1009 Reclaiming Indigenous history

Kwanlin Dün: Dǎ Kwǎndur Ghày Ghàkwadîndur – Our Story in Our Words

by Kwanlin Dün First Nation

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2020

$50.00 / 9781773270784

Reviewed by Daniel Sims

*

Editor’s note: The West Coast Book Prize Society announced on April 8, 2021, that Kwanlin Dün: Dǎ Kwǎndur Ghày Ghàkwadîndur – Our Story in Our Words, by Kwanlin Dün First Nation, has been shortlisted for the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize in the 2021 BC and Yukon Book Prizes. Winners will be announced on Saturday, September 18th, 2021 — Richard Mackie

*

2020 certainly was an interesting year in academia. For the most part campuses were vacant, with classes online, and overall productivity negatively down. One should not think, however, that research stopped altogether, and when it came to publications there may have been delays, but things still got published. One such publication is Kwanlin Dün: Dǎ Kwǎndur Ghày Ghàkwadîndur Our Story in Our Words. I was excited to be given the opportunity to review this book and it did not disappoint.

2020 certainly was an interesting year in academia. For the most part campuses were vacant, with classes online, and overall productivity negatively down. One should not think, however, that research stopped altogether, and when it came to publications there may have been delays, but things still got published. One such publication is Kwanlin Dün: Dǎ Kwǎndur Ghày Ghàkwadîndur Our Story in Our Words. I was excited to be given the opportunity to review this book and it did not disappoint.

Written by members of the Kwanlin Dün First Nation itself, the self-titled book is a general history of the nation from the earliest times to the present. It is part of a wider corpus of recent Indigenous histories — e.g. Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws, by Marianne and Ronald Ignace, and Where Happiness Dwells, by Robin and Jillian Ridington — written by community members and aimed at the community itself. As such, it is much more concerned with capturing the views of the community rather than entering into any sort of academic debate and/or employing a particular theory. This approach is increasingly common as researchers genuinely engage with Indigenous communities on the communities’ terms. And while I cannot speak to the rationale of the Kwanlin Dün nation to make this decision, I can say that in my experience as an Indigenous historian, who works with his home community, that many Elders are not interested in such things, especially if they think the writer is trying to legitimize the nation’s history through said debates and/or theories.

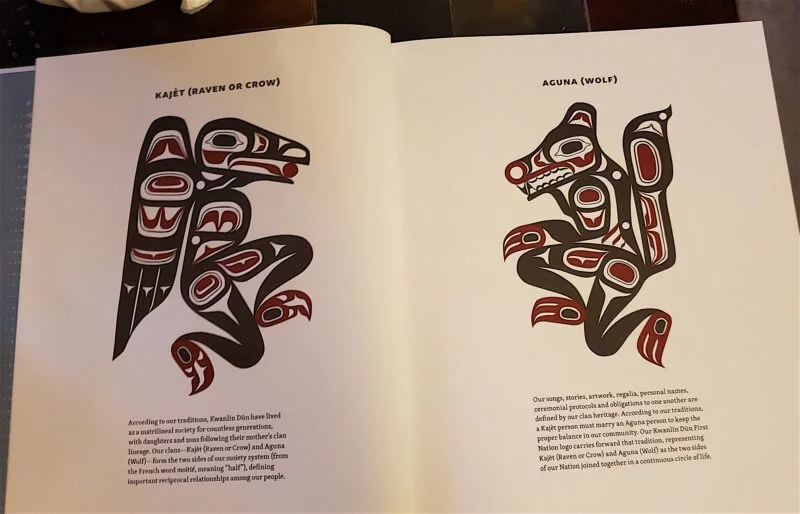

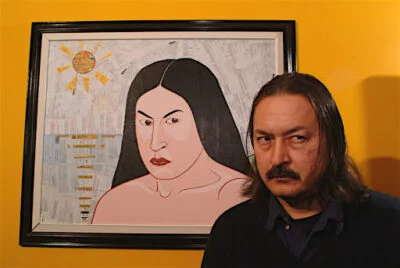

At its heart this is a book firmly founded on the Kwanlin Dün nation. The authors dedicate it to the ancestors, and it is introduced by the nation’s council, Elders Council, Youth Council, and Technical Review Team. Before the reader even gets to the table of contents, there are two facing pages that explain the two clans of the nation and feature the writings of Kwanlin Dün poet Sweeney Scurvey and the artwork of Kwanlin Dün artist Dr. Ukjese van Kampen. The latter’s work can be found throughout the book and, as explained on the verso of the title page, van Kampen’s work is part of an attempt to revive the geometric period of Yukon Indigenous art that dominated the area prior to contact. Continuing this focus on authenticity, the book is divided into six seasons starting with a spring long ago and ending with the late summer, something rather like a stereotypical pan-Indian medicine wheel.

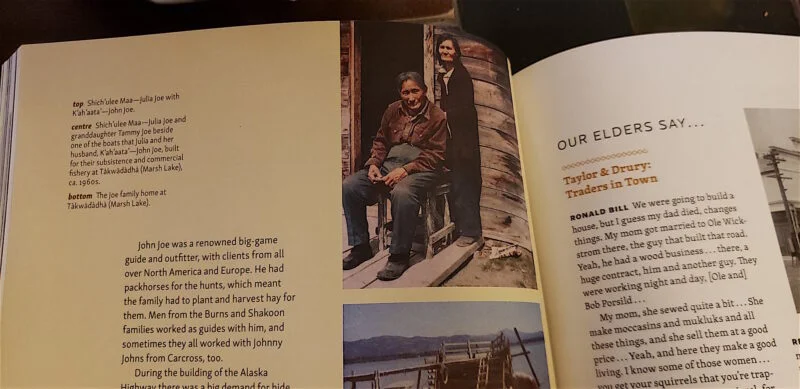

Given the breadth of time it embraces, Kwanlin Dün does not have an overarching, all-encompassing argument per se. That being said, the book focuses on community continuity, change, and survivance. The first two chapters deal with history before contact with Europeans, followed by a chapter and a half discussing the impacts of contact and Kwanlin Dün responses, and then two and half chapters covering how these responses started to see fruition in the 1970s. Starting in the third chapter are sections that document the history of certain families.

A superficial skimming of the text might result in accusations of Whig history, and certain critics might also take issue with the fact that the authors do not discuss things commonly found in grand narratives of colonialism and Indigenous history in Canada. For example, rather than spending time on things like the Pass System, which was not really implemented outside of the Prairies, or the Numbered Treaties, which did not include Kwanlin Dün territory, the text deals with the Kwanlin Dün history and its specifics.

As such, it is the Klondike Gold Rush in the 1890s and Alaska Highway and the post-Second World period that are presented as key turning points in the nation’s history, rather than first contact. Similarly, Kwanlin Dün spends a significant amount of time on the land claims process in Yukon and does not entertain recent rhetoric that the modern agreements are either not treaties, or that they are extinguishment titles, which are categorically worse than the historic treaties.

In my experience as someone who regularly teaches Indigenous history at a university level, there are certain people who like grand narratives and hate specific details or exceptions. This book is not for them. Aside from acknowledging that the modern Kwanlin Dün Nation has members from other communities, the text is only concerned about the rest of the world and other Indigenous groups if they matter to the Kwanlin Dün experience. Indeed, if there is one weakness to the book, it is that its focus on the nation might lose some readers. For example, starting in the third chapter there are sections on specific families. While key to recognizing prominent individuals and helping community members connect with the book, the importance could potentially be lost on readers not from the community.

That being said, given the intended audience of Kwanlin Dün, that is the problem of those readers. I myself liked trying to figure out if I, or anyone I knew, had any family connections to the community, and from a pedagogical perspective one could easily see students using these sections to either give reports on the individuals included, or learn from their family members about ancestors who were not included. In a similar vein, the fact that the first chapter records five oral histories in one of the languages of the nation, and then provides both literal and conceptual translation, leaves no doubt that it intended to help language learners as the community works to revive and preserve their languages.

Overall, I would recommend this book highly to anyone interested in the Kwanlin Dün, the specifics of Indigenous history in Canada, or Yukon history in general. The numerous sections and sub-sections, combined with appealing images and artwork, make the book highly approachable, as does its everyday language. Beyond this format, the text forefronts the oral history of the community, while at the same time providing context through explanatory sections.

As an Indigenous historian, I am excited to see some many communities produce history books on their own terms, and I hope to see many more.

*

A member of the Tsay Keh Dene First Nation in British Columbia, Dr. Daniel Sims is currently employed at the University of Northern British Columbia as the chair of the Department of First Nations Studies. His research primarily focuses on the Indigenous history of northern BC with a particular emphasis on the law, environment, and economy. Currently he is working on two projects. The first consists of turning his dissertation on the impacts of the W.A.C. Bennett Dam on the Tsek’ehne into a book, while the second examines concepts of wilderness and the numerous failed developments in the Finlay-Parsnip watershed of northern BC during the early 20th century. He is also working an English translation of Einar Odd Mortensen’s book, Pelshandleren: Mitt liv blant Nord-Canadas indianere 1925-28, with Dr. Ingrid Urberg, which is forthcoming from the University of Alberta Press. Editor’s note: Daniel Sims has previously reviewed books by Bob Joseph, Mary-Ellen Kelm and Keith D. Smith, and Lillian Sam and Frieda Klippenstein for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster