#876 Stainsby’s carbons and files

MEMOIR: Writing My Father

by Meg Stainsby

*

After twenty years of carting it around unopened, I unpacked a stale cardboard box stuffed with crackly, yellowed sheets of typescript — some still clinging to their carbons, all faint and fusty — and began a solitary trek across a forty-year expanse of written terrain that my father had left scrawled out behind him. Donald Orval Stainsby, born New Year’s Day, 1928, in Fernie, BC, spent his life writing. Upon his death, in 1981, I took custody of this box of manuscripts and files; finally, I decided it was time to open it.

I was accepting an invitation from a dead man.

As I marked my own trail through my father’s words, my trek became both a literary exercise and a personal pilgrimage. I haven’t always respected my father as a parent, but I had many reasons for rescuing this box of manuscripts from the obscurity of my attic: because I felt the burden of being its sole guardian; because I wanted to mark the twentieth anniversary of the man’s death; because I wanted to learn what I could of Don Stainsby as writer and adult in the world; and, perhaps most compellingly, because I wanted to write, my own creative drive pushing me to reconcile myself to whatever legacy my writer-father might have left me.

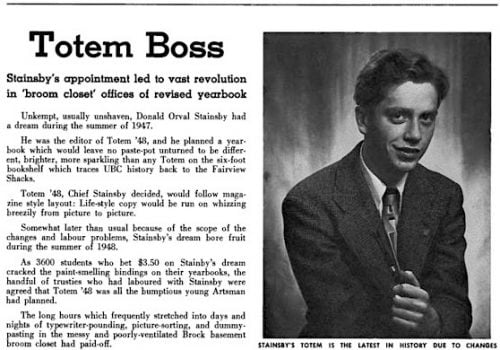

Although anxious to dive into my father’s fiction, I was moved by what I witnessed initially about his earlier efforts, as editor of UBC’s student paper, The Ubyssey, in the late 1940s, then as a newspaperman in Vancouver in the early fifties. A scrapbook, tossed into the box along with all the writing — the early captions written in my grandmother’s tiny, steady hand, later ones dashed off in my father’s own hasty script — preserved evidence of my father’s relationships with local literary personalities of his day. His newspaper columns, such as “Books and Bookmen” in The Vancouver Sun, and his live interviews with authors, on both local CBC and CHQM radio stations, brought him many of these connections.

I knew a little about these friendships before reading his old notes and letters; what I had not appreciated was the esteem in which other writers held him. Ethel Wilson, the notoriously aloof elder stateswoman of letters, singled out my father as a reviewer she trusted and respected; among my father’s papers are two hand-written letters from Wilson, thanking him for his intelligent comments about her fiction.

Letters crossing both ways between my father and Margaret Laurence are warmer, more familiar. Laurence asks after my mother, about my recovery from a car accident I apparently suffered as an infant. She and my father swap writerly details and excitement over evolving projects. In one letter, Laurence confesses relief that my father liked a first-draft of The Stone Angel she’d sent him, particularly grateful that he was convinced by the soon-to-be-classic character Hagar. Poet Earle Birney makes cryptic remarks in a letter about the “real gossip” he can’t commit to paper, then invites my father to his West End flat for drinks and conspiratorial fun. Writers liked my father.

Emboldened by what I found in these letters, I took a couple of risks I hadn’t planned on — side-trips of sorts. Family lore had long cast Alice Munro not only as another writerly friend of my father’s but possibly as his lover: she was also reputed to have drawn upon him as inspiration for the short-story character Hugo (from “Material”) in the early 1970s. Hugo, like my father was, is a man from a mining and forestry town, a man whose father died of a heart attack, a man with notoriously bad teeth — Dad’s had been replaced by full dentures before he was thirty — and, most tellingly when Alice knew him, a man of many wives and twice as many children.

My father and his first wife Mari had met Alice and Jim Munro in the 1950s and become fast friends, later living as neighbours on Ottawa Road in West Vancouver. Yet the files of my father’s correspondence yielded no trace of this friendship. In the spirit of my quest, I wrote to Munro, asking for memories of my father and their long ago friendship. My letter went east as Munro wintered out west, but when the letter found her, she telephoned me. She was gracious, generous with her time as she recalled my father and his writing. She alluded obliquely (I think) to rumours of their romantic ties, hoping (again, I think) to put them quietly aside. She was emphatic about not having modelled the character Hugo, himself a writer, after my father: she said she would not have done so because she “did not see [Don] as disconnected from all other realities but his own, as Hugo is.” I bit my lip and stayed silent here.

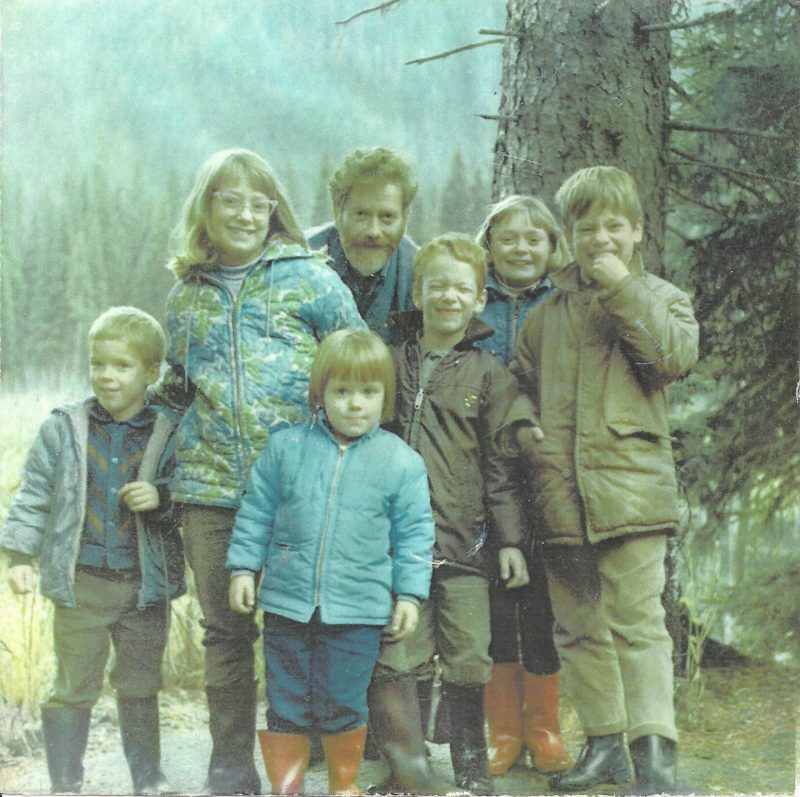

But I did go on to answer Munro’s questions about my father’s later life, after their close years — telling her, for example, about his time in the early seventies driving around Europe. Her enthusiasm was immediate: “Oh, wonderful! Was that good for him, as a writer, do you think?” Imagine my surprise. I found myself agreeing that of course it might have been wonderful for him, but I’d been more inclined to focus on what he left behind: six children, two crazy ex-wives and no money. “Oh,” Munro said, “your mother must have felt so abandoned by him.”

Indeed, I thought.

What was clear to me as Munro spoke was her affection for my father, her admiration for him as a writer, and her sense that his choices as an artist might have been viable, even enviable ones. As we were about to ring off, Munro remarked, “You look just like your father, you know — I suppose you get that all the time?” Imagine my surprise. We were speaking by phone. I found myself scanning my bedroom for a hidden camera. I must have sounded flustered because she reminded me of our brief meeting at one of her book signings in Vancouver in the mid-1990s, saying she had noted my resemblance to my father then.

“No,” I replied, “no one has ever said that.”

My mother always insisted that I took after the Gibsons, her father’s family, and did not look like a Stainsby at all.

“Oh,” Munro went on, “I knew right away you were Don’s child.”

We said goodbye. I later sent her six of my father’s best stories by way of a thank you, and we spoke again briefly about his fiction; but in that one quick aside, Munro had already contributed to my pilgrimage a boon I hadn’t known to ask for.

With such encouragement, I next sent an email to writer/editor Robert Fulford, with whom my father corresponded a good deal in the sixties and early seventies. In another generous reply, Fulford, like Munro, handed me a gift in the form of a memory: he related a brief tale of my father, a mea culpa story in which my father’s climactic line was “I did a bad thing.” Imagine my surprise again: this phrase, verbatim, appears in an anecdote I had recently sketched, a brief tale, set when I was four, in which I seek out my father to confess that I have stolen some coins from a friend’s piggy bank. I announce my crime in just this way: “I did a bad thing.” Amused by the uncanny echo, I sent Fulford my anecdote; in his reply, he noted the mirror phrasing as an example of how families often develop and speak their own “private languages.”

Fulford’s comment, like Munro’s, made me temporarily re-frame my travels, directing me to turn inward. Two CanLit figures who “knew Don Stainsby when…” gave me a way to acknowledge a little piece of my father within myself — in my use of words, the turn of my nose, perhaps, whatever others see that I do not see in myself. That I carry any echo of this man within me was a possibility I’d not been prepared to consider before. To be drawn to dwell upon this now, seriously, was a complex and loaded gift. And even if ultimately the likeness between my father and me is slight, or the comparisons prove more disturbing than pleasing, I concede that my life mirrors his enough that I may learn something about examining what it means to be “Don’s child.”

Once immersed in my father’s short stories, I found myself pausing often to think about the relationship between his writing and what I know of his life, the “real world” through which he daily moved. Or more precisely, about the considerable lack of relationship between his actions as father and his preferred identity as writer. Sure, I had undertaken my pilgrimage in a spirit of reconciliation. But how to reconcile, for instance, Munro’s delight that an artist should wander Europe, soaking up life and storing experiences against later creative need, with my own child’s view of my father as having run away from home and family to live a remarkably selfish life?

Early along in my reading, I was very nearly warned off my conciliatory path by an encounter with one of my sisters. We were in sporadic touch at the time, but I sought her out the very day I posted my letter to Munro. After an hour’s chat, as we were about to part, I told her about my archival project, sketching for her a few of the themes that had captured our father’s interest over the years, commenting on how I was seeing his craft developing. As if outraged that I could compartmentalize so — as our father had done, perhaps? — my sister responded by immediately recounting one of our father’s most brutal moments, an evening when he beat one of our cats, Thursday, to death. I was five years old, my next closest brother only six, and I recall our father kneeling down to the two of us, trying to justify his savage attack on this cat, who had eaten our sister’s pet mice. As I was looking into my father’s face, I saw over his shoulder our eldest sister coming through the front door. She had gone to the garbage can where our father, assuming the cat dead, had deposited Thursday’s mangled body; sobbing, clutching the bleeding mess of fur, his eldest child looked hopefully through her tears as she said, “Daddy, she’s still alive.” In her confusion and shock, my sister could not have thought through this error, not registered that the parent to whom she was now appealing for rescue was the very man who had just violated our trust. Wordlessly, my father got up, left my brother and me with the older kids, and took Thursday back outside, where he wrung her neck before throwing her back into the trash.

Of course, one does not forget such betrayal. But to have my sibling call the image before me now, just as I was hearing some faint call to kinship with my father, felt defeating, deflating. She seemed to be declaring my reclamation project to be fundamentally ill-conceived; she seemed resistant to integrating the disparate fragments of a troubled life, to moving beyond the worst. I did not believe the same to be true of me. But I took her gesture as a challenge. As I’ve searched out more and more pieces to the puzzle that was my father, I have had to ask myself repeatedly whether in the final re-construction all fragments must be accounted for. Can they ever be? Paradoxically, are some best left outside our sense of the Whole, of the Holy? My instinct clearly is to find room in patterns — in pictures, in words — for any and every shard, but whether this is wise or ideal I cannot begin to say.

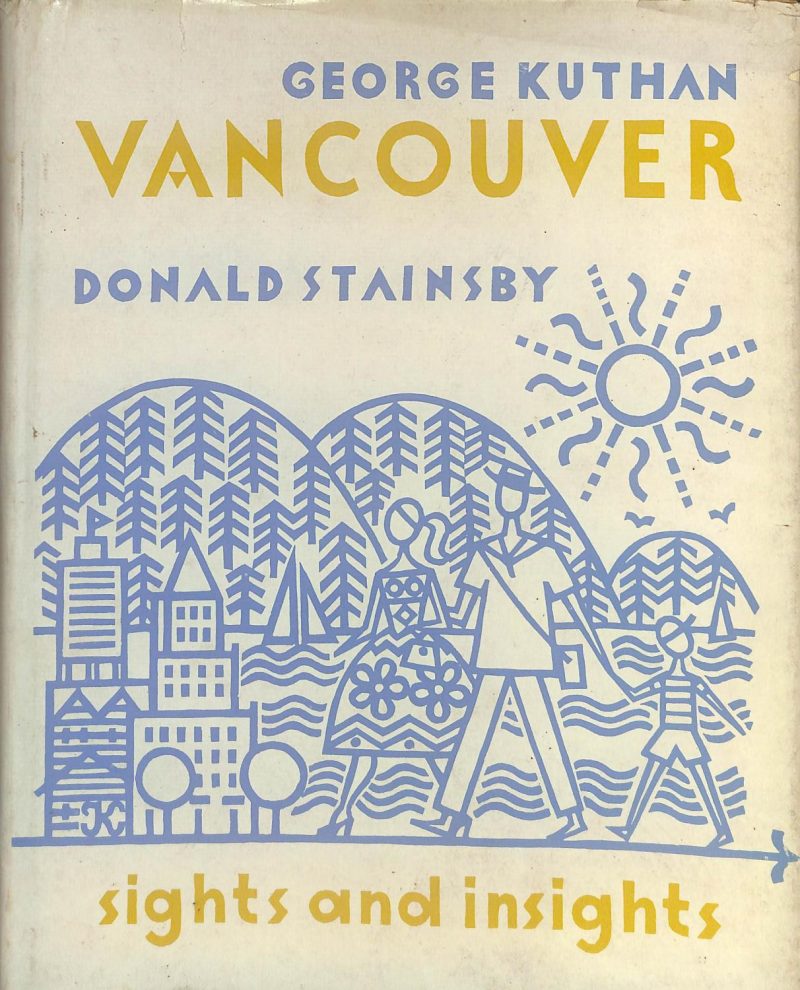

To my surprise, moving alongside my father’s writerly self drew me also to reclaim an earlier affection for him as parent. I read my way back to a simple truth: I hadn’t always disliked my dad. When I was little, I adored him, as children will, and I simply assumed that he cherished me, too. In fact, I stuck faithfully (even perversely) to this vision throughout my childhood, despite my mother’s many efforts to disabuse me of any hope that he was capable of love, of a stance towards the world other than selfishness and self-interest. I do not recall that I begrudged him sailing off with his new (third) wife for Europe when I was eight, sending in three years little support money, fewer than a half-dozen letters and once only — so far as I remember — a Christmas present. I took nothing personally in those days. I couldn’t afford to. He was, after all, a writer. At school, during “show and tell,” I would hold up his travel books and articles, beaming. My mother somehow scrounged the airfare to send one brother and me to England when I was ten. We stayed an intoxicating month. Our last evening there, my father took us to his favourite Italian restaurant: I ate Chicken Kiev, I sipped wine and liqueur, and I drank coffee, all for the first time. I was serenaded by proprietor-brothers Gino and Marco.

It was a thrill, and I felt supremely happy — until I burst into tears over dessert. My father laughingly waved off the embarrassed singing waiters, telling them I was homesick. This was true, in part. Really, the tears had come when I suddenly flashed upon what to me seemed an undeniable truth: I would never feel fully happy or whole again, ever, because while I was indeed desperately homesick for Mum, I also knew that once home, I would instantly ache for my dad. I crawled into his lap and told him this as best I could, burying my face in his rough, bearded neck. Ten years old this night, I would not see him again for a full year, by which time our estrangement was great enough that I never again sought refuge in his arms. But I seized my moment with him and cried over my trifle in Il Cervo’s Ristorante Italiano in west London; then I flew home the next day to my mother’s downtown east end Vancouver apartment in a government housing project. A few days later, I stood before Mrs. Turneau’s grade five class, reading my report: “My Month in England.” I left out the final scene.

Years later, when he was back in Canada, I continued to protect my vision of my father. When I was sixteen, my severely depressed mother demanded I declare my loyalty and “choose” between parents; when I refused, she declared the refusal a betrayal and a choice, and threw my belongings out her front door. It seems impossible to me now — and merely one more sad reflection of a child’s overriding need to believe in her parent’s love — that I did not ask or expect my father to take me in. After all, he hadn’t offered me refuge on the two earlier occasions I’d left my mother’s home. I did search him out to tell him my news, though. He was then editor of the magazine BC Outdoors, and on this day was meeting with out-of-town representatives from the publisher, Maclean-Hunter. I tracked him to one of Vancouver’s oldest, most regal restaurants. Calling him away from his business lunch, I told him I had no home, that Mum had asked me to forswear him and I’d refused. He rolled his eyes at my mother’s instability, asked that I keep him posted, then returned to his guests, leaving me in the restaurant foyer. Perhaps I had hoped for more — at least a pat on the back for not abandoning him when threatened with exile — but I do not recall taking slight at his failure to offer me some food, let alone a bed, a roof, some care. My father was not in the habit of putting himself out for others. I knew this. And I wouldn’t have asked, certainly not directly, already at sixteen being well schooled in the art of avoiding rejection. It was perhaps only by such savvy that my faith in my father was kept tucked up out of sight, safe from blunt challenge, my belief in his love never exposed for what it might have been.

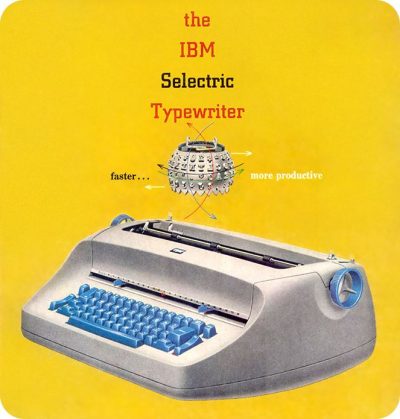

With three part-time jobs and the help of one of my sisters, I made my own way through the remaining year and a half of high school. But after graduation — when I was no longer a potential dependant, one might wryly observe — my father at last invited me “home,” to be his housekeeper and nanny to his seventh child in return for room and board while I attended university. None of us knew this for several weeks, but even as I was unpacking, my father had begun dying of lung and liver cancer. Although only fifty-three, he was typical of newspapermen of his day — a heavy drinker and heavier smoker. I had only a few weeks in which to learn the rhythm and hum of the keys of my father’s typewriter, on which he kept tapping ferociously between transfusions and bouts of chemotherapy. As long as that sound danced in the air, he could pretend all was right in his world. But the tapping soon stopped. He went quickly. On one of his final days at home, he told me that Dylan Thomas was wrong, that if one fought and raged against the dying of one’s light, one wouldn’t see the light fading. My father wanted to live his death; he wanted to experience it, not fight it. He kept pad and paper by his bed in palliative care. He scratched notes right up until the morphine won over his pain and persistence and he dropped into a coma. He died as he had lived: observing. And distant, even in the presence of his closest kin.

It was long after his death that my view of him changed. Slowly. Over the course of many conversations and several years, my then-husband began pointing out to me how appallingly forgiving all Don’s children seemed of him. Measured objectively, wasn’t my father’s performance as a parent dismal? Deserting his first wife when she was hospitalized with paranoid schizophrenia, he farmed their three children out to relatives and took up with my mother, already pregnant and soon to become his second wife. When his second marriage failed, he immediately began living with another woman; within two years, he left all six children behind in Canada and set out with this last partner for a bohemian artist’s life on the road in Europe. Rarely was he financially solvent; he contributed to his six children’s keep minimally, begrudgingly, and only at the urging of the courts. Yet he was not above calling his children to mind when convenient: although we heard little from him from Europe, his archive contains a 1972 letter to a CBC film producer, written from Denmark where my father was assembling a documentary film crew. He flippantly trots out the fact that he has six children (“somewhere”) and is sure he can lure one to Europe if the storyline requires. He was an habitual drunk and a loser of jobs. He gave us little in life and even managed to die intestate, so that his mother’s beach home on the shores of Howe Sound, to which I was brought as a newborn in 1963, and the only “estate” that might have benefited the brood, fell into the exclusive hands of our step-mother, who chose to share this legacy with only her own son. Why, my husband challenged, did we all speak lovingly of this man who had so repeatedly failed us?

Self-protection, my guess. Denial. I had spent my childhood resisting the tsunami of my mother’s anger, on the one side of me, and the equally brutal, objective truth of my father’s neglect, on the other. Only years after his death did I relax my defences and allow myself to see that, yes, okay, my father had failed me. Being a writer was no excuse; even being a great writer would have been no excuse. I began to develop what a therapist friend refers to as “righteous anger” (as most of my siblings, each at her/his own pace, has done). I raged for well over ten years, snorting dismissively at my step-mother’s suggestion that my father might have drunk as he did because of psychic, spiritual or emotional pain; that he might have sent more money to his children had my mother been more civil and generous in their interactions; that he had been, after all, an artist reaching towards personal fulfillment.

None of this washed with me. Whether the result of my own impending parenthood, or only the inevitable boon of distance and time, through my twenties and early thirties I grew increasingly critical of the choices my father made, of his selfishness, of what I came to see as his stellar failure as a parent. (Maybe this is the real reason that his papers languished unread in a torn old cardboard box at the back of my attic so long. Let’s see how he likes twenty years of neglect.)

And yet, here I was, all these years later, rifling through this stack of manuscripts. Righteous or not, anger is wearisome and demands a vigilance that doesn’t come naturally to me. So it passed, and I turned to the box in the attic. Damned if my father’s charismatic aura didn’t flutter in the air over the pages as I re-read his letters to so many editors and publishers. Damned if I couldn’t hear him again in his travel memoir, somehow insinuating into his romantic song of the nomad’s life his right — his entitlement — to the good life, to the open road of southern Italy, to cheap fresh bread and deep red wine.

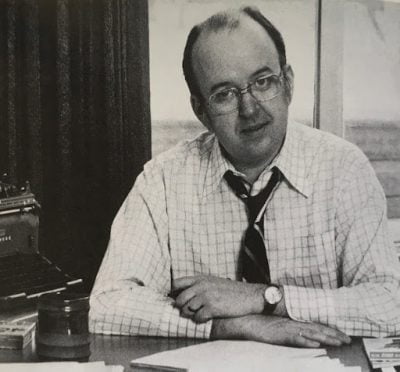

Near the end of my readerly pilgrimage, hunting for some missing manuscript pages of a novel, I found one more image of my father. Literally. Out slipped a photograph I’d never seen before, a late one, probably taken the year before his death. It’s a classic, glossy, black-and-white 5” x 7”: The Writer at His Desk. Papers are piled all around him, one sheet protruding from the typewriter carriage, over which he’s thrown a lanky forearm as if to keep his words to himself. On the desk a cigarette burns in an over-flowing ashtray. He is half-smiling, looking content, tired and oh, so familiar. I can’t help it, I thought. Bad father be damned. This man — the one with the rheumy blue eyes, the fingers as nicotine-stained as that reddish moustache, his front paunchy and his back hunched — this man I had liked once, very much. Of course, recollecting this does not mean I can or will revert to my childish, uncritical defence of him. No. I’m still prickly enough to note, for one thing, that this picture reveals a desktop cluttered only by cigarettes and the jumbled pages of works in progress: where are the mementos, the framed photos of any of his seven children, even the last of his three wives? As a parent myself now, I do not accept that my father should have felt free to make many of the choices he made. Nor do I believe that one is any less accountable for harm done indirectly, by the withholding of care, than one is for damage willfully achieved. Indeed, my experience suggests that the unintended outcomes may be the ones we regret most earnestly. But as a writer — a term I d0 not apply to myself until my father has been dead for decades — I see that the point of examining this man’s life and his writing is not to judge but to understand.

When I first sat down to write my way through these reflections, I felt overwhelmed by a riot of emotions. Where possibly to begin? I sat at my desk, hands frozen in the air above the keyboard for a long, long time. And then it hit me. Quite apart from any literary merit of my father’s fiction, his box of papers has reinforced the significance in my life of typed words. I thought, How apt it would be for me to move off this computer and dust off my father’s old manual typewriter. I would have to do some repair work before it would be serviceable: I recalled that the ribbons were last left in a tangled heap when my young daughters, guilty, afraid of angering me when they went too far playing with this ancient relic, had hastily stuffed the whole mess far into the back of our attic closet. I found it, of course, and shrieked in my most aggrieved voice — half-victim, half-tyrant — “That is not a toy!” When I knelt down to get a better view of the damage, I felt quickly defeated by the gnarls before me and returned the typewriter to the closet deep. But now, years later, I thought it might be time to drag it out and tackle those knots again.

My father earned his living for over thirty years by pounding away at the keys of any number of typewriters, but I like to think of this old manual, a portable Olympia, as his truest companion. More than seventy years old now, in its two-toned teal and off-white hard-shell case, the Olympia looks like a small, abandoned suitcase. It is certainly better travelled than I am. I can’t describe its earliest days in the late 1950s, although I’m sure they were unorthodox. During the sixties I know it to have led an energetic if divided life, mostly domestic, occasionally wild: it camped, canoed and caroused its way on “assignment,” into the BC interior, north to gold-rush country, all up and down, on and off the islands of the west coast. It cruised out of Vancouver’s Coal Harbour in 1971, crossed through the Panama Canal, stopped overnight in Venezuela and at several ports-of-call in the Caribbean, and disembarked from the ship finally in Holland. And then the little bugger got really lucky, caravanning throughout Europe and North Africa for more than a year before settling in for an enviable if frugal stay in a ground-entry flat in Hendon Lane, off the North Line in London, the city in which my father chose to hack away at his craft for another year and more, and to which my much poorer mother would in time send my brother and me for our month’s visit. By the time this dependable, mechanical friend flew back with my father from Heathrow to Vancouver in 1974, the two had collaborated on countless business and arts articles for newspapers and magazines in England and Canada, at least two novels, a half-dozen short stories, some memoirs, reviews, screenplays, interviews, résumés, and “pitch” letters to publishers, pleading (with varying degrees of humility) for support for any number of fledgling projects.

It was on this typewriter, in fact, that my father composed the occasional letter home, to me, and it is for this sentimental reason alone that I kept it after he died, even though by the mid-1970s he had moved on to electrics. By 1981, he was working at an IBM Selectric, the kind with those removable font-balls, little globes, each one containing an entire alphabetical world. The very impermanence of any one of those fonts, the temporariness with which a ball could be chosen, makes it hard for me to imagine my father striking the keys of that, his final machine, with anything of the trust or fondness I believe he shared with the Olympia.

I would like to say something romantic here too about the noise of my father working — a wistful, nostalgic claim, for instance, that my child’s ear could detect from the Gatling-gun report of my father’s one-hundred word-per-minute flying fingertips that all was right with my world. But I cannot call up this sound from my early childhood, those first five years when I shared houses with this man and his beloved machine. He surely wrote then, daily — he must have done, since it was by his wits that his six children, his ex-wife, his second wife and he himself lived. But he was not a man to be at home much. Truth be told, my father was not a man to keep any home for long. Although his long-term relationship with the Olympia might suggest otherwise, my father was simply not long on commitment.

So I guess I continue to hang on to this typewriter because it is evidence I have sorely wanted that my father was capable of stability, of loyalty, of love. When I was five years old, he and his Olympia moved on without us, without me. What does it mean that no matter how often I move, I lug the old portable along? If I am ever truly to journey out to meet the writer who was my father, as he represented himself on the page, and to others — to writers, lovers and friends — I must deal with the private symbolism of this machine. It is not his particular words but language itself that my father chose as his closest companion, writing the preferred mistress who alone got to accompany him on his solitary way.

That I turn to the keyboard myself when I crave understanding — or to be understood — is a complex irony not lost on me. We are kin, Don Stainsby and I. As his daughter, I have read my way back to scenes of unremembered love and over-vexed anguish, and remain deeply ambivalent towards all these memories. As a writer, I am grateful for the emotional imagination that infuses these inward travels. While I hope I’ve raised my daughters to know that they trump writing like paper swallows rock, I admit that I — like Munro’s Hugo, like my father — am often guilty of seeing life as so much “material.” I find myself rummaging through my “bank of memory” as well as this box of my father’s yellowed pages, turning over the “scraps and oddments” of early life to reveal what might become “ripe and usable”[1] in art. Understanding this now, I see that this archival pilgrimage has been a journey I have long needed to make.

*

Meg Stainsby (SFU Graduate Liberal Studies cohort 2000) submitted “Writing My Father” (under former title, “Writing Home”) in 2002, for LS 829: Directed Study. With Professor David Stouck’s company, Meg read her way through the dusty literary estate of her father, Donald Stainsby (1928-1981): Vancouver newspaperman, magazine editor and novelist. The archive documents the relationships and accomplishments of an aspiring man of letters — friend through the 1950s to 1970s of then-emerging CanLit notables such as Earle Birney, Margaret Laurence, Ethel Wilson and Alice Munro. As daughter, though, Meg contrasts the man’s devotion to the writing life against her experience of him in private, as father. Her personal essay reflects the influence of Donald Grayston’s course, LS 813: Pilgrimage and Anti-Pilgrimage, taken at the same time Meg was wandering through the carbon-copy tracings of her father’s career. Meg is currently pursuing a Phd in Creative Writing at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David (Lampeter, Wales), writing a memoir about post-traumatic stress and family. She and her rag-doll kitten split their time between Vancouver and Salt Spring Island.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1]Alice Munro, “Material,” Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You (Scarborough, ON: Signet / McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1974), 36.

9 comments on “#876 Stainsby’s carbons and files”

Dear Ms. Stainsby,

Thank you for this very nice article!

I am pleased to contact you today, as I am looking for information on an article by your father Donald Stainsby, as part of research for the animated documentary film I am preparing.

I was wondering if there were any archives surrounding this article by your father. Would you be willing to discuss this?

I thank you warmly for your attention.

Brilliant, Meg. What a remarkable piece. Beautifully beautifully written and so powerful.

A brave piece, deeply moving and instructive. You are your father’s daughter in your ability to turn chaos into order through words, the medium we all live in, writers or not. And when those words are well chosen and well ordered, as here, they give us that pleasure that comes only from fine writing.

A finely nuanced piece that captures the ambiguities of a vexed, traumatic, transformative relation of a father and a daughter. Stainsby’s anti-pilgrimage to connect with her father through her own writing, preserves his literary legacy while shedding light on an important era in Canadian literary history.

Thank you, Ms Stainsby and Richard … The memories shared enthral me, by reminding me of my attachments over a lifetime. (Worst of reasons to admire a daughter’s memories of a father? Probably.) At my beginning, as an adult, was The Ubyssey and, through it, an apprehension about Vancouver as literary metropolis. In my later years was SFU’s graduate liberal studies program. What’s not to like/love?

Thanks for this insight into a complex man. I knew Don when he was editor of BC Outdoors, when he helped me through a difficult time in my own life. I know he used some of my photos and articles so I could keep going and pay MY rent and MY support payments. When he passed I went to his funeral with the intention of telling that part of what I knew of him — but when I was there and faced with the casket I did not speak up. I knew nothing of his personal life beyond sharing a beer or lunch. For me he was simply the quintessential editor.

A lovely read — but especially for someone who has also struggled with a father’s archives and a collection of vintage typewriters.

Thanks Meg for this variegated distillation of so many things relating to the portal figure of your father. To all those writers that wish they hadn’t had a plumber or accountant dad, this memoir is cautionary wisdom that should put the brakes on that notion. I thought this was a fearless swath of writing, like jumping off a lakeside cliff hoping to hit the water and not the rock’s edge. Great leap and nice splash! What a delight to read your work.

The Ormsby Review strikes again. Thanks to Richard Mackie too.