#976 Seeing past the mushroom cloud

The Bomb in the Wilderness: Photography and the Nuclear Era in Canada

by John O’Brian

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2020

$32.95 / 9780774863889

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Seeing past the mushroom cloud: A deeply passionate study of how photography has shaped our view of the Bomb.

Seeing past the mushroom cloud: A deeply passionate study of how photography has shaped our view of the Bomb.

*

Years ago on a visit to China, an old man taught me that I needed to look more deeply into the water below if I wanted to see the fish. Now John O’Brian has done me the same service regarding how I look at the atomic age.

Art historian O’Brian has brought together all his powers of observation and perception to help us rethink how we view the history and the mystery of the bomb. He guides us on a photographic tour from the horrifying explosions in 1945 to the atomic sabre rattling of the Cold War to the Cuban Missile Crisis that brought us to the brink of nuclear war.

This is a frighteningly honest tour of Canada’s sometimes-untold role in developing the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We meet some of the politicians — Conservative prime minister John G. Diefenbaker as well as Liberal PM Pierre Trudeau — who were complicit in U.S. nuclear arms efforts. We also meet some of Canada’s best-known war historians and learn how they played down Canada’s atomic role.

C.P Stacey in Canada and the Age of Conflict declares that Canada had “comparatively small involvement,” whereas O’Brian suggests that the historian’s “unwillingness to acknowledge Canada’s part in building the bomb contradicts the historical evidence.” Donald Creighton in The Story of Canada also fails to mention this role, including the damage done to First Nations people from uranium extraction. O’Brian calls this negligence “a form of blindness.”

A full chapter on “Atomic Soldiers” reminds us that the Rand Corporation’s Herman Kahn assured doubters that a nuclear war was “winnable.” Meanwhile nuclear workers would die of radiation exposure. Another chapter on “Mass Protest” brings us to the frontlines with photographs of the 1971 launch of Greenpeace. Protesters exposed themselves to danger at Amchitka, Alaska. Others fought against decisions like allowing the testing of the Cruise missile in Canada.

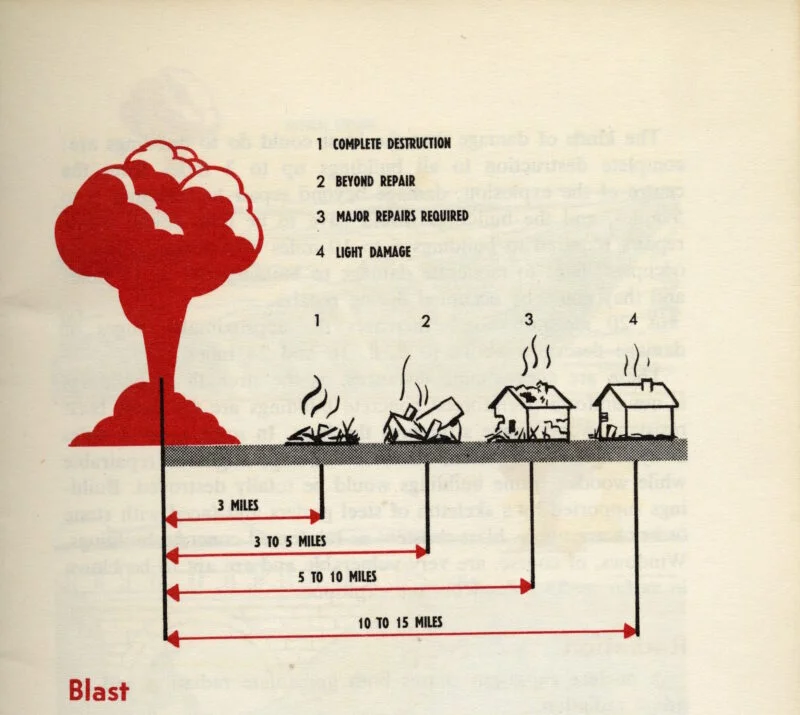

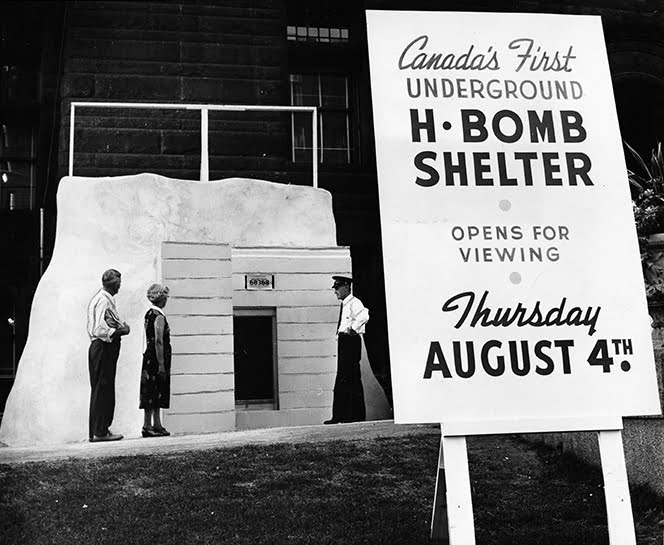

In this visual journey, we see what photographers saw, but O’Brian’s strong narrative helps us understand what they intended with their shots. At first glance, it is not always clear. Some of the images, almost all of which are in black and white (because “it carries more emotional weight than colour”) are of deserted places, destroyed landscapes, nondescript buildings, nuclear PPE, or technical laboratories. O’Brian shows us how to see inside in our search for meaning.

To do this he borrows from a range of other art forms. Novelists like Kurt Vonnegut and Douglas Coupland assist. So do Group of Seven member A.Y. Jackson and Vancouver poet George Bowering. Filmmaker Stanley Kubrick with his film Dr. Strangelove plays his part, as does Hiroshima author John Hersey. O’Brian even taps into monster fear with Godzilla and comedy shows like Saturday Night Live to collaborate in explaining the true madness of nuclear war:

The producers of magazines, record album covers, advertisements and souvenirs helped to domesticate the bombing, as did American, Canadian, and other governments that wanted to create a “comfort level” around it. Artists tried to unsettle this process of domestication.

Part of O’Brian’s job was to focus away from the ubiquitous souvenir images of the mushroom cloud and dig down into the lives of people who were hurt by it.

O’Brian also calls intellectuals into service, Susan Sontag, with whose analysis of photography he disagrees, is one example. Postmodern French philosopher Jacques Derrida is another. O’Brian uses Derrida’s poststructuralist thinking repeatedly to guide the reader through the photographs. Political theorist Hannah Arendt adds to the discussion on generational gaps in nuclear experience.

But most of all, O’Brian gives us new vision and insight through the lenses of his chosen photographers, the people who provide “a critical alternative to mushroom cloud imagery.” Most prominent among them is Robert del Tredici whose 1987 book At Work in the Fields of the Bomb “aims to reveal what nuclear authorities have kept hidden since the birth of the bomb.”

There is much more here: A few nuclear test secrets, more than a few atomic mistakes — Chernobyl, Three Mile Island, Fukashima Daiichi. There is plenty to think about as we watch, wait, and try to see deeper into an uncertain nuclear future. O’Brian’s book helps us see the nuclear fish.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and filmmaker whose short film Codename Project 9 documented the role the smelter at Trail, B.C., played in the Manhattan Project. See here for a review by Mike Sasges of his book Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh’s recent contributions to The Ormsby Review include books by Scott Stephen, Christine Hayvice, Keith Powell, Tony McAleer, Norm Boucher, Ron Shearer, and the Graphic History Collective.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “#976 Seeing past the mushroom cloud”