#973 Barman’s BC fundamentals

On the Cusp of Contact: Gender, Space, and Race in the Colonization of British Columbia

by Jean Barman, edited by Margery Fee

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2020

$34.95 / 9781550178968

Reviewed by Robert Hogg

*

Editor’s note: The West Coast Book Prize Society announced on April 8, 2021, that On the Cusp of Contact: Gender, Space, and Race in the Colonization of British Columbia, by Jean Barman, edited by Margery Fee, has been shortlisted for the Bill Duthie Booksellers’ Choice Award in the 2021 BC and Yukon Book Prizes. Winners will be announced on Saturday, September 18th, 2021 — Richard Mackie

*

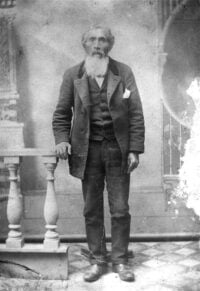

Jean Barman believes that “The past cannot be undone, but it can be redressed.” This is the task she set herself as arguably British Columbia’s most eminent historian. Over the last fifty years, Barman’s output has been prodigious. She is the author of fifteen books including The West Beyond the West, which became the standard text on the history of British Columbia; Abenaki Daring; and the evocatively titled The Remarkable Adventures of Portuguese Joe Silvey. In between these monographs, she has published numerous scholarly articles, sixteen of which have been collected and edited by Margery Fee in this volume. Barman began her academic career at Macalester College in Minnesota where she studied international relations and history. True to the peripatetic habits of American students she went on to Harvard for an MA in Russian studies and then moved to the University of California at Berkley for an MLS in librarianship. In 1982 she received her EdD at the University of British Columbia.

Jean Barman believes that “The past cannot be undone, but it can be redressed.” This is the task she set herself as arguably British Columbia’s most eminent historian. Over the last fifty years, Barman’s output has been prodigious. She is the author of fifteen books including The West Beyond the West, which became the standard text on the history of British Columbia; Abenaki Daring; and the evocatively titled The Remarkable Adventures of Portuguese Joe Silvey. In between these monographs, she has published numerous scholarly articles, sixteen of which have been collected and edited by Margery Fee in this volume. Barman began her academic career at Macalester College in Minnesota where she studied international relations and history. True to the peripatetic habits of American students she went on to Harvard for an MA in Russian studies and then moved to the University of California at Berkley for an MLS in librarianship. In 1982 she received her EdD at the University of British Columbia.

In 1848 Marx and Engels wrote that, “The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles.” They were only partly right. Barman’s work has been concerned with the fundamental structural elements of society, class being only one of them. Barman’s historical concerns have been with the mutually constitutive categories of gender, race, class and sex, and the intersections and overlappings of these elements. Her work helps us understand how colonial British Columbian society operated, and gives us a template for understanding any society. Barman’s approach has been to look at families and how they were affected by, and how they affected, colonial development. She has done so from a feminist and anti-racist position, placing women and Indigenous peoples — the most disadvantaged in white settler society — at the centre of her concerns. Barman’s histories are truly “histories from below.”

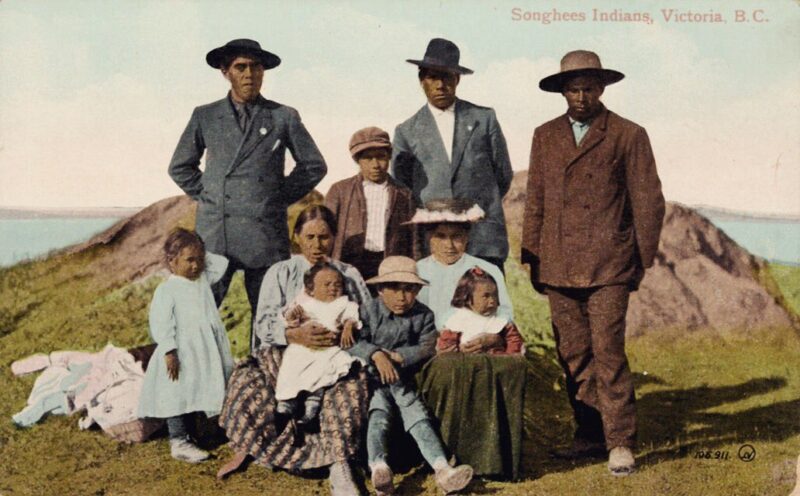

The sixteen essays in this volume are organised into four sections: Making White Space, Indigenous Women, Finding Solace in Family and Place, and Navigating Schooling. In the essays comprising Making White Space, Barman explores how Indigenous peoples were made to disappear from Victoria and Vancouver when white colonists wanted their land. In the 1890s the white burghers of Victoria coveted land long inhabited by the Songhees (now known as the Lekwungen), across Victoria Harbour from the Legislature. It is in this episode that Barman shows us how race, sex, and gender were fundamental to the struggle for control of this land. The removal of the Songhees was justified on two grounds. Firstly, it was supposedly for the Songhees own good. Living so close to the white newcomers they were subject to the worst evils of white society and consequently the tribe had become “the most degraded on the whole island.” In other words, the Songhees had to be removed because whites were a bad influence.

Secondly, the public profile of Songhees women gave the self-appointed white guardians of morality sleepless nights, worried as they were that the women were engaged in illicit and immoral behaviour and “vicious customs,” that is, prostitution. Victoria’s white businessmen ultimately got what they wanted, but not before the Songhees chief, Michael Cooper, cannily negotiated a payout of $265,000 in today’s dollars for each Songhees family, demonstrating that while Indigenous people were usually in a position of subordination, they had the capacity to resist white domination and obtain for themselves just compensation for their subjection.

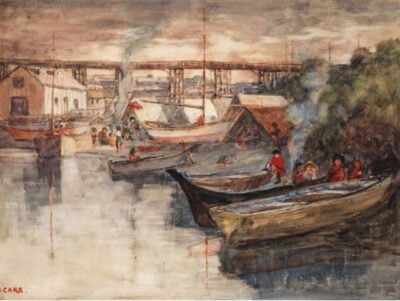

The Indigenous families who lived on what is now Kits Point, across False Creek opposite Vancouver city, were not so fortunate. They received a paltry amount and were relocated to already occupied reserve lands across Burrard Inlet. White newcomers were, however, hard to satisfy. During the 1920s and 1930s, they hungered after the land that became Stanley Park. In 1923 the BC Supreme Court dispossessed Stanley Park’s Squamish residents. Others, who lived at Brockton Point, were forced out in 1931. Not only were the Squamish and Musqueam peoples who had considered the area their home for generations physically erased, but all memory of them was also erased. The only indigenous presence left in Stanley Park was a collection of totem poles from the north coast. In the minds of the whites, one Indigenous artefact was as good as another, one group the same as another.

Sexuality, gender, and power are the key themes in the second group of essays, Indigenous Women. In these essays Barman shows how Indigenous women were almost always regarded as prostitutes, even though many of them engaged in commerce and trade. The hypocrisy of white men is exposed: on the one hand they were concerned with respectability and morality; on the other they wanted the business the dance halls, in which indigenous women worked, generated. The ultimate goal was to remove Indigenous women to distant reserves where their behaviour could be controlled. All aspects of Indigenous life were sexualised in order to justify in moral terms the subjugation of Indigenous women and their culture. Particularly fascinating is the story of Sophie Morigeau, a mixed race woman, highly literate, who accumulated considerable personal wealth as a free trader outside of the Hudson’s Bay Company; traversing northwestern North America, running pack trains to feed hungry goldminers, trading furs, whisky, cattle and horses. If a miner wanted it, Sophie could supply it. In doing so, she resisted social expectations and constructed multiple identities contingent upon prevailing circumstances.

The third group of essays is titled Finding Solace in Family and Place. Colonial British Columbia was indeed multicultural. In addition to whites and Indigenous peoples, Chinese and Hawaiians settled there, and their stories and their relationships with place are told here. Hawaiians (known as Kanakas) had crewed on the ships that took furs to China, or were recruited by the Hudson’s Bay Company prior to the establishment of the border between the United States and British North America. Many stayed and partnered with Indigenous women. Some merged into white society, while intermarriage meant a degree of ethnic cohesion was maintained. William Naukana and Johnny Palua settled on Portland Island and Johnny married William’s second daughter Sophie. William’s third daughter Julia married George Shepard, who was the son of an American who settled on Vancouver Island and an Indigenous woman. Anglo, Hawaiian, and Indigenous identities intertwined, and thus were new families formed, contributing in many ways to the settlement of British Columbia.

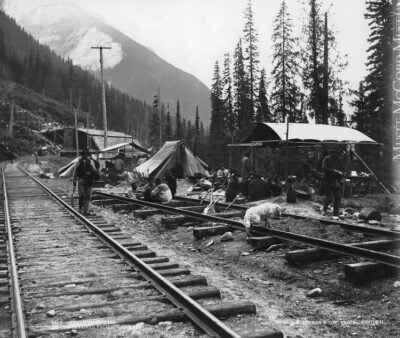

The “intertwining” of Chinese men and Indigenous women also resulted in new family formations. Barman considers the lives of Chinese men outside of the established Chinatowns of Victoria and Vancouver. The lives of these men differed from those who lived in the Chinatowns. The first wave of Chinese arrived in BC for the 1858 gold rush, and a second wave were hired to build the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s. Chinese men were subject to a number of legal constraints designed to minimise their presence, and Chinatowns offered a degree of protection from the discriminatory practices of white society. However, a small number of Chinese chose to live outside of the Chinatowns and it is their lives that Barman investigates. She finds that one in six Chinese men in early BC who had an intimate relationship leading to family formation did so with an Indigenous woman. Chin Lum Kee partnered with Lucy, a Stó:lo girl. Together they ran a store in the Fraser Valley and had seven children. In Rock Creek, Chung Moon and “Emily, an Indian woman” partnered and had a daughter, Ahn Lan. According Ahn, her father had been “a goldminer and farmer.” Emily died when Ahn was ten. Her father remarried, “according to Chinese custom,” a woman named Leng Tung Hai, worked in a sawmill, and cultivated a market garden. Like the Hawaiian families, these families defied their outsider status and led prosperous and productive lives.

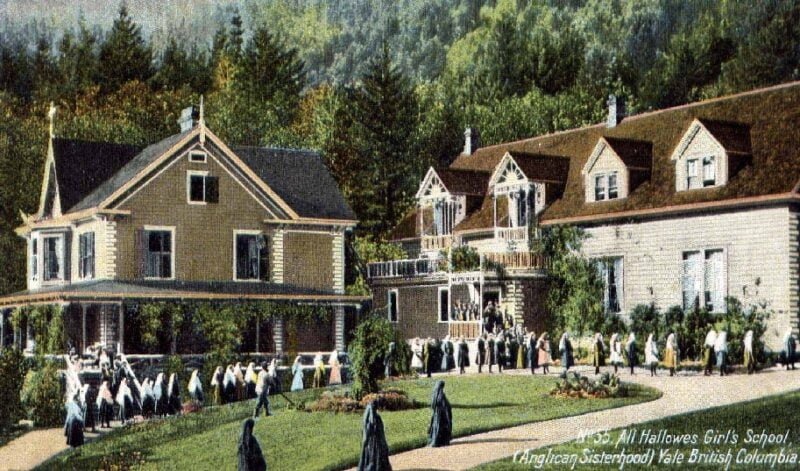

Navigating Schooling is the title of the fourth and final section, and here Barman examines the inequalities and segregation visited upon Indigenous children, particularly girls. While initially educating them together, in 1910 All Hallows School at Yale in the New Westminster diocese segregated Indigenous and white girls. The white girls were prepared for marriage, perhaps for careers, while the Indigenous girls were prepared for domestic service in white homes, ultimately to return to reserves where they would marry Indigenous men, thus being kept out of sight and out of mind. A discussion of Indigenous education is impossible without an examination of residential schools. “Schooled for Inequality: The Education of British Columbia Indigenous Children,” shows that, far from assimilating Indigenous children into mainstream society, residential schools were instrumental in their marginalisation, destroyed culture and language, damaged families, and undermined children’s confidence. Indigenous children spent less time in the classroom than their white counterparts, where taught by untrained missionaries, and the schools were chronically underfunded. As these schools were run by the various churches, the children often spent more time praying than learning.

The sixteen essays in this collection comprise only a fraction of Barman’s oeuvre, but will give the reader a comprehensive understanding of her principal concerns as an historian: the largely forgotten individuals and groups who were marginalised in white society because of their race, gender, and class. The stories Barman tells are absolutely fascinating. She has succeeded splendidly in representing the unrepresented, in redressing past omissions.

*

Dr. Robert Hogg has taught history at a number of Australian universities, primarily at the University of Queensland. He is the author of Men and Manliness on the Frontier: Queensland and British Columbia in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). He is currently researching Australian and Canadian soldiers on the Western Front. Editor’s note: Robert Hogg has previously reviewed books by Laura Ishiguro and Christopher Herbert for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#973 Barman’s BC fundamentals”

Great review. Thanks so much