1031 Where are my people?

Burning Province

by Michael Prior

Toronto: Penguin Random House (McClelland and Stewart), 2020

$21.00 / 9780771072345

Reviewed by P.W. Bridgman

*

Editor’s note: The West Coast Book Prize Society announced on April 8, 2021, that Burning Province, by Michael Prior, has been shortlisted for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize in the 2021 BC and Yukon Book Prizes. Winners will be announced on Saturday, September 18th, 2021 — Richard Mackie

*

Michael Prior’s star is swiftly rising, and for good reason.

Michael Prior’s star is swiftly rising, and for good reason.

This young poet, born and raised in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, is now an assistant professor of English and a Mellon ACM Fellow at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. In 2020, Macalester was ranked by US News and World Report as the 27th best overall in a rating of liberal arts colleges across the USA. (There are 223 of them.) Prior’s appointment to the professorship and fellowship he now holds is a signal achievement on any analysis.

After completing his first degree in English Literature at UBC, Prior went on to earn two master’s degrees — an M.A. in English Literature from the University of Toronto and an M.F.A. in Poetry from Cornell. While at Cornell he was mentored by poets of the calibre of Ishion Hutchinson.

Auspicious beginnings to be sure.

Those beginnings have proven to be fertile ones. Prior has built upon them, rapidly and surely. Burning Province is recent and compelling evidence of that.

Along the way as he was pursuing his postgraduate studies, Prior has been writing prolifically. Burning Province is, in fact, his second book of poems. The first, entitled Model Disciple, was published by Véhicule Press in 2016 and it was chosen by the CBC as one of the best books of that year. Of the debut collection, Jay Ruzesky was moved to say, in a review published in the Malahat Review:

…In many ways — the range of interests, quality of language, the attention to rhythm — Prior’s work is a kind of blend of P. K. Page and Karen Solie, but I make those comparisons only to say that his work is already polished and self-assured.

In fact, Prior’s poetry has, from early days, attracted the attention and admiration of some of the most exacting editors, not only in Canada but across the world. His work has been published in top tier journals such as Vallum and Grain (Canada), PN Review and Ambit (UK) and Poetry and The New Republic (USA), to name a few. He has won poetry prizes in competitions sponsored by The Walrus, Vallum and Matrix Magazine. His poems are represented in the 2018 anthology, The Next Wave: An Anthology of 21st Century Canadian Poetry.

On it goes. And he is barely 30.

When a writer of such promise — one who has already achieved so much — presents us with a new title, it behoves us to take notice. And people have. Burning Province has drawn new accolades for Prior, acknowledging that his writing is sure-footed and consistent but also growing in maturity, referential depth and technical sophistication.

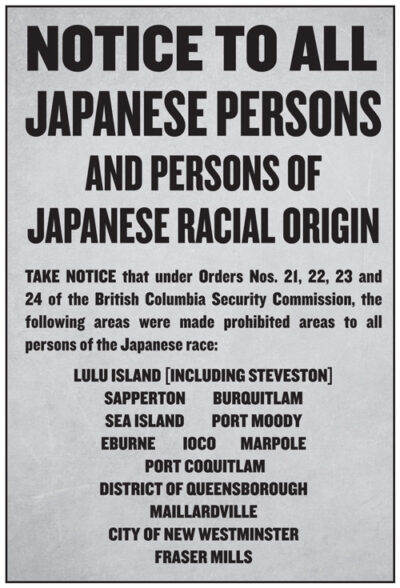

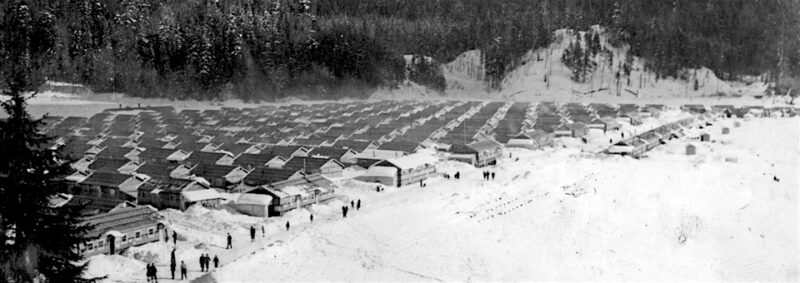

As a bi-racial poet, Prior looks in particular to the Japanese branch of his ancestry for much of his inspiration. His maternal grandparents figured prominently in his upbringing. The seldom-discussed suffering and dispossession they experienced during the internment of Japanese Canadians during WWII is an ugly historical fact that Prior struggles to understand, process and come to grips with in his poems. Juxtaposed against what he knows of his grandparents’ character, their kindness, their quiet dignity and their slowness to anger and complain, that ugly historical fact seems entirely incomprehensible. Prior’s engagement as a poet with the troubled history of the Japanese side of his family began with Model Disciple and it has enlarged and deepened in Burning Province.

Prior’s is, necessarily, a poetry of identity, of exploration; it embodies a quest for understanding of grievous historical wrongs and the ways they continue to resonate, like a rung bell, up to the present. His poem “The Light from Canada,” records these troubled words:

…I worry about you, said my grandfather

for whom my feelings

remained irrevocable. I had thought myself

worried for him, too. It was late:

we ate blackberries from an earthenware bowl,

drank instant coffee, and stood

by a bonfire in the rain

because it was New Year’s,

and he had no home

he could return to.

As the details of the internment initiative that swept his grandparents and his mother from their homes (nay, from their very lives) began to come into focus for Prior as he matured — an initiative that consumed their history like a raging but controlled and purposefully directed forest fire — he struggles mightily to understand them. He struggles too to comprehend the trappings of biracial identity as they begin to emerge in his own life (indeed even within his own extended family). In a particularly poignant passage in the poem “White Noise Machine,” Prior recounts a time when he and his father, together in the family car, cross what one infers is the B.C./Washington border. They find themselves under perplexed scrutiny by the border patrol. Father and son do not look entirely alike and at moments like these the boy senses the distance between them acutely. The experience leads the boy to reflect on the perspective held by his grandmother on the other side of his family and to wonder:

…How old was I

when his mother wished my brown eyes would fade

to blue?…

…Waved through, I nod,

eyes down.

Small intimations of such intolerance recur, reinforcing and underscoring what divides us instead of what unites us: each such intimation a grain of salt added, one by one, to a wound undeserved that throbs quietly in a still barely comprehending young soul. The signs of what we now call “othering” appear at the most unexpected times and places; as Prior shows us, they slip effortlessly and without thought, even from the mouths of well-meaning old family friends.

…New worlds

forever measured by the Old. For every measure

an equal and opposite erasure. How, over the fire,

the family friend said, Jap, not Japanese.

O the banality of evil.

The warm spirit of Prior’s now deceased grandmother haunts this book. In Dylan Thomas’s words, hers is the “force that through the green fuse drives the flower” of Burning Province. She is the kind of grandmother who will yield good-naturedly when her grandson pleads with her to rewind and replay, again and again, his favourite part of The Return of the Jedi recorded on VHS tape. These and other endearing (and sometimes quirky) facets of her, and of her relationship with Prior during his childhood, are revealed in various places throughout Burning Province. She had, for example, a great admiration for the actor Sir Roger Moore (whether it was as Simon Templar in The Saint or as James Bond in Live and Let Die we are not told). She was also particularly fond of Hallmark Christmas ornaments. She fed sugar water to honeybees with a spoon (and coins with which she could barely afford to part to Prior when he was still a small boy). Lovely.

“Quiet dignity” is such an overused phrase; it recurs in obituaries every day and so its currency has been devalued. Yet the phrase does perfectly capture Prior’s grandmother’s indomitable and uncomplaining ways (“uncomplaining” being different from “accepting”). She shares a few details about the depredations she experienced during internment with Prior as she begins her final decline. An adult now, he listens while keeping a vigil in her upper-floor hospital room at VGH as she lays dying. The sky outside her window is a startling red and orange. Smoke drifting west from forest fires razing parts of the Interior transmutes the fading sunlight into a fiery tribute to the last hours of a woman who, along with her ethnic community, had undergone a similarly destructive razing of sorts a generation earlier. The exquisite parallel is revealed with masterful subtlety.

One sees so much to admire in Prior’s grandmother. She emerges full-blooded in the deftly rendered poems that Prior has crafted as a kind of homage to her and to the central role that she played in shaping his life. Writing that seeks to celebrate the gifts that pass between the young and the adults who have shaped them approaches the sacramental. The same might be said about writing that seeks to mark the moment when such a person at last slips away (and all that that means and connotes for the one left behind). Prior is a poet possessed of the lyrical gifts that are needed at such times. He has done justice to his grandmother’s life and legacy and to say so is to say a great deal.

Burning Province is not an easy book. In places it is incredibly raw. Travelling in Prior’s company to Tashme for example — the internment camp to which his grandparents were relocated by force (now an RV park, if you can believe it) — makes for a rough emotional ride. It is a ride, however, that one should not decline to take.

But beyond the discomfiting subject matter that is addressed in some of the poems, readers will also sometimes be challenged by Prior’s use of language. It is idiosyncratic, adventurous and sometimes even obscure. But persevere! Burning Province must be approached on its own ground. One doesn’t read Joyce the way one reads Ian McEwan any more than one reads bill bissett the way one reads Wordsworth (or Ange Mlinko the way one reads Elizabeth Bishop). Prior’s poems are not all packages into which meaning has been skilfully and cleverly tucked. Sometimes they create odd and intriguing visual imagery. Savour it. Quite often the writing is deliberately musical. The percussive plosives, the extended vowels and the susurrating sibilants and fricatives can give pleasure to the ear that is rooted in the poetry’s rhythmic and melodic features. Savour that, too. Falling back on what high school English teachers may have told us about the need to unlock the secret meaning that is said to be lurking inside every poem will sometimes get in the way when reading Prior. Like many poets he works on multiple levels and to truly appreciate him, readers must do so too.

In the opening lines of his poem “Richmond,” Prior asks, perhaps not entirely rhetorically, the question: “Where are my people?” It is a question that sounds in a distinctly minor key and Prior will likely continue to ask it throughout his lifetime. This is the legacy that the unforgivable and unforgiven mistreatment of his Japanese forebears has conferred upon him. But, by degrees, answers have begun to emerge. We see that in Burning Province. Bearing witness to the mistreatment of his forebears and forging the legacy of that mistreatment into something new and beautiful which acknowledges and confronts it has already drawn many grateful and admiring readers to Prior.

Those readers come away, in turn, enlightened by the truths he tells and struck by the poetic skill with which he tells them. Burning Province — a collection that Lisa Russ Spaar praised in the pages of the Los Angeles Review of Books as being “ferociously beautiful” — will draw him many more such readers. One might then say to Prior that, though his quest continues, he need look no further than to that growing body of admiring readers to find some, at least, of “his people.”

*

P.W. Bridgman writes from Vancouver. In 2018 he studied poetry with, among others, Ciaran Carson, Doireann Ní Ghríofa, Leontia Flynn, Gerald Dawe, Edna Longley and Stephen Sexton at the intensive writing summer school program offered by the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry at Queen’s University, Belfast—an experience that he says was a transformative one in his writing life. Bridgman’s second selection of poems, entitled Idiolect, will be published by Ekstasis Editions in June 2021. His second book of short fiction, The Four-Faced Liar (also published by Ekstasis), was released at the end of January 2021. Bridgman’s poetry and fiction have appeared in The Maynard, Grain, The Antigonish Review, The Moth Magazine, The High Window, The Glasgow Review of Books, The Honest Ulsterman, The Galway Review, Ars Medica, Poetry Salzburg Review and other periodicals and anthologies. Learn more at his website. Editor’s note: P.W. Bridgman has also reviewed books by Leslie Timmins, Marilyn Bowering, and John Swanson for The Ormsby Review, and his book of poems, A Lamb, was reviewed here by David Stouck.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster