the whole reason he’d gone there in the first place was simply to stay out of trouble. When he thought of all the times he’d driven drunk, messed around with drugs, or climbed into a girl’s bedroom window, risking a broken neck just for the prospect of unprotected sex, he should have lost a limb a thousand times by now. Maybe more. It would serve him right if they had amputated his penis. Heloise though. Heloise had been worth it. Her absence in his life, the absence of his son, those were the real limbs he was missing. His hand, even though it hurt like crazy, was nothing compared to the loss he felt when he let his mind rest on Heloise and Astrolabe. That was a pain that seemed to come from somewhere deep in the earth and pulse right through him. Most days he just lived with it. The pain never left him, so he learned to negotiate around it, like an obstacle in the road. When he was feeling charitable towards himself, he could look at the mess he’d made of their relationship and chalk it up to his own inexperience. On those days, he could go for a walk, let himself feel the sun on his face, the breeze in his hair. Listen for the music. And he would be fine. But on days like today when he thought of her frightened, disappointed face as the doctor delivered the news about their son, a relentless funk of failure engulfed him, wrapping around him like a musty thrift store coat in the rain. Today it was all he could do to keep breathing.

The nurse came in. A different, older woman this time. She looked at him with pity, which almost made him cry. “It’s nearly dinnertime. Do you want me to wheel your table over?” Peter turned his back on her, putting his face towards the wall. “I’ll leave you alone then,” she said. Peter let her go, listening to the efficient click of her shoes disappearing. He had an overwhelming desire to write to Heloise again, to pour out his heart… share his regrets with her. But it wouldn’t be fair, would it? Plus, his thumb hurt too much to type.

From: P. Abelard < steadynow@hotmail.com” >

Dear Heloise – “Trickster of the highest order, eater of pistachios in bed.” Your emails cut right through my training and bring me face to face with myself. Reading your last one, I realized I had blocked out all memory of that day at the inn, and many others. Your words brought it all flooding back. I saw you again. Your hair. Your lips finding mine in the dark. Then, thankfully, I remembered what happened between us after that. I do remember hitting you. Even though you wanted me to, I’m not proud of it. And our breakup, the disastrous consequences that we both endured – you with your loneliness at grad school, me with the guilt of fathering a child but not sticking around to raise him… it was all too much. I had to let go. I had to move on. I am moving on. I’m living a different life now. Buddha said “Let go of the past, let go of the future, let go of the present, and cross over to the farther shore of existence.”

That is what I need to do.

Sincerely,

P.

“Do not pray for easy lives. Pray to be stronger men” — JFK.

Struggling to read Peter’s email on her tiny phone screen, Heloise cursed herself for leaving her glasses in her office. She was always forgetting them. It was becoming embarrassing. In class she often had to dig through her purse like a deranged old woman looking for her spare pair, or else teach the whole class locked in a deep squint. People said after you have children it softens your brain, and while she officially decried such unscientific codswallop as rhetoric of the patriarchy, she secretly she feared it might be true. On the bright side, it seemed she had succeeded in distracting Peter – at least temporarily – from his monastic mission. The knowledge of this gave her a small thrill. She still had it, at least where Peter Abelard was concerned. Squinting harder, she shivered and typed a response as fast as her two half-frozen fingers would allow. Then she hit “send,” and lit out across campus in search of a hot drink.

From: Heloise < lonepine@gmail.com >

Dear Peter – Who STILL cannot see the forest for the trees —

The Buddha said a lot of things. Like, “True love is born from understanding.” Or maybe it was the internet that said that. Hard to know these days, isn’t it? Either way, you are the only person who has ever really understood me. And while I agree that we both needed to step away from the intensity of our relationship, I can admit that miss you. Why did you leave? We never really talked about it. At the time I was too upset, and I guess you were too ashamed to offer any explanation so you just went away and left me to pick up the pieces. Back then, I know, it probably seemed like the only thing to do. But it’s a different time now. I’m different and so are you. We’re not in Paris, and we’re not in church. Anything can happen. Pigs can fly. I know this because even my stupid cousin Anselme (remember him?) is calling himself a “life coach” if you can believe it. He got Botox and a certificate from some 2-day course online. Now he’s always sending me links to articles that tell me what’s wrong with my life, and it makes me want to punch him in the mouth. I wish you’d come back here and defend my honour by debating actual philosophy with him. You’d wipe the floor with him. Hell, I could wipe the floor with him, but I’m just too tired. Tired of relatives, tired of students, tired of colleagues, tired of well-meaning stupid people. I miss our talks.

Heloise.

PS – You said “thankfully” you remembered our messy breakup. Why “thankfully?”

“We have become the men who we wanted to marry” — Gloria Steinem

When Peter left them, Heloise thought, she’d been forced to learn a lot of things, fast. That a tiny body could hold untold strength. That doctors could be cold, could have terrible breath and bad social skills, but that didn’t mean they were uncaring. That she did not need Peter as much as she thought she did, and that he presumably, did not need her at all. Most of all, she’d learned that people are not always what they seem, and that this could just as easily be a blessing as a curse. True, Peter had surprised her by pulling his vanishing act, but her in-laws surprised her too. First, by paying Astrolabe’s medical bills, which, despite the excellent French healthcare system, were considerable. Then by welcoming her and the baby back to their house, and having the courtesy not to mention Peter at the dinner table. Once Astrolabe was better, and once she was ready, they surprised her by helping her go to grad school. Her mother-in-law had insisted Astro stay with them while she went off to Vancouver to take her first job as a lecturer. Even her Father-in-law had spoken up.

“His friends are all here. He speaks French. He won’t know anyone there, and the food there isn’t what he likes.” Heloise had allowed herself to be convinced. Astrolabe was a very picky eater. She’d been told that all anyone ate in Vancouver was cheap sushi. Faculty housing was infamously cramped at the university, and there was a 2-year waiting list for the childcare centre. In France, Astro went to an excellent private primary school that served excellent French food and was serviced by an excellent medical staff. All this was paid for by her in-laws. He loved his grandparents. It felt cruel to take him away, yet she couldn’t stay any longer in her their home. It was simply time to move on. So, she’d boarded a plane, giving Astrolabe an iPad as a parting gift, promising to keep in touch.

That was six years ago. She’d put her head down and worked hard, getting tenure in record time. In fact, she was the youngest Chair their department had ever had, which occasionally caused resentment amongst her colleagues. They envied her, because they did not know her. They had no idea that there was sadness at the centre of her life, that she only saw her son on holidays. She and Astrolabe were not estranged, but they were not close, either. That was the sacrifice she’d made. That was her penance for everything she and Peter had put their relatives through. Astrolabe had recently been accepted to boarding school in Paris. Her old school, in fact. He went by Astro now. Sometimes they talked on WhatsApp, though Astro never had much to say, and always looked as if he would rather be doing something else. Like most boys his age, he was more about action than talk. None of her colleagues even knew she had a son. She listened to their endless diatribes about the rights of single mothers, but she never weighed-in. She didn’t want the scrutiny. Neither did Astro, it seemed. According to his school counsellor, who occasionally sent updates, he’d grown tired of answering questions about his absentee father and mother. He told his friends his parents were dead and he’d been raised by his grandparents. Heloise loved him desperately, but she felt she hardly knew him anymore, and worse, that she hardly had the right to. She sighed. Her phone beeped again. Another message from Peter. He hadn’t been this prolific since he was trying to get in her pants. She sheltered under a tree to read it.

From: P.Abelard < steadynow@hotmail.com >

Dear Heloise, my Sister in Resistance of All Things Stupid;I appreciate your concern for my well-being, truly. But I have learned that it is worth my while to look past yearning. To see through it. That said, I see no reason why we can’t talk, or at least communicate by email for now. At first, I was hesitant but now I remember how it feels to debate you. You’ve always been able to challenge me, and that has great spiritual value. I think even my shuso (head monk) would understand. Besides, I don’t really imagine your body the way I used to. I’m thankful for the time we’ve spent apart in that it’s allowed me to see the limitations of the path we were on. We were selfish. We were living only for each other, not our families, not our community, not even our higher selves. So, while I regret leaving you the way I did, and the pain it has caused, it was also instructive. Karmic, as the sages would say. I remember the shame I felt walking out on you that day in the hospital. I remember it every day, and it stops me in my tracks before I go too far down the path of imagining you naked. I notice myself noticing the memory of your soft skin, that little mole below your left breast, and I immediately notice the next thought, which invariably is shame, and failure. It’s a most effective tool for maintaining celibacy, believe me. The memory of our breakup pulls me back, makes me focus on the here and now. Our past is over, Heloise. It’s just not the path I am seeking to follow now, so I find it difficult to dwell on your beauty for too long. I am learning to conquer yearning and live in the moment. I suggest you do the same.

Yours,

P.

“Do not pray for easy lives. Pray to be stronger men” –– JFK

*

From: Heloise < lonepine@gmail.com >

Dear Peter, “Gee it must be great to be you” –Honestly, what are they teaching you at that monastery? How to be a sanctimonious dickhead? “I suggest you do the same”? You don’t know the first thing about me, or my life. You admit you’ve just blocked me out. You don’t find that a bit simplistic? So, let’s just pretend that I never existed, and you never walked out on your son… is that your big plan? The past happened, and it continues to affect the present. I would have thought with your capacity for extrapolation and your grand Buddhistic leanings, the “interconnectedness of the universe” would be obvious to you. You say you find it difficult to “dwell” on my beauty. Doesn’t that tell you something? Like maybe there are some unresolved feelings there? Besides, I’m more than my beauty. You haven’t seen me in nearly a decade. I’ve got more wrinkles, but fewer holes in my arguments. In my opinion you need therapy, not meditation. It’s all very well for you to spend your time “conquering yearning” when you’ve clearly got no responsibilities to speak of besides chopping wood or whatever. It sure doesn’t sound like you’re holding down a regular job, or servicing a mortgage, or trying to figure out how you’re going to pay for your kid’s braces.

Yours Anyway,

Heloise.

PS – Yeah, he got your teeth, poor kid.

“We have become the men who we wanted to marry” — Gloria Steinem.

*

From: P. Abelard < steadynow@hotmail.com >

To Heloise, the “High Dudgeon-ess of Vancouver.” Sorry if I came off as sanctimonious. And true – I was not there to help you while you were in the throes of what Buddhists would call your “householder” phase. But it’s not fair to say I don’t know the first thing about you. I do know you. I know the spark you carry into every room. I know your generosity. I know your smile. I know you. But as Thich Nhat Han said, “Our life has to be our own message.” Ever since we crashed and burned, I’ve been working as hard as I know how to figure out my own life and my own message. In the Dhamamapada it says, “If you cannot master yourself, the harm you do turns against you grievously.” I do not want any more harm to happen to either of us.

Yours,

P.

“Do not pray for easy lives. Pray to be stronger men” — JFK.

*

From: Heloise < lonepine@gmail.com >

Dear “Deliberately Obtuse” Peter –

Obviously, I don’t want any harm to come to you either, and I can tell I’m making you uncomfortable with talk of real-world grievances such as your son’s braces, so I’ll stop. But surely even Thich Nhat Hanh would admit that we exist in dialogue with other people. True, it’s not good to let yourself get too out of control, but at the same time, to quote an old favourite of yours – that wacky Canadian modernist, Charles Taylor – “The genesis of the human mind is not monological, but dialogical.” After all, we are nothing without our significant others. What I really don’t understand is how you can lock yourself away in your castle of mindfulness, pretending to ignore the world when there is so much pain in it, not the least of it being your own. All your walls of reason, all your secluded retreats and “noticing yourself noticing,” will not protect you from pain originating within yourself. You can hide away and meditate all you want but you will never be free from that pain until you feel it, confront it, and do what you can to step up and face the consequences of your actions. His name is Astrolabe, but he goes by Astro these days.

Heloise.

“We have become the men who we wanted to marry” — Gloria Steinem

*

Heloise stood still. The snow had started again. Everything seemed unreal. Altered. The relief of finally getting the chance to tell Peter how she felt was palpable. She felt disoriented, yet relieved, and somehow out of step with time. The effect of the snowstorm, she supposed. The absence of people on campus, the dampened soundscape, and then this exhausting flurry of emails containing more truth than anything she had written in the last decade. She waited nervously for another beep on her phone, but none came.

Two days later, Peter Abelard sat on a hard chair in the corner of his hospital room, trying not to scratch the place where his thumb had been. Underneath the tidy bandage the wound was mostly healed now, but itched like a Baudellairean whore. He was ready to be discharged. More than ready. He felt if he didn’t get out of there he might do something he’d later regret. But the paperwork was hung up. Something about his insurance. He hadn’t been able to answer Heloise’s last email. The older nurse had figured out he was using the staff wifi without paying, and changed the password on the ward. He hadn’t seen the younger nurse, the one with the great calves, since the first day. Restless, he was trying to meditate. Sometimes that helped pass the time. He tucked his legs up underneath him on the chair, and closed his eyes. He thought about a story he once heard, supposedly true, though it might have been from a movie. The Dalai Lama of Tibet was taking an international flight that had run into bad weather. Everyone on the plane was totally panicked. Lights were flickering on and off. Babies were crying, passengers were shouting, and quite a few people were throwing up. The flight was interminable, and when the passengers finally arrived at their destination, they were crumpled and traumatized. But His Holiness, in a deep meditative state for the whole flight, had remained blissfully unaffected, and stepped off the plane looking as fresh as a daisy. Meditation did have that power sometimes. But Peter was no Dalai Lama. For instance, right now he was being continually distracted by the beeps and blips of the nearby hospital machines, and the approach of footsteps. He gave up meditating, having just barely gotten started. Maybe it was the young nurse, coming to tell him his paperwork had gone through. Instead, his mother poked her head around the door.

“Darling.” She said. “Your poor thumb.”

“Mom?” he said, astonished to see her. “What are you doing here?”

“Well dear,” she said crisply, “you’ve let your insurance lapse. But our name is still on your policy as an emergency contact. The hospital phoned us when you couldn’t pay your bill. They said you were hurt, so we came straight away, of course.”

Perfect. His parents hadn’t seen him in ages and now they’d have to pony up for his hospital bill. In the past, he would have probably tried to dismiss this thought as a mere terrestrial concern, not worth worrying about in the greater scheme of things. But today he blushed. Heloise’s last email, the one where she’d said he needed to “step up” kept surfacing in his mind. Just then, his father appeared in the doorway. Peter sat up to greet him, then lay back down again abruptly when he saw who was with him.

Astrolabe. The son whose face he’d only ever glimpsed by lurking in the corners of Facebook, unobserved, but observing. The son he’d deliberately avoided crossing paths with by visiting his parents only when he knew the boy would be away at boarding school. Finally, the son he’d walked out on as an infant, as he lay on an operating table, his tiny pale frame facing down death. It was unforgivable. It was monstrous. Peter could barely meet the boy’s eyes, but he felt compelled to look at them. When he did, he found them to be clear, grey-blue like his own, and curious. The child looked at him quietly, as if making up his mind about something.

“Astrolabe, this is your father,” said his own father, matter-of-factly. For once, Peter was grateful for the older man’s tendency to suppress and ignore all feeling. When there is enough emotion in a room to stifle a soprano, no words can possibly convey the significance of the moment. At times like these, it is better not to have the hubris to try. Peter carefully offered out his unbandaged hand. “It’s good to meet you, Astro.”

Having heard nothing further from Peter, Heloise now stood in the lineup at the campus coffee shop. Her walk had taken her there, following a laughing pack of first years as they flirted and threw snow at one another. At long last, she felt the giddiness of the snow day grace her presence. She was in line behind a pretty young woman wearing a Cowichan sweater. She must be a local, Heloise thought. Her sweater looked authentic and had moth holes in it. Definitely not one of those fake Cowichans you get at the department store. Someone’s grandmother had knitted it. The girl had an unselfconscious beauty about her. Cheeks rosy from the cold, long legs in jeans and boots, dark hair peeking out from under a red toque. She turned to the boy beside her, who stretched his arm around her in a loose but possessive move that conveyed to the world, “she is mine.” They kissed. Heloise remembered the thrill she felt whenever Abelard did that with her in public. A seemingly casual gesture, but in it contained one of the most profound mutual agreements two people can make. I own you, and I allow you to own me. We own each other, reason be damned. Heloise smiled. What else was there? She ordered coffee, black, and headed back to her office.

*

Jennifer Moss is currently a Master’s student in the Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University. In her other life, she’s a new media producer, runs a podcasting company, and teaches Creative Writing for New Media and Podcasting at the University of British Columbia. Her writing focuses on the migration of ideas and stories across geography and spaces. She is also an audio storyteller with a long history of writing and producing for radio, and she’s the Creative Director at Vancouver’s JAR Audio. She is most interested in cross-genre and cross-departmental collaboration, and in continually exploring how emerging technologies open new doorways for writers. Editor’s note: Jennifer Moss has previously written a short story, A Modest Silence, and a Pandemic Letters poem, Sit Down, Death, for The Ormsby Review. Audio links: To hear Jennifer Moss’s audiobook of “Friendiversary,” click here for Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

*

Endnotes:

[1] Peter Abelard, “Dull is the Star,” translated by Stanley Lombardo, in William Levitan, Abelard and Heloise, The Letters and Other Writings, Hackett Publishing, 2007.

*

References:

Fraser, Giles. “The Story of the Virgin Birth Runs Against the Grain of Christianity,” The Guardian, Dec. 24, 2015

Luke. 1:46-49 Mary’s Song, “My soul glorifies the Lord and my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour, for he has been mindful of the humble state of his servant.”

Levitan, William. Abelard and Heloise: The Letters and Other Writings, incl. Abelard, Peter’s “Dull is the Star,” and “17: The Man to the Woman,” Hackett Publishing, 2007

Tanhavagga, ‘Craving.’ Translated by Acharya Buddharakkhita, 1996, www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/kn/dhp/dhp.24.budd.html.

Hanh, Thich Nhat. The World We Have, A Buddhist Approach to Peace and Ecology, Parallax Press, 2004

Taylor, Charles. The Malaise of Modernity, Anansi Press, 1992

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1083 Friendiversary”