#941 Remembering World War Two

Midnight Train to Prague

by Carol Windley

Toronto: HarperCollins Canada, 2020

$24.99 / 9781443461023

Reviewed by Sherrill Grace

*

Midnight Train to Prague is a complex narrative set during and immediately after the war with important messages for the present. It is also a compelling historical novel that is well worth reading. Against the background of the war, Windley establishes a network of interwoven love stories about loss, tragedy, grief, family and, above all, about memory. And it is this business of memory and of how Windley weaves memories together that I find fascinating. Caveat Lector: as you begin to read, pay close attention to seemingly inconsequential details such as names, brief events, and passing encounters because, like clues in a mystery novel, these details will recur and they will matter.

Midnight Train to Prague is a complex narrative set during and immediately after the war with important messages for the present. It is also a compelling historical novel that is well worth reading. Against the background of the war, Windley establishes a network of interwoven love stories about loss, tragedy, grief, family and, above all, about memory. And it is this business of memory and of how Windley weaves memories together that I find fascinating. Caveat Lector: as you begin to read, pay close attention to seemingly inconsequential details such as names, brief events, and passing encounters because, like clues in a mystery novel, these details will recur and they will matter.

The novel’s third-person narrative is divided into three parts, which remind me of a play structure. In part one we meet a group of unrelated characters, each with a complex background, from different European countries, and we gradually learn about who they are. A chance meeting on a train and a glimpse of a stranger’s car from the train window will prompt the synchronicity that eventually connects the main story lines. Part two introduces more characters and complicates the lives of these people as they are pulled inexorably through the 1930s and into the war. Part three is where we begin to see just how profoundly the rise of Nazism and the war affects the lives of the characters about whom we have come to care. Some of these people (for they are so clearly drawn that we come to see them as credible and sympathetic human beings) will die at the hands of the Nazis, or from diseases, or from combat, but others will survive to remember and share their memories with us. Watch for those simple phrases or questions — “do you remember?” or “I remember” — because they are signposts guiding you in the process of reading this novel.

The stories unfold in many places, notably in Berlin, Prague, Budapest, and a country estate in Hungary, and events occurring in one of these places will have repercussions in the others, much as they did during the war, so places must also be remembered because they too help us follow the threads being woven together by the narrator. If you have never visited Prague or Budapest or Berlin, do not worry. Windley recreates the Charles Bridge, the Berlin Tiergarten, the castles in Budapest and Prague, and the rivers that run through Eastern Europe, with such precision that it becomes easy to imagine these places. If you are not keenly interested in the history of the war, then some details may slip by you, but others, like the reign of terror in Prague and the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, are clearly set forth.

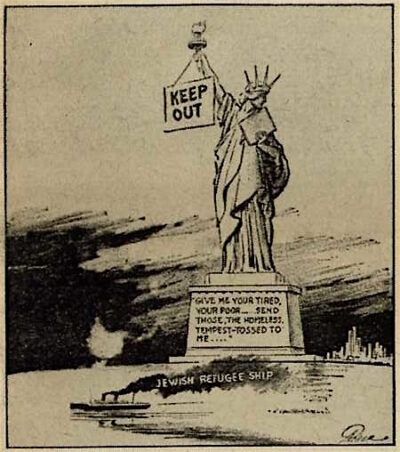

Among the small details that caught my eye was the reference to a 1939 “boat carrying a thousand Jewish refugees from Europe” (p. 283), a boat turned away by, among other countries, Canada. The boat and its fate are not described by the narrator, but this was the SS St Louis, a luxury liner bound from Hamburg to Havana carrying Jewish children and families fleeing the Nazis; its story is a footnote, albeit a shameful one, in Canada’s history, but Windley reminds us of this moment in history and its consequences by inserting a quiet reference to that boat in her story about the Holocaust.

By the time we reach part three and are fully engulfed by the horrors of the war, two characters have captured our full attention: Anna, the daughter of Dr. Magdalena Schaefferová, and Natalia, the wife of journalist Count Miklos Andorján and daughter-in-law of the Dowager Countess Rozalia. Through these two women, the multi-generational trauma of the war is both experienced and witnessed. Anna will survive the camps and live to keep the memory of what happened alive; Natalia will also survive to be reunited with her husband, who nearly died, and with her beloved mother-in-law, to whom she returns in Hungary. After their reunion, the Dowager Countess tells Natalia, “everything comes together [. . .] when you have a little faith in life” (p. 322). And so it is: these women’s life-stories intersect as they move from Prague to Berlin to the estate in Hungary and then to safety, but I will say nothing more lest I give the plot away.

The central message of this novel is, I believe, that we must actively remember each other and our past histories, never more so than during devastating events like the Second World War. We must remember and bear witness to those who died, who suffered and, therefore, cannot speak for themselves across history to our present. We must also remember those who perpetrated atrocity, who silenced millions. Anna’s mother, Dr. Magdalena Schaefferová, advises and warns her young daughter about the ethical position to embrace in the future and that the trauma of their time and place will persist. “It’s up to us to help each other,” she says: “You can pray for us, Anna, and for the victims of brutality. But for murderers you don’t have to pray. They don’t deserve forgiveness. [. . .] We can’t pretend life will ever be the same. The scars might fade but will never go away. For this, you must prepare yourself” (pp. 232-33). Anna will remember these wise words and carry them with her as she prepares to begin a new life that is filled with hope and grounded by memory. And Midnight Train to Prague will help readers remember what happened so many years ago and how memory can help us all survive to live with hope.

*

Sherrill Grace, OC, FRSC is a UBC Killam University Professor Emerita. She has published extensively on Canadian literature and culture and is the author of several books including Landscapes of War and Memory (2014) and Tiff: A Life of Timothy Findley (2020). Editor’s note: see here for Sheldon Goldfarb’s review of Sherrill Grace’s Tiff in The Ormsby Review 921 (September 22, 2020).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#941 Remembering World War Two”

Thank you so much for this wonderful review!