#836 Yucho Chow’s wide & diverse lens

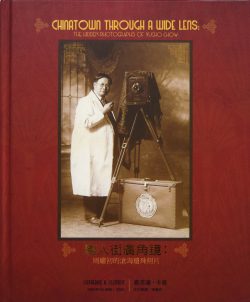

Chinatown Through a Wide Lens: The Hidden Photographs of Yucho Chow

by Catherine B. Clement, translated by Winnie L. Cheung

Vancouver: Chinese Canadian Historical Society of British Columbia, 2020

$70.00 / 9780993659331

Reviewed by May Q. Wong

*

Chinatown’s photographer was not just for Chinese.

Chinatown’s photographer was not just for Chinese.

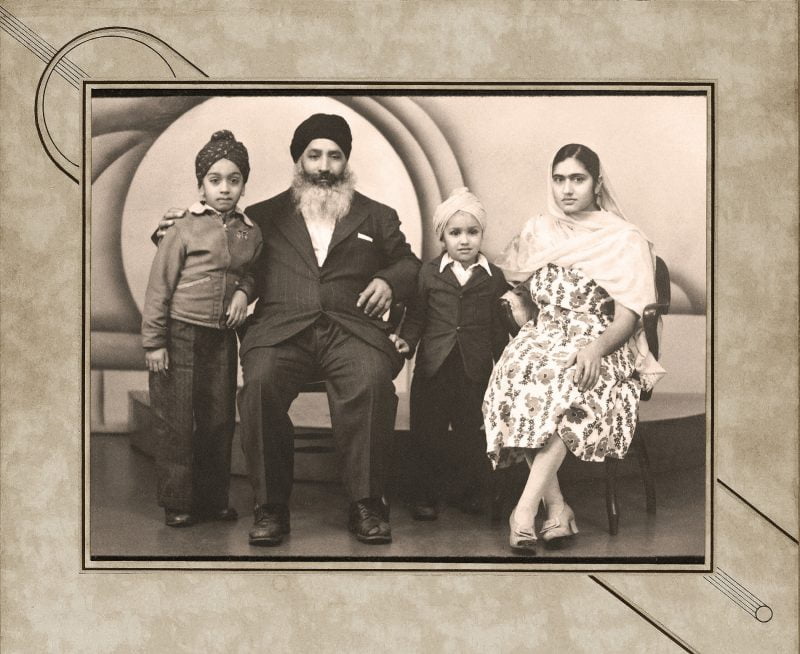

This substantial coffee-table book of photographs tells not one, but over 200 stories in tantalizing, bite-sized vignettes. Although presented in English and Chinese, Yucho Chow’s wider lens focused not just on the Chinese who frequented this popular studio in Vancouver’s Chinatown, but also First Nations customers and immigrants from South Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe.

These rediscovered stories remind us that during the first half of the 1900s, British Columbia was not a welcoming place for non-whites, or for people whose first language was not English. Yucho Chow provided an affordable service that was accessible to anyone, “no matter their skin colour, language, religion, or socioeconomic status” (p. 25). He welcomed customers who were turned away from white-owned businesses, throughout a forty-year period that saw race riots, legislated discrimination, two World Wars, and the Great Depression.

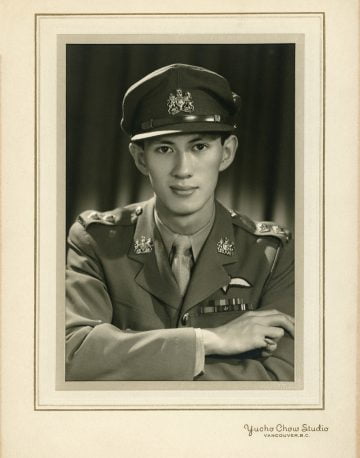

Catherine B. Clement was collecting interviews for the Chinese-Canadian Military Museum in Vancouver as a volunteer curator (for which she received the Sovereign’s Medal for Volunteers in 2016), when she could not help but notice Yucho Chow’s distinctive word marks on many of the studio photographs in the family albums of those Second World War veterans. After eight years of research, Clement had identified 200 photographs that she curated for a 2019 exhibition in Vancouver’s Chinatown. Because of that show, over 200 more photos from Yucho Chow’s studio were brought to light, previously hidden “in hundreds of dusty boxes and ageing family albums or buried in the files of private memorabilia collectors” (p. 9). Chinatown Through a Wide Lens: The Hidden Photographs of Yucho Chow is a curated selection from that precious collection.

Owing to the fact that so little is known about Yucho Chow’s personal life, this book is less about “Vancouver’s first and most prolific Chinese photographer” (p. 9), and more a tribute to the important photographic legacy that he left through his life’s work of over four decades, and which was continued by his sons. Clement summarized his life in a few brief paragraphs and we can only make assumptions about the man through his business practices.

Yucho Chow arrived in Vancouver from China in 1902. This was the year that the Canadian government doubled the Chinese head tax from $50 to $100. Only a year later, it would be raised to $500, an amount that could have bought a comfortable house at the time.

The head tax was meant to discourage Chinese immigration, first imposed after the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which the Chinese were integral in building. Yucho Chow was ready to pay the price of admission to make a better life for himself and his family. Within five years of his arrival, he opened his first photography studio and within a decade, was successful enough to pay $500 each for his wife and daughter to join him in Canada.

He ran a family business. Eldest daughter Mabel served as his assistant in all areas of the business, as well as acting as his “muse, posing for countless photos as he honed his skills in the early years” (p. 38). Later, his Canadian-born daughter, Jessie, painted the photos so skilfully in oils that they looked “as if they were originally shot on colour film” (p. 41); the portrait of Rosina (Agostino) Alvaro (pp. 58-59) being a prime example. Sons Peter and Philip learned the craft and eventually took over the business after Yucho Chow’s sudden death on November 16, 1949, and would run it until 1986.

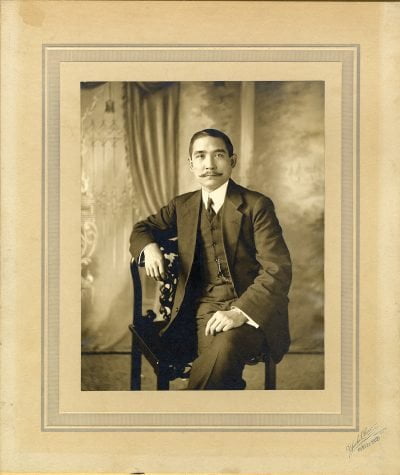

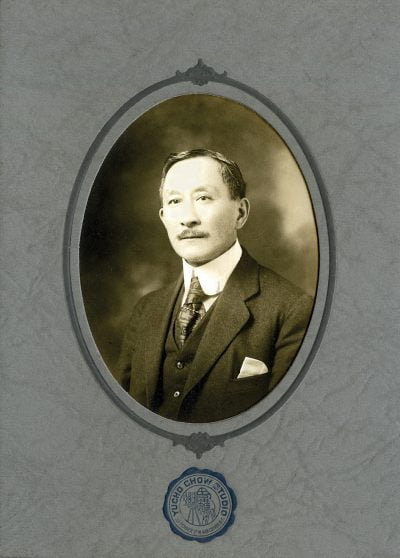

Portraits of Yucho Chow show a confident man. As a young man (p. 27), he sports a trimmed moustache while wearing a crisp Chinese-style garment; while in another (p. 46), perhaps in his later middle years, he wears a well-filled (at the time, looking portly was a sign of success) three-piece suit and is lounging with a lit cigar between his fingers. In both pictures, a pocket-watch chain dangles across his chest.

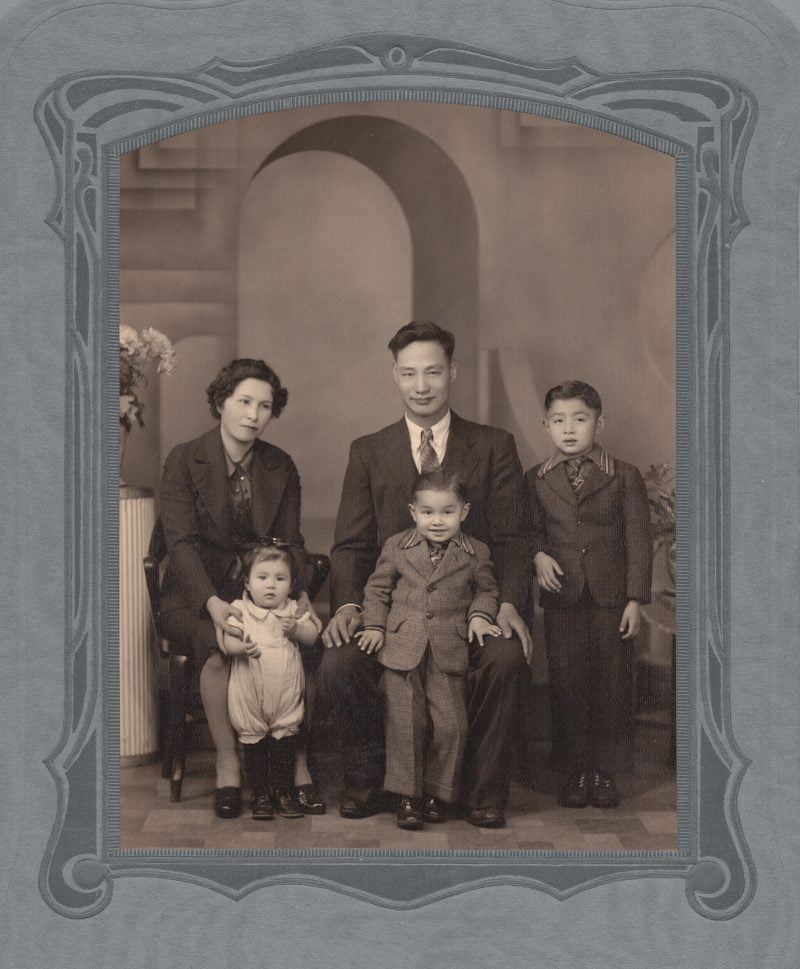

Having a photograph taken during the first half of the twentieth century was a special occasion, so different than our current “selfie” culture. It usually meant saving money for the photographer’s fee, wearing one’s best clothes, taking the time to go to a studio, posing (perhaps using props to signify the occasion), and waiting for the prints to be developed, as Clement notes:

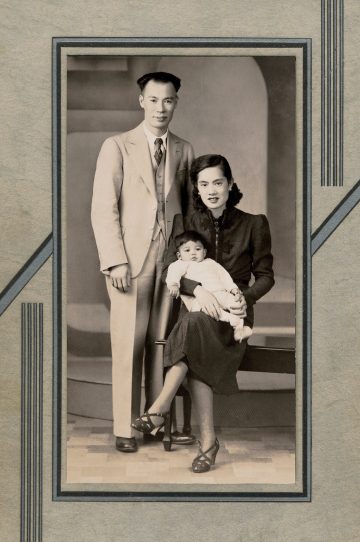

Photographs allowed people to share a story about themselves and were intended to project an image of success and show the relatives back home that the cost and sacrifice of emigrating had been worth it. Most often, photographs commemorated important milestones and special moments (weddings, birthdays, anniversaries, etc.) or marked the arrival of a new generation born in the adopted homeland (p. 30).

The Chinese Immigration Act (1923) virtually closed the doors to further immigration from China. This type of legislated discrimination, including the denial of the right to vote and to practice certain professions — even against those born in Canada — continued until 1947. An example is Won Alexander Cumyow (1861-1955, pp. 88-89), the first Chinese-Canadian born in Canada. He studied law, but because of his race was barred from practicing. He was a court interpreter for Judge Matthew Begbie and became a community leader.

First Nations peoples have suffered and lost much as a result of colonization. But sometimes, people find connection in unlikely places. A photo of the Grant Family (pp. 222-223) shows Agnes Grant, of the Musqueam Indian Band, her husband Hong Tim Hing, from Zhongsan, China, and three of their children (Helen, Larry, and Gordon). A recent documentary about the family, All Our Father’s Relations, tells of the shared histories between many Indigenous and early Chinese people.

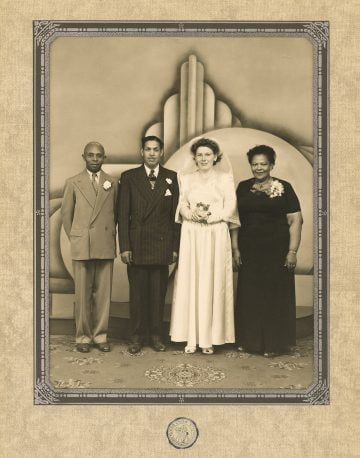

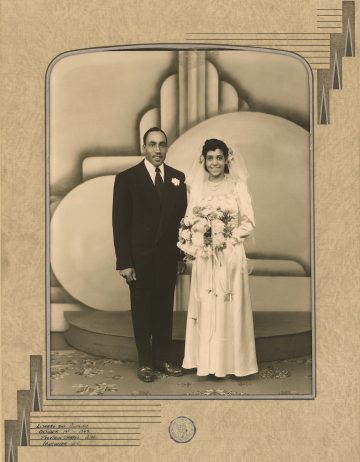

The “Unnamed Couple” (pp. 136-137) shows the wedding of another mix-raced couple — a White bride and a Black groom. Taken around 1942-1950, this event would have been a rarity. A number of the photographs in this collection have yet to be identified, so this is another incentive to look through and perhaps find someone you might know, and solve a mystery!

Leonard and Adeline Lane (pp. 124-125) were actively involved in fighting for civil rights as members of the British Columbia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People. Mr. Lane was a founding member of the BC branch of the Unity Credit Union, which loaned money to members of the Black community of Strathcona.

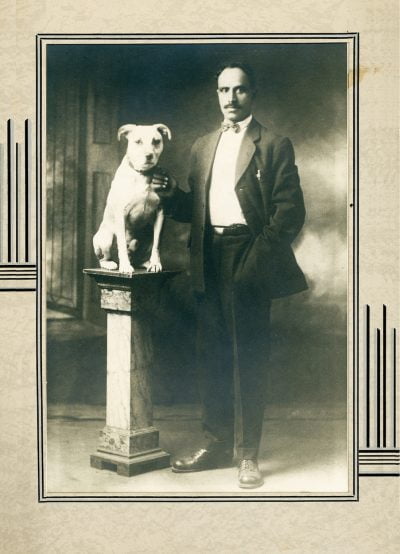

Some of the first immigrants from India to British Columbia were Sikhs. As many were former members of the British Army, they were at first respected. But as more came to settle and work, attitudes became more hostile, culminating in the Komagata Maru incident of 1914, when Canadian authorities turned away a shipload of mostly Sikh refugees, all of whom were British subjects. Ishar Singh Gill, shown here with his attentive dog King (pp. 54-55) arrived in 1906 and had this photograph taken around 1918. Although he was a successful businessman, on local government documents, he was referred to as faceless “Hindo #10.”

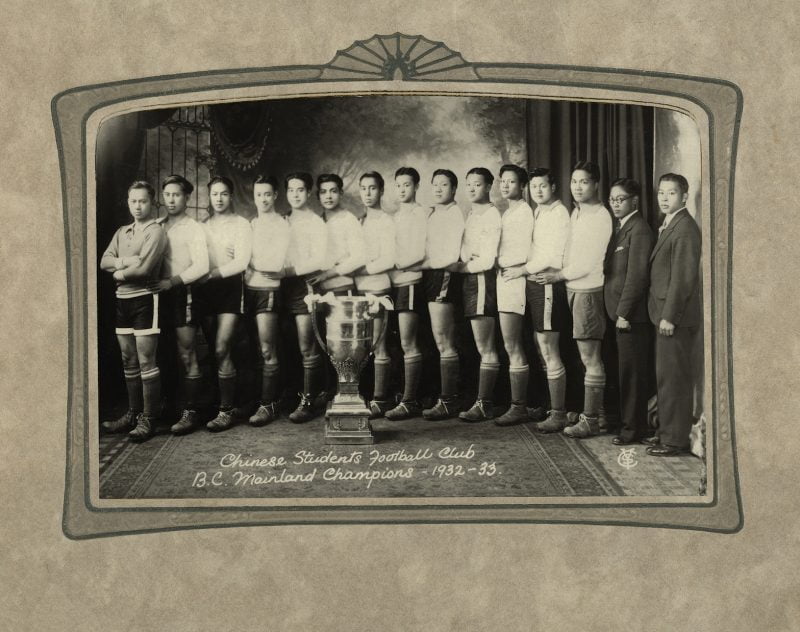

In addition to weddings, Yucho Chow recorded other events worth celebrating. The Chinese Students’ Football Club (pp. 118-119) was the only non-white team in British Columbia, and the soccer field was the only place the Chinese could compete as equals. When it won the prestigious B.C. Mainland Cup in 1933, against a formidable team from UBC, all of Chinatown celebrated. The team was inducted into the British Columbia Sport Hall of Fame in 2011.

One of Yucho Chow’s slogans was “Rain or Shine. Anything. Anywhere. Anytime” (p. 33). In the early years, he made himself and his studio available, 24/7. He was known to haul his equipment to different locations to record people, places, and events. He had photographed the Russian Youth Orchestra (pp. 210-211) in 1939, and would have been aware of the local community’s ties back to Russia.

A 1942 photo, Aid for Russian Refugees (pp. 316-317), shows a long-bed truck loaded with crates of “clothes, shoes, medicines, and food” destined for the USSR, and the volunteers who collected them.

Yucho Chow also photographed a world leader (Dr. Sun Yat-Sen), a future judge (Wally Oppal), the father of another future judge (Randall Wong), a future author (Wayson Choy), and a war hero (Douglas Jung was a decorated Second World War hero as well as Canada’s first Chinese Member of Parliament).

This beautiful book is a marvellous record of the cultural diversity of early Vancouver. Unfortunately, this collection represents only a minuscule portion of Yucho Chow Studio’s work. When the studio doors were finally closed in 1986 by his sons Peter and Phillip, they were faced with the dilemma of the ownership of thousands of negatives, and in the end, decided to discard them.

Yucho Chow’s photographs have been cherished and handed down through the generations. What might be hiding in your family’s old photograph albums?

*

May Q. Wong researches and chronicles the extraordinary in ordinary people. She is a graduate of McGill University and holds a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Victoria. May started writing for publication after retiring from the BC Public Service in 2004. A Cowherd in Paradise: From China to Canada (Brindle & Glass, 2012), offers a glimpse into the lives of a couple separated for 25 years of their 50 year marriage, and the impact of Canada’s discriminatory laws on their family. City in Colour: Rediscovered Stories of Victoria’s Multicultural Past (TouchWood, 2018) (reviewed by Tom Koppel in The Ormsby Review, no. 513, April 2, 2019) is a timely reminder of the importance of a diverse range of immigrants and their contributions to our community. In addition to reading, writing, and speaking to groups about her books, May creates useful and beautiful things with knitting and sewing needles – the latest being hand-beaded facemasks. She and her husband are working towards earning their 3rd degree Black Belt in Kenpo Karate, thus maintaining a balance between the development of mind, body, and spirit.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

12 comments on “#836 Yucho Chow’s wide & diverse lens”

My father and mother-in-law came from Punjab in the 30s and we have a few photographs taken at the Yucho Chow studio. I would like to contact Catherine Clement to pass them on to her.

Thanks, Donald. I have your email address and will introduce you to Catherine by email. I’m sure she will be most interested in your photos. Very best, Richard

Where to find a signed first printing?

Hi Kim, try contacting the Chinese Canadian Historical Society of British Columbia, Chinatown House, 188 E Pender St, Vancouver, BC V6A 1T3. Their email address is info@cchsbc.ca I hope this helps! Best wishes, Richard

Terrific review of Catherine’s wonderful book that also included some of my relatives. Thank you for all your work in putting it together.

Wow! Such incredible work by Catherine Clement and a good well-deserved review.

A great book review! All the accolades go to Catherine Clements for her 10+ years of research. A picture indeed is worth a thousand words. As a grandson to Yucho we give healthful thanks to Catherine.

Wonderful review. My mother Jessie was the daughter mentioned in the review, however, the name is spelled incorrectly. Please revise if possible.

Thank you.

Thanks, Carol! I have corrected the name, from Jesie to Jessie.