#865 Channelling Oscar Wilde

Beautiful Untrue Things: Forging Oscar Wilde’s Extraordinary Afterlife

by Gregory Mackie

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019

$60.00 / 9781487502904

Reviewed by Brittany Reid

*

There has long been a fascination with the unusual lives of authors, leading to the proliferation of a popular and academic genre known as literary biography. Literary biographies are intended to offer privileged access into the lives of writers, making them at once more human and more exceptional. Authors of literary biography are thus tasked with recreating the conditions that led to their subject’s literary composition and revealing points of connection or causality between that writer’s life and writing. However, there are unique challenges associated with reviving the textual corpus of historical authors. To reanimate the spirit of long-dead writers, creators of literary biography are required to perform a kind of symbolic séance, reanimating the author as a living body of work. Accordingly, scholars in this genre are presented with the additional challenge of re-situating their subjects’ lives and writing, while also reviving them for new, modern audiences.

There has long been a fascination with the unusual lives of authors, leading to the proliferation of a popular and academic genre known as literary biography. Literary biographies are intended to offer privileged access into the lives of writers, making them at once more human and more exceptional. Authors of literary biography are thus tasked with recreating the conditions that led to their subject’s literary composition and revealing points of connection or causality between that writer’s life and writing. However, there are unique challenges associated with reviving the textual corpus of historical authors. To reanimate the spirit of long-dead writers, creators of literary biography are required to perform a kind of symbolic séance, reanimating the author as a living body of work. Accordingly, scholars in this genre are presented with the additional challenge of re-situating their subjects’ lives and writing, while also reviving them for new, modern audiences.

In the case of Beautiful Untrue Things (2019), Gregory Mackie provides a literary biography of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) that succeeds in these aims by honouring his life, writing, and persisting fame. But while there is an efflorescence of biographies based on the life of this canonical Irish writer, Mackie offers a distinctive and innovative treatment that pays fitting tribute to his subject’s exceptional legacy. To accomplish this task, he inverts the traditional structure of literary biography, minimizing the particulars of Wilde’s life and instead emphasizing both his afterlives and the lives of those worked to preserve his memory. Consequently, the focus of Beautiful Untrue Things is not Oscar Wilde as he lived, but the spectral presence of “Oscar Wilde” as he continues to haunt our modern literary landscape.

While Wilde’s afterlives persist into the present, Mackie focuses his study by investigating the proliferation of “a more dubious set of Wilde fans who were operating in the 1920s in Dublin, New York, and Paris” (p. 5). He outlines how efforts to reclaim Wilde’s cultural status during that time led to an archive that provided ample material for “the production of a remarkable sequence of Wilde fakes – or, indeed, fake Wildes – that began to appear in both print and manuscript with increasing frequency in the 1920s” (p. 6). As he further asserts, these forgeries can be considered “the early modernist versions of phenomenon that we would today call the cult of fandom” (p. 6). This refocusing destigmatizes the practice of literary forgery, recasting these “fake Wildes” as Wilde fans.

A foundational principle of Beautiful Untrue Things is that artistic forgeries of Wilde’s writing are not necessarily lesser, unethical forms of creation. While this reading is consistent with the view of many contemporary theorists who similarly suggest adaptation is a creative and interpretive act, such as Linda Hutcheon and Gerard Genette, this argument can be difficult to accept at first glance, especially when perceived through the lens of copyright law or artistic appropriation regarding marginalized voices. However, Mackie resituates this discussion within its historical context, arguing that these Wilde forgeries helped resuscitate his cultural legacy after his reputation was tarnished, due to the 1895 indecency trials and his subsequent incarceration. Furthermore, he concludes that these forgeries not only preserved the author’s place within the cultural consciousness, but also reflected Wilde’s own emphasis on theatricality, aestheticism, and self-construction.

Beautiful Untrue Things offers both a general introduction to the cult of Wilde fandom and exemplary case studies that illuminate the lives and practices of key forgers, including “Dorian” Hope, Hester Travers Smith and her spiritualist circle, and “Mrs. Chan-Toon.” Each of these examples reveals a unique character that sought to reembody Wilde, sometimes literally, and adopted his name as a form of creative cosplay. Additionally, each of the book’s chapter titles “borrows its heading from a Wilde title – then reforges it,” allowing Mackie to express his own position as a descendent of Wilde and his own role within this chain of influence (p. 28). Through his use of book and theatre history, he casts “these figures as players in an ongoing drama whose absent star they alternately impersonated, appropriated, and defended” (p. 28). Furthermore, he makes a compelling case for “how literary forgery can also come into view as a form of performance art” (p. 7).

Implicit within this discussion of performance and identity, especially in the context of “the queer coordinates of Wilde’s authorial persona and legend” (p. 29), is contemporary criticism regarding performativity, such as the work of Judith Butler or Richard Schechner. By adopting this position, Mackie reinterprets forgery as a transgressive act of identity formation, which has allowed subsequent generations of Wilde fans to recast themselves in their hero’s image. While he acknowledges the commercial benefits of their duplicity, he focuses on the positive effect they had on Wilde’s position within the cultural consciousness and how “in their writings, impostures, scams, and dodges they forged, collectively, an extraordinary afterlife for Mr. O.W.” (p. 5).

Beautiful Untrue Things offers an insightful and fascinating exploration of Wilde’s many afterlives. Through well-selected case studies, Mackie illuminates key forgers, while introducing a myriad of others for further and future exploration. For readers new to Wilde and unfamiliar with his literary and theatrical oeuvre, Mackie offers necessary background to introduce his life and writing. For scholars of Wilde, Victorian literature, or Modernism, Beautiful Untrue Things provides an incisive discussion of this key figure, by both resituating him within his cultural context and reframing him for twenty-first century readers. By focusing on the forgers rather than the forged subject, Mackie details the processes of myth-making and not their hagiographic results.

What remains is a collective biography that focalizes the experiences of readers, recipients, and responders instead of Wilde as the original author. Resultantly, Wilde and his work are celebrated and preserved by tracing his influence through those he inspired. Ultimately then, Beautiful Untrue Things reveals itself to be a sleight-of-hand maneuver that confounds any attempts to mythologize Wilde as a singular literary genius. Instead, Mackie unveils his intentions to create a prosopography that resurrects Oscar Wilde, alongside those who were willingly possessed by his spirit.

In this way, instead of explaining Wilde’s import by recounting the documentary record of his life, Mackie follows his subject’s lead by creating a literary biography that is itself an artful reflection on Wilde’s haunting cultural legacy.

*

Dr. Brittany Reid is an Assistant Teaching Professor in the Department of English and Modern Languages at Thompson Rivers University. Her research broadly explores nineteenth-century literature, theatre history, and sport literature. Her doctoral research was a performance-as-research project based on contemporary Romantic Biodramas: theatrical adaptations of Mary and Percy Shelley’s lives and writing. Current projects include upcoming chapters in Frankenstein’s Lives: Shelley’s Novel as Cultural Phenomenon and Polyptych: Adaptation, Television, and Comics. She is also the co-host of Body Paragraphs, an academic audio series that explores convergences between sport and literature, and co-editor of the interdisciplinary collection “Duelism:” Confronting Sport Through Its Doubles.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#865 Channelling Oscar Wilde”

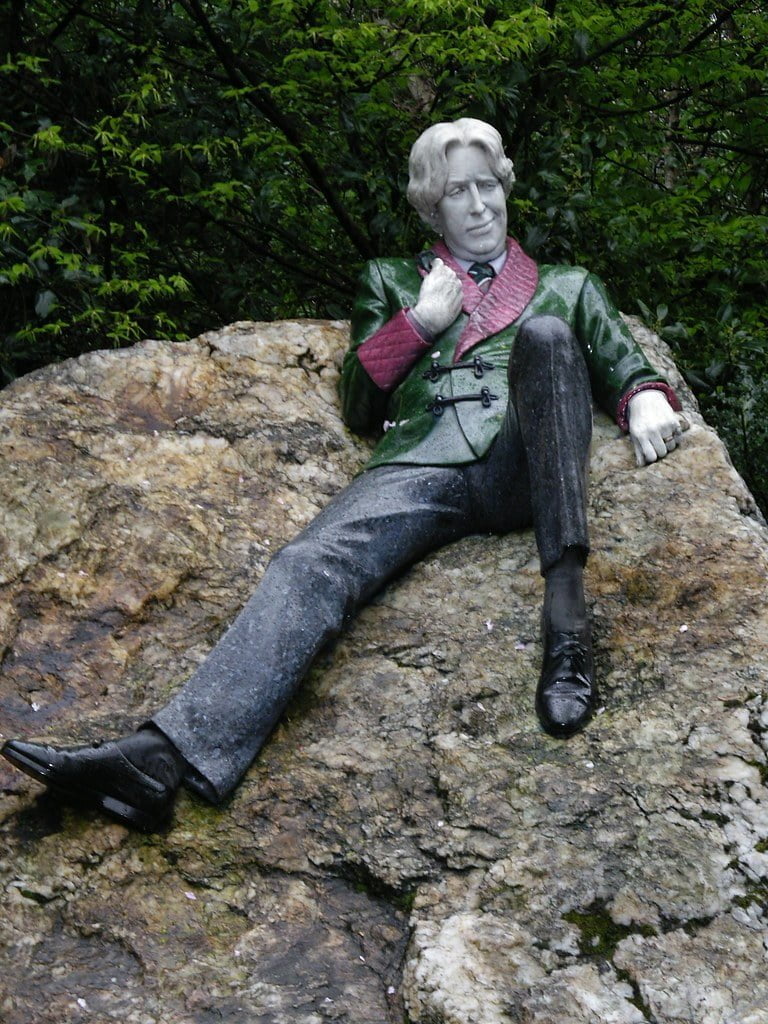

Good piece Brittany. Readers of TOR might like to know that the picture in the review featuring the “statue” of Wilde in Merrion square has a BC connection. The torso/jacket of the reclining figure was made from BC jade by sculptor Deborah Wilson of Vernon, BC. Danny Osborne is the man that did the rest of the sculpture and gets the credit but Wilson did the very tricky and standout signature jacket of Wilde.