#896 A Mennonite father and son

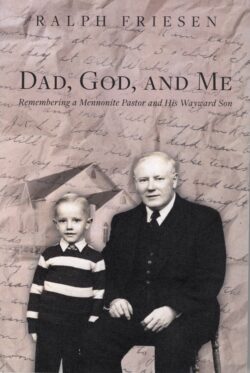

Dad, God, & Me: Remembering a Mennonite Pastor and His Wayward Son

by Ralph Friesen

Victoria: FriesenPress, 2019

$20.49 / 9781525560880

Reviewed by Randy Janzen

*

After reading Ralph Friesen’s Dad, God and Me, I was struck by the common human urge to understand the past and reconcile ourselves with long-ago events. It is no wonder that history is such an important discipline; and Friesen, an accomplished historian, invites us via this book into his very personal relationship with his father, his distinctive Mennonite heritage, and his intimate struggle with understanding God. That is not to say the story is insular; on the contrary, Friesen retells a poignant story that has universal appeal.

After reading Ralph Friesen’s Dad, God and Me, I was struck by the common human urge to understand the past and reconcile ourselves with long-ago events. It is no wonder that history is such an important discipline; and Friesen, an accomplished historian, invites us via this book into his very personal relationship with his father, his distinctive Mennonite heritage, and his intimate struggle with understanding God. That is not to say the story is insular; on the contrary, Friesen retells a poignant story that has universal appeal.

Friesen offers a historical account of his Mennonite pastor father, Reverend Peter D. Friesen, who played an important role in the history of the town of Steinbach, Manitoba, where he navigated his conservative congregation through decades of turmoil, assumed the role of visionary and mediator, and offered such endless behind-the-scene support that sometimes he didn’t seem to have much time left for his own family. The touching retelling of his father’s life goes beyond the man, however, and delves into the backdrop of Mennonite history, culture, and life in general, and specifically into the Kleine Gemeinde (“little church” — a conservative Mennonite sect whose members were among the first European settlers in Manitoba). This background milieu provides the context for Friesen’s search for a connection with his father, who was prematurely taken away from him after suffering a debilitating stroke.

Dad, God and Me is about unfinished business, relationships interrupted by illness and death — relationships complicated by cultural norms that paradoxically bring loved ones together while also setting them apart. By the end of the book we are left not so much with a resolution as a coming to terms with the tensions, paradoxes, and mysteries of complex family relationships that span generations and traverse changing cultural and generational norms of this ordinary Mennonite family on the Canadian prairies. This well-written story can make an ordinary life seem extraordinary, while at the same time compel us to empathize with seemingly preposterous cultural practices of a conservative Mennonite sect (especially when viewed through a modern lens). It is a story of reconciling incongruities — the sometimes harsh and dogmatic rules of morality juxtaposed against unwavering community solidarity and mutual support; the family relationships characterized by formality and distance juxtaposed with unshakable commitment and quiet nurturing.

For those interested in Mennonite History, Dad, God and Me provides a personal account of living through a significant cultural transition of Russian Mennonite life in Canada, where religious practices, language, and everyday cultural norms became increasingly out of touch with those of the dominant Canadian society. But the book will appeal to an audience larger than just those interested in Mennonite History. Friesen’s book is not exclusively inward-looking — the story is a universal one written for a general audience where the reader understands the intergenerational struggles between those hanging on to the old country and those who are pushing the boundaries to embrace modern Canadian life, layered with the tensions between traditional religiosity and modern secularism. This process could be described as a universal passage by any immigrant community, whose journey from old ways to news ways is marked by challenging family dynamics, unfulfilled expectations, letting go, and an ultimate and unique assimilation passage by the younger generation who ultimately adopt the modern ways of the Canadian dominant society.

One theme that Friesen explores throughout the book is the relationship between religion and family, and how religion impacted what Friesen tried to decipher as a normal father-son relationship. God, it seems, sometimes gets in the way, with interesting and unpredictable consequences. As Friesen recounts the coming of age stories of himself and his siblings, he comes to realize that to reject religion is also to reject his father. The broader cultural milieu inextricably links the love and connection of his pastor father with the embracing of organized religion. The journey to accept one left little room to disavow the other.

The relationships between Dad, God and the author are complicated. For example, Friesen struggles with the two sides of his father: he nurtures the physical and spiritual needs of his large congregation, but he is almost inattentive to his son and farms out the role of saving his soul (which ostensibly was the most important job of a father) to others – to visiting evangelists, camp counsellors, and aggressive ministerial persons who corner the young Friesen in sometimes comical and even frightening interactions. The disconnect is felt in a number of ways. Ralph Friesen and his father are able to salvage something, even if he never embraces the salvation that his father so wants. However, there is an undertone of hurt – why did my father spend so much time working on the spiritual well being of the entire community, but not my own?

In this biography of Peter Friesen, his son manages to tuck in a number of stories about himself in ways that enrich the book with the coming of age turbulence of a boy at odds with his father and with God. It is hard to untangle all three. In one memory, Friesen shares a time when his father gave him the strap. He muses on the incongruity of the use of corporal punishment as an invitation to experience God’s love and forgiveness. After the strap there is the ensuing prayer, a call not only for forgiveness but also for being called back into the fold for reconciliation, and a childhood misdemeanour is a crisis with the ability to bring Dad, God, and Ralph back together.

What happens when all these narratives are interrupted by a profound health crisis? When Friesen’s overworked father has a life-altering stroke, everything changes. Rev. Friesen becomes paralyzed on one side and confined to a wheelchair, with his speech and cognitive functioning compromised. Ralph Friesen’s ongoing quest for father-son bonding is now forced down an unforeseen and unfamiliar path. He is now placed in the strange and new role of caregiver for his ailing father, a role for which his father’s distant and formal demeanour did not prepare him. His longing for physical affection and basic touch from his father only gets fulfilled through their awkward reversal of roles as he helps his father with personal care in a way that Friesen describes as uncomfortable and unsatisfying.

The book’s narrative continues long after Friesen’s father has passed away. He recounts how his adult life, marriage, and his own parenting seem to be made intricately complex by his unresolved relationship with his father. In fact, the book itself may be Friesen’s best way to achieve the longing connection with his father, even if he is already gone. As Friesen writes, “I have refused to release him until I receive a blessing.” That blessing might now come from those who read this book, who will no doubt connect with the author by his sharing a truly human story of familial love.

Compelling, searching, and revealing, Dad, God, & Me: Remembering a Mennonite Pastor and His Wayward Son can offer us all a story of hope and connection to help us navigate our own unfinished and unreconciled relationships with our parents, our communities, and our history.

*

Born in 1964, Randy Janzen was raised in Steinbach, Manitoba. He completed a BA in Sociology (1989), a BN (1990), and subsequently worked as an outpost nurse for a number of years in isolated communities in Canada’s north. He then earned an MSc in epidemiology and moved into teaching at the post-secondary level at Selkirk College. In 2007 he completed a year of graduate course work in Peace Studies, and then moved into the Taos Institute where he completed his PhD dissertation. In 2010, he was appointed Chair of the Mir Centre for Peace at Selkirk College, where he taught undergraduate courses in Peace Studies, managed the peace centre, and developed community education and service projects. He has also worked in Guatemala (1993 and 2007-8) and in Kosovo (2011). Randy and his wife Mary Ann live in Nelson.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster