#875 Chinese but not Chinese

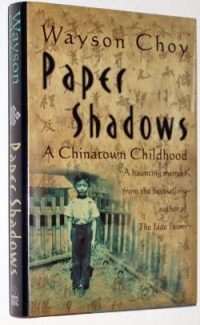

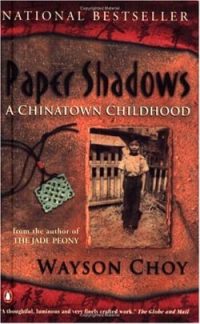

Paper Shadows: A Chinatown Childhood: A Memoir of a Past Lost and Found

by Wayson Choy

Toronto: Penguin Random House, 2018 (Penguin Modern Classics); first published by Viking Penguin, 1999

$21.00 / 9780735234666

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

When I was six years old, ostensibly as a non sequitur, I announced, “I’m English!” to every family member circling the lazy Susan in the Chinese restaurant. The ensuing laughter was sufficient for me to discern that not only had I said something inadvertently funny, but that I was colossally wrong in my understanding of how I was seen in the world. I was decidedly not English, no matter how well I spoke it; I was, irrevocably and visibly, Chinese. No escape.

When I was six years old, ostensibly as a non sequitur, I announced, “I’m English!” to every family member circling the lazy Susan in the Chinese restaurant. The ensuing laughter was sufficient for me to discern that not only had I said something inadvertently funny, but that I was colossally wrong in my understanding of how I was seen in the world. I was decidedly not English, no matter how well I spoke it; I was, irrevocably and visibly, Chinese. No escape.

With uncanny similarity to my blundering six-year-old declaration, Choy writes of a moment where he tells his mother that he speaks Chinglish — a catchy portmanteau of Chinese and English. His mother is not impressed. It is not often that I feel a genuine shiver of recognition, but I did with Wayson Choy’s Paper Shadows.

Paper Shadows is an eminently readable memoir that begins with a suspenseful premise: shortly after Choy’s publication of The Jade Peony (1995), he receives an enigmatic phone call from a woman who reveals that Choy was adopted. Before learning much more, we are treated to a telescopic lens view of Choy’s childhood that often uncomfortably reminded me of my own, while also tangibly reminding me that that no matter how archetypal a child of immigrants story is, there are always particularities.

Choy’s prose is clean and precise. Ghosts are mentioned often and in a matter-of-fact way that never seems supernatural or hokey; sometimes the ghosts are, colloquially, simply white people (bak kwei). The anagnorisis of his homosexuality during an innocuous childhood game is the opposite of overwrought, indeed it is downright sparse to the point of being vaguely dissatisfying, not to be referenced again until the end (“Forever after, I knew — without shame — something about my sexuality that I was not able to fathom until fifteen years later)” (p. 337).

A young Choy recounts his fixation on opera, only to fall for the more stereotypical Western masculinity of cowboys. When his grandfather shows him how to urinate, it is an emblem of masculinity successfully emulated, even a point of pride. Choy’s introduction to Snow White and the Seven Dwarves is intended to showcase the dwarves’ work ethic to inspire Choy, but the joke is on Choy’s guardians — he favours Dopey. He writes both comedically and heartbreakingly of the tribulations of inadvertently training his dog, Winky, to urinate in a different place in the house; frequently, Choy is reminded by his elders that Winky is “better fed in Gold Mountain than people were in China” (p. 212). Choy is most palpable when he depicts the often alienating experience of not being adequately, properly, Chinese, while also being ineluctably, damningly Chinese. Repeatedly, adults remind him that he is Chinese, perhaps with actual fear that he might forget.

When people ask me what my first language was, I usually tell them English. It’s true, but it wasn’t the only one. I grew up trilingual, speaking Mandarin, Cantonese, and English with a fluency I can only dream of now. Once I was enrolled in preschool, English took precedence. I became a precociously nocturnal, incurable bookworm, a deeply myopic one at that. I associated anything Chinese with my parents, and my parents were anathema, but none of this cultural disassociation could undo the visibility of my heritage. I could no longer have a proper conversation with my grandparents besides nodding and basic words. For years, I went to Mandarin classes on Saturday, where I struggled to fit complex brush strokes in what struck me as unreasonably tiny squares (my handwriting is also insufferably large in English: I suspect my penmanship betrays my Napoleon complex). I can safely attest that I learned not a single thing. I was an irrevocable banana: “yellow on the outside and white on the inside” (p. 84).

Choy, meanwhile, had the audacity to play hooky in Chinese school — I only wish I’d thought of that. It was a disarming pleasure to read this frank account of a Chinese student largely unrepentant for being lackadaisical in Chinese school, in contrast to the usual stereotype of a diligent model minority on the fast track to becoming a doctor or a lawyer. Choy writes of harbouring a fantasy of burning the school down, which comes across as more childish than chillingly evil; he is brought down to earth from his pyromania fantasies when his father asks, quite simply, what the building is made out of, decimating his plans.

A fellow classmate in their ill-fated, practically compulsory sojourn to Chinese school says, “Don’t you want to be Chinese?” The implication is, of course, that speaking Chinese is being Chinese (conversely, the same logic for speaking English and being white or even white-adjacent, does not apply). Choy writes, “ . . . how could I ever be Chinese?” (p. 238) Out loud, he responds by telling his classmate that he is Canadian, a pronouncement that is met with confusion and pity.

Although initially shamed for his less than auspicious performance in Chinese school, Choy is eventually reprieved from it, and later writes: “Less and less was said about taking Chinese lessons. There were other ways to be Chinese.” These other ways are not specified or delineated, but that may be for the better to avoid the finitude that other people are so willing to impose on the narratives of people of colour.

Choy has no shortage of family secrets rife with discord and unhappiness — for instance, learning as an adult about the existence of his father’s two sisters and his grandfather’s acrimonious second marriage to an upper-class woman with bound feet. His adopted status was a secret kept only from him. Historical records are irretrievably destroyed. It is considered vaguely miraculous that Choy unearths anything at all; his Aunty Freda says, “It’s surprising we know anything . . . the old Chinatown people were so secretive” (p. 338). Choy asks with magnanimity, “Whose life, I wonder, is not an endless knot?”

When a childhood friend of Choy’s recounts a violent encounter with a stranger that Choy believes he himself would not have survived, Choy learns that his friend pictured him while he was fainting. He learns that he was, from his friend’s perspective, responsible for his survival. The interpretation confounds Choy: “I thought to myself, one’s life should always be read twice, once for the experience, then once again for astonishment” (p. 332). Although I’d stipulate that the responses are not mutually exclusive, one might wonder why astonishment might occur the second time when there is presumably less novelty; however, astonishment is not reserved for surprise parties or gruesome murders, but rather, it can arise from ruminative insights gained from experience — retrospective marvelling requiring one to reassess one’s self — as Choy does with his own personal history.

Bound with more untied knots than tied knots, Paper Shadows is not a crime novel but a memoir worthy of our attention and, certainly, of being read at least twice.

*

Jessica Poon is a writer, line cook, and pianist in Vancouver. She recently completed her bachelor’s degree in English literature from the University of British Columbia. Visit her website here.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster