#948 Down and out at Main & 6th

Notice

by Dustin Cole

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2020

$21.95 / 9780889713840

Reviewed by Brett Josef Grubisic

*

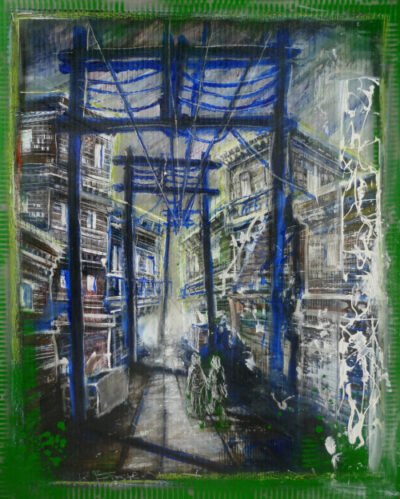

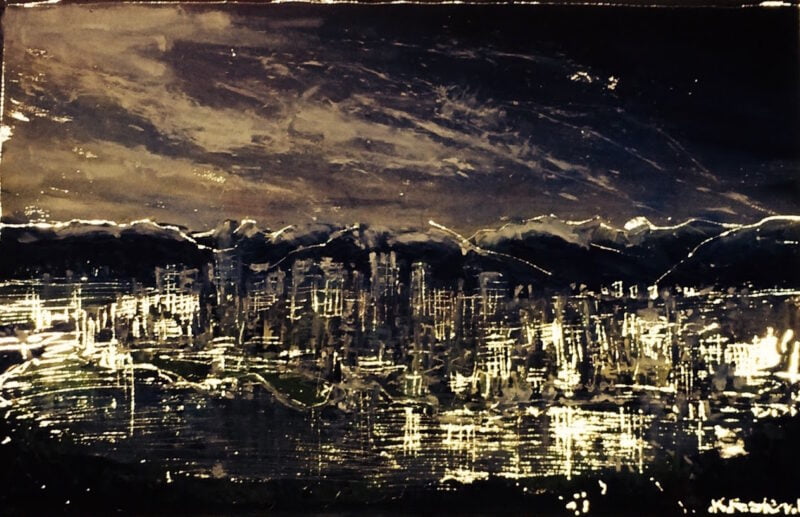

Early in Dustin Cole’s audacious and emphatically atmospheric debut novel, Levett, Cole’s furious flaneur of an anti-hero, catches a glimpse of himself: he takes in his pouched eyes and frazzled hair. Minor indignities, they’re practically the least of his worries. For one, the weather’s intrusive and abysmal: either hostile with incessant pissing rain in Vancouver’s spring or, months later, over the summer of 2017, an ominous season of choking smoke from distant wildfires: “Through rust-coloured air, the vulcanized land evoked a planet in the hot tumult of its own creation.”

Early in Dustin Cole’s audacious and emphatically atmospheric debut novel, Levett, Cole’s furious flaneur of an anti-hero, catches a glimpse of himself: he takes in his pouched eyes and frazzled hair. Minor indignities, they’re practically the least of his worries. For one, the weather’s intrusive and abysmal: either hostile with incessant pissing rain in Vancouver’s spring or, months later, over the summer of 2017, an ominous season of choking smoke from distant wildfires: “Through rust-coloured air, the vulcanized land evoked a planet in the hot tumult of its own creation.”

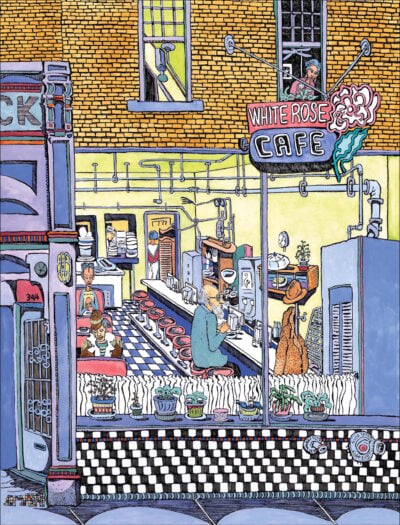

Still, weather’s relatively only an irritant, a buzzing fly. Far worse, since graduating with a History degree, Levett has taken entry level jobs by the handful, the current one a “dish-pit gig” that pays about twelve hundred a month. In a “deep ditch of insolvency,” the no longer young man has massive student loans, defaulted debts on credit cards, and myriad personal IOUs all over the city. Though necessary, intermittent monetary gifts from his mother in Northern Alberta are corrosive to his self-esteem. To cut costs, meanwhile, Levett piggybacks on a neighbour’s wifi network (while taking baths in the dark of a fetid bathroom: BC Hydro has cut his power for non-payment) and shoplifts frozen meat pies when his bank balance dwindles to forty-eight cents.

As Levett wanders the streets across the novel’s three parts (III: Event; II: Pause; I: Exit, in that order), he routinely runs into further grating problems: other creatures, both alive and dead.

The guy in the car blocking the sidewalk, for instance:

All the love inside drained away. All the hate rose up. ‘Look, motherfucker, you’re on your phone, you’re in the way, and you don’t give a shit. Why don’t you step out of your box for two seconds, come outside your pill of a life and consider the world around you? Your lapdog with its peanut brain and blind devotion shows more humanity than you do with your ass behind the wheel of this stock ride.’

A homeless man:

A man approached pushing a plastic shopping cart, all the hard living readable in deep face-lines, his appearances an inventory of personal neglect: the illegible logo on his sweatshirt, blue jeans a glossy brownish-black, toecaps blown out, ballcap pulled low over his eyes, ashen hair, nicotine moustache, snuff-juice mouth corners. A couple of pop cans rattling around the bottom of the brittle cart illustrated his lack.

A bird:

They stepped over a dead pigeon coated with maggots, wings askew, entrails oozing from its split breast.

An everyday street scene:

Dealers, pedlars and addicts milled about in front of a wrought-iron fence topped by fleur-de-lys. A hooker slowly stepped onto the curb, her toes squeezed into a pair of high-heel sneakers. Slack belly, sore-ridden arms and thighs. It took her a number of seconds to get both feet from the street to the sidewalk. She was very stoned. Levett imagined her perceiving the surroundings as slow and receded, nearly touching her.

There’s even himself, imaginatively, in a looming future where Levett foresees only deeper humiliation and degradation:

[T]he prospect of cooking on a hot plate, showering at the YMCA pool amongst the other downtrodden men, their working and spitting, their pubic hairs, seminal fluids and mucous clogging the drains, their bad intentions and their missed opportunities, warm water well above the ankles, ringworm, dermatophytosis.

Whatever the origins of his precipitous decline, Levett’s has reached a boiling point as the novel opens; already overflowing with frustration, anger, despair, and multi-directional contempt, the latest “kick in the teeth” relates to home, humble (well, decaying) #210 in Bellevue Heights on Main Street, built in 1914. He’s gotten a sketchy eviction notice and after some advice from a lawyer friend he decides to dispute it. Will arbitration rule in his favour or not? Stay tuned!

Cole’s novel veers toward (pitch) black comedy at points, with various set pieces at drunken parties, the sweat-soaked dish pit, Kafkaesque government offices, and espresso cafes portrayed as unnerving, familiar, and amusing in equal portions. (There’s a literary equivalent to a film’s impressive single-take tracking shot too — it begins with LSD tabs and neon hallucinations, ends hours later on a “rank futon” and the discouraging words “Don’t go down on me.”)

The comedy is a relief, of course, and it’s welcome because the scenes at work, with friends and acquaintances, and the many streets in between and towers above — the affluence reflected by new buildings and flashy cars and expensive stuff — render city living through a notably dystopian lens. The inequality, abuse, exploitation, and unfairness isn’t exactly news to anyone with open eyes but tracing it through a few months of the punishing experiences of Levett (and other tenants at Bellevue Heights) grows more and more sobering and becomes profoundly disheartening. Small wonder the man seeks oblivion through narcotics and vents with outbursts of anger.

My few quibbles for the novel relate to my involvement with Levett. Cole shows little of him before the present day, and seldom gives indications about what precipitated his seemingly hopeless descent: crushing debt like $70,000 in student loans surely played a role, but for me more about what makes (and made) Levett tick would have been welcome. It could be that Cole desires for readers to consider Levett as representative, as an example of the abjection or precarity that develops when social and economic forces work in tandem to both oppress and restrict an individual, to, in this case, paint him into a corner. Still, I found myself following Levett’s interactions and bearing witness to an extraordinarily unappealing Vancouver through his eyes; but I wanted to understand Levett better, to sense his psychological workings. But that seemed outside the novel’s purview and, to a degree, denied me an empathetic reading experience.

Attentive to blight and failings and ugliness, Notice offers a unique literary experience. It won’t leave you hopeful or encouraged with its underbelly snapshots. It’s visually arresting, though, and fascinating for its choices of venue: you might not want to, but you’ll find yourself noticing Vancouver’s mean streets with greater clarity than you might have before.

*

Brett Josef Grubisic teaches contemporary literature at the University of British Columbia. He’s also working on My Two-Faced Luck, his fifth novel.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “#948 Down and out at Main & 6th”