#834 Lessons from my brother’s room

The Guilt Factor: A personal exploration with assistance from Antigone

by Al Jones

*

Experiencing and living with guilt, whether small or big, is part of the human experience, and as I look back on my life I ask myself how guilt has affected me. At times, I am perplexed by how guilt can be both good and bad.

*

I was nine years old, gangly, and the baby in the family. Our family, five of us, lived in a modest bungalow, one that veterans could own through a generous allowance from the federal government after the Second World War. There were many homes like it on our street in South Vancouver. We were poor. My father had contracted tuberculosis from his efforts in a tank crew during the war and spent many years in the hospital in a remote city many kilometres from us.

My much older brother, a hard-boiled tough guy who would find his way in the world through hard work and natural intelligence, had some money. He was not careless with it, because he did not have much. He did shift work, which meant his sleeping patterns were irregular.

One day while he slept, I decided to investigate his room. I believe that at my age many of my activities were driven by a passionate curiosity. I chose to explore, so I crawled on my hands and knees into his room. It was dark, but not so dark that I could not see. He was sound asleep in a slumber that was not easily broken. The room was orderly with smells of sweat and dirt. His well-worn jeans lay over the back of a chair.

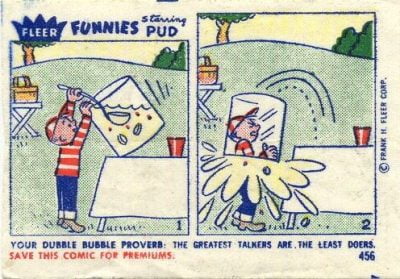

The pockets of my brother’s jeans reached, upside down, to the yellow linoleum floor. Beckoning me were two coins, a nickel and a dime, real money in those days. The sweet sticky taste of Dubble Bubble gum began to haunt my not so innocent taste buds. I briefly tried to reason why I should not convert the coins into something I really wanted. But reasoning did not last. Dubble Bubble was so sweet and juicy that I was sure I could taste it as I stared longingly at those coins.

I picked them up and in a heated passion dashed to the sweet offerings of the local corner store. I was accompanied by a strange haunting feeling that maybe I had done something wrong. I held the coins for dear life. I paused with my goal in sight, on a lane filled with loose rocks. The coins slipped from my sweaty hands. Crushed, I tore those rocks apart, but to no avail. The coins were gone. Was God punishing my evil deed? Now I began to experience a much different passion – worry and guilt that my brother might find the coins missing.

I picked them up and in a heated passion dashed to the sweet offerings of the local corner store. I was accompanied by a strange haunting feeling that maybe I had done something wrong. I held the coins for dear life. I paused with my goal in sight, on a lane filled with loose rocks. The coins slipped from my sweaty hands. Crushed, I tore those rocks apart, but to no avail. The coins were gone. Was God punishing my evil deed? Now I began to experience a much different passion – worry and guilt that my brother might find the coins missing.

I slunk back home dejected and in tears. My mother cornered me with, “Your brother is missing some coins that fell on the floor in his bedroom. Do you know anything about it?” The excuses I composed sounded reasonable, “They were just there on the floor. I didn’t think anyone owned them.” Guilty.

I slunk back home dejected and in tears. My mother cornered me with, “Your brother is missing some coins that fell on the floor in his bedroom. Do you know anything about it?” The excuses I composed sounded reasonable, “They were just there on the floor. I didn’t think anyone owned them.” Guilty.

My guilt about this covert act of theft is deeply embedded within me. My experience as a nine-year-thief, while trivial in its unfolding, left a powerful life lesson about honesty and stealing. A good thing about guilt is that it can reduce the risk of repeating our mistakes.

Another is that such accumulated experiences of guilt can provide society with a collective code of conduct and ethical understanding. The expectation of good behaviour can enhance community building. Guilt can be helpful.

Another is that such accumulated experiences of guilt can provide society with a collective code of conduct and ethical understanding. The expectation of good behaviour can enhance community building. Guilt can be helpful.

There is no universal template to our responses to guilt. That mental pain is often not good, and it prompts a variety of responses. All feelings about guilt include some form of mental pain for an individual and at times societies. We cannot “see” guilt, but we can sometimes see the consequences, as do most of the characters in Sophocles’ play Antigone.

*

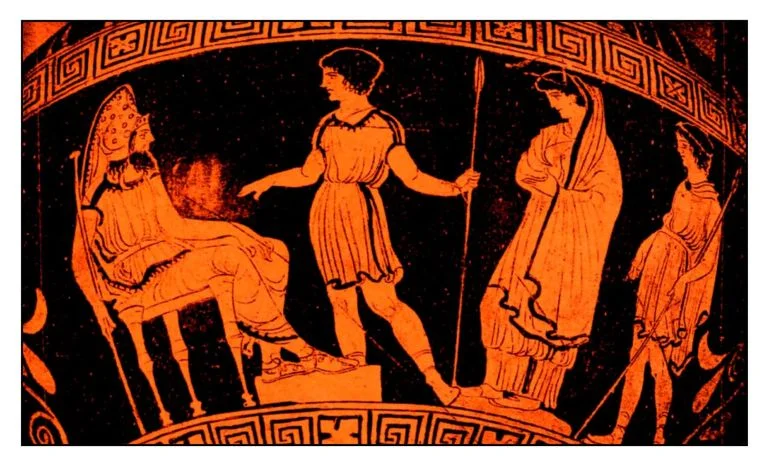

As part of my ongoing studies at Simon Fraser University in the Graduate Liberal Studies program, I had the chance to read and reflect on Antigone, written around 442 B.C. Antigone, daughter of Oedipus, was sentenced to death by King Kreon, who forbade anyone to mourn or bury Antigone’s brother Polynices, who had led a civil war against Thebes. Kreon decreed that Polynices should remain on the battlefield outside of Thebes to be scavenged by dogs and vultures. Unable to face the looming guilt and shame of leaving her brother’s soul in anguish, and unwilling to betray the requirements of divine law for a proper burial, Antigone crept onto the battlefield to give Polynices a respectable burial.

Apprehended, Antigone committed suicide by hanging before her death sentence could be carried out. Kreon’s decree then led to the suicide of his son Haemon, who was in love with Antigone; and then to the suicide of Kreon’s wife, Eurydice, in grief at the death of her son Haemon.

In the play, Kreon laments to the leader of the chorus, Koryphaios:

KREON: Mindless, hard, deadly crime!

Look: the killer and kill, a father and son.

Poor and worthless counsel, my own.

My boy, young,

And death come soon.

Gone, gone!

I was wrong, not you.[1]

By causing Antigone’s death, Kreon loses his household. His proud passion to uphold the laws of the state over divine law, and over Antigone’s human reason, led to the death of his own son and wife. Crushed by the weight of guilt, Kreon laments, “Take me away, a poor fool. I killed you both, son and wife. No, nowhere to look…. It leaps on me, it crushes. Messenger and servants lead him out slowly, to the right.”

Our wounds from guilt can be carried with few visible signs of anguish or they can erupt into calamity.

*

While it might seem a big leap from trivial stealing as a boy to my own career in business, there was sometimes a label attributed to me that I did not like. Many years later, in my role as the Human Resources Director of a large organization, I discovered that I’d been given the label Dr Death, a moniker that made me feel both regret and shame as it broke one of the rules that I, and many people, live by: “Being nice to others.” At its most basic this means that we show them respect.

While it might seem a big leap from trivial stealing as a boy to my own career in business, there was sometimes a label attributed to me that I did not like. Many years later, in my role as the Human Resources Director of a large organization, I discovered that I’d been given the label Dr Death, a moniker that made me feel both regret and shame as it broke one of the rules that I, and many people, live by: “Being nice to others.” At its most basic this means that we show them respect.

Dismissing people was part of my job, but I was rather shattered by the Dr Death crown. At such times, I constructed reasoned intellectual and emotional walls around myself for protection. No one would see my walls but me. The key rule for the construction of those walls was not to get too close to anyone. I felt guilty about those walls, but they allowed me to cope with trying times, especially when I needed to release someone from the organization that employed me. This guilt caused me turmoil and may have contributed to my departure from the business where I acquired that label. In a strange twist, my guilt provided a way to protect myself.

*

I cannot match the calamities of Antigone or the pain and guilt of King Kreon, but the anguish, pain, fear, and loneliness I felt after my wife Linda died in 2009 from lung cancer was life changing. People are perplexed when I tell them that I carry guilt even though there are few, if any, visible signs, of it. How could I have carried forward guilt from this experience?

Linda did not smoke, ate organic foods, was a highly respected professional in her work, and was much loved by family and friends. From the time of diagnosis in June 2006, and particularly 24-7 for the last six months of her life, my role was to support and care for her. I still struggle with guilt for the level of support I provided her. Did I do enough? Could I have done more? What mistakes did I make that contributed to her illness and death?

One thing is clear to me: while time does not heal all wounds, it does soften them. Linda’s illness when diagnosed at UBC hospital as stage four cancer, primary site unknown. Immediately time stood still. Time was obliterated. There was no future, only an intense and dreadful present. The day of diagnosis is embedded in me with crystal clarity as is the final day of her death. All the other days are a hazy recollection of time with medical staff and countless hospital visits. The long process of acquiring and living with my guilt stretches back almost 13 years.

My guilt preceded that dreadful first day of diagnosis by many years. Linda and I had a healthy relationship and were very proud of our two sons. In 2000 I chose to leave corporate life in order to start my own consulting practice. For the following six years my practice did not generate the level of income I had provided in the past. Nowhere near it. It became a source of tension between us. At times Linda confronted me with my decision and suggested that I take an additional job of some kind. She continued to work full-time in a stressful job. I refused to take just any job. Did this spark an unrest inside Linda that ultimately led to her death? Did my initial reasoned responses to her requests, which would turn to passionate denials, fuel a deep pain that at some molecular level disrupted her DNA such that a growth emerged in a tiny pocket somewhere, that patiently grew into a killing inferno?

Whatever its causes, that killing inferno led to Linda’s death. I cannot recall when I began to shift my thinking from, “did I do enough?” to thinking and feeling, “I do my share.” Was that before, during, or after her illness? I do know that my guilt about feeling inadequate became twisted to the point, many years after her death, that “I do my share” became a mantra that would drive me to do so much that I would become completely exhausted.

Is my lessened guilt over the years and my increased awareness of its causes a good thing? Probably. Has my guilt taught me a lesson? Absolutely. I am still stuck with unanswered questions from the time of diagnosis until Linda’s death. Did my actions lead to her choosing not to communicate openly about her illness and the future? I can never know the answers to these questions. This unknown is an enigma that cannot be reconciled because, as King Kreon proclaimed in his introductory monologue, “It is impossible to know a man’s soul, both the wit and will, before he writes the laws and enforces them.” Kreon refers to the casting of laws into written form. His comment applies equally to my verbal, not written, contact with Linda, and makes me wonder if I should have pressed harder for some discussion about our relationship, our properties, our life. Linda’s only requests were “that I not marry a gold-digger and that I need to look after our sons.”

The first request is clear, the second is open. What does “look after our sons,” who are now adults, look like? Need I live the life of a hermit and bequeath everything to them? Should I not enjoy life in the manner that Linda and I did, through travel and adventure? I have yet to resolve fully how to look after our sons. Without clearer wishes the only person who can answer that question is me. But the Messenger in Antigone gives me a powerful suggestion about how to deal with the quandary: “Kreon has shown that there is no greater evil than men’s failure to consult and consider.” Given this timely passage, it is up to me and to those who I trust, to consult and consider what might be a fair and reasonable way to approach the meaning of “Looking after our sons.” This action will help to reduce my guilt about what to do.

The first request is clear, the second is open. What does “look after our sons,” who are now adults, look like? Need I live the life of a hermit and bequeath everything to them? Should I not enjoy life in the manner that Linda and I did, through travel and adventure? I have yet to resolve fully how to look after our sons. Without clearer wishes the only person who can answer that question is me. But the Messenger in Antigone gives me a powerful suggestion about how to deal with the quandary: “Kreon has shown that there is no greater evil than men’s failure to consult and consider.” Given this timely passage, it is up to me and to those who I trust, to consult and consider what might be a fair and reasonable way to approach the meaning of “Looking after our sons.” This action will help to reduce my guilt about what to do.

*

I have loaded my selection of guilt songs throughout my life and have put them in storage for retrieval. My context triggers songs about my brother’s coins, my Dr Death moniker, and Linda’s untimely passing — even though I may not recall the literal words or even the tune. But being triggered is only part of my story. Judging guilt as good or bad can only be done through the lens that I hold up to myself.

*

Al (Alan) Jones writes: It’s a privilege to have been born and to still live in Vancouver. I have been married for 35 plus years altogether and have two wonderful grown sons, aged 34 and 32. My wife, Linda Bolding-Jones, died from cancer over eleven years ago. I took a lead role for ten years to raise money for organizations supporting people living with and dying from cancer. I have learned that loss never goes away, but I am in a second loving relationship that has taught me that love can be possible, expansive, and surprising. Education was a challenge for me. I graduated from SFU, and then from BCIT at the top of my technology program, and I also taught part-time in the Beedie Business School at SFU. My business career in Human Resources included working for local technology companies and large globally-based organizations. Travelling the world was expansive for me. For the last 20 years I ran my own consulting practice called Human Capital. My business career has now faded as I focus on a Master of Liberal Studies at SFU. I wrote this essay in September 2019 for Sasha Colby’s introductory GLS 800 course. I thank Dr. Colby for giving me the freedom to express myself in a supportive environment.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Sophocles, Antigone, translated by Richard Emil Braun (Oxford University Press, 1973).

2 comments on “#834 Lessons from my brother’s room”

YOU OWE ME 15 CENTS PLUS INTEREST, OR WE CAN SETTLE ON SOME DUBBLE BUBBLE GUM!!