#868 Hazelton mission and medic

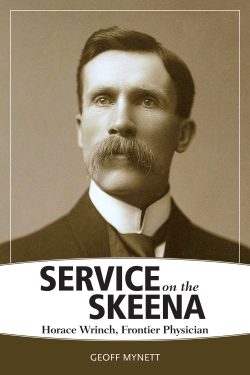

Service on the Skeena: Horace Wrinch, Frontier Physician

by Geoff Mynett

Vancouver: Ronsdale Books, 2020

$21.95 / 9781553805755

Reviewed by Tyler McCreary

*

Service on the Skeena, Geoff Mynett’s first book, presents the story of the northern medical missionary, public healthcare advocate, and later provincial politician, Horace Wrinch. The first doctor to serve Gitxsan and Wetsuwet’en territories, Wrinch lived through the early twentieth-century transformation of British Columbia’s northwest interior.

Service on the Skeena, Geoff Mynett’s first book, presents the story of the northern medical missionary, public healthcare advocate, and later provincial politician, Horace Wrinch. The first doctor to serve Gitxsan and Wetsuwet’en territories, Wrinch lived through the early twentieth-century transformation of British Columbia’s northwest interior.

Mynett, a retired lawyer and husband of Wrinch’s granddaughter, Alice, had privileged access to family histories. However, Mynett primarily relies upon a careful reading of the regional newspaper, the Omineca Herald, to construct a social history of events in the northwest interior. He supplemented these articles with records from the British Columbia Provincial Archives, the United Church Archives in Vancouver and Toronto, and the Library and Archives Canada. Through this rigorous study, he portrays a compelling account of Wrinch’s life and work.

Born in 1866, Wrinch grew up on a farm in Essex, England. He immigrated to Canada in 1880, attending St. Francis Agricultural College in Quebec. After graduating in 1884, he joined his brother on a farm in Trafalgar Township (in contemporary Oakville), Ontario.

Baptized Anglican, Wrinch became a Methodist in 1888. As described by Mynett, it “was the most important event in his life. His actions thereafter were governed by his understanding of God and by the need to help others in body and in spirit” (p. 20). The Methodist Church “was, above all, a church that emphasized the duty to perform practical service for the community” (p. 21).

In the early 1890s, Wrinch committed to take up medical missionary work. Explaining his decision, Wrinch stated, “I believe missionary work to be the highest form of service in which one can engage” (p. 23). Preparing for his service, Wrinch first matriculated from the Methodist Albert College, then completed his studies at Trinity Medical College in Toronto.

In 1900, when Wrinch first arrived in the northwest interior of British Columbia, it remained an isolated region with a few thousand residents. The Indigenous Gitxsan and Wetsuwet’en peoples predominated, although the settler population would expand through Wrinch’s three decades in the north.

When Wrinch arrived, Hazelton was the central settler community. Originally formed in 1866 as a fur trading post, the town had expanded to equip mining prospectors during the brief Omineca Gold Rush in the 1870s. The local population remained small, accessible by sternwheeler only in the summer months.

The exposure to European diseases in the late nineteenth-century had devastated Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en populations. They had experienced the ills of Western civilization but received few of its benefits. Aiming “to heal their bodies as well as their souls,” Wrinch believed that he could cure their maladies and instruct them in “a good Christian life” (p. 56).

Mynett documents how Wrinch’s medical mission inaugurated a regional conflict “between the scientifically trained doctors and the Gitxsan shamans or halayts” (p. 131). The author provides a relatively balanced account of this conflict, highlighting how Wrinch sought “to prove his medicine effective and thus reduce the power of the halayts, who, in turn, did what they could to reduce his credibility” (p. 133).

Mynett is sensitive to the importance of the halayts “to the spiritual life of the Gitxsan,” integrating more recent scholarship on Gitxsan healing traditions into his analysis. He is also critical of how Western medical authorities denigrated “halayts as witch doctors, frauds and conjurors” (p. 131).

However, Mynett’s account flattens the substantial power asymmetries that structured the Gitxsan encounter with modern medicine. While both medical missionaries and halayts battled for authority over the spirit and body, there were stark imbalances in this struggle. The Canadian state criminalized Indigenous healing practices, forcing them underground. Such imbalances enabled Wrinch to feel secure in the supersedence of Indigenous by Western medicine, for instance, celebrating in a 1907 report the decline in the Gitxsan’s “old superstitious fear of our medicine” and reduced employment of their “witchcraft methods of doctoring” (p. 136).

Mynett positions Wrinch’s sanctimonious attitude as a product of his times, noting the presumption that Indigenous traditions would simply fade away was ill founded. Indigenous traditions endured. As Mynett documents, another medical missionary, Geddes Large, reported in the mid-1920s that halayts “drumming and rattling over patients was still common” (p. 135).

Positioning colonial mentalities as bygone, Mynett understates the endurance of white supremacy. As I write this review, the presence of Black and Indigenous protesters in the streets is testament to enduring racial tensions across North America. If Mynett understates the continuity of racism, he nevertheless effectively documents the social and infrastructural changes that remade the provincial north.

When Wrinch arrived, regional transportation networks centrally relied on sternwheelers, canoes, horses, and mules. By 1936, when he retired and left the northwest interior, roads and railways, as well as the introduction of electricity, had redefined social life in the region. Solitary prospectors had been replaced by increasingly capitalized industrial mining projects. The north was becoming evermore integrated into the provincial economy.

Wrinch was an active participation in these transformations as a two-term President of the BC Hospital Association, two-term Liberal representative in the Provincial Legislature, and member of the provincial advisory Economic Council in the 1930s. Documenting Wrinch’s many community and political engagements, Mynett stresses his transformation over time from a Methodist missionary to an ecumenical community leader. Mynett particularly emphasizes the doctor’s passionate early advocacy of a public health insurance system in the province. Despite repeated government commissions and a public referendum supporting the introduction of public healthcare, a program was never implemented during Wrinch’s tenure. However, his determined advocacy helped build public support and political will for an eventual legislative change.

Ultimately, Mynett presents a very sympathetic image of Wrinch. His account at times glories in the sensational moments and figures of local history — for instance, the Simon Gunanoot murders and the subsequent decade-long manhunt. However, Geoff Mynett’s Service on the Skeena: Horace Wrinch, Frontier Physician is not simply a hagiography of the great men of the Skeena. Most compelling is how Mynett, through recounting Wrinch’s life, presents a broader account of the transformation of a northern community through the early twentieth century.

*

Born and raised in Northwestern British Columbia, Tyler McCreary is an assistant professor of Geography at Florida State University, and an adjunct professor of First Nations Studies at University of Northern British Columbia. His research examines how Indigenous-settler relations configure the politics of land, labour, and community life. He has analyzed how environmental governance processes address Indigenous relationships to the land, how Indigenous peoples interact with resource sector labour markets, and how processes of urban and regional governance impact Indigenous families living in towns and cities. He has published over two dozen scholarly articles and book chapters. He also recently coedited (with Heather Dorries, Robert Henry, David Hugill, and Julie Tomiak) the book, Settler City Limits: Indigenous Resurgence and Colonial Violence in the Urban Prairie West (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2019). For a review of his first book, Shared Histories: Witsuwit’en-Settler Relations in Smithers, British Columbia, 1913-1973 (Smithers: Creekstone Press, 2018), see The Ormsby Review no. 440 (December 5, 2018), by Keith Smith. Shared Histories won the BC Historical Federation’s Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for Historical Writing for best book published in 2018. Editor’s note: Tyler McCreary has also reviewed books by Robert Budd & Roy Henry Vickers and Keith Thor Carlson et al. for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “#868 Hazelton mission and medic”

My mother Muriel Webster (nee Jeffers) worked at this hospital from I think 1939 to 1943, perhaps earlier or longer. She nursed for Dr. Eric Austin but our family was close friends with a family name of Wrinch who lived in Moncton NB Unsure of any connection but their daughter, Lee was also a nurse. My dad was born in Calgary (1915) but the family moved up north in the 1920s? and one relation Isabelle Webster was mayor of Hazelton. Her husband Harry was a heating and cooling sales and installation man in the area, living in Hazelton on the banks of the Skeena at a bend in the river. I remember as a 3 yr old visiting my grandparents’ log house and in 1970s the remnants were still there. Dad, David Albert, started out work by painting the wooden flag pole in front of the agency building. Had to climb up without spurs took two days I believe His sister, Peggy, married a Bartlett and moved to Terrace where they had 3 children. Two of their granddaughters (twins) now work for BC Ferries, one a Captain other an engineer but may also now be a Captain. I must get the book and read about the history before my mom, a graduate from Royal Jubilee (1938?) went north.