#823 Canadian internment legacies

Civilian Internment in Canada: Histories & Legacies

by Rhonda L. Hinther and Jim Mochoruk (editors)

Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2020

$31.95 / 9780887558450

*

The Stories Were Not Told: Canada’s First World War Internment Camps

by Sandra Semchuk

Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2019

$34.99 / 9781772123784

*

Harry Livingstone’s Forgotten Men: Canadians and the Chinese Labour Corps in the First World War

by Dan Black

Toronto: James Lorimer, 2019

$27.95 / 9781459414327

All books reviewed by Keith Regular

*

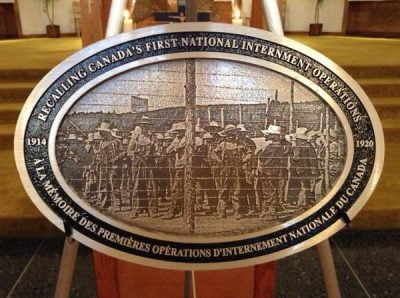

Twice in the 20th Century Canada mobilized for total war and using emergency powers granted by the War Measures Act determined to deal with anticipated threats from without and within. Citizens, immigrants and refugees alike were declared enemy aliens and believed a national threat. All were subjected to various forms of repression including removal or internment or both. The consequences for those caught up in the state’s machinations were often personally and financially dire.

Canada’s regrettable selective internment policy, especially that of Ukrainians during World War I and Japanese Canadians during World War II, has stimulated a publishing frenzy that shows no signs of abating. Internment was an oppressive othering “us” and “them” binary, often extreme when applied to those culturally and racially different. It was and remains a controversy; we in this generation habitually impose current values on the past in a well-meant quest to redress past wrongs. There is, however, less than unanimous consensus on injuries that span personal, communal, provincial and national boundaries, and that occasions both grief and angst as documented by historians and recalled by participants and descendants.

This review considers three works considered as explorations into internment; a collection of essays edited by Rhonda L. Hinther and Jim Mochoruk, Civilian Internment In Canada: Histories & Legacies, Sandra Semchuk’s The Stories Were Not Told: Canada’s First World War Internment Camps, and Dan Black’s Harry Livingstone’s Forgotten Men: Canadians and the Chinese Labour Corps in the First World War. Pointedly, all three question Canada’s commitment to democratic principles and civil rights in time of crisis and find it wanting, and intended or not, legitimate agitation for redress for perceived past wrongs.

Civilian Internment In Canada gathers together twenty essays and personal views organized in nine themes. Readers are challenged to reconsider internment’s significance and to accept that it embraces a variety of cultural, ethnic, political groups and individuals and the differing manner with which they were dealt. Rhonda Hinther and Jim Mochoruk anchor this discussion by proposing that internment constitutes evidence of Canada’s “rich and shameful record of violating civil rights and liberties” using the war emergency as an excuse to do so (p. 1). The contributions found here, however, do not unanimously subscribe to this critique. Dennis Edney posits that internment as human rights history foreshadows current crisis reality and, as in the past, produces “ill-conceived” state responses. Edney admits that democracies often successfully meet such challenges. In this collection, however, victims loom large.

Kassandra Luciuk argues that the almost singular focus on “redress-inspired scholarship,” and the 40,000 interned Ukrainians during the First World War, distracts attention from Ukrainians as members of the radical left engaged in worker militancy (p. 50). The conclusion that internment was how Canada “generally” and “traditionally” dealt with undesirables seems a stretch. The internment of radical Ukrainians in the context of total war and an environment fearful of Bolshevism may, for some, legitimate the state’s harsh response.

Essays by Myron Momryk, Jim Mochoruk, Rhonda Hinther, and Marinel Mandres stress the significance of context in internment politics and reveal that despite its intentions, the state was not always effective in its repressive measures. Momryk discusses how the internment of members of the Ukrainian Farmer Labour Temple Association and an individual, Peter Prokopchak, during World War II, were influenced by national and international responses to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939. Jim Mochoruk posits that harassment of the left during World War II, based on ethnicity and politics, and especially of the People’s Co-operative of Winnipeg, reflects the fragile standing of civil liberties in times of real or perceived crises. Yet Mochoruk, in invoking the military terminology “collateral damage” to describe the impact of government policy during a time of perceived crisis, may blunt his argument that the treatment meted out was absolutely unjustified.

Similarly, Rhonda Hinther notes that in the case of Gladys MacDonald, the only leftist woman to be interned during World War II, the state neglected to energetically repress leftist women who, in some cases, exceeded men in both their leftist behaviour and dedication. Marinel Mandres discovered that state repression was not always effective, and that Serbians benefited from diplomatic intervention. These essays offer a counter narrative to the generally accepted view that objects of state oppression were overwhelmed in a tsunami of ruinous repression. For example, the distinction between “enemy alien” and “friendly alien,” based on nationality or citizenship and not ethnicity, is made here.

Investigating the treatment of Italian Fascists in Canada during World War II, Travis Tomchuk reveals that government officials resorted to an abusive system of informants who implicated members of their own community in a bid to settle personal scores. Italians, however, also received redress, in this case when a judge, for want of evidence of subversion, ordered the release of the arrested. Of the 600 Italians interned, only a minority were declared fascists. This topic is ripe for further inquiry.

Christine Whitehouse’s multi layered essay on gender identity among internees, specifically young Jewish non-citizen men, is notable. The lack of privacy and of women generally in internment camps challenged gender identity and revealed the malleability of sexuality when some men lapsed temporarily into homosexuality. However, Whitehouse’s observation that the state ignored sexual behaviour behind closed doors is somewhat offset by the behaviour of camp guards who demanded the “gifting” of sexual favour and sometimes committed rape. Whitehouse also reveals that tension between the reality of a modern and empowered woman and declining patriarchal power led to the eroticization of females and of the female form. Her findings certainly invite broader research to provide more nuanced views on a little known topic.

Several essays challenge the impression that internment victims passively accepted their fates. Aya Fujiwara argues that Japanese Canadians removed to communities in the BC interior and Prairie provinces, where their movements were restricted and where they were placed under RCMP surveillance and subjected to exploitive labour, experienced an alternate form of internment. Fujiwara argues that these Japanese successfully effected their integration into the regional economy, a finding that challenges the belief that they passively accepted their circumstances. Similarly, Mikhail Biorge cites a campaign of “remarkable pushback” through “strikes, protests, riots, and mass non-compliance” involving men, women, and children (p. 180). More attention to the agency of all groups subjected to the various guises of internment proposed in this collection may provide a much-needed corrective to both scholarly dialogue and popular views.

Grace Thomson (née Eiko Nishikihama) uses personal recall and some of her mother’s memories, the latter completed later in life, to offer insight into the impact of internment on one family. She laments the forced migration from the BC coast, the internment in the interior of BC, the denial of civil rights, and the confiscation of property. The personal tragedy of the assault on cultural identity through the loss of family photos and possessions is palpable and continues to affect her. Given the uncertainty of memory, however, the use of her own and her mother’s recall also merits caution.

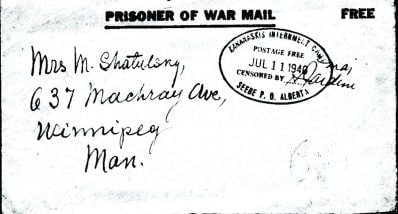

Clemence Schultze, born in 1950, recounts the experience of her father Rolf, a German political refugee, interned in Canada (1940-41), and her mother Dorothy Caine, an Anglo whom Rolf met in England. Schultze rightly warns that her analysis, taken mostly from her parents’ letters, is tentative. “One was merely told, only later recognizing how ritualized was the telling and how censored the content” (p. 231). Censored material provides real challenges to discerning the temporal reality of the Schultzes’ experience.

Several contributions consider the challenges that museum settings bring to communicating the past. Jodi Giesbrecht recognizes the tension between a necessary dearth of written words and visual presentation in museums, leaving much in the way of interpretation and meaning to the viewer/reader. Griesbrecht believes, however, that museum exhibits add nuance, validate experiences, and reflect diversity in historical human rights issues.

Next up are Ed and Tod Caissie, who admit that a museum focus on “negative cultural heritage” sites, such as internment Camp B-70 in New Brunswick, resists the accurate definition of “contested memories . . . in a balanced manner.” Notably, a wall mural that is intended to communicate repression loses some of its impact by depicting relaxed and perhaps bored camp inmates through a foreground of barbed wire (p. 269). Personal artifacts also indicate a creative energy that seems incongruent in a repressive regime.

Emily Cuggy and Kathleen Ogilvie continue the theme of “contentious topics” by declaring boldly that an individual’s “story” becomes community and national history. They employ a violin crafted during internment (p. 291) to betray the illusion, or perhaps delusion, that historically Canada welcomed diversity. Besides exploring the meaning of the violin as an artifact, Cuggy and Ogilvie argue that the instrument serves the politics of redress. However, the violin appearing as if viewed through barbed wire in a lighted display questions its neutrality in communicating an unbiased corrective to a disputed history.

Sharon Reilly trusts museums to provide a “richer exhibition experience” in understanding the impact of war on Japanese Canadians. Museums face unique and sometime formidable challenges in communicating the past. Challenges, however, loom large in her analysis. By way of illustration, a photo showing Japanese Canadians on a sugar beet farm (p. 300), does not necessarily depict, as the author asserts, young children and advanced elderly being required to do “heavy manual labour.” Similarly, the photo on p. 301 does not, strictly speaking, show rudimentary “tarpaper shacks.” The constructions depicted are clearly boarded and are much more substantial and, by implication, provided the inhabitants with better shelter than Reilly intended to communicate. Though otherwise solid, Reilly’s essay is not the best fit for Civilian Internment in Canada because its broader view diminishes the collection’s focus on internment.

Judith Kestler details the experiences of German merchant seamen, another group “hosted” by Canada. These mariners were servants of the Nazi state. Many had been indoctrinated into Nazi ideology and were members of the German Naval Reserve. Kestler sees no reason for a lament, as of all internees merchant seamen could perhaps be considered the most justly interned; yet their treatment was balanced and, for some, internment was a positive experience, a perception that points to the need for further research on this group.

Paula Draper’s essay presents the paradox and ultimate absurdity of Jews incarcerated as Nazi sympathizers. Though German refugees transferred from England, they were regarded as POWs, perhaps a reflection that the wartime emergency distorted the ability to distinguish groups with regard to the extent of their supposed threat and the need for restraint. But as in other cases their self-advocacy, and that by others on their behalf, was not without success.

This ambitious collection concludes with two submissions on the politics of redress. Franca Iacovetta believes that the hostility with which Italian internment history is recalled and communicated has gone astray. The author makes clear that, though unfortunate, the Italian experience should not be compared with that of the Japanese, and she disputes the assertion that Italians “paid too heavy a price for their homeland passions” (p. 365). Such a stance is not to condone the impact of state behaviour on individuals or groups. Iacovetta justly reminds us, as this collection points out, that “clashing narratives” pose challenges to understanding a very complex past.

Although Art Miki, in his bookend contribution, charges that internment was a “racist national narrative,” the variety of ethnic and political groups discussed in this collection defies such a designation. No doubt racist overtones existed, but Miki’s belief that, in consequence of internment, his grandfather died a broken man constitutes a very subjective stance. His effort to encourage empathy for his family’s hurt is acceptable, but as historical evidence to elucidate extremes in state coercive power it is less tenable. That said, the prospects for drawing historical meaning from such personal introspection are potentially rewarding.

The strength of this varied collection resides in the disparate approaches to comprehending the impact of internment on individuals and groups. Readers will have to judge the merits of each approach to the service of history, being especially mindful of the caution that historians who adopt causes such as redress potentially engage in “risky business,” through clouding distinctions between “the historian’s role as public intellectual and the complex relationship between scholarly and popular versions of history” (p. 364).

The essays in Civilian Internment in Canada: Histories & Legacies convey that internment is, with the possible exception of the treatment of Japanese Canadians and Ukrainians, an unexplored and ill-defined historical labyrinth containing much potential for scholarly research and cultural study. For example, the several examples here of state “incompetence” in effecting its repression demonstrate the definite limits in the state’s ability, even in times of stress and with concentrated authority and unlimited might, to realize its intended designs. These essays bring refreshing approaches to the subject matter and a promise of dynamic future research.

Perhaps the reality of a state at total war could have been more critically considered. During the two world wars Canada censured the rights of all its citizens and restricted press freedoms. This reality necessitates critical interrogation where accusations of racism and a betrayal of democratic freedoms underpin discussions. Even if one reservedly accepts the state’s racist motivations, however, there is strength of argument in this collection. The essays, as intended, certainly add much needed nuance and refreshing approaches to internment history.

Since the publication of Ken Adachi’s The Enemy That Never Was: A History of Japanese Canadians (1976), many have adopted his sentiment and followed his lead. In the imagination, however, the “enemy” was very real — and imagination is a powerful motivating force to action. This is a dimension of the internment calling for continued investigation. The variety and strengths of the essays collected here offer much in the way of new insight on state policy and the impact of internment on individuals, political and labour organizations, and ethnic groups. These contributions successfully cast a wide gaze and will encourage continued interest in and inquiry into Canada’s complex and disputed internment history.

*

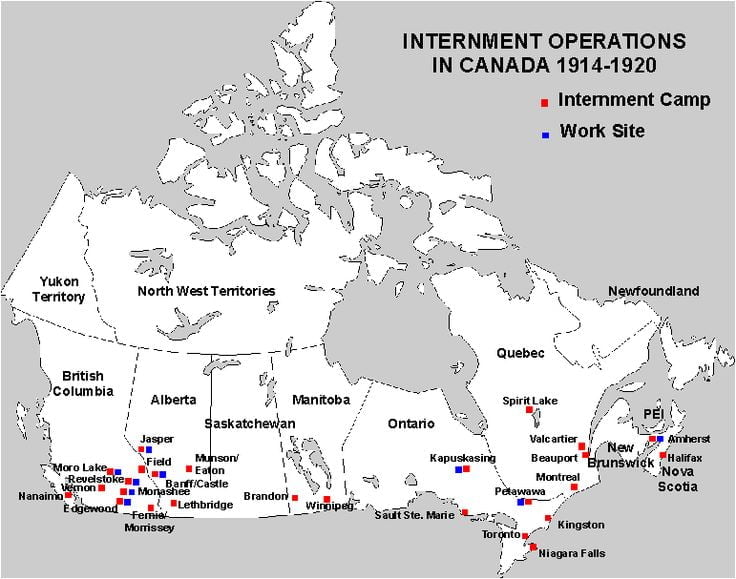

Sandra Semchuk’s The Stories Were Not Told: Canada’s First World War Internment Camps, is an outlier. The book contains an introduction, which anchors the theory; a chapter providing World War I context; a photo essay in several parts; a collection of reminisces by victims and/or descendants; and a conclusion devoted to memory and meaning. The book is a melding of Semchuk’s personal journey, visual art, narrative, and recall, all intended to highlight the ramifications of World War I internment. This is an ambitious undertaking; an endeavour to reconcile Canada’s treatment of Ukrainians with any latent sense of justice that Canadians may now express. The unfairness of internment and its debilitating impact on individuals and communities dominates, so there is little doubt that Semchuk intends The Stories Were Not Told be used to justify redress debate. A parallel purpose is to draw associations between the motivating force behind internment and the colonial-based treatment of First Nations, “whose dispossession has been the foundation for all immigration” (p. xvi) This matter is so briefly referenced, however, that it seems like something of an exaggerated attribute.

The Foreword pointedly notes that Semchuk eschewed objectivity to “compose” this work. The personal stories here both encourage reflection and burden readers with the responsibility of considering the significance of internment for individuals, families and communities.

The conundrum in internment debate has always been to reconcile the treatment of “enemy aliens” with the war emergency and determine whether or not the circumstances justified the apparent extremity of the response. The war environment caused internment, but Semchuk leaves an impression that the national emergency should be considered inconsequential to the treatment of those thought dangerous. In a bid to curry sympathy, Semchuk equates “enemy aliens” with prisoners of war. This is, unfortunately, a double-edged sword. On the one-hand it highlights the unfairness of their treatment; on the other hand it legitimizes incarceration. Clearly, in light of the war emergency the status of citizens, and of those non-citizens hosted by Canada, requires thoughtful analysis.

Semchuk details the mistreatment of internees by relating common and unwarranted abuses along with more serious incidents, such as the few escape killings, which demonstrate an egregious overreach of the application of state power. There existed practically a litany of punishments and conditions; reduced rations, straw removed from beds, warm clothing confiscated, food shortages, stolen wages, theft of personal property, etc., all in an endeavour to get internees to adhere to prescribed behaviours and adopt a prisoner mentality. Needless to say, some internees also experienced a theft of well-being that led to despair, depression, and occasional suicides.

The reality of abuse is sustained by the personal trauma related in the stories found in Chapter 3. Mary Bayrak, a child at the time, was left with the lifelong impression that she was being punished for having done something wrong. Jerry Bayrak, of the next generation, remained angry at the way his family members had been treated until the day he died.

Despite a plethora of regrettable and oppressive internment conditions, there are indications that the internees did not lack for agency, such as exhibited when one individual told a story about the camps simply because “he was told not to say it” (p. 109). Or the case of Vasyl Doskoch, who prevailed on a guard to send on his behalf a letter he had written to Ottawa critical of camp conditions. This letter may, in part, have instigated a commission of inquiry (pp. 118-120). Semchuk provides other such examples of victim resiliency.

Even though accepting limits to her “composition” for understanding the past, Semchuk argues that the “memory work” involved here legitimates her efforts. The history, she asserts, matters less than “what has happened after” (p. xxxii). Admittedly, the experiences recounted here have largely been concealed, things have been “lied” about, secrets that are “so deeply buried that they elude the conscious awareness” have been subjected to “wilful forgetting,” with but an echo of the original remaining. Semchuk’s position, however, is that a focus on “facts and details” can lead one astray (p. xxxiii). Thus, Semchuk, it appears, is engaged in an inquiry akin to folklore, where stories have the germ of truth and indicate the direction from which one has come, but approximate history only in a general sense. By requiring her readers to imagine the past she dispenses with interpreting the evidence and forswears historical certainty.

Although intended, comparisons between the state’s treatment of internees and First Nations’ experience are brief and unsatisfying. Semchuk’s assumption that similarities between the two provide a historical context for the War Measures Act is not entirely convincing. Internee confinement was more or less absolute, whereas the restrictive pass system imposed on First Nations following the 1885 Rebellion could never achieve such an ambitious goal. I do note that in her use of the pass system, in a departure from her approach otherwise, she accepts history, not “memory work.” However, the government’s efforts at rigid application of the pass system failed in the face of sustained First Nations resistance, sometimes with the tacit approval of federal agents such as the RCMP. On this point Semchuk could have benefited from recent historical scholarship.[1] First Nations, at times, employed resistance as a means to liberation.

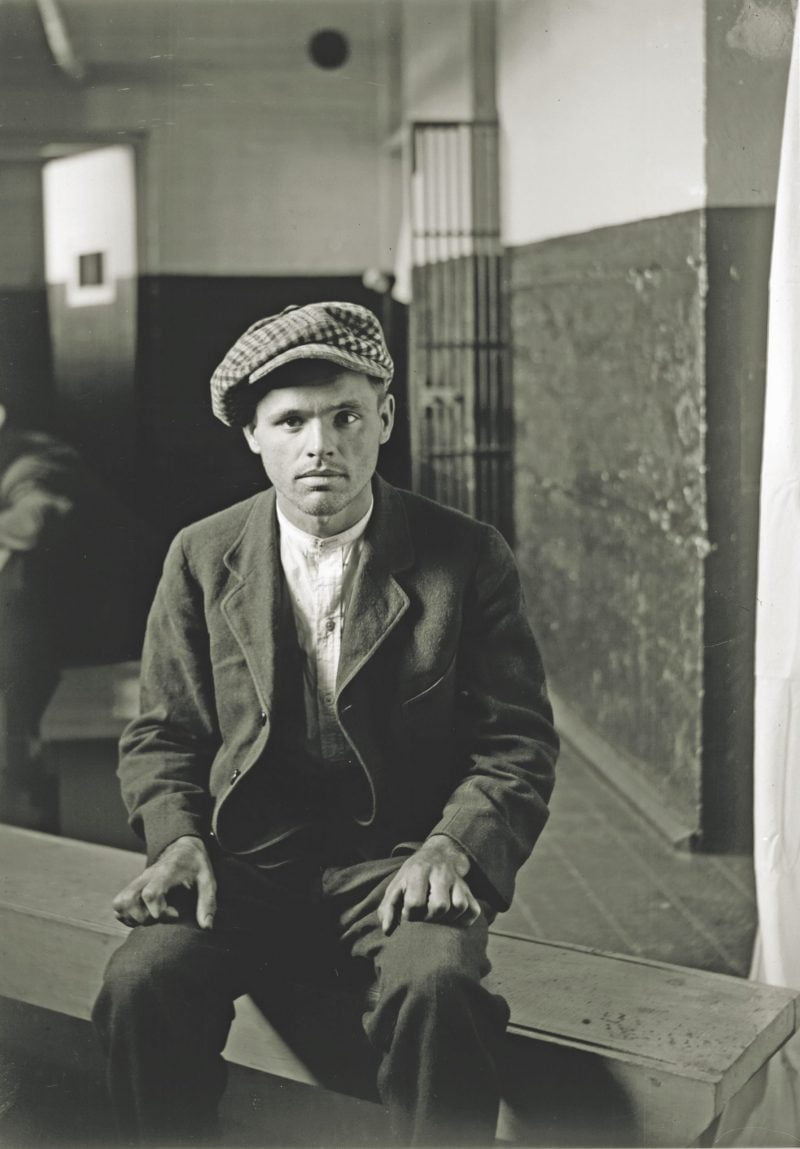

Semchuk is to be complimented for her selection of personal and archive photos. Thematic in presentation and visually appealing, they invite the observer to breach the boundaries between past and present and to appreciate the transmuting qualities of time. The archival photographs in particular are blunt reminders of a less appealing past and highlight the arbitrary capacity for malice by aggressors and the concomitant suffering by victims, especially in the case of children. Some photographs are especially moving in their poignancy (e.g. p. 47 [Kapuskasing grave markers], p. 161 [Spirit Lake women and children], and p. 194 [Michael Bahri before his execution]).

Unfortunately, the archival photographs are largely missing historical context in The Stories Were Not Told, which leaves their meaning obtuse. Thus, the observer is left to imagine, as I think Semchuk intends, the photos’ original intent. For historians there is real danger in imagining incorrectly. For example, the photo depicting internment camp internees dressed up as Indigenous people for “Indian Days” (p. xxx), is devoid of any meaningful context. Why did internees dress as Aboriginals, and what does this reflect about them and their circumstances? Is this a lark, an intentional demeaning of Aboriginal culture, or was it camp enforced? Where lies the agency? The Stories Were Not Told is replete with examples of photo artifacts in need of contextual anchoring. If this photo is an example of internee identification with another oppressed group this, for the purposes of history, should not remain unstated. These contextual and historical deficiencies hamstring the divining of historical significance.

A significant portion of Semchuk’s composition is intended as “memory work” aimed at communicating the temporal reality of human experiences while keeping in mind that subjective views of the past are, of necessity, flawed. It is not difficult to agree with protestations that what was done to internees was wrong, but the wrong did not occur in a vacuum. To see it thus renders the stresses incomplete and deprives the personal experience and collective cultural residue of some of its significance and also, I must add, deprives it of some of its power to evoke reconciliation and change.

There are a few minor technical irritants. The bibliography does not list archival sources, although the bulk of the photos are from Library and Archives Canada. Also, the District Ledger is a newspaper from Fernie, BC, not Lethbridge, Alberta (p. xliv). Michael Bahri’s arrest is given as 1920 when in-text references confirm that it was 1919 (p. 196). As well, the intention for the inclusion of this case of apparent wrongful conviction and execution could be much more pointed.

The bibliography is varied but closer research would have provided additional context on specific internee camps, such as the camp at Morrissey, BC, featured in Wayne Norton’s essay, “Refuge of a Scoundrel: Patriotism and William Bowser,” in The Ormsby Review no. 180 October 13, 2017. On the East Kootenay internments see also Wayne Norton, Fernie At War (Caitlin Books, 2017), reviewed by Keith Regular in The Ormsby Review no. 236, January 21, 2018. The anthology by Frances Swyripa and John Herd Thompson (editors), Loyalties in Conflict: Ukrainians in Canada During the Great War (1983), is a notable miss.

If the intent of The Stories Were Not Told is to place Canada’s past and current Canadians on trial, then its probative value is worthy of consideration. The photos have much to say, but Semchuk does not let or make them speak with evidentiary certainty. The stories come to us with the residue of ages, speaking through time but sometimes without context, apart from the certainty that internment camps with resident internees actually existed. Recall and memory are subjective, and as such make for uncertain evidence. Semchuk believes that the repression embodied in internment was motivated by Anglo feelings of superiority over others. Racist superiority was systemic to the time, but to ascribe it as the chief motivating force for internment requires confirmation, especially in the circumstance of total war with an infinite variety of national stresses and strains.

Semchuk’s stories and photos challenge these reluctant transgressors and their descendants to at least consider their truth and accept their rightful place in the collective memory. There is weight to her invocation of the use of “honest dialogue” to interpret the meaning in storied recall, while recognizing the natural tension between transgressor and victim because both believe themselves on the moral highroad. “Honest dialogue” can bring victim and transgressor to mutual understanding, with a recognition of the transgression as the basis for redress.

The Stories Were Not Told is an intriguing composition, stimulating thought and offering an artistic integrative approach to history and culture, and presenting evidence of historical multi-cultural intolerance while pressing an argument for multi-cultural accommodation. It encourages the reader to partake in the agony of upheaval and displacement and the personal and community uncertainties in uncertain times. It is a thoughtful, stimulating, and inventive approach to comprehending the past. This grounding of the human experience through a variety of approaches reveals more than history per se. It anchors us in the ordinariness of the life of the deprived and disappeared and allows the present generation to empathize with those past.

*

During World War I approximately 300,000 Chinese men were transported to the western front in France to serve the allied cause. Among them were 81,000, collectively known as the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC), recruited to provide manual labour for the British. The history of the CLC has escaped close scrutiny, and Dan Black’s foray into this subject, Harry Livingstone’s Forgotten Men: Canadians and the Chinese Labour Corps in the First World War, provides one of the few easily accessible and detailed sources. Black recounts the history of the CLC from recruitment through to the end of their engagement in 1920.

The book’s title suggests a narrow focus on Canada’s involvement with the CLC but Black, in an effort to make sense of a tale that spans continents and oceans, captures the national and international dimensions of CLC history. Black considers this an important segment of Canadian history waiting to be revealed, but what does he make of Canada’s part in this little-known history, and how does it fit with the theme of internment?

As early as 1915 China offered 300,000 military labourers and 100,000 fighting men to the allied cause, and yet despite the losses on the Western Front the offer was refused: a clear sign, perhaps, of western bias. International geopolitics were also at play and the decision not to accept Chinese military aid had to do with keeping Japan onside. Pressed by circumstances, however, the British began recruiting Chinese labour in 1916 with 3,000 men, followed by 4,000 per month starting in Jan. 1917. Britain decided not to work through a private contractor and instead recruitment was done through the British Emigration Bureau. Systemic racism aside, would the British and Canadian publics have given a positive reception to Chinese military aid with the knowledge that it might potentially spare the lives of some of “our boys”?

Fortunately, the West, and especially Canada, had an infrastructure in China that could be turned to recruitment. Canadian medical and Christian Missionaries, in particular, had successfully worked and proselytized in China for years, and by World War I were an influential presence. It was to Canadians, therefore, that the British turned to recruit their labour pool. Black attributes the social gospel mentality as the motivation for missionaries to engage as recruiters. The British government was only too glad to take advantage of missionaries’ familiarity with China, especially language fluency.

Regardless, recruitment was in all probability unlike anything the missionaries had experienced in preaching the gospel. It was aided and abetted by conditions in China that guaranteed no shortage of anxious and willing candidates. Although agreeing to immerse themselves in a twentieth century western military conflict, precisely what the Chinese understood about the dimensions of modern European warfare is anybody’s guess. The participants were not long in discovering that being indentured to Europeans proved little better than the poverty they had endured in China. How many thousands of the CLC had experienced military service in China, and whether or not this contributed to this European military venture, is unknown.

The CLC story is complicated, spanning as it does the breadth and depth of several cultures, the vastly altered settings and circumstances, and the lengthy and difficult travel by land and sea — while subjected to the foibles of unpredictable individuals and Canada’s national agenda. Needed by the British, but recruited by Canadians, these Chinese men were under contract to provide labour, not martial duty, and yet they were subject to British military law.

The holding camps, according to Harry Livingstone, the small-town Ontario doctor and on whose personal papers Black based much of his account, were essentially barbed wire mosquito- and bedbug-infested prisons complete with guards. Like prisoners, the Chinese were given numbered bracelets, were photographed and fingerprinted, and subjected to daily drill. The drill was surely questionable for men with practically no understanding of western military discipline. Inoculated against disease using a rudimentary health safety regimen often proved more deadly than the dreaded diseases. These were racially charged times and racial attitudes may have translated into sub-standard treatment, lack of concern or care, and acts of physical violence.

Although unfamiliar with western concepts of discipline, some members of the CLC would have understood the necessity for basic discipline and the consequence of non-compliance. Fierce caning or whipping in a manner as to induce personal shame, however, may have been beyond the comprehension of some victims and witnesses. A photo of such an event (p. 168) attests to the reality of the brutality.

There were challenges, both real and imagined, to delivering the CLC to the Western Front. Ships and trains were confined and restricted environments where individuals were challenged to deal with poor rations, boredom, sickness, freezing cold, and unfamiliar rules. The quarantine camp on Vancouver Island and the holding camp at Halifax presented challenges of crowding, fresh water, and health. Trains travelled across Canada under guard and with an intended secrecy that press reports indicate was largely a failure.

Canadian authorities endeavoured to keep CLC members from contact with local Chinese Canadians. This was thought necessary to prevent CLC attitudes towards service on the Western Front from being spoiled by perceived antagonistic attitudes towards the war among local Chinese. This aspect of Canadian war sentiment deserves interrogation on its own merits. Is it unwarranted, however, to translate this to a pro-German stance? Canadian authorities, no doubt, heaved a sigh of relief when the Chinese contingents were safely delivered at Halifax on outward-bound ships. It was at this point, for all intents and purposes, that the involvement of the Canadian state ended, although the personal involvement of individuals such as Livingstone continued.

For readers well versed in the atrocious conditions on the Western Front, the CLC’s experiences there can be both anticipated and imagined. Not unexpectedly, they continued to suffer the effects of systemic racism that included jokes, insults, and physical beatings, all compounded by language barriers. Bombing and shelling accounted for most CLC casualties. Accidents from the hard and dangerous physical labour killed and maimed scores more. Ten members of the CLC were executed by the British, all for murder against fellow CLC members or civilians. The part played by cultural isolation and mental trauma in this may never be known. Thousands who were victims of disease, misfortune, or casualties of war did not return home. There is little doubt that the CLC experienced the brutality of the Great War in all its fullness and fierceness.

The little-known history of Canada’s part in CLC recruitment to the western front makes for an intriguing story. Unfortunately, there are challenges to winnowing the story from the excess of detail and the sometimes oddly organized narrative that Black has delivered.

Both author and editor needed a firmer grip on an obviously large trove of material to form a directly delivered and less rambling story. Given the book’s subtitle, Canadians and the Chinese Labour Corps in the First World War, I expected more on the CLC experience on the Western Front. Although Black’s front-line discussion is instructive — discussion extends from pages 367-429, a rather small portion of the book’s 456 pages of narrative — it is disappointing in its brevity.

Some topics are diffused over several chapters and often contain insignificant details that distract the reader from the central narrative. Details of the train’s journeys across Canada and discussion of the William Head Quarantine Station near Victoria provide two such examples. It was sufficient for Black to point out that William Head accommodations were entirely inadequate for CLC numbers and a cause of concern for the well-being of those who were confined there. Built for at most 800 individuals, it hosted up to 4200 CLC and regular ships passengers. It was so overcrowded that some men had to be left to quarantine on the ship. Even when the camp was enlarged, it remained inadequate from a lack of fresh water. Predictably discomfort, despair, and death resulted.

Similarly, personal information in the manner of trivia on many of the main characters exceeds anything necessary and often has little to do with their official work with or their impact on the CLC. Harry Livingstone and Ernest J. Chambers, Canada’s chief press censor, are two such examples. Even minor characters get undue narrative space. Notable, for example, is Black’s account of the death of Canadian Private Frederick Maynard, accidentally killed by a stray bullet during an attempt to quell a revolt among some Chinese. Black devotes a paragraph of detail on Maynard denoting his birthplace, height, weight, his wife’s name, and the fact he was “missing the first finger and part of the second finger on his right hand.” As well, he supplied the gory details of his stomach wound, complete with protruding intestines and the time of day he died, (p. 417). While of a certain intrinsic interest, this is not germane to the history of the CLC.

Black appears especially distracted by inventories of personnel and offers them at will. He provides, for example, a list of twenty-two names, in both old and more recent spellings, and identification numbers (pp. 332-3), and another of deceased CLC labours consisting of fourteen individuals again listed by both names and number (p. 397). It is admirable that Black desires that these Chinese men be no longer nameless and faceless to history, but their inclusion in this way impedes his own narrative. Such lists would have been better in an appendix. Worse, the lists leave the impression that these men were more victims than participants.

Though Black presents a mountain of trivia, he makes little comment on previous Chinese experiences with Canada. Taking a one-dimensional view, he supposes the Chinese were, in the main uninterested in this country. The history of the Chinese in Canada and their work on railway construction, in logging and mining, and participation in service occupations suggests otherwise.

Of necessity, the CLC was transported across Canada by rail from Pacific to Atlantic en route to Europe. It was because of this brief Canadian sojourn that the topic loosely fits the internment theme. Hosted by Canadians on arrival at Victoria, these sons of China were isolated in guarded compounds until placed on guarded trains to be transported across Canadian territory — protected as much as possible from public gaze and knowledge — to be disembarked from Halifax while still under guard for the Western Front. For the duration of their contract, the members of the CLC led controlled and restricted lives whether in compounds, on ships, or on trains. Though engaged as free men, they were anything but once they came under the guardianship of their Canadian hosts and finally into the clutches of the British military.

It is this policy of guarded quarantine and restricted and guarded presence on Canadian soil that approximates Canada’s internee policy for “enemy aliens.” Paradoxically, the members of the CLC were anything but enemy aliens; in fact they were allies, if not in the military sense, then certainly in the reality of their contribution of physical labour in a war theatre on behalf of both Canada and Britain. Consequently, their treatment at Canada’s hands left much to be desired. Black has opened a window on a little-known aspect of Canadian history where much may yet be told.

Clearly, Canada’s internment policy during both world wars makes for dynamic and contested history, as these books show. As the past continues to be challenged by new findings and frameworks, the impact of interment history is qualitatively refined and its meaning and impact challenged. As illustrated by the works considered here, the dialectic gives no quarter to any imagined status quo. These three works illustrate the variety of approaches available to studying this particular aspect of Canada’s past and invite continued reflection while imagining a way forward.

*

Keith Regular is a retired high school teacher and principal who lives with his wife Anne in Cranbrook. He began teaching in Newfoundland before moving to Elkford Secondary School, in Elkford, B.C., in 1986, and retired from there in 2014. Keith holds a Ph.D. from Memorial University of Newfoundland and is a specialist in southern Alberta Native and newcomer economic interaction at the turn of the twentieth century. His book Neighbours and Networks: The Blood Tribe in the Southern Alberta Economy, 1884-1939, was published by the University of Calgary Press in 2009. Keith has completed a manuscript on the murder of Alberta Provincial Police constable Stephen Lawson in Coleman, Alberta, in 1922, and the subsequent hanging of his Italian immigrant killers after a trial that garnered national and international attention. He has a manuscript in progress on the famed train robbery at Sentinel, Alberta, and subsequent shootout and killing of two police officers, at the Bellevue Café, Bellevue, Alberta, in August 1920, and is in discussions with the Crowsnest Historical Society regarding potential publication. Keith enjoys researching Aboriginal history and the history of the Crowsnest Pass and Elk Valley.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] See D.J. Hall, From Treaties To Reserves: The Federal Government and Native Peoples in Territorial Alberta, 1870-1905, (University of Alberta Press, 2015), especially pp. 300-304.