#900 Teaching the Cariboo way

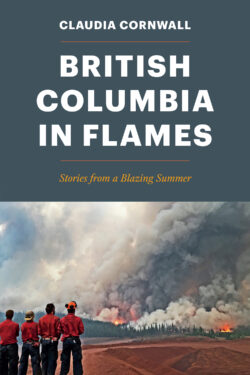

British Columbia in Flames: Stories from a Blazing Summer

by Claudia Cornwall

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2020

$26.95 / 9781550178944

Reviewed by John Gellard

*

“When a fire is roaring through the crowns of trees and flames are shooting up for fifty metres, the intensity can hit 150,000 kilowatts per metre. In one hour a metre of fire releases enough energy to power fifteen homes for a year.”

“When a fire is roaring through the crowns of trees and flames are shooting up for fifty metres, the intensity can hit 150,000 kilowatts per metre. In one hour a metre of fire releases enough energy to power fifteen homes for a year.”

And when the fire front several kilometres wide is advancing faster than a man can run, generating enough wind to throw lampshade sized embers a kilometre or two, the last place you want to be is in its way, especially if the fire-born updraft is creating high pyrocumulus clouds which blast lightning bolts to the forest below. It’s a wonder there were no human deaths in the wildfires of 2017, the record year for BC wildfires, only to be exceeded by 2018 for area burned and property destroyed.

Claudia Cornwall has written a most compelling and detailed compendium of stories about the heroic people who battled, escaped, and resisted the firestorms that ravaged British Columbia’s central interior in the summer of 2017. The stories come out of more than fifty hours of interviews, and there’s a deep personal interest in a family property on Sheridan Lake.

The Cariboo region in BC’s central interior is an intermontane patchwork of forests, rangeland, large ranches and lakes stretching along the Fraser from roughly Lillooet to Prince George, and west into the Chilcotin. Its main artery is Highway 97, the old Cariboo Road to the goldfields of Barkerville. Communities along the way are named after miles from Lillooet, for example 100 Mile House.

The 2017 summer was exceptionally hot and dry. The lightning strikes began on July 7. Within a day, 182 fires were burning in BC, and you never knew where the next one would begin. The fires grew explosively, and you had to be prepared to evacuate on short notice. The Gustafsen Lake fire west of 100 Mile House grew eventually to 5,700 hectares. The Elephant Hill fire near Cache Creek grew to 192,00 hectares by late August. Thousands of people were affected. If you live in the Cariboo, you are certain to know several people whose stories of superhuman efforts to save their homes, their families and their animals, and to help each other are detailed in the book.

*

Well, how do you deal with an onslaught of out-of-control fire dragons? Let’s have a brief look at some of the methods which brought order out of chaos, and let’s get to know a few names.

The BC Wildfire Parattack unit is “an elite group of firefighters known as ‘smokejumpers.’” Their job is to fly fully equipped in a chopper or a Twin Otter to a small fire, parachute in, and put the fire out. They must be ready to go anywhere and change plans on very short notice — “fluid” rather than flexible. Max Forester tells of saving a little community of houses from the Dragon Mountain fire near Quesnel. Funny outcome: a couple of white llamas came out of the forest stained red.

Blame the water bombers dropping water and red fire retardant. Specially designed CL 14 “Superscoopers” can lift 6,000 litres per drop, and the “Fireboss” planes can drop 3,000 litres of red retardant.

Brad Potter was keen on protecting his “Wind and the Pillows” resort on Green Lake. The Elephant Hill fire was bearing down on him, so he was happy to see the bombers. Brad had prepared his place by clearing his hay field and putting out sprinklers pumps and hoses to extinguish any flying embers that might land on the house. Then the Structural Fire Protection crew appeared. “Five guys…. They hop out and climb all over my building. They put sprinklers on the four peaks of the house, two on my shop, one on every building, and hooked them up to my fire hoses and pumps. They supplied sprinklers.” Wind and the Pillows was saved.

Evacuations must have been a nightmare, mitigated by the thorough organization of the BC Wildfire Service and RCMP, and the generous spirit of people who helped others with transportation of horses and dogs. Staff Sergeant Svend Nielsen presided over the evacuation of the 100 Mile House area. People, horses and vehicles crammed into the Williams Lake Stampede grounds. Then, Williams Lake was evacuated, and thousands came south and invaded 100 Mile House.

RCMP officers had to check evacuated areas to make sure people evacuated. You had the option of staying to protect your property. You’d be asked, “What is the name of your dentist?” Guess why.

Some exemplary individuals should be mentioned. Follow the story of Heather Gorrell of Lac la Hache as she performs a hair-raising night time rescue of a stranger’s horses, and then has to rush home to her own animals.

Did you know that we almost lost Williams Lake? Evacuated, the town was threatened by a fire that came dangerously close to a huge pile of 66,000 logs at three sawmills northwest of the city. The burning logs would have thrown embers far and wide and the city could not have been saved. Samantha Smollen, a young, energetic forestry student and the Alkali Unit Crew did ground work to protect the logs. They saved Williams Lake.

There were several store keepers and gas station owners who made huge efforts to provide food and supplies to itinerant evacuees. Jin Woo Kim of Clinton was one. Pam and Kam Jim had a store in Little Fort (pop 350). “We made the decision to stay open 24 hours because there were five thousand people coming down [from Williams Lake].”

Meet Ryan Lake, 70, on crutches with arthritis in his one leg. He’s a comedic raconteur. He decided to stay and protect his A-frame cabin near Clinton as the Elephant Hill fire advanced. “They asked me who my dentist was.” He was helped by “the two gals from next door,” Morgan and Kim Bosche. The Structural Protection crew “swept over us like a swarm of locusts” and the choppers lit backfires. His pump kept air locking and his well kept drying up “as the elephant came charging down the hill at us.” Do they win the race? Read and find out. Ryan’s story is worth the price of the book.

The fires reached the Bowron Lakes Park. Canoers Andrea and Rick Holzapfel and their boys, Tom and Jack, 5 and 3, had to get out quickly. Read about their escape as they bushwhacked through portages and battled “six-foot waves breaking over the top of our canoe.”

You’ll find surprises in dozens of the stories. Nowhere else will you find this much real life drama between two covers. Read the book and prepare to be overwhelmed.

*

What are the lasting effects of the 2017 firestorms? 300 houses and structures were lost. 1.2 million hectares of land were burned over. The forests might take a generation to recover, and much of the rangeland will not be productive again for a couple of years.

There is an increased danger of spring flooding. Without the forest cover to hold rainfall and slow down the snowmelt, the runoff will be much faster. As well, the burned-over soil is often “hydrophobic” — so dried that the rain doesn’t sink in but just runs off into the creeks that overflow and flood the land.

Then by the following summer, the remaining forests are dried out again, waiting for lightning strikes to set off the firestorms. The 2018 fires broke the 2017 record, with 1.35 million hectares burned in BC.

What can be done to avoid future disasters? The book’s final chapter, “Let us Conspire with the Forests” gives some convincing answers. The author looks at the example of Sweden, which increases its standing timber while it cuts more wood than we do in BC.

First, we could easily remove excess fuel from the forest floor, leaving enough deadfall for wildlife habitat. Loggers could remove their waste wood and make biomass fuel.

We could replant logged areas with a mixture of conifers and deciduous trees. Our present practice of putting in single species lodgepole pine plantations is asking for fire, especially when the pine beetle kills the trees. Deciduous trees fertilize the soil. Aspens are fire resistant and they increase the carbon capture of the forest.

We could use “controlled burns” to provide a barrier to fires. The old First Nations’ practice was to burn up to the snow line in the spring. They created a patchwork of forest and open meadow which encouraged beneficial plants and game.

Old growth forests are the best carbon sink of all, so we could reduce global warning by not cutting them down. Jens Wieting, Sierra Club campaigner, says, “We cannot save the climate without saving the forest, and we cannot save the forests without saving the climate.”

We can and must reduce the wildfires. Note that the 2017 wildfires “pumped out a record breaking 177 million tons of CO2.”

Indeed, let us “breathe together with the forests. Let us preserve and protect them for our mutual benefit.”

British Columbia in Flames is a magnificent book. It describes the nature of forest fires and explains how fires are managed. The larger purpose of the book is to celebrate the heroism and resourcefulness of the hundreds of people whose stories are included – people who made huge sacrifices to meet the challenges and to help each other. The book will no doubt be a cherished heirloom for everyone involved. “They accepted what life handed them and didn’t ask for special favours, even when the going got rough. It’s the Cariboo way.”

*

John Gellard spent his childhood in England and Trinidad, donated his adolescence to an English boarding school, earned an MA in Philosophy from the University of Western Ontario, and taught English and Drama in London, Ontario, for seven years. In 1973, he arrived in the West Kootenay where he felled and peeled pine logs on his “wild land” property and built a log cabin. Gravitating to the city, he taught for thirty years at Vancouver Technical Secondary School and Kitsilano Secondary. He still helps run writing workshops for students, notably (since 1993) an annual overnight retreat on Gambier Island. His articles have appeared in the Globe and Mail and Watershed Sentinel. He takes an active interest in environmental issues and travels extensively in B.C. He lives among friends in Kitsilano and on Hornby Island, has two grown sons, and retired from teaching English and Writing at Kitsilano Secondary School after being named Canada’s “Best High School Teacher” in a Maclean’s poll in August 2005. Editor’s note: John’s recent reviews for The Ormsby Review include books by Dimitri Bayanov, John Zada, Frank Wolf, Wendy Holm, Sarah Cox, and Eileen Pearkes.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster