#849 The BC coast by wooden boat

Becoming Coastal: 25 Years of Exploration and Discovery of the British Columbia Coast by Paddle, Oar and Sail

by Alex Zimmerman

Cocoa Beach, Florida: Seaworthy Publications, 2020

$34.95 / 9781948494274

Distributed by Red Toque Books and available at independent bookstores

Reviewed by Brian Harvey

*

Coastlines are elemental. They offer both access and exit, entry and escape. The step from land to sea is like no other, and it’s one that adventurers have been taking for as long as people have found themselves confronting the water. In Denmark, you’re never more than thirty miles from the sea. Denmark is rated one of the happiest countries in the world. Maybe there’s a connection.

Coastlines are elemental. They offer both access and exit, entry and escape. The step from land to sea is like no other, and it’s one that adventurers have been taking for as long as people have found themselves confronting the water. In Denmark, you’re never more than thirty miles from the sea. Denmark is rated one of the happiest countries in the world. Maybe there’s a connection.

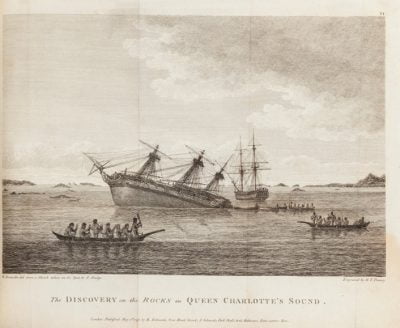

The coast of British Columbia has been irresistible to adventurers since the charting explorations of Captain George Vancouver. Vancouver’s multiple expeditions, between 1791 and 1795, resulted in the British Admiralty charts that made it possible for a trickle of adventurers to build to a steady stream and then to a torrent. Adventurers became settlers. They opened the coastline to development that tumbled the original inhabitants out of their canoes and longhouses and into two centuries of violent readjustment to a game without rules.

Vancouver’s charts were replaced – modified, really, because nothing he did needed to be thrown away, just refined. There are still uncharted rocks from San Francisco to Alaska (the astonishing area Vancouver covered), but one by one they are outed by unlucky mariners or by the inexorable triple-beam sonar scanners of the Canadian Hydrographic Service. Onto the chart they go. Even though most boaters now find their way by satellite and GPS, you can still buy a paper chart that bears no small resemblance to Vancouver’s version. Legally, you have to carry paper charts for every place you go.

Today’s coastal adventurers are less motivated by country or commerce and not all are satisfied with just taking photographs. Many are also driven to write. This urge is understandable; the coastline is staggeringly beautiful. But it’s that very novelty and beauty that’s the downfall of so much of what gets written about travelling the coast by boat, because there is so little that is not exceptional. It’s all good, but there’s an awful lot of it, and there’s a limit to the available superlatives. And the basic elements are the same whether you’re in an anchorage in the southern Gulf Islands or Nootka Sound. This means that writing about a trip from one bay to the next cannot be simply about getting there (unless, like Captain Vancouver, getting there is your mission).

How do you write entertainingly about voyaging along the British Columbia coast, assuming you’re not just writing a guidebook? Jonathan Raban covered much of the same territory as Captain Vancouver in his Passage to Juneau (1999), and he threw the armament of ten previous books of erudite travel writing at this book. He jumps nimbly from sailing arcana to local colour to a precis of the many improving books he brought along on his trip, inserting events from his childhood and even throwing in a quick trip to England to be with his dying father. If Raban has a constant companion on his trip it’s George Vancouver himself (he calls him Captain Van), whose monotonous journals he has brought along for consultation (and, I like to think, as a reminder of how not to write up his own trip).

How do you write entertainingly about voyaging along the British Columbia coast, assuming you’re not just writing a guidebook? Jonathan Raban covered much of the same territory as Captain Vancouver in his Passage to Juneau (1999), and he threw the armament of ten previous books of erudite travel writing at this book. He jumps nimbly from sailing arcana to local colour to a precis of the many improving books he brought along on his trip, inserting events from his childhood and even throwing in a quick trip to England to be with his dying father. If Raban has a constant companion on his trip it’s George Vancouver himself (he calls him Captain Van), whose monotonous journals he has brought along for consultation (and, I like to think, as a reminder of how not to write up his own trip).

Passage to Juneau is entertaining. Raban shows that you have to write about more than the places you visit. The boat itself is one place to start. If you travel along the British Columbia coast, the boaters you encounter are, for the most part, nice people with nice boats. Most are over thirty feet these days, and all the sailboats have auxiliary engines. Jonathan Raban’s sailboat would fit this description. But if you stay out long enough, and poke into enough interesting places, sooner or later you will encounter an outlier. Someone in a very small and engineless boat, paddling, rowing or sailing through weather you’re congratulating yourself on negotiating in your own thirty-five footer, or beached, alone, in some tiny notch that no glossy cruising guide would even bother with. Someone like Alex Zimmerman.

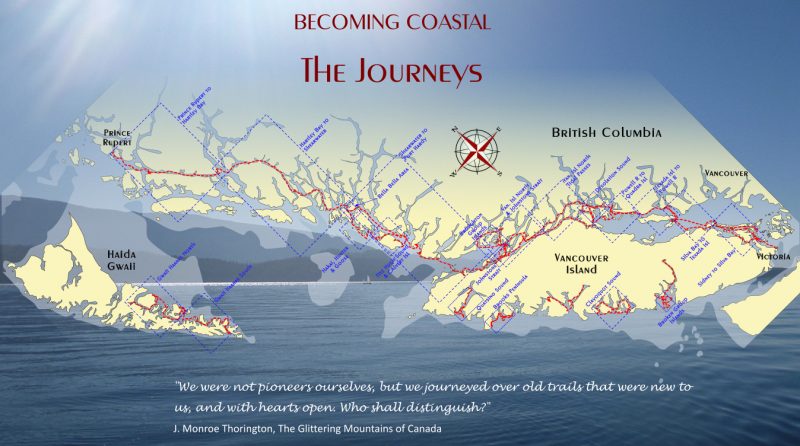

Zimmerman’s new book Becoming Coastal: 25 Years of Exploration and Discovery of the British Columbia Coast by Paddle, Oar and Sail describes voyages ranging from the southern Gulf Islands to Desolation Sound, the Broughton Archipelago, Barkley Sound on the West coast of Vancouver Island, the Inside Passage and Haida Gwaii. Zimmerman did them all in very small boats.

Small boats have some advantages. A kayak, for example, is inherently seaworthy, in the sense that a twig will still be floating after a gale. Kayaks ride low, their paddles act like outriggers and by eliminating an engine such craft incidentally do away with the main source of constant worry and expense for most boaters. Many historic voyages have been made by canoe-like craft. Tilikum, which travelled most of the way around the world in 1901-1902, began life as a Nuu-chah-nulth canoe (and ended as a museum display in Victoria, where her voyage began). [See Mark Forsythe’s review of Around the World in Dugout Canoe here — Ed.]. The catch, of course, is that a kayaker has to time his travels exquisitely, picking weather windows, knowing not only when the tide changes but exactly how a current manifests itself from corner to corner in a tidal passage. These are things all boaters are supposed to pay attention to, but a big diesel engine is usually enough for most to believe they can punch through anything. And they usually can, until a speck of crud gets through the fuel filter and their two hundred horses are suddenly dead in the water.

After reading Alex Zimmerman’s book I have enormous respect for his accomplishments. I now understand the reason for that long subtitle: he has done a lot. Not only has he paddled a kayak, often alone, into a daunting number of nooks and crannies on the inside and outside of Vancouver Island, Hakai Pass. and Gwaii Hanaas, he did it not in one of those off the rack fibreglass touring kayaks whose cheerfully coloured hulls you see pulled up on beaches everywhere, but in kayaks he designed and built himself. One of them was even collapsible, which adds structural engineering to the long list of his skills. When he tells us that the bow of his kayak “buries itself in green water every second wave” (this is in Quatsino Sound), we know that travelling this way is extremely hard work. And very few people would be likely to paddle the Inside Passage, alone, when they’ve started to suffer from atrial fibrillation. (Zimmerman’s heart condition flares up, fittingly, near Gil Island, where the ferry Queen of the North sank in 2006).

When Zimmerman became older (remember, his book covers 25 years), he replaced the kayaks with a pair of self-designed rowing/sailing craft, which he also built. There are, for me, too few photos of these later boats in Becoming Coastal, because they are elegant, two-masted beauties that can be both rowed and sailed, while also serving as bedroom for a month’s cruising in any weather. At just under twenty feet, they look to me like slightly smaller versions of the longboats Captain Vancouver and his survey crew rowed away from the HMS Discovery to drop their lead line — the only way of measuring depth in those days — and so create those famous charts. It is a certainty that both Zimmerman’s and Vancouver’s longboats entered the same bays and glided over the same submerged rocks. That Zimmerman followed in Vancouver’s ripples, and did so in human-propelled boats of his own making, is an achievement few boaters could ever hope to match. He was also, if my calculations are correct, twice Vancouver’s age.

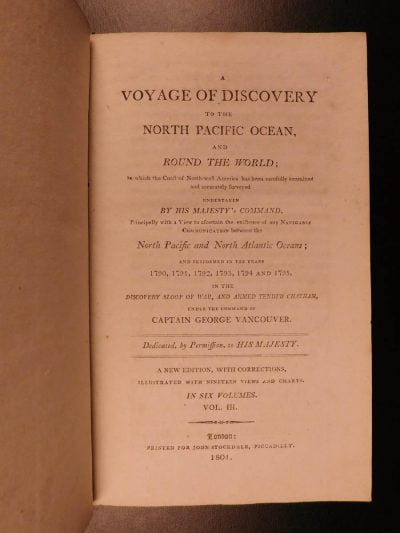

There is, however, another point of comparison between the endeavours of Vancouver and Zimmerman, which a reviewer is compelled to make. When Vancouver retired to Surrey in 1795 at the age of 38, he began to write the chronicle of his voyages in coastal North America, a labour left incomplete when he died at 41, beaten down by public attacks from a former officer and disease his forensic biographers have yet to diagnose. Vancouver’s Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World was finished by his brother John and runs to three volumes, each over 400 pages. A facsimile can be found here. Readers will quickly agree with Vancouver’s biographers in finding the account numbingly repetitive. Vancouver clearly wrote from the voluminous logs he was required to keep, recording weather, views, soundings, compass declination, supplies and encounters with Indigenous peoples (whose descriptive place names like “Rocky place not reached” Vancouver replaced with what Raban calls “a gigantic naval cemetery”).

More interesting are Vancouver’s interactions with others, such as the Spanish explorers Quadra and Galiano with whom he was required to engage in gentlemanly diplomacy over the respective claims of “ownership” of Nootka. There are gems, to be sure, and revealing ones, like this backhanded compliment for Chief Maquinna’s daughter: “Her skin was clean, and being nearly white, her person altogether, though without any pretensions to beauty, could not be considered as disagreeable.” But Voyage of Discovery is still a slog, as it had to be, because it wasn’t about George Vancouver, it was about the places he put on his chart. Zimmerman’s account of his travels, while shorter than just one of Vancouver’s volumes, also suffers from “too much place, not enough person.” Because no matter how extraordinary and impressive the process of going from A to B may be, the general reader will find A and B on the coast of British Columbia to be much alike. Beauty is not enough — in a low evening sun, even the diesel hose on a fuel dock is beautiful. It’s the author’s response to that beauty that readers want to know.

Yet over the 337 pages of Becoming Coastal I could form only a hazy picture of its author: single-minded, fearsomely resourceful, tough enough to put up with buttocks worn raw by rowing, convivial when called upon but capable of long stretches of aloneness and definitely a prolific note-taker. He seems to read a lot, but only provides two titles. There is no author photo, only two shots on beaches, in which the author’s head is the size of a pencil eraser. Of his stated desire to tell the story of his change from “Prairie boy” to mariner (the “Becoming” part of the title), I found myself inferring much, but actually reading little. William Zinsser puts it best when describing the writing of memoir in his indispensable On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction. He says, “The best gift you have to offer when you write personal history is the gift of yourself. Give yourself permission to write about yourself, and have a good time doing it.”

Zimmerman’s account of the docks at Minstrel Island, at the edge of the Broughton Archipelago, is an instructive comparison with that of Jonathan Raban. Zimmerman describes a frustrating week there (he was caught in a wind trap) as a long round of commiserations with other boaters. Raban was lucky enough to visit when the place still operated as a ramshackle hotel, and stuffs his account with lively if condescending descriptions of the loggers living there and, crucially, how he felt about them. Now, the hotel is abandoned and the docks are free to anyone who comes along, but the fading ruins of the place remain intensely evocative, and must have been so during Zimmerman’s visit too. I wish he had described how they affected him.

As a published book, Becoming Coastal has some minor shortcomings. Many of the place names on the maps that accompany the chapters are in a font size about the same as the emergency numbers on the back of a credit card, which is to say, unreadable. A single, small scale map of the entire coastline would help the reader immensely, because it’s often hard to tell where Zimmerman actually is. Puzzlingly, the names of the many animals, birds, fish and even plants Zimmerman encounters on his voyages are usually — but not always — capitalized. On a single page in the Broughton Archipelago, Zimmerman records Rhinoceros Auklets, Marbled Murrelets and California Gulls alongside strangely demoted Harbour porpoises and completely lower-case humpback whales. There are plenty of orcas in the book, but no Orcas. Irritants like these are easy fixes, but they should have been caught in an edit, especially for a book that costs $35.50.

As for the writing itself, Zimmerman is most effective on the rare occasions when he uses imagery. I loved his description of large power boats at speed, whose owners seem unaware of “the effects of the large holes they are dragging through the water.” Likewise the shoreside trees that “dip their elbows in the high tide.” Detail is so much more interesting when it’s functional, not simply descriptive, so I wanted much more in the vein of his excellent description of how the forest floor in the Broken Islands manages to stay dry even on a rainy day.

When Zimmerman likens the preparations of a paddler tackling the outer coast to those of a matador, he shows how well he can write. I could have done with a lot more of this kind of imagery (the Milky Way “a spilled bag of diamonds,” rowing “a kind of kinetic reverie”) and much less hour-to-hour detail on getting from A to B to C and on through the alphabet. We really don’t need that entire alphabet, and much of Becoming Coastal could have been tightened in favour of expansion of the unusual bits. When Zimmerman describes the horrifying collection of plastics he found on the Brooks Peninsula, I longed for a context-setting paragraph on plastics in the world’s oceans. And his narrative is not well served by being in the present tense, a technique that can lend urgency, but only if used sparingly.

Does an author’s parsimony regarding self-revelation diminish the work? In the case of Becoming Coastal, very little — but it does define the book’s audience. Zimmerman is extremely authoritative, something that cannot be said of many writers about voyaging. If I were to plan a kayak trip in, say, the Broughton Archipelago, I would not consult someone who paid for a kayak tour there, or even someone who has led one. I would turn to someone who went there alone in a boat he built himself. Alex Zimmerman has described his forays to the Broughtons and many other places in credible, practical detail. In this, he is George Vancouver’s heir. Anyone thinking of following him to any of these wonderful destinations should buy a copy of Becoming Coastal before even buying a boat.

*

Brian Harvey grew up on the West Coast of Canada and trained as a marine biologist. He began writing newspaper columns and science-travel articles for magazines in 1997. His first book for a general audience (The End of the River) was a Globe and Mail “Best 100” book for 2008 and was followed by two works of fiction (Beethoven’s Tenth and Tokyo Girl). His latest book, Sea Trial, was a 2019 Governor General’s Award finalist for nonfiction and an Independent Publishers Book Awards medalist in the memoir category. See here for a review of Sea Trial by Theo Dombrowski in The Ormsby Review no. 503 (April 22 2019). Brian lives in Nanaimo.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#849 The BC coast by wooden boat”