1056 Beijing in Canada

Claws of the Panda: Beijing’s Campaign of Influence and Intimidation in Canada

by Jonathan Manthorpe

Toronto: Cormorant Books, 2019

$24.95 / 9781770865396

Reviewed by Trevor Carolan

*

Book-length critiques of our national failures of nerve and vision seldom make easy reading. Drug use policies, Quebec-ROC relations, Indigenous reconciliation, housing and environmental issues — on and on: it’s painful for a concerned citizen to look at the arc of Canadian life and feel unmoved when an indictment is levelled at government inaction that affects us all. That said, few books in recent years have presented as depressing a report as Jonathan Manthorpe’s account of Beijing’s efforts on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party to advance its strategic interests at the expense of Canadian sovereignty. Thankfully, somebody had the jam to write this important, overdue edition.

Book-length critiques of our national failures of nerve and vision seldom make easy reading. Drug use policies, Quebec-ROC relations, Indigenous reconciliation, housing and environmental issues — on and on: it’s painful for a concerned citizen to look at the arc of Canadian life and feel unmoved when an indictment is levelled at government inaction that affects us all. That said, few books in recent years have presented as depressing a report as Jonathan Manthorpe’s account of Beijing’s efforts on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party to advance its strategic interests at the expense of Canadian sovereignty. Thankfully, somebody had the jam to write this important, overdue edition.

Manthorpe is a veteran foreign correspondent with a lengthy newspaper career. In Canada, if you take interest in international affairs you’ve seen his work. For a writer, however, whether the subject is China or environmental literacy, the nature of filing columns is their limited length and the unrelenting frequency of deadlines compelled by the job. It’s difficult to keep pace with the in-depth analysis offered in The Economist, or the sort of insight the late Ved Mehta could deliver in Foreign Affairs. By contrast, this 290-page cataloguing of the blunderings of our national leadership elites regarding China and its Communist Party dictatorship is a wounding exposé of Canada’s relationship with China during the past fifty years. It goes in deep.

Manthorpe makes clear that he is concerned with the influence and agenda of the Communist Party of China (CCP), the 90 million strong organization that calls all the shots in the Middle Kingdom. “The tectonic plates of international power are shifting…,” he writes, and “the space on the international stage being vacated by Washington is inexorably being filled by Beijing.”

Should such blunt truth concern Canada? Does a donkey bray? Manthorpe notes forcefully that China’s politically expansionist aims have us in smack in its head-beams: “The Chinese Communist Party rides roughshod over Canadian values and is interfering in Canadian internal affairs to a degree that sometimes amounts to a challenge to Canadian sovereignty.” This interference, remember, comes from a nation that’s first to squawk when criticized from abroad over its appalling suppression of human rights in Tibet, Hong Kong, and among the Uighur Muslim people of Xinjiang (also long known as Chinese Turkestan).

Asserting that the CCP currently acts as a “classic imperial dynasty” with a “heightened sense of patriotism and nationalism,” Manthorpe notes correctly that once China began opening up significantly to the outside word during the 1980s, Western governments naively trusted it would conform to international protocols regarding something like the “established liberal-democratic order.” But why would it? With more than 2,000 years of continuous, if shifting, existential and cultural dominance in East Asia, the historic Middle Kingdom’s suzerainty over adjacent states like Laos, Cambodia, North Korea, and increasingly in Myanmar/Burma is being reimposed, and China’s export of its surplus labour is being poured into these and many other nations and neighbouring regions like Russian Siberia, Thailand, several Central Asian republics, and countries throughout Africa. Indeed, the prodigious ‘One Belt and One Road” infrastructure initiative with its new superhighways and railroads is in process of directly connecting China with points as far south as Singapore, and as far west as the Atlantic coast of Iberia. Compounding this is Beijing’s “Maritime Silk Road” strategy linking China with the overseas natural resources and markets of Africa, South America and beyond — a development that ought to have any contemporary leaders studying their geopolitical horizons closely.

In a well-researched chapter, Manthorpe details at length how Canada’s political relationship with China took root in the 1880s via Christian missionary work. Oddly, one of the finest books on this subject isn’t mentioned — Beyond The Moon Gate, A China Odyssey 1938-1950, adapted from the diaries of Margaret Outerbridge by John Munro (Douglas & McIntyre, 1990) offers sparkling illustration of how, as Manthorpe contends, the job of “saving souls was personal and visceral” to Canada’s China missionary corps. Ironically, this nanny complex produced an influential crop of “Mishkids” –- the children of missionary families who learned Mandarin language skills there. Often raised in social reform-minded Christian traditions, they grew to become many of Canada’s top academic and diplomatic experts on China. Tellingly, Manthorpe observes this was not necessarily favourable in Ottawa’s cultivating an unblinkered view of Chinese Communist policies. Canadian relations with Beijing were empathetic during Pierre Trudeau’s era, notably regarding its emergence on the world stage through entry to the U.N. — in which Ottawa played a critical role. However, but they did not evolve sufficiently in terms of threat analysis to avoid the eventual typhoon of exploitative assaults on Canadian economic, cultural, and even its political integrity launched from China. Manthorpe’s book points to the theft of militarily-sensitive digital technologies, money laundering scams on a colossal scale, subsequent corruption of major Canadian real estate markets, and the systematic harassment of Chinese-Canadians and members of the country’s pro-independence/pro-democracy Uighur, Tibetan, Taiwanese, and Falun Gong communities, among other egregious matters.

Nevertheless, the author notes his book is not “a doomsday saga.” Nor is Canada the only chump state in allowing such Chinese Communist Party initiatives to have their way on our home turf. Similar things can and have taken place in other Pacific Basin nations, notably Australia, New Zealand, and in the U.S. and Europe. He avers that “the Australian experience of infiltration by the CCP is almost exactly the same as that of Canada. The difference is that Australian politicians, academics, media, and the public have been a good deal louder and more pointed in their objections to the CCP’s campaigns.”

Manthorpe reminds us that it’s good to know who you’re in the ring with. What we should have learned from decades of the Cold War is that, “the CCP maintains that the interests of the party outweigh all other considerations.” He says flatly that the CCP treats Canada as a battleground in which it “seeks to terrorize, humiliate, and neuter its opponents. It is a war being conducted in plain sight, but largely unremarked, as the CCP’s diplomats, spies, security officers, and local agents of influence go about the daily business of trying to nullify the efforts of those it believes are set on over-turning China’s one-party state.” The result, he contends, has been “a chilling effect on human rights activism in Canada and interfer[ence] with many Canadian citizens and residents of Canada’s rights and freedom of conscience, expression and association.”

Proof of the systematic surveillance and harassment of Canadian citizens comes, the book reports, from the defection of the spouse of a Chinese embassy official in Ottawa in 2007. This individual had become a Falun Gong member — the Buddho-Taoist movement that challenges the hegemony of the CCP and once with 15,000 members peacefully surrounded the Beijing super-compound where most of CCP top brass reside, terrifying the new “red aristocracy.” The defector brought an account of “activity in the embassy” that included activities identified by Amnesty International as “harassment and intimidation.” Also noted is the Falun Gong member who blew the whistle on China’s cover-up of the SARS epidemic in 2003, an event with eerie similarities to the way that the COVID-19 catastrophe was first handled by Chinese authorities.

Thoughtful readers will expect an answer addressing how China’s communist dictatorship has been so successful at infiltrating and influencing key aspects of Canadian life. Manthorpe explains admirably, “They are most comfortable operating in Western democracies when they find people who can be charmed or suborned. And it is never hard to find people whom the old Soviet communists used to call “useful idiots.” Ah, we’re getting warmer: so who might these toadies be? His insightful list describes a steady stream including “political party and government leaders, rank and file politicians, naive and hubristic academics, greedy and gullible business people, and even some parochial and inexperienced journalists.” Hey, a free trip to China is always agreeable! Those with some experience in Canada’s Asia-Pacific affairs domain will have little difficulty attaching names to some of the blanks. For a few of the most embarrassing actors, consult the book.

Much of the problem Canada has experienced with CCP-directed activities and infiltration was outlined some years ago in a controversial intelligence report code-named “Operation Sidewinder.” The report analyzed how the CCP actively engages in promoting “a narrative favourable to its views” within the large Chinese diaspora, including Chinese students and business people living in other countries. Compiled by Michel Juneau-Katsuya, the head of CSIS’ Asia-Pacific desk — that’s the chap in charge of our senior national intelligence agency for security issues regarding China — the report had plenty more revelations, focusing Manthorpe says, “on the potential dangers posed for Canada by the troika of CCP intelligence agencies, Hongkonger and Chinese entrepreneurs with strong links to the CCP, and Triad gangs that the CCP had publicly called ‘patriotic organizations.’” That ought to scare the pants off any Canadian citizen.

Sidewinder detailed how the complex troika was infiltrating and influencing significant areas of “Canadian corporate and public life,” as well as “control of strategically significant Canadian technology and resources.” Fair enough, that’s a pattern of neo-colonial investment familiar to any backwater developing country. But Sidewinder — leaked to journalists — cranked up the anxiety in maintaining that “the rapid growth of all this becomes an excellent vehicle to gain access to local politicians and their influence and power.” Short version, “the CCP is a challenge to national security.”

What was the result of this high-ranking research direct from within the heart of our national intelligence agency? According to Manthorpe, high-placed authorities in the intelligence and RCMP services, in addition to federal bureaucrats went out of their way to challenge, block, or subvert the report’s information. Outgunned by the opposition, underfunded, overwhelmed by the scale of the challenge, it was easier to remain silent, then tarnish the report’s value with a tsunami of disavowals, rejections, and disputed evidence. Manthorpe explains that the report was in fact vulnerable. There were holes in its analysis. What he also says makes it sound like Inspector Clouseau was at the helm: evidently, the original was written in French, with a lousy translation riddled with grammatical errors. Who the devil is in charge of hiring in Ottawa? The Mounties and CSIS were reportedly at odds regarding the conclusions and recommendations; and “to cap it all, there were reports that much of the material gathered in preparation of the sidewinder report has been destroyed.” Gee, Mr. Watergate, how convenient is that? Only it wasn’t a crappy B-movie: this was from the A-team in charge of our national security. When a high-brow Security Intelligence Review Committee including several nationally-known politicians looked at the report, it concluded the first draft was “deeply flawed in almost all respects. [ It] did not meet the most elementary standards of professional and analytical rigour.”

Anyone who’s seen Guys and Dolls knows that race-track gamblers follow a nag’s form. Even an undergrad scholar might be prompted to ask, “If the guy who wrote the report was that awful, what was he doing heading our nation’s most sensitive intelligence desk?” The next logical question would be, “And if he’s really that bad, who is responsible for hiring him in the first place?” In politics these kinds of lousy moments are called “the sniff test.”

There is ample discussion of Chinese efforts to manipulate media coverage of China and its policies, notably by acquiring friendly ownership interest in Chinese language publications and media outlets. Manthorpe notes the CCP’s reliance on “the United Front” — a cohort of direct and indirectly-related organizations that promote China’s interests by whatever means gets the job done. Surveillance and coercion of international students, promotion of soft cultural exchange programs, a bit of technical espionage here, cultivation and grooming of Canadian political figures there. Approx. 70,000 Chinese students a year are drawn to Canada, making them “a major source of infiltration into Canada by the CCP’s intelligence agencies and the United Front.” What began as a modest exchange of students has since mushroomed to the point where “many universities in Canada and elsewhere have made themselves prisoners of the large amounts of money that they are now receiving from international students, especially those from China.” With that comes a reluctance “to turn off the tap.” Subsequently, bad habits have arrived such as, “A whole industry [that] has grown up in China providing fraudulent paper qualifications for students wanting places in Canadian and other foreign universities and colleges.”

There’s also the matter of planted Beijing sympathizers within Canadian classrooms. The recent growing reactions to Beijing-sponsored “Confucius Institute” programs are a case in point. Designed to inculcate China-sympathetic political views among Canadian and other host nation students, their job as Manthorpe makes clear is both to confine freedom of speech, and to encourage the political censorship of unflattering views of China — core thrusts of United Front activity.

In business meanwhile, prominent eastern Canadians have set the pace. Power Corp. under its founding chairman Paul Desmarais established extensive business dealings with China and, Manthorpe contends, emerged as “the premier gatekeeper of this country’s formal relations with China.” Desmarais’ intimate association with the federal Liberal party was felt through the elder Trudeau, Chretien and Paul Martin administrations and it had effect. Canada’s old moral, missionary impulse in official China policies would be subsumed by a business perspective. A diminished Canadian emphasis on human rights in our China dealings would be compensated for by greater wheat sales and job creation. Ottawa’s bureaucratic eunuchs — known as “fart-catchers” as Allan Fotheringham once informed me — sustained this view, even as our embassy diplomats contradicted them from Beijing, warning that “Canada appears mesmerized by China … but dialogue will not produce Chinese recognition as a world mover and shaker.” The boots-on-the-ground recommendations of our experienced diplomats were left ignored.

It gets worse. The much-vaunted Immigrant Investor Program that was promised to be a boon for the Canadian economy now looks little more now than a cash-for-passport scam on a par with what went down in other progressive nations like Tonga. Manthorpe relates that it was perforated with loopholes, fraud, and the ridiculous possibility that the individuals concerned could actually borrow the promised investor sums from Canadian banks once they’d landed. What kind of morons dreamed this up? A forensic report in 1998 found the program “riddled with fraud” and that “claims made by Immigration Canada about the program’s success were a gross exaggeration.” That sucking sound from the quicksand was Canadian immigration consultants being drawn into the use of fraud and deceptive documents. It’s reminiscent of B.C.’s casinos/money laundering scandal in which the dazzling lure of easy money grew to corrupt the fuller conspectus of Vancouver’s real estate market. When the inept program was finally junked in 2014, “of the 59,000 applications pending, 45,000 were from mainland China.”

Don’t ask about organized crime being quick to seize on the exodus of Chinese immigrants into Canada. Don’t ask about complaints to Canada’s Hong Kong Mission and the RCMP of expedited visas for cash, or the unresolved disappearance of 2,000 blank visa applications, or the use of counterfeit visa stamps, or even the suspicions that computer systems used to track the biographies of known criminals were hacked. Don’t bother because all these issues have been voiced and the results have been more numbing dead ends from the Ottawa fart-catchers. Manthorpe claims that aggressive RCMP investigators were either ignored or pulled off cases. Does that pass the sniff test for you?

What is Canada to do? Manthorpe concludes with a rebuke, stating “the Canadian public … shows a more grounded view of China under the CCP and the dangers in represents than do the actions of the establishment classes that have benefitted from their relationship with the Beijing regime for nearly fifty years.” He says bluntly that Canada must abandon its past-due date missionary spirit in dealing with the CCP. This includes a call to politicians and academics to show some backbone in speaking out in defence of Canada’s sensitive industries and intellectual property, and against China’s human rights abuses at home and in Hong Kong. Geopolitically and morally, he asserts we should be speaking out clearly in support of Taiwan, and we should expand our trade, military, and cultural alliances within the East, South and Southeast Asian regions, “notably Indonesia” that has shown some spine in territorial disputes. Internationally, we should be comprehensively strengthening our cultural, political, economic and security links with our trusted NATO allies, and adopting a “more self-assured attitude toward Beijing than is now the case.”

Canada’s speaking out against the savage repression of the Uighur people is a start — a Parliamentary initiative not from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who was notably absent for the Uighur genocide vote, but from Erin O’Toole’s Conservative Party. Recognizing who’s behind those full-page advertisements by pro-China groups and China apologists in Canada’s major Chinese-language newspapers expressing support of China’s Winter Olympics in 2022 is another step. Perhaps you might keep former diplomat Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, the Canadians being held in Chinese prisons, in mind while you decide your own opinion. Meanwhile, Huawei’s CFO-under-house-arrest-in-Vancouver Meng Wanzhou will have to continue managing with life in a mansion, limousines, and specially arranged family visits.

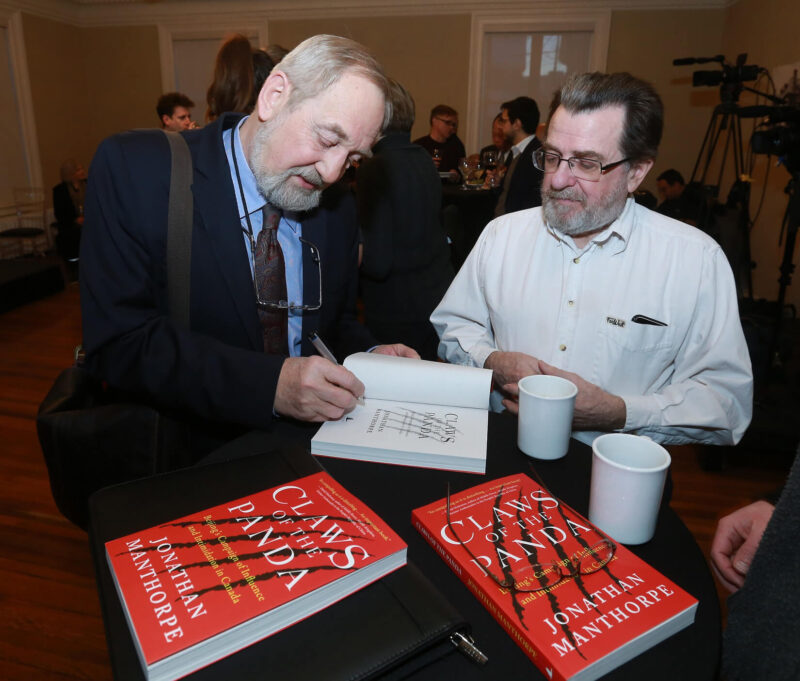

After reading this book you’ll be a lot better informed about whether the claws of the panda are sinking deeper and deeper into our society. As Canadians we deserve better. So do the decent, everyday people of China with their marvellous history, along with the equally decent, typically younger government officials who know that there are things afoot which are not right. There is plenty more courageous work ahead needed by both our tribes. Meantime, a bow in admiration to Jonathan Manthorpe for the diligent research, perseverance, and more than a little bravery that has gone into this exemplary study.

*

Trevor Carolan has previously reviewed books by Michael Schauch, John Lent, Francis Mansbridge, and Daniel Francis for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1056 Beijing in Canada”