1022 A poet addicted to language

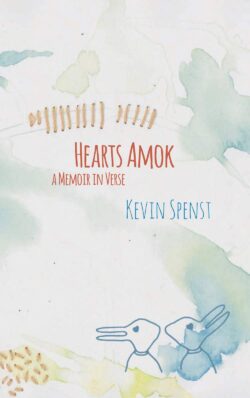

Hearts Amok: A Memoir in Verse

by Kevin Spenst

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2020

$18.00 / 9781772141498

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

One of the most basic requirements of any poet is that he or she is addicted to language. Other specialized knowledge and skills can come later, but a burning curiosity about words, their origins, and their nuances together with an urgent desire to sound them out, and where necessary to change them, is essential.

One of the most basic requirements of any poet is that he or she is addicted to language. Other specialized knowledge and skills can come later, but a burning curiosity about words, their origins, and their nuances together with an urgent desire to sound them out, and where necessary to change them, is essential.

Likewise, among poetry’s great services is its ability to infiltrate new words or new nuances for existing words into the common language: Gerard Manley Hopkins and Dylan Thomas — and at a less significant level, E.E. Cummings — are among modern English poetry’s most prominent inventors and renovators. But whereas for them forging new terms was a means to an end, for Kevin Spenst, as also for that most Protean of 20th century English poets, W.H. Auden, play is an essential element in even the most serious meaning.

Such linguistic play, which in the case of Hearts Amok owes a lot to James Joyce, is serious but never solemn. Part of poetry’s hold over us is its ability to concentrate two or three suggestions or overtones in a single word. Thus, in his account of earlier relationships he starts one poem by imitating Cupid (italics mine):

In those textbook days he aimed for the eye,

a quiver to a quaking heart

Elsewhere, “on higher ground,/ my bed has sprung a squeak,” while, referencing the Troubles in Ulster, he writes:

You

grow up down that rain-slicked road

into Belfast with your Da delivering

tulips within bombshot of new

and antiquated atrocities

While we all have our own personal vocabularies, Spenst has a far wider range than most of us. So, leaving aside the many words, such as bindle or yegg or prushun that he acknowledges culling from A Dictionary of Old Hobo Slang, he deploys many others that seem to be inventions. Some of these work — in context, the meanings of “escapology” or “suaviate” may seem self-evident — but others, such as “vexillology” or “proprioception” that I could find neither in the Shorter Oxford nor in slang dictionaries, and that are not glossed in the unnecessarily long notes at the end, remained opaque and counterproductive. However, the poet’s omnivorousness is not confined to vocabulary. His apparent familiarity with a wide range of literature is equally impressive. Hearts Amok overflows with literary allusions.

Sometimes it is a matter of deliberate misquotation, as when Spenst starts, “How do I lust after thee?” with “Let me count the waves of longing.” Sometimes he quotes Chaucer or Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, or Gertrude Stein as epigraphs. Sometimes he modifies a line from Cummings (“puddle-wonderfully”) or concludes a self-ironic poem about reaching middle age with a nod to Dante’s Inferno:

My rocking chair back creaks.

Midway through the journey of our lives we came to.

He even provides the reader with an updated version of a Petrarchan love sonnet:

I neither know

your neck nor body, so here’s where I wing it

your breasts, belly and back are a murmuration

of starlings, your legs an exultation of

meadowlarks. Let me learn your eyes:

an unsettling of doves that quickends pulse

and neurons.

In short, although it is not essential to have read widely in English literature to enjoy Spenst’s verse, it certainly adds to one’s pleasure to recognize an allusion or savour a pastiche. Nor is he lacking when it comes to knockabout humour, mostly by way of unexpected analogies: I laughed out loud at “When I think of your lips they redden / like stove elements.”

There seems virtually nothing linguistic or literary that Spenst cannot coax and twist to his narrative and emotional purposes. Occasionally a pun or play on words will seem strained, not worth the effort, but for the most part they work to enhance the roller-coaster sensation. For while it is easy to be distracted by the sheer haphazard energy of this work, the multi-layered effects are subordinated to a serious attempt to come to terms with the poet’s growth over time from adolescent lust and infatuation to the development of an enduring love.

Impressively, despite this welter of moods and incidents and feelings, the dominant approach to experience is through and with he play of ideas. Thus, approaching the end of a relationship,

(we) convince ourselves that another date’s a good

idea where and when it feels like we’ve been catapulted

in the direction of each other in slow motion.

I hate slow motion.

We miss. We feel like a medieval syllogism

on a loop. Thus, we tumble apart as strangers

Sometimes it’s simply a matter of an unexpected image:

she runs into me like she’s about to dive/ into a lake

And how’s this as an evocation of the moments before lovemaking?

We genuflect

in a ceremony of touching, go gung ho

into the amalgamating depths.

The same verbal intelligence is at work when the poet suffers what seems to be a mini-stroke:

My vision blags. My arm

baulks outside proprioception. Half my body land-

slides. From the ambulance, the city dragons like

the Book of Revelations.

It’s hard to envisage a more tactile rendering of this situation, and all without a hint of self pity or posturing. But then, this poet’s magpie eye is constantly on the look out for stray connotations, echoes, and suggestions.

If, at one level, this book is a gallimaufry of all the tricks of the poet’s trade, where no sleight of mind or heart is off limits, for the alert reader it is also a thorough emotional and intellectual workout. Take it or leave it, it is a package deal. At the very least it should get us back to the language, our language, and leave us asking for more.

*

Born in London, England, in 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught English, Creative Writing, and Comparative Literature at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. He has written twelve books of poetry, the most recent of which is A Tattered Coat Upon a Stick (Quattro Books, 2017). He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978, was its editor for the first ten years, and was for five years Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. He has reviewed widely, mostly poetry and South Asian literature in English, in the UK and Canada. With his wife, Oonagh Berry, Christopher moved to Vancouver in 2007 where he helped re-start and run the Dead Poets Reading Series. Editor’s note: among the books Christopher Levenson has reviewed for The Ormsby Review are those by Derk Wynand, Daniela Elza, Sarah de Leeuw, Susan Buis, Miranda Pearson, E.D. Blodgett, Nicholas Bradley, David Zieroth, and Kate Braid.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1022 A poet addicted to language”