#921 The death and life of Tiff Findley

Tiff: A Life of Timothy Findley

by Sherrill Grace

Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2020

$39.99 / 9781771124539

Reviewed by Sheldon Goldfarb

*

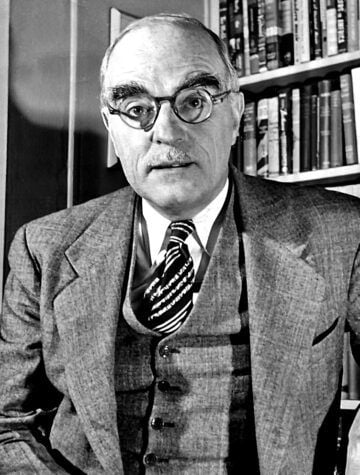

In 1993, towards the end of his life, the noted author Timothy Findley gave a talk at Duthie’s bookstore in Vancouver on one of his favourite topics: censorship. Only this time he broadened his focus from his usual criticism of right-wing book banners to include the new forces of political correctness on the Left, who were beginning their campaign against authors who were “too Eurocentric,” especially authors who were Dead White Males.

In 1993, towards the end of his life, the noted author Timothy Findley gave a talk at Duthie’s bookstore in Vancouver on one of his favourite topics: censorship. Only this time he broadened his focus from his usual criticism of right-wing book banners to include the new forces of political correctness on the Left, who were beginning their campaign against authors who were “too Eurocentric,” especially authors who were Dead White Males.

Said Findley: “I shall be just another dead white male in 20 years or so. And a gay one! Eurocentric! Middle class! God! What could be worse?”

Strange this conflation of prejudices old and new (gay and dead white male); Findley perhaps suffers from the latter now: I could see no sign of him in the UBC English Department course descriptions, though an adaptation of The Wars, his Governor General’s Award winning novel from 1977, did appear on stage at the Freddy Wood Theatre at UBC just last November, and you can still find him in course descriptions at the U of T. Still, maybe he is just too Eurocentric for our times, focused largely on tales of the World Wars in Europe, not to mention his stories about upper middle class Rosedale in Toronto, an area he grew up in (and to call himself middle class was a bit of an understatement since his grandfathers were members of the Toronto business elite, one of them being the president of Massey Harris, though it’s true the family’s fortunes had declined by Findley’s time).

One can find all this out in the excellent biography of Findley written by Sherrill Grace, emeritus professor in the UBC English Department, but mostly you will find that the main prejudice affecting Findley stemmed from his sexual orientation. It was not acceptable, or even legal, to be gay in Ontario in Findley’s time, and he had to engage in furtiveness and pretence, pretending even to himself, which is what must have motivated his brief and disastrous marriage to the actress Janet Reid.

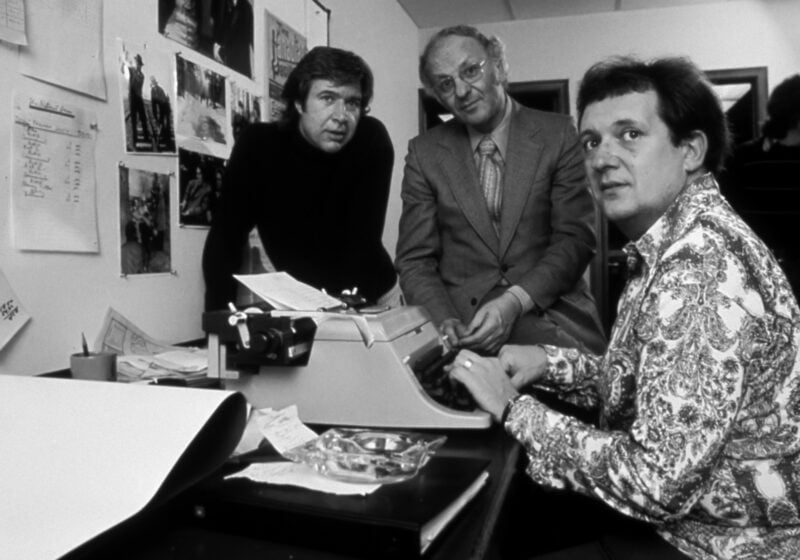

Findley himself started out as an actor, appearing at the new Stratford festival in Ontario in its first year (1953), and getting roles like Osric in Hamlet, but he eventually decided that his true talents lay in writing, and the best part of Grace’s book is the depiction of the years when he discovered his true calling. Along the way he benefited from the mentoring of Alec Guinness (though he had to put up with the famous actor’s sexual propositions as well). Guinness encouraged him to focus on writing, as did the American novelist Thornton Wilder, and it is fascinating to follow Findley as he makes his way from being a struggling actor to becoming a successful writer.

Grace is helped in tracing this development by the extensive journals Findley left behind. First piece of advice to any would-be biographer: Find a subject who’s left behind lots of material to work on. When there’s no material, Grace herself runs into difficulty, for instance in sketching Findley’s childhood, which she jumps to tell us was not that unhappy despite what Findley later said about it. For the later years when she has more material Grace does not resort to such pre-emptive declarations; she lets the material speak for itself, and so we see the angst of the 24-year-old Findley, who analyzes everything he does, often gives way to despair (though he keeps warning himself not to), exuberantly thinks he will become part of the Canadian literary pantheon, then worries that he will end up a drunken wretch (he was very much prone to alcoholism).

Was he happy or unhappy in these developing years (and after)? Grace does not pronounce, but the answer is clear: He was both. He was happy to indulge in his art, producing several successful novels, but he continued to be tortured by his demons. Grace puts this down, at least in part, to the difficulties he faced because of his sexuality, but maybe genetics had something to do with it: neither his father nor his brother were gay, but they, too, succumbed to drink and despair. And then there was his schizophrenic aunt, who was also a writer. Maybe both mental illness and creativity ran in the family: are the two linked? But let’s not go there.

Grace begins the book in a strange way, with Findley’s death, and she plays with chronology throughout (though not so much in the excellent chapters on Findley finding his occupation while with Alec Guinness in London). This leads to confusion at times, and repetition, and some odd gaps: we see very well how Findley moves from the theatre to writing short stories, but then we leap ahead and he’s revising his first novel at the behest of his editor in New York. Wait, when did he write this novel? How did he connect to a New York editor?

Another effect of beginning the book with a chapter on Findley’s death is that the first chapter is not about ancestors. What a relief! I’ve often felt that biographies should begin with Chapter 2, leaving out the ancestors altogether. But in this case Chapter 2 is the chapter on ancestors. Oh, well. And then when Findley and his partner Bill Whitehead buy an Ontario farm they christen Stone Orchard, we are treated to stories about some of the previous owners and their ancestors. More ancestors! Grace says ancestors were important for Findley, and he drew on family history in some of his fiction; still, it’s more interesting to read about his developing career than to find out who such-and-such a character was based on.

And we do get an account of his career and of the themes in his works: war, violence, truth, Nature, and above all family dysfunction, especially the difficulties between fathers and sons. Findley had a difficult relationship with his own father, who was not happy to have a gay son, though he became more supportive in later years, and there was something of a reconciliation.

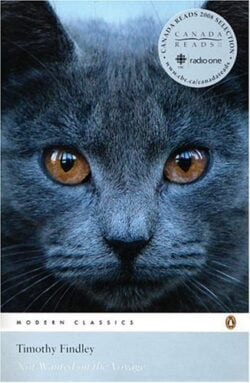

We also learn about Findley’s cat Mottle, who gets a starring role in his novel about Noah’s Ark (Not Wanted on the Voyage), and about his obsession with Ezra Pound and whether you can forgive a fascist for being a good writer. We are all monsters at times, Findley seems to suggest, but as one of his characters says: Not even monsters are monsters all the time.

Grace sometimes gets sidetracked into plot summary in the later stages of the book, and it would have been nice to end with a chapter summing up Findley’s legacy instead of an Afterword about scattering his partner’s ashes. Still, if you want to get a sense of one of the writers who dominated the CanLit scene in the latter decades of the twentieth century, this is the book for you.

*

Sheldon Goldfarb is the author of The Hundred-Year Trek: A History of Student Life at UBC (Heritage House, 2017). He has been the archivist for the UBC student society (the AMS) for more than twenty years and has also written a murder mystery and two academic books on the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. His murder mystery, Remember, Remember (Bristol: UKA Press), was nominated for an Arthur Ellis crime writing award in 2005. His latest book is Sherlockian Musings: Thoughts on the Sherlock Holmes Stories (London: MX Publishing, 2019). Originally from Montreal, he has a history degree from McGill University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba, and two degrees from the University of British Columbia: a PhD in English and a master’s degree in archival studies. Editor’s note: Sheldon Goldfarb has reviewed a dozen books for The Ormsby Review, the most recent of which are by Philip Resnick, Miriam Nichols, Keith Maillard, Edwin Wong, Rod Macleod, Janet Nicol, and Howard White & Emma Skagen (editors).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#921 The death and life of Tiff Findley”