#958 In with civility, out with vitriol

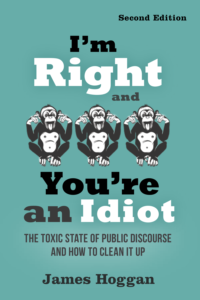

I’m Right and You’re an Idiot: The Toxic State of Public Discourse and How to Clean it Up

by James Hoggan with Grania Litwin

Gabriola: New Society Publishers, 2019 (second Edition, first published 2016)

$19.00 / 9780865719149

Reviewed by Logan Macnair

*

That the public discourse surrounding certain social and political topics (particularly in online spaces) is something of a distressing mess is not a claim I suspect many would disagree with. It’s an easy, almost clichéd assertion to make that anyone with a working Internet connection can likely verify. What’s much more difficult is to attempt to explain how and why things got so bad in the first place, and more importantly, what potentially can be done to elevate public discourse above its current state of unhelpful antagonism.

That the public discourse surrounding certain social and political topics (particularly in online spaces) is something of a distressing mess is not a claim I suspect many would disagree with. It’s an easy, almost clichéd assertion to make that anyone with a working Internet connection can likely verify. What’s much more difficult is to attempt to explain how and why things got so bad in the first place, and more importantly, what potentially can be done to elevate public discourse above its current state of unhelpful antagonism.

Nonetheless, this is exactly what James Hoggan attempts, and largely succeeds, in doing in I’m Right and You’re an Idiot: The Toxic State of Public Discourse and How to Clean it Up. Hoggan does this partly by presenting some of his own perspectives and rich experiences relating to the topic of public discourse, but his primary role with this book is to compile, organize, and succinctly present the opinions and insights of the two dozen or so individuals he interviews about the current troubling nature of public discussion.

A few exceptions aside, the bulk of the book’s chapters are framed around these various discussions Hoggan has with individuals from a diverse range of backgrounds (academics, psychologists, activists, environmentalists, journalists, religious leaders, and more), including several notable public figures such as Noam Chomsky, Thich Nhat Hanh, and the Dalai Lama. These people present their own unique takes on the state of modern discourse, and in most cases, offer some combination of explanations and possible solutions for understanding and addressing the issue.

Throughout these discussions we are introduced to concepts such moral matrixes, cognitive dissonance, social pathologies, confirmation bias, algorithms, gaslighting, psychic numbing — among others — all of which are presented as potential reasons as to how and why modern debate, discussion, and disagreement have become increasingly vitriolic and ineffective.

Even more interesting (and often overlooked) are the various solutions presented by Hoggan and his guests with respect to how to “undo” or otherwise heal the damage that has been done to public discourse. These solutions range from changes that can be taken at the smallest, most individualized level, right up to challenging the large-scale structural conditions and corporations that are thought, to some extent, to be responsible.

Several of Hoggan’s interviewees believe that this change can only truly start from within each of us as individuals. They encourage the importance of empathy, honesty, connectedness, self-awareness, and active listening as means to foster more respectful, fruitful, and effective discussion. A recurring theme is the potential value of interpersonal communication, even when it involves people whose ideas we may strongly disagree with.

Several of Hoggan’s guests remind us that disagreement itself is not inherently problematic; rather, it is only when we allow this disagreement to feed feelings of self-righteousness or even hatred that the public discourse begins to suffer. The solution, then, is to be true to your convictions, while at the same time keep a more open and empathetic mind, or as renowned Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh advises Hoggan, “speak the truth, but not to punish.”

Other figures that Hoggan speaks with point out and seek to challenge the role and influence that various social media platforms, propaganda networks, tech companies, and special interest groups are thought to have in further widening the schism between people by spreading misinformation and fostering further confusion, disagreement, and mistrust. And certainly there are compelling arguments made here with respect to the need for a greater public awareness of just how much of the media content and ideology that individuals are exposed to are purposely dictated by these various mediums and their algorithms.

Most of the discussions and interpretations of public discourse in the book are centred around the issue of climate change, which is understandable given Hoggan’s extensive background and familiarity with the topic. However, this book could be considered something of a missed opportunity to examine further the state of modern online discourse, particularly amongst younger generations and the social, cultural, and political topics that resonate the most with them, bearing in mind that climate change tends to be a less divisive topic for younger people, regardless of their political orientation. Either way, the emphasis on climate change discussion does not really detract from the points or arguments the book is putting forward, as they are typically easy enough to translate to the various other “hot topics” of modern discourse.

Hoggan himself makes no attempt to hide where he stands personally on the various issues being discussed, most prominently climate change — and nor does he need to. One of the fundamental arguments he makes in I’m Right and You’re an Idiot is that people should be more open and transparent about where they stand and what agendas they might have. Were Hoggan to have attempted to hide his own perspective or adopt a more neutral approach, he would have betrayed his own worthwhile advice. Rather, he lets his positions be known openly while encouraging others to do the same in the interest of encouraging more honest and worthwhile interactions within public discourse.

Hoggan’s writing style is at once intimate, organic, informative, and largely persuasive. He seamlessly blends his primary arguments with metaphors, personal stories/anecdotes, and the insights of the various individuals he speaks with in an effective and natural way. This style, combined with the relatively short and digestible nature of the chapters, made for a reading experience that was both enjoyable and informative, which is not always an easy balance to achieve and maintain.

And perhaps most crucial to the effectiveness of this book is that while many of the interviewees discuss and outline the truly alarming and seemingly insurmountable amount of power and influence that propaganda networks, algorithms, lobbyists, social media platforms, and other structural interests have in shaping and manipulating public discourse — typically for the worse — Hoggan never seems to adopt or encourage the attitudes of pessimism or defeatism, choosing instead to remain solution-oriented and hopeful about a brighter future he believes to be possible.

This is a welcomed perspective, and a reassuring one given that Hoggan himself, even after all of his experience studying and following the gradual decay of public discourse and seeing the worst of it firsthand, still seems to earnestly believe it. Hope, we learn from one of the early conversations in the book, “is the narrative of freedom and change.”

On that note, it seems fitting now to end on one of the main arguments of the book, presented here in a simplified and paraphrased form:

In a world where technology has given everyone an equal voice, where everyone has the opportunity to project their voice to the entire world, and when never in all of human history has it been as easy as now to have yourself heard, one of the bravest things you can do is step back and try to listen earnestly and empathetically to others.

*

Logan Macnair (PhD) is a researcher, instructor, and novelist currently based out of Burnaby. His academic research is primarily focused on the online narrative, recruitment, and propaganda campaigns of various political extremist movements. His debut novel Panegyric was released in 2020 by Now Or Never Publishing (reviewed here by Eryn Holbook). He has recently completed his second novel, Troll, which is a fictionalized account based on his many years of studying online extremist groups.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#958 In with civility, out with vitriol”