#966 A torrent of collective memory

The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats

by Robert Amos

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2020

$22.00 / 9781771513364

Reviewed by Brian Harvey

*

For the British Columbia painter E.J. Hughes, who died in Duncan in 2007, the sea was never far away. Hughes wasn’t the only famous Canadian artist to include boats in his canvases — we’ll come to Alex Colville later — but he is probably the one who made the most of boats as subjects, not settings. His life and works have been celebrated in a number of books, most recently by Robert Amos in E.J. Hughes Paints British Columbia (TouchWood Editions, 2019).

For the British Columbia painter E.J. Hughes, who died in Duncan in 2007, the sea was never far away. Hughes wasn’t the only famous Canadian artist to include boats in his canvases — we’ll come to Alex Colville later — but he is probably the one who made the most of boats as subjects, not settings. His life and works have been celebrated in a number of books, most recently by Robert Amos in E.J. Hughes Paints British Columbia (TouchWood Editions, 2019).

If you live in British Columbia, especially on the coast, there’s a good chance you’ve had what I’m going to call an “E.J. Hughes Moment.” Mine came eight years ago, when I moved from Victoria to Nanaimo. I brought with me a framed print of Nanaimo Harbour, which Hughes painted in 1962 from sketches he’d made from the window of the Malaspina Hotel in 1948. Notice the hiatus between sketch and painting, a characteristic I’ll return to. I owned the print simply because the painting was a knockout, featuring not one but two of the grand old Canadian Pacific steamships serving the Victoria-Vancouver-Nanaimo triangle. The brilliant white of their superstructure pops out against the aching, late-afternoon blue of the harbour and is echoed in the snow on the Coast Range mountains across the Salish Sea. In our new place on Protection Island, the painting found a natural home on a wall that received light from three sides. It looked great. It seemed happy. We settled into the new experience of commuting back and forth to Nanaimo by small boat, a distance of about half a nautical mile.

My Hughes Moment was triggered by cormorants. The big black diving birds were perched on a refrigerator-sized block of concrete emerging from the water between the seaplane terminal and the sewage pump-out station. Four long bolts stuck out of the top surface, like blown-out birthday candles, limiting the available space to a couple of cormorants and the occasional nervous-looking seagull. One night, I spotted the same block of concrete in the lower left corner of my Hughes painting, only it was topped by the elegant circular wood lattice that, back in 1962, meant “rock submerged at high tide.” Those four bolts — yes, they would have held the lattice in place nicely.

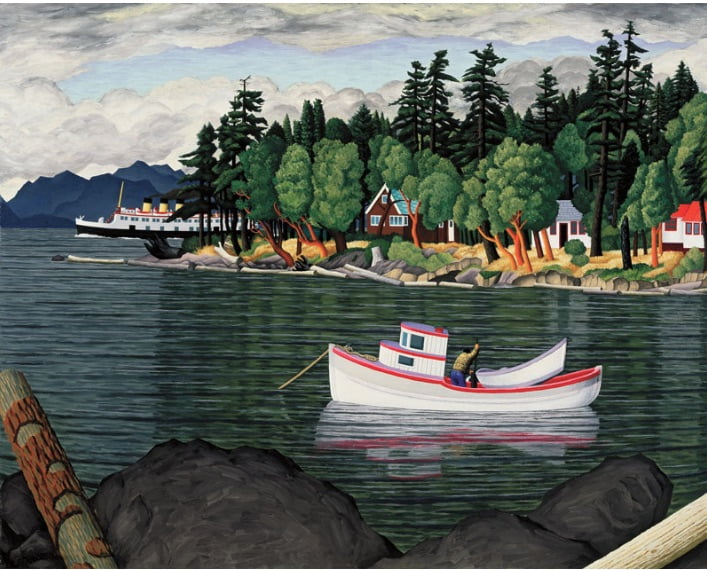

That was my Hughes Moment: every day, I was driving my boat straight through an E.J. Hughes painting. I hadn’t noticed because the harbour has changed so drastically since Hughes painted it. The only surviving landmark was that stub of concrete. Now, everything else snapped into place: pre-development Protection Island on the right, still-a-park Newcastle Island on the left, “the Gap” in between and the whale-back hump of Snake Island farther out. Every day, I was tying up right where the Princess Elaine was disgorging her passengers. Hughes had painted a wooden troller heading for the gap, where there’s seldom enough water to let such a big boat through, but he wanted him there, and that was fine with me. The painter was always fiddling with reality in his coastal scenes, another point I’ll return to later.

Of course, I am not the only British Columbian to have had a Hughes Moment. My sister lived for a time in a small waterfront cottage on Cherry Point, which she was delighted to spot, much later, in a Hughes painting. And the Victoria columnist Adrian Chamberlain has written that, for him, the painting Taylor Bay, Gabriola Island (1952) recalls the place as a “powerful dream.” Chamberlain was raised on Taylor Bay. I’ve anchored my own boat there, and it is magical. E.J. Hughes’s depiction only makes it more so. That painting, like Nanaimo Harbour, also features a gleaming three-stack Princess steamer forging out of the picture, as well as a small fishing boat Chamberlain describes as “unnaturally white, as though illuminated by a klieg light.”

*

Both Taylor Bay and Nanaimo Harbour are featured in The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats, a sparkling new release from TouchWood Editions. Nanaimo is especially prominent, appearing in paintings and sketches from 1948, 1950 and 1958 as well as in the 1962 version (the one on my wall) that also makes it onto the cover. The text is by Robert Amos, author of two previous books on the painter and currently at work on a fourth. The illustrations, which dominate the book, are mostly reproductions of major paintings, along with sketches and a few photographs, most of them taken by Hughes. When I was asked to review the book, I thought, E.J. Hughes and boats? What could be better?

Not much. The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats is handsomely designed and produced, and it’s very sensibly arranged. Just flip through it, find a picture you like and go. Agreeably sized just a bit smaller than a standard piece of letterhead, this book is no coffee-table killer. Instead, it invites you to pick it up, stick it in your bag, maybe even take it to the beach. The book isn’t a treatise on Hughes or his influences or even the methods by which he achieved such wondrous results. Amos, though himself a well-known artist with a sizeable following, wisely eschews art criticism here; in fact, the closest the book comes to technical analysis is the quote from Adrian Chamberlain on his reaction to the Taylor Bay painting. For me, experiencing the book was like strolling through an interesting neighbourhood with someone who lives there, who can point out the architectural highlights and tell the choicest stories about places and characters — an easygoing expert lobbing context at you along the way.

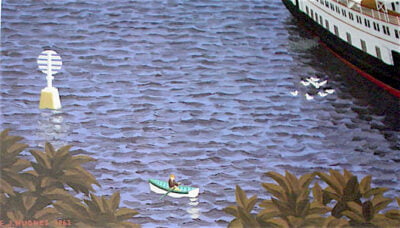

This is what Amos does in the boat book – he lets the pictures do most of the talking. It’s not the kind of book where a reviewer looks for faults in the writing, or in the writer’s arguments. In any case, there are none such in The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats. The only actual error I could find was calling the small tender in Mouth of the Courtenay River a dory, when it’s actually round-bottomed and clinker-built. That flat-bottomed, slab-sided dinghy inside the fishing boat in Taylor Bay – that’s a dory. Forget I even mentioned it.

If Robert Amos doesn’t lecture the reader about the artist and his art — something he would be highly qualified to do — what does he add to this collection of entrancing paintings? The approach he adopts is subtler and, in my view, much more effective: he increases our appreciation of these canvases by dropping hints and clues that we can, if we like, follow up. A good example of this kind of offhand explication is the sketches that accompany many of the major paintings reproduced in the book. Hughes preferred to work from sketches and photos, Amos tells us that much, but he doesn’t push our noses in the fact that the paintings very often followed years, even decades, after the sketches were done. Amos doesn’t go on about the critical differences between the two versions – admirable restraint from someone who has made his living both as an artist and as writer about art — because the evidence is there, in the dates and in the work. I got very interested in these sketches, because what they told me was that Hughes was so often painting a scene that no longer existed.

A writer can turn an old idea into a book and nobody will be the wiser, but an artist who reanimates a decades-old sketch is painting a memory. Hughes knew it, writing to his long-time agent Max Stern that, “sad to say,” the ships in his 1962 painting of Nanaimo Harbour had been retired or broken up. That harbour and the Princess Elaine, which he first sketched from the Malaspina Hotel in 1948, appear in various stages in the boat book, including a more primitively styled Steamer Approaching the Dock, Nanaimo in 1950 and again, in 1958, the scrunched-looking Steamer at the Old Wharf, Nanaimo. Hughes did the sketch for that one from the rocky knoll next to what’s now the Port Place shopping mall. Stern paid him $180 for it. There are many examples of multiple-decade gaps between sketch and painting in The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats. Mouth of the Courtenay River was done fifty years after the sketch, and Hughes alters very little. On the other hand, the fifty-eight years between sketch and painting of the fishing boats in Roberts Bay, near Sidney, brought forth riotous colours and the complete obliteration of the original background in what is quite a late picture (2006).

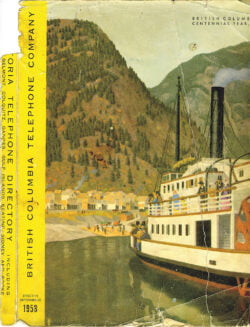

But Hughes’s work wasn’t all retrospective or confined to southern Vancouver Island. Boat-featuring works that he created on commission ranged wherever the client wanted him to go – Prince Rupert, the Broughton Archipelago, Haida Gwaii –and ranged from the present to the much more distant past. Amos tells us about the five oil tanker paintings commissioned by the Standard Oil Company in 1953 and published in 1954, but while he includes an original graphite sketch made in Echo Bay, the resulting oil tanker painting in the boat book is one Hughes did long after, in 1992. It’s an attractive watercolour but it lacks the exuberance of the Princess oils. For another commission, a cover illustration for the 1958 British Columbia Telephone books, Hughes jumped back a hundred years to recreate a gold rush scene on the Fraser River, complete with paddle-wheeler, from “photos and costume notes.” And of course his 1966 commissioned painting of the HMS Discovery and HMS Chatham, Captain Vancouver’s famous ships, could only follow the work of eighteenth century artists.

What may be his best-known commissioned work contains boats of several sizes but for some reason did not make it into The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats. Its story takes us back to the Malaspina Hotel, from which Hughes made his 1948 sketches of Nanaimo Harbour. A decade earlier, the painter had contributed a mural to a series commissioned by the hotel. Hughes’s effort, which was walled over during a subsequent renovation, depicted the hotel’s namesake, the Spanish explorer Alejandro Malaspina, sketching the baroque sandstone formations on neighbouring Gabriola Island, a geographic feature now known as the Malaspina Galleries. Hughes has his man in full explorer fig as he creates his Instagram for 1791: frockcoat flowing, buckled shoes firmly planted on the pebbles, pencil poised. The mural resurfaced in 1996, when the Malaspina was demolished so that a great wedding-cake condo complex could be erected in its place. After much painstaking restoration, it’s now re-exhibited just down the road in the Vancouver Island Conference Centre. The painting is in heroic style and to my taste uninteresting. The depiction of actual people disappoints. (There are few portraits in the boat book, an absence I hope will be offset in Robert Amos’s forthcoming book on Hughes as war artist.) Of the indigenous owners of the beach Malaspina and his men are occupying there is no trace, although, to give the explorer credit, he was an outspoken critic of the Spanish colonial system within which he worked. Too outspoken, as it turned out: King Charles IV jailed him for six years for his views.

*

What is it in Hughes’s paintings of coastal scenes that so strongly touches so many people? And why is that “Hughes Moment”, when you realize you’re standing in a Hughes painting, so satisfying? After all, many people find themselves walking through places featured in famous paintings. In most cases, though, the realization is academic, not visceral. Parisians may have their own “Seurat Moments” or “Toulouse-Lautrec Moments”, but I bet they’re not as vivid as an “E.J. Hughes”. After reading and re-reading Robert Amos’s book, I think the reason lies in those wrinkles and stretches and inspired tweaks that Hughes worked on his original sketches (we’re back to those sketches again). The best of them are near-photographic in their level of detail; for most people, capturing a scene like the sketch Hughes did of Echo Bay in 1953 would be achievement enough. But really, what’s in that sketch is what you or I might see if we sat beside the artist on his log, or on the front seat of his car, or at the window of the old Malaspina Hotel: a pleasant place to unwrap a sandwich. For me, a Hughes sketch is like an assortment of chemicals in their labelled bottles, before the alchemist goes to work, and it’s the alchemy of E.J. Hughes, that unknowable process, that transformed charming sketches into paintings that will stop you in your tracks. Those paintings get to us because Hughes could see what we can only feel. When he transmuted his vision into art, the effect on a viewer, especially one who has actually been to the place depicted, is a sense of identification that’s downright spooky.

You could spend hours comparing a Hughes sketch with the resulting painting. The sketches delight and intrigue, but the paintings grab. Ferries get stubbier. Fishboats acquire paint jobs no commercial fisherman would have been able to afford. Islands expand, contract, glide around. Mountains creep closer. Water surfaces became roiled and ruffled or glassy calm – sometimes all three, and it still works, because Hughes knew a local bay could do that. Big boats steam too fast, and too close to shore, but who wants to see the Princess Victoria doddering along at five knots? In every case, Hughes took the meticulously recorded information out of a sketch and brought it to the kind of joyous life that viewers connect with, instantly. It’s real, but it’s not, and that’s its strength. Look at the 1948 sketch of tugboats and a log boom, then at the 1949 painting Logs, Ladysmith Harbour. The tugs, perfectly normal in the sketch, are actually going uphill now as though driving up a dazzling river. After I’d pored over a few of these pairings, I found myself wondering about Hughes himself. There are a few photos of him in the book, but he always looks the same: neat, conservative, maybe a little fussy, essentially static. He looks like one of his sketches. Was there another E.J. Hughes, bright-coloured and belching smoke, going full speed inside?

But The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats is not about Hughes and his creative process, at least not overtly. It’s about boats. On the evidence of the pictures included in this book, E.J. Hughes couldn’t keep his eyes off boats. Boats on the water, boats flipped upside down on the dock, even boats in boathouses. Shape, size, purpose — none of these seemed to matter to him. He painted canoes, lots of rowboats, runabouts. Wooden seiners and trollers have an obvious place in his heart, as do the car ferries that have long served the smaller island routes (if Hughes ever painted the behemoth replacements for the Princess ships that used to do the major runs between Victoria, Vancouver and Nanaimo, they’re not in this book). He did freighters too, with their masts and cranes like chopsticks stuck rudely into rice. In Nanaimo-Bound Freighter, a watercolour looking north from Gabriola Island, the sea is glassy and the freighter, dark against the sunset, exits stage left.

On the evidence of this book, though, Hughes seems to have been most smitten by the Princesses of the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company. Here they are, Victoria, Adelaide, Elaine, even Mary, whose superstructure became a much-loved restaurant in Esquimalt. Hughes lifted his hat to them in ports and in passes — wherever he could spot them from land. Early in his career he adopted for these ships the fevered, neo-primitive style seen in Coast Boats Near Sidney (1948); later, the Princesses swept stylishly through more realistic backdrops or even, as was the case for The Coastal Steamship Princess Victoria (1965), against a completely made-up one. She’s going full speed and cutting awfully close to shore. Needless to say, there are two much smaller boats in the picture, a gillnetter and an outboard putt-putt that’s about to get swamped. The captain and his passenger are about as large as people get in Hughes’s boats, which is to say, quite small. Unlike Hughes’s near-contemporary and fellow war artist Alex Colville, who featured boats in many of his paintings, Hughes let the boat itself be the story. Colville’s famous painting To Prince Edward Island, in which a woman stands on the deck of a ferry, isn’t about the ferry. It’s about the woman, and the enigmatic binoculars that hide half her face (she was Colville’s wife, Rhoda).

Where boats were concerned, and this is the part I liked most about the book, Hughes turns out to have been much more than an uninvolved recorder of attractive shapes. Both in his notes and in his selection of paintings, Amos makes it clear that Hughes knew boats. He owned several himself, and not just for pleasure. The Burma (shown in a photograph) was an inboard-powered workboat, ferrying Hughes, his wife, and their groceries across Shawnigan Lake every week. The slicker Peterborough runabout that followed Burma appears in two paintings in the book, although not as the main subject. One, called Old Baldy Mountain, Shawnigan Lake (1961) looks out over the runabout’s bow; the other, Entrance to West Arm, Shawnigan Lake (1960), features his wonderful Johnson Seahorse outboard, with its rounded corners and white decorative fins, in the foreground.

This is exactly how boaters see their own boats: always part of the picture. Every time a pleasure boat zipped through a harbour scene in The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats I couldn’t help thinking, there goes Hughes in his Peterborough. And to dispel any suspicion that the artist was just a weekend boater on lakes, the riotous Fish Boats, Rivers Inlet (1946) leaves no doubt that the young Hughes put in hard time in boats: in 1937 and 1938, Amos tells us, he fished commercially in Rivers Inlet, an unforgiving fjord on the British Columbia mainland coast, between Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii. When Hughes painted anything smaller than a ferry, he knew how it felt under his feet, in his hands, on his face.

*

The art of E.J. Hughes is internationally known, and it would be laughable to say you have to live in coastal British Columbia to appreciate it. But it’s not laughable to say that British Columbians can enjoy a special jolt. For people like me, and for many, many others, the works of art so impressively presented in The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats will release a torrent of collective memory, like a spillway opened in a dam. We’re living in a miserable time. Thanks to Robert Amos and TouchWood Editions, we can, if only briefly, go back to a better one.

And what about that chunk of concrete in Nanaimo Harbour, the object that triggered my own Hughes Moment? It’s still there, still glued to the nasty rock that emerges, dripping, once a day, but its warning function has been officially seconded to a corral of four equally spaced cardinal buoys. A cardinal buoy is an ugly thing, topped with a pair of black triangles in one of four orientations (one for “North is safe,” one for “South is safe,” you get the idea). They look like mismatched Bishops surrounding a beheaded Pawn. Who needs them? The Princess Elaine managed to avoid that rock without cardinal buoys, and no ship anywhere near her size docks there anymore.

I know what I think of those cardinal buoys, just as I know what I think of the ships that dock in the Port of Nanaimo now. Many of them abscond with raw logs, taking local jobs with them. Another, the 200-metre Tranquil Ace, disgorges a stream of new Mercedes-Benzes every couple of months. It looks like a milk carton. I doubt if E.J. Hughes would have bothered to paint it.

*

Brian Harvey grew up on the West Coast of Canada and trained as a marine biologist. He began writing newspaper columns and science-travel articles for magazines in 1997. His first book for a general audience (The End of the River) was a Globe and Mail “Best 100” book for 2008 and was followed by two works of fiction (Beethoven’s Tenth and Tokyo Girl). His latest book, Sea Trial: Sailing After My Father, was a 2019 Governor General’s Award finalist for nonfiction and an Independent Publishers Book Awards medalist in the memoir category. See here for a review by Theo Dombrowski. Brian Harvey has also reviewed books by Sam McKinney and Alex Zimmerman for The Ormsby Review. He lives in Nanaimo.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “#966 A torrent of collective memory”