#937 Radishes and Gooseberries

Masters and Servants: The Hudson’s Bay Company and its North American Workforce, 1668-1786

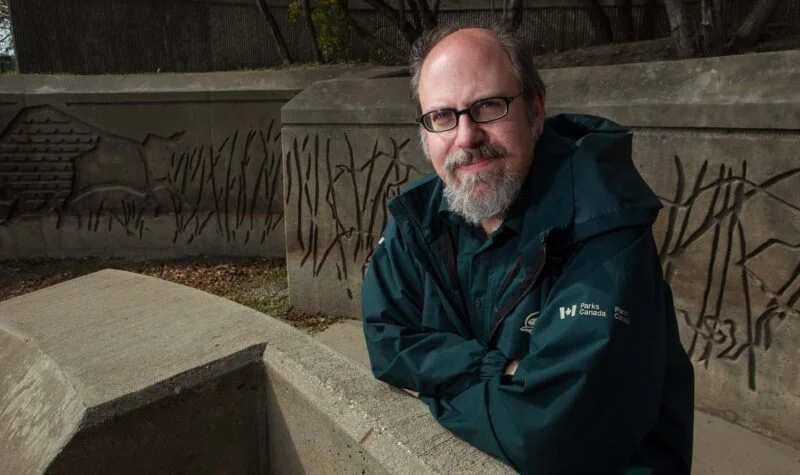

by Scott P. Stephen

Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2019

$44.99 / 9781772123371

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Radishes and Gooseberries: Meet some of the people who are missing from your high school history textbook…

Radishes and Gooseberries: Meet some of the people who are missing from your high school history textbook…

“Radishes and Gooseberries!” Our high school social studies teacher would drill the names into us so we would better remember them for next week’s quiz. Who were they and who were the countless nameless “servants” hired to unlock the abundant wealth of Canada’s Northwest Territory for the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), the famed Company of Adventurers? A new book offers some complex answers.

Parks Canada historian Scott Stephen reminds us that Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart des Groseilliers, my teacher’s radishes and gooseberries, were among the earliest fur traders working for the Company during its humble first decade after 1670. That was the year the British government granted a royal charter licensing it to plunder the vast Canadian northwest.

We are also introduced to other notable Company men — Henry Kelsey, David Thompson, Anthony Henday — all names my teacher cited but without a handy memory boost. Scouring the many sources, Stephen provides the details of their stories. But there were also the lesser-known Company men, the ones that could easily have been left out of the textbooks.

Blacksmiths, bookkeepers, loggers, tanners, coopers, cooks, sail-makers, interpreters, surveyors, clergy, the list goes on as Stephen marches us through the lives of the early Hudson’s Bay worker. Some were unscrupulous fortune hunters. Some chose to abandon families in England and travel thousands of miles to seek their livelihood in furs.

We learn how they lived, what and how they ate, how much they were paid, how they were hired in London, mostly, but also en route to the New World via the Orkney Islands.

What kind of people were they? Were they educated? Were they married? What was their status in the class-conscious homeland?

We also read stories of belligerence, arson, thievery, and murder. Stories of greed, cheating, and stealing documented as well as issues around alcohol consumption. “Drink played an important role,” Stephen notes, and its “strategic use . . .encouraged workplace conviviality, harmony and fellowship.” It also created much havoc for both HBC workers and First Nations people.

Sex was another issue. In their “pseudo bachelorhood” state, men took First Nations wives only to abandon them once their tour of duty was completed. The London committee overseeing the Company frowned on any hint of a long-term relationship because it threatened to disrupt the economic balance the committee wanted maintained.

The hierarchy of government at an HBC factory, with its fort and surrounding community of service providers, is outlined in detail, starting with the functioning of the “household.” This was the “central social institution” where “Early modern elites often sought to supplement political and economic authority with cultural authority [that] encouraged hierarchy and subordination.” (“Early modern” is Stephen’s substitute for “pre-industrial.”)

Households were extended beyond family members to include apprentices and servants, and Stephen enlightens us about everyday life in such a “household economy.” He also details the various activities that are needed to run an HBC factory, the name used to describe a Company “trading establishment.”

Curiously, there is little in the book to suggest a rebellious workforce. No sign of union organizing efforts, but perhaps this is understandable. These were far-flung workplaces and workers were spread over a vast territory with little chance of organizing a communications network. In addition, workers came and went. To organize them would have been tantamount to organizing McDonald’s workers today.

There were complaints, of course, grievances about wages and working conditions, but the Company had an all-powerful grip on the men it counted on to keep the riches flowing from the wilderness. The HBC worker might also refrain from complaining too vociferously in hopes that a credential from the Company would get him a job when he returned home.

Still, Stephen takes us deeper into the underbrush uncovered by journalist Peter C. Newman in his magisterial popular history of the Company. Two key differences. First, Newman was writing about the company as a business whereas Stephen is observing the archival data that define it as a workplace. Second, Newman was not hogtied by the rigours of academic style.

This book is based on a dissertation and is not written in a popular style. It is not meant to tell a story so much as to support an argument. While Stephen has done his homework and clearly knows his subject, he makes no attempt to embellish. Everything is thoroughly documented using the Company’s voluminous archive. The journals and correspondence of Company men and the published works of early company historians are thoroughly mined.

Stephen is meticulous in his use of quotations in the vernacular of the day. He argues that “language used in the HBC’s early records provides significant insight into the perceptions and understandings behind the words.” Probably so, but it requires some reader patience to fully appreciate the point.

The book contains several images, but these are often early maps and fort designs. For a more exciting visual sense of what life must have been like for HBC workers, try the novel by Albertan Fred Stenson, The Trade (Douglas & McIntyre, 2000), or Barkskins, the National Geographic television series based on the novel by American writer Annie Proulx.

It is probably a romanticized image — the HBC man is a handsome devil with a rakish wide-brimmed hat and musket pistols at the ready. But Proulx’s rough-hewn village and surrounding Iroquois territory offer a glimpse of what life might have been like for Stephen’s masters and servants. You might even get a glimpse of radishes and gooseberries.

*

Ron Verzuh is a Canadian writer, historian, and documentary filmmaker presently based in Oregon. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh’s most recent contributions to The Ormsby Review are of books by Christine Hayvice, Keith Powell, Tony McAleer, Norm Boucher, Ron Shearer, and the Graphic History Collective.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#937 Radishes and Gooseberries”