#822 Home is where the memory is

ESSAY: There’s no place like home: our connection to meaningful places

by Joanne Crozier

*

We are pleased to present an essay by Joanne Crozier, There’s no place like home, as part of an ongoing collaboration between The Ormsby Review and Graduate Liberal Studies at Simon Fraser University, an interdisciplinary program that leads to the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies.

The Ormsby-GLS partnership will see the regular publication of essays, memoirs, book reviews, and indeed any kind of writing by students, past students, and faculty at GLS. Keep an eye on the Graduate Liberal Studies Journal on The Ormsby Review homepage.

Joanne Crozier’s memoir contains family and personal stories from Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and BC, which she connects to larger themes including origins, memory, displacement, migration, place, and home. She weaves stories of her adoptive family (the Croziers) with her birth family (the Laidlaws) as they immigrated from England and Scotland a century apart, and then branched out across Canada — Ed.

*

“I may not know who I am but I know where I am from,” wrote novelist Wallace Stegner in his 1955 memoir Wolf Willow, and these few words speak a universal truth.[1] While most of us spend our lives trying to make sense of our identities, we are all part of family trees with birth parents and a birthplace. But family trees extend beyond biological relationships; our bonds through adoption, marriage, or close friendship are considered part of our roots and so are the places where we grew up, and our experiences there.

This essay is an exploration of roots, attachment to home, and how displacement affects our emotional wellbeing. If families are like trees, then individuals are the seeds dispersed on the winds of opportunity — or oppression — to settle and sprout in new environs. Over the last two centuries, notes philosopher Charles Taylor, modern industrial societies have “involved mobility, at first of peasants off the land and to cities, and then across oceans and continents to new countries, and finally, today, from city to city following employment opportunities. Mobility is in a sense forced on us. Old ties are broken down.”[2]

Young adults in Western cultures were traditionally expected to leave “the nest” for work, marriage, or higher education, and to set up their own households. Today it’s just a matter of routine when we relocate to realize our personal desires, as Zygmunt Bauman asserts in Liquid Modernity, a book based on the increasingly fluid nature of late modern societies. Here, he references the contemporary demise of rootedness, and the “new fragility of human bonds. The brittleness and transience of bonds may be an unavoidable price for individuals’ right to pursue their individual goals.”[3]

Paradoxically, we break our bonds with home but we still want to feel connected to it.

*

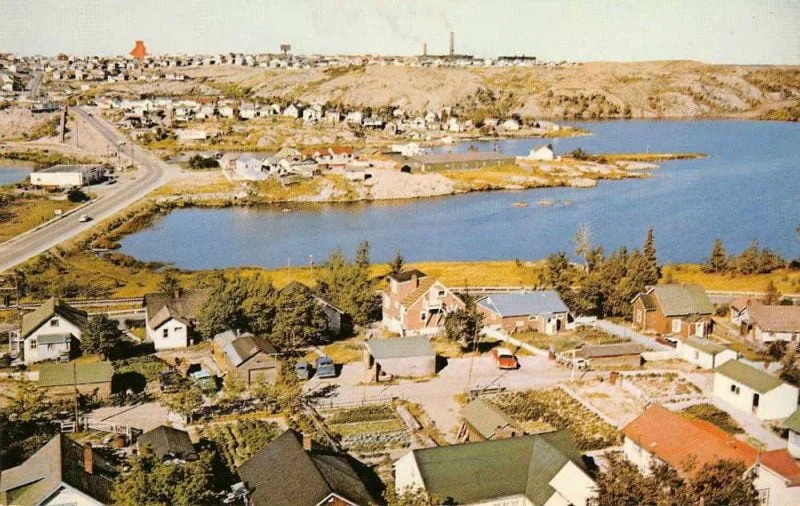

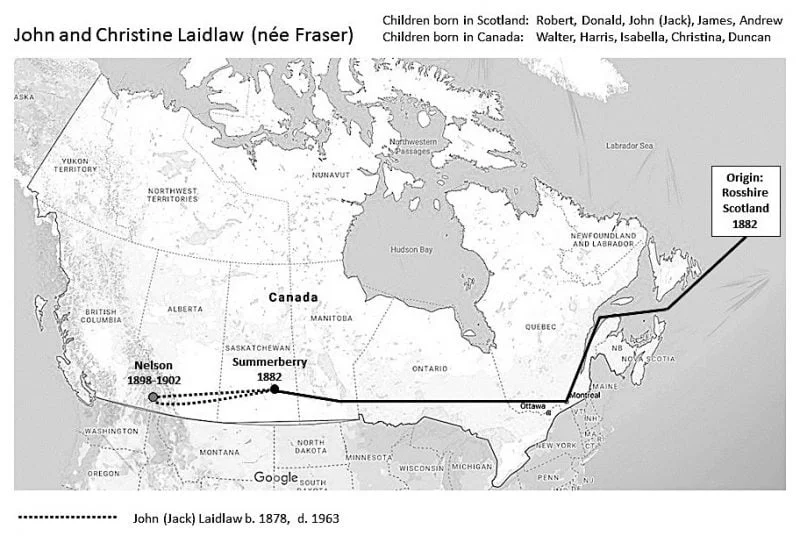

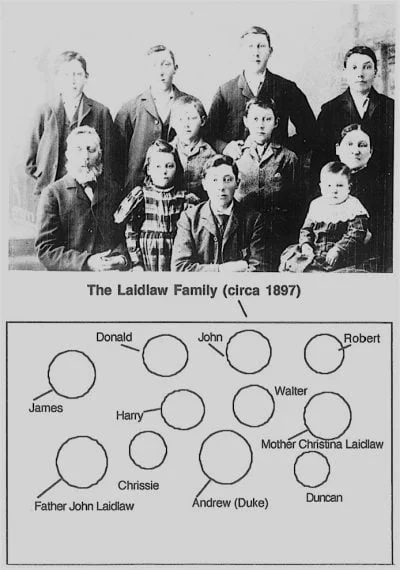

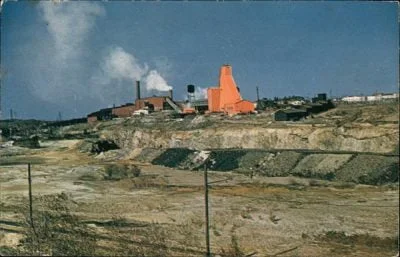

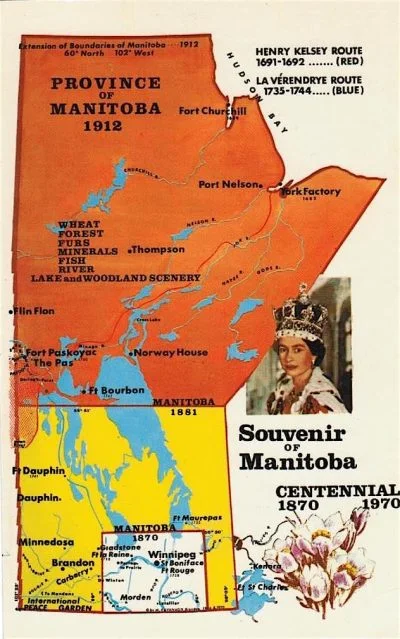

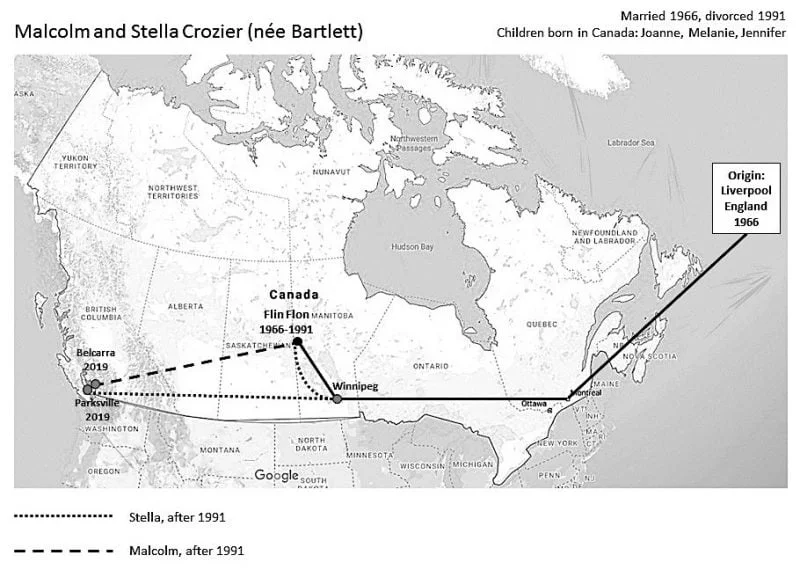

My family histories in Canada began when an emigrating couple left the Old Country to start a new life here. John (Jack) Laidlaw, my great great-grandfather on my biological mother’s side, emigrated from Scotland with his parents and siblings in 1882; their branch of the Laidlaw family tree took root in Saskatchewan, flourished there, and eventually spread across the country. Almost a century later, in 1966, my adoptive parents — Malcolm and Stella Crozier — moved from Liverpool, England to Flin Flon, Manitoba, a small mining town in the remote north, and adopted me as a baby; this is where I grew up. The Laidlaw and Crozier migrations, almost identical in distance and destination and undertaken in search of a better life, represent the stories of millions of immigrants who have settled, and will continue to settle, in Canada.

I’m proud of my Flin Flon heritage, but as an adopted child, I often wondered about the mysterious identities of my biological parents. An assignment to draw my family tree in Grade 4 crystallized the dilemma; my adoptive family’s roots were not my roots since we weren’t related by blood; did I rightfully belong on their family tree? And if not, then whose tree was I part of? Rubbing salt in the wound was the fact that I had two younger sisters who were not adopted; they “belonged.” An unflagging curiosity to know where I came from, and the strong desire to feel a sense of belonging, motivated me to start searching for my biological parents while I was in university.

At the time of my birth, adoptions in Manitoba were “closed,” or confidential, to protect the identity of the birth mother. When the provincial government finally opened the adoption records in 2015, I received my birth mother’s name, but it grieved me to learn that she had passed away 20 years earlier, just as I was starting my search. Fortunately, some of her family members kindly supplied me with information about my mother and other relations. This included a fascinating memoir by John (Jack) Laidlaw, written in 1954 to record the details of his family’s new beginning in 1882 as farmers near Summerberry, Saskatchewan, where my birth mother is buried.[4] At first I thought that visiting Summerberry would help me make sense of things, but I didn’t go; I felt no personal connection to the town, and since my mother had already passed away I couldn’t even share her memories of the place.

My lack of connection with Summerberry helps explain why my Flin Flon memories are so much stronger; Flin Flon is the site of the only childhood home that matters to me. Although I haven’t lived there for many years, I still feel an intense emotional connection, similar, I think, to Virginia Woolf when — she confided in her diary – she wondered why she felt “so incredibly and incurably romantic about Cornwall? One’s past, I suppose; I see children running in the garden … the sound of the sea at night … almost forty years of life, all built on that, permeated by that: how much so I could never explain.”[5]

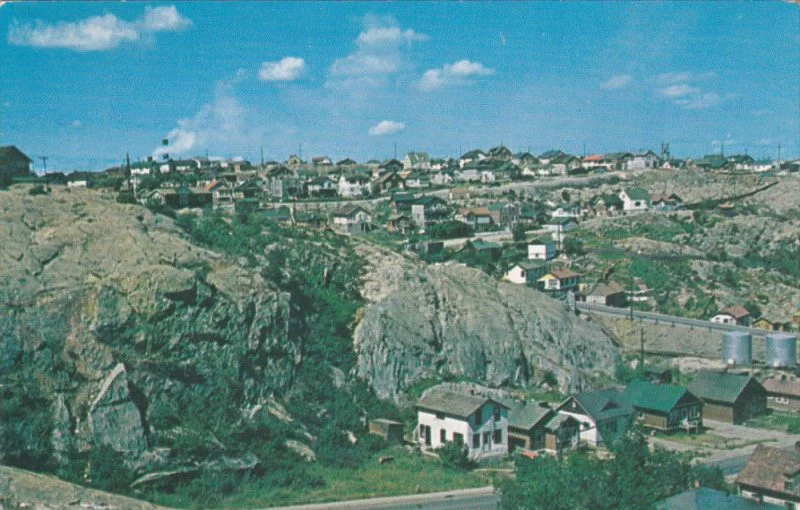

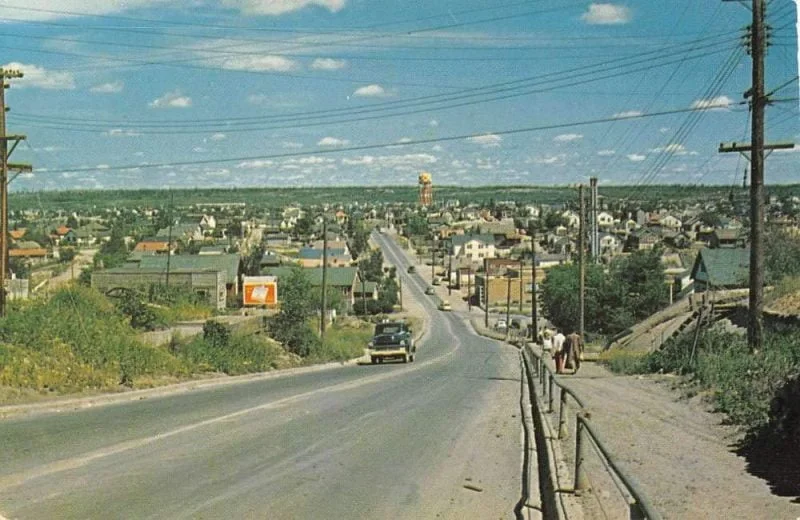

Childhood homes are special places that figure prominently in our memories and influence our adult identities, since, as urban geographer Clare Cooper Marcus explains, “for each of us, it was in the environments of childhood that the person we are today began to take shape.”[6] While my memories of home may not be wholly accurate, they are vividly detailed and triggered more easily with the passing of time, especially after I learned recently that Flin Flon’s copper and zinc mine may close, spelling the end for the town as we knew it.

Flin Flon, like every hometown, is fondly remembered by the generations that once lived there; their emotional, social, and cultural connections transform it from a generic space or environment to a meaningful place. Human experience creates places, and places are ascribed meaning by those who are attached to them. Homes, childhood environments, and sacred sites are places with significant meaning. So are neighbourhoods, cities, regions, and even small spaces like attics and cellars; a sense of place is not restricted by size.

Over the past 50 years, scholars have investigated our connections to place; sociologist E.V. Walter defined the phrase topistic reality as “the full range of meaning located as a place — sensory perceptions, moral judgments, passions, feelings, ideas and orientations.”[7] Homes in particular are affectively powerful places; only one hundred years ago it would have been common for a person to be born, live, and die in the same house or area, but this is rare today. According to human geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, “places are locations in which people have long memories, reaching back beyond the indelible impressions of their own individual childhoods to the common lores of bygone generations.”[8]

*

In this way, John and Christina Laidlaw settled and put down their roots in Summerberry, establishing it as the site of this Laidlaw family’s ancestral Canadian home. After John (Jack) Laidlaw’s brother was killed while logging in BC, his body was brought back and buried, as he recalled:

In the Summerberry Cemetery, just a few miles from my home. My Mother and Father also were buried there when they died. It was the custom in the old days when a person died, he or she was sent home to where the family had a plot in the cemetery…. That old custom is pretty well gone nowadays. Today I have two brothers buried in BC, [and] one buried in France across the ocean. So we are scattered.[9]

My birth mother, her mother, and her grandmother are also buried in the Summerberry Cemetery alongside their kin.

Clare Cooper Marcus emphasized the importance of place in our lives: “Since it is difficult for the mind to grasp a time period in abstract, we tend to connect with it through memories of the places we inhabited.”[10] I recall events from my past most easily when they are framed by the context of where my family or I were living at the time. Tweedsmuir, Queen Street, Wardlaw, South Drive, Falcon…these names bring to mind houses with yards in the suburbs, downtown heritage apartment blocks, condos towers, and a townhouse outside Vancouver. The shape of our physical dwellings has evolved considerably since prehistoric man found temporary shelter in trees and caves. When our nomadic ancestors settled, they built permanent residences ranging in diversity from African mud huts to Northwest Coast post and beam long houses.

Regardless of size and shape, a home’s primary purpose is to satisfy basic human requirements such as protection, warmth, and safety. However, dwellings also fulfill our higher level social and emotional needs such as bonding with family members, relaxing, and finding privacy for creative endeavours; as Virginia Woolf pointed out in A Room of One’s Own, “a lock on the door means the power to think for oneself.”[11] Further, according to Gaston Bachelard, our home is where “many of our memories are housed…. All our lives we come back to them in our daydreams.”[12]

The type of abode we choose expresses the values of both the individual and the community. A dwelling’s form and appearance were traditionally influenced by vernacular style, construction methods and materials, but the interior layout could be customized to suit specific functional and social needs. Modernity’s “unquenchable thirst for creative destruction…of ‘clearing the site’ in the name of a ‘new and improved’ design,”[13] writes Zygmunt Bauman, has stripped away vernacular architecture’s regional identity and interest, characteristics that are vital to imbuing a sense of place. As a result, homogenous and meaningless places are now a global phenomenon. However as humans, we both need and desire to assert our personal identities; our homes can be treated as an extension of our selves. We personalize our environments with decoration, landscaping and other alterations to create places that are as unique and individual as our fingerprints.

*

The Crozier family cabin on Lake Athapapuskow, about ten miles from Flin Flon, was just a three room shack without electricity or running water but my parents loved its rustic simplicity; as immigrants from post-war Britain, this remote cabin was where their Canadian dream of freedom and wilderness came true. They enjoyed the isolation as it was only accessible by boat and we had no neighbours. Cabin improvements kept my father busy: over the years he built a new boathouse, dock, deck and a three-room addition to the original cabin. Inside, the walls and gabled ceiling were panelled with wood, and large windows filled the rooms with natural light. My sisters and I carried in buckets of lake water and kindling for the old wood burning stove, which my mother somehow corralled into cooking our meals. At bedtime, we’d stumble along the dark path to the outhouse, and then lie snugly in bed reading comics by the amber light of a Depression era oil lamp. Once, I found an antique iron in the bush, which would have been heated on top of the range, and I wondered why anyone would need an iron in a place like our cabin! Living simply among these relics of the past, it was easy to imagine that we had been transported back in time to the previous century.

My memories of our cabin provide what Clare Cooper Marcus calls “a kind of psychic anchor, reminding us of where we came from, of what we once were.”[14] Thanks to my northern Manitoban upbringing surrounded by forests, lakes, and wildlife, today I am passionate about nature and the environment. As adults we are influenced by our childhood experiences, and these experiences are linked closely to the childhood environments from which the child “achieves a consciousness of roots, and the entire tree of his being takes comfort from it.”[15] My childhood recollections of our house in Flin Flon are not of rectilinear walls and ceilings but rather of sensations such as colour, sound, and texture. The houses on our street stood on a sloped rocky site, creating a green cascade of tiered backyards for play, or we could walk down the back lane to explore the scrubby ecosystem of Precambrian rock. We’d build forts in the bushes; I remember digging my hands under patches of verdant moss, pulling up slabs of the moist green velvet to carpet our hut’s rocky floor. Our neighbourhood was a natural playground such as those that, American environmentalist Paul Shepard wrote, he will “always remember with peculiar reverence, the…cherished trees or thickets, rock piles or dumps, basements and alleys.”[16]

Small rural towns are commonly portrayed by adults as conservative and cultural backwaters, but Flin Flon children could set out every day after school to explore the fringes, and beyond, of the wild landscape that surrounded us. We’d fall from trees or into creeks, and stoically ignore our bug bites, stings and other minor hurts. Participation in the fantastical schemes of our friends often ended in tears, but testing our limits was an important element of childhood and to paraphrase Nietzsche, if an injury didn’t kill us, it made us stronger.

When school ended in the summer, we’d move to our lakefront cabin, where I’d lie in bed in the morning listening to the sounds of birds and squirrels outside, or get up early and take the canoe out while the lake was calm, hugging the shore as I paddled from cove to reed-filled cove. Drifting silently in the shallows, I might cast a line, or just study the undulating weedy bottom in the shadow of the canoe. Occasionally the speckled lithe form of a northern pike would glide ominously past, a harbinger of doom for some unlucky fish or frog. Our summers at the cabin resembled Wallace Stegner’s in southwest Saskatchewan, which to him were “days of indolence and adventure where space was as flexible as the mind’s cunning and time did not exist.”[17]

My family lived in Flin Flon for many years but, as the old adage goes, change is the only constant in life. At the age of 13, I was sent to a private boarding school in Winnipeg. To move or to be displaced can be a difficult experience for a person of any age, regardless of the circumstances; in my situation, I was homesick and angry that my personal control had been taken away. Students at this British-style private school were strictly governed by rules and routines that included uniforms and curfews; I resented the loss of my previous independence. I rebelled constantly and came close in my first year to being expelled, but eventually I adapted to my new residence.

In the dormitory room I shared, each girl decorated her space with favourite photos of family and friends, and posters from home, creating personal and familiar environments that reminded us of the places we’d left. Homesickness can be a debilitating affective disorder with symptoms ranging from sadness to depression and apathy, but memories and reminders of home can sooth our raw emotions and help us adjust to a new reality. Nostalgia, from the Greek words nostos “homecoming” and algos “pain, grief, distress,” is the emotional by-product from the act of remembering. We enjoy feeling nostalgic but it is often tinged with melancholy for our youth, and a time that will never return. Similarly, English author Susanna Moodie emigrated to Canada with her family in 1832; their experiences are described in her memoir Roughing it in the Bush. She suffered acutely from homesickness, writing that “all my solitary hours were spent in tears… nightly I did return; my feet again trod the daisied meadows of England…I awoke to weep in earnest when I found it but a dream.”[18]

When my Laidlaw ancestors emigrated to Canada, they travelled west from Manitoba in a covered wagon to their new home in Saskatchewan. In John (Jack) Laidlaw’s memoir, he recollected that his “father and mother never said much about that trek across the prairie; it was too much of a heartache to talk about it. They must have been wonderful strong people to stand the hardships of that journey. Their minds must have turned to Scotland many times.”[19] Precisely why John and Christina Laidlaw emigrated is unknown to me. John worked as an estate agent and was probably not a landowner in Scotland; they already had five children, and so moving to Canada in hopes of financial gain would be my assumption. Waves of settlers left Scotland in conjunction with periods of severe economic depression, and the mid-1880s was one of these periods.

*

My mother struggled with depression and loneliness for a long time after leaving England and moving to Flin Flon. She didn’t enjoy small town life the way my father did, which is one reason they divorced after 25 years of marriage. Our family’s time in Flin Flon ended as we each moved away; my mother, sisters, and I landed all over the country, touching down temporarily in cities like Calgary, Toronto, Montreal, Halifax, and St. John’s. I completed my undergraduate degree at the University of Manitoba, and then moved west with many of my classmates, not to be with family but for the pragmatic reason that we could find work. In The Malaise of Modernity, Charles Taylor cites this type of migration as an example of instrumental reason when he described “all sorts of people who have designed their lives; where they are going to live, where they are going to move, what part of the world they are going to live in, in terms of getting the best job.”[20]

I now live in Vancouver, while my sisters are in Winnipeg and London, England; my mother settled in Parksville, on Vancouver Island, and when my father retired, he also moved to the West Coast. The scattering of my family members is typical in late modern societies, especially in Western countries that value individualism; today, Taylor points out, we “live in a world where people have a right to choose for themselves their own pattern of life…to determine the shape of their lives in a whole host of ways that their ancestors couldn’t control.”[21] Even my great great-grandfather John (Jack) Laidlaw left his parents’ Summerberry farm in 1898 to seek his fortune in BC, where he worked for four years in the logging industry. However, constant movement weakens our connections to home and contributes to a feeling of rootlessness, for “to always be on the move is, of course, to lose place, to be placeless,” as Tuan reminds us.[22] John (Jack) Laidlaw moved home again after four years on the west coast, but none of my immediate family ever returned to Flin Flon.

My sisters and I sometimes talk about visiting Flin Flon again to see our favourite places and share our memories. As restless teenagers we couldn’t wait to trade boring small town life for city living, but I have come to agree with Tuan that we can “be fully aware of our attachment to place only when we have left it and can see it as a whole from a distance.”[23] Revisiting a childhood home as an adult can prompt an emotional re-examination of our roots and identities, but what we find may be unexpected, or even disappointing.

One of my old Flin Flon friends recently visited Tweedsmuir Street where we both lived as children; her photos of our family homes made them look smaller and plainer than I remember. I fear going back and witnessing the inevitable deterioration of the places I loved; or worse, realizing that our small part in Flin Flon’s history has been forgotten, in a return to Stegner’s poignant lament of 1955: “I don’t want to find, as I know I will if I go down there, that we have vanished without trace like a boat sunk in mid-ocean … to find every trace of our passage wiped away.”[24] I’m certain that the Flin Flon of today won’t live up to my memories, as the protagonist in Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) discovered when he visited his old home and “experienced many unexpected emotions. Near the great elm tree, which is a quarter of a league from the village, I got out of the carriage…I stood there under that same elm which was formerly the term and object of my walks. How things have since changed!”[25]

Werther’s nostalgia, triggered by the great elm at Goethe’s fictional village of Wahlheim, illustrates how objects as well as places can remind us of happy memories. Clare Cooper Marcus noted that, as people age, they “value objects that evoke the past; that immigrants tend to value objects that remind them of home; and that women are more likely than men to value objects that symbolize social or emotional connections.”[26] I enjoy browsing in vintage collectible shops where I can explore “memory lane” in my imagination. Familiar items remind me of home, or inspire visual vignettes of my ancestors’ lives. I wander through displays of “working” antiques like kitchenware, crockery, and utensils that once belonged to a family of another generation. The history of Euro-Canadian culture can be mapped out by the relics found in second-hand stores, based on the progress of material technology: 19th century iron, wood, and earthenware, Bakelite and Depression glass of the 1930s, to the plastics and ceramics used in my childhood. In antique shops, flea markets and, as Stegner noted, in “the New World’s old places, not only books reinforce and illuminate a child’s perceptions. The past becomes a thing made palpable in monuments, buildings, historical sites, museums, attics, old trunks, relics of a hundred kinds.”[27] Mary Wollstonecraft described a similar sensation upon visiting the museum of Rosembourg in Copenhagen in 1795, where every object “carried me back to past times, and impressed the manners of the age forcibly on my mind…. It seemed a vast tomb full of the shadowy phantoms…. Could they be no more-to whom my imagination thus gave life?”[28]

When I lived in Winnipeg, I would drive out past the city limits to explore the abandoned farmhouses and barns dotting the flat landscape. I thought about the families who built their homes on the prairies like John and Christina Laidlaw did; how long did each family live there and why did they leave? I feel a melancholy similar to nostalgia when I see a once-beloved home falling apart, a feeling shared by E.V Walter as he watched bulldozers demolish a slum neighbourhood in Boston, and tried “to understand my own subjective response as I viewed the wrecking machines turning the place into a ruin….Could my feelings be dismissed as nostalgia even though I never lived in the West End? I wondered about the quality of life in that place, and what would happen to it now.”[29]

Even in the Lower Mainland where underused buildings are feverishly being demolished and then redeveloped, there are still empty residential areas of historic interest, like the Ioco Townsite in Port Moody. In this community built around 1920 for Imperial Oil workers, the now-vacant houses are slowly being reclaimed by the surrounding forest. The history that is lost when a community disappears is a disturbing thought, as John (Jack) Laidlaw recounted: “How long will the memory of these early pioneers remain after they are gone? To me it is a tragedy that men and women of such good, sound character, who left our country such a fine heritage, may one day be forgotten.”[30]

Compared to the great cities of the world, Vancouver is a relative newcomer and life here is defined by contrasts. There are the extremes of affluence and poverty; the integration of eastern and western cultures; those who support development versus the environment; the burgeoning population of new immigrants and the dwindling population of longtime residents. It is an unsettling place to live, since the attributes that make Vancouver so desirable (climate, culture, geography) also factor into the explosive growth and change that continue to transform the city. I moved to Vancouver 25 years ago and my new friends were all “ex-pats” too, coming from somewhere else; Bauman’s “family home” doesn’t seem to exist here: “not a found home or a made home, but a home into which one is born, so that one could not trace one’s origin, one’s ‘reason to exist’, in any other place.”[31] As a renter, I worried about rising rents or displacement through “renoviction,” but purchasing a home was beyond my means due to the high prices and competition for a limited housing supply. Many acquaintances eventually left Vancouver to return to their less expensive hometowns and other areas of Canada.

Today my husband and I live in a townhouse that we own outside of Vancouver. The complex was built about 35 years ago in the period leading up to Vancouver’s real estate boom, when individual units within multifamily developments were considerably larger than they are today. The buildings surround a grassy common, with mature trees, and in our back yard we created a small garden. The adjacent patio is my outdoor oasis; bounded by containers of sun-loving herbs, perennials, and fig trees, this is where I relax in warm weather listening to birdsong, the white noise of distant traffic, and the omnipresent sounds of construction. Robins nest in the shrubs or under our deck, woodpeckers rap on chimneys, geese fly overhead in V-shaped formations … suburban wildlife goes about its business as I sit quietly watching.

However, because we have the (mis)fortune of living near a new Skytrain rapid transit station, we may be forced to relocate if the majority of owners in the complex agree to sell our property for development as part of a strata “wind-up,” as it is known in BC. Regardless of the outcome, there will be a few more moves in our future. But I still dream about finding a place where I can put down roots and live in what Bauman described as that “kind of home, to be sure, which for most people these days is more a beautiful fairy-tale than a matter of personal experience.”[32]

I still don’t know who I am, but I know where I would like to be.

*

Joanne Crozier currently resides in Coquitlam. Born and bred in Manitoba, she joined the westward exodus to BC after graduating from the University of Manitoba in 1991 with a Bachelor of Interior Design. She is active in Vancouver’s design community, teaching design and colour theory at BCIT, working as a registered interior designer, and volunteering for the non-profit association Interior Designers Institute of BC. In 2018, Joanne joined SFU’s Graduate Liberal Studies program where her work has explored themes related to memory, material culture, and sense of place. She wrote this essay in 2019 for Stephen Duguid’s course, “Reason and Passion II.”

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] Wallace Stegner, Wolf Willow: A History, a Story, and a Memory of the Last Plains Frontier (New York: Viking Press, 1963[1955]), p. 23.

[2] Charles Taylor, The Ethics of Authenticity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003 [1991]), p. 59.

[3] Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Polity Press, 2000), p. 170.

[4] John (“Jack”) Laidlaw, “Reminiscences of John Laidlaw who came to Saskatchewan in 1882,” 1954. Memories recorded by Marion Eadie. Digital copy of original booklet.

[5] Virginia Woolf, edited by Anne Olivier Bell, The Diary of Virginia Woolf: 1920-1924 (Mariner Books, 1978), p. 103.

[6] Clare Cooper Marcus, House as a Mirror of Self (Conari Press, 1995), p. 20.

[7] E.V. Walter, Placeways: A Theory of the Human Environment (University of North Carolina Press, 1988), p. 21.

[8] Yi-Fu Tuan, “Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective,” Philosophy in Geography, Edited by Stephen Gale and Gunnar Olsson, D. Reidel Publishing Co., 1979, pp. 387-427; p. 421.

[9] Laidlaw, “Reminiscences.”

[10] Marcus, House as a Mirror of Self, p. 20.

[11] Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own. Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1929, p. 88. http://seas3.elte.hu/coursematerial/PikliNatalia/Virginia_Woolf_-_A_Room_of_Ones_Own.pdf

[12] Gaston Bachelard, Poetics of Space. 1958. Translated by Maria Jola. Penguin Books. 2014, p. 30.

[13] Bauman, Liquid Modernity, p. 28.

[14] Marcus, House as a Mirror of Self, p. 20.

[15] Gaston Bachelard, Poetics of Reverie: Childhood, Language and the Cosmos. 1960. Translated by Daniel Russell, Beacon Press, 1971, p. 20.

[16] Paul Shepard, Man in the Landscape. 2nd ed., Texas A&M University Press, 1991, p. 35.

[17] Stegner, Wolf Willow, p. 6.

[18] Susanna Moodie, Roughing It in the Bush. 1852. McClelland & Stewart, 1989, p. 89.

[19] Laidlaw, “Reminiscences.”

[20] Charles Taylor, “The Malaise of Modernity – Part 1”. The 1991 CBC Massey Lectures. CBC Radio. Posted Nov. 11, 1991.

[21] Taylor, The Ethics of Authenticity, p. 2.

[22] Tuan, “Space and Place,” p. 411.

[23] Tuan, “Space and Place,” p. 411.

[24] Stegner, Wolf Willow, p. 9.

[25] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther. 1774, p. 91. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

[26] Marcus, House as a Mirror of Self, p. 75.

[27] Stegner, Wolf Willow, p. 29.

[28] Mary Wollstonecraft, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. 1795, p. 167. Cassell and Company, 1889.

[29] Walter, Placeways, p. 6.

[30] Laidlaw, “Reminiscences.”

[31] Bauman, Liquid Modernity, p. 172.

[32] Bauman, Liquid Modernity, p. 172.

10 comments on “#822 Home is where the memory is”

Hi Joanne! I really enjoyed your essay! I found it while looking for family history information, and it sounds like you’ve got lots of it! I guess we are 3rd cousins, maybe 4th – my grandfather was Walter Laidlaw, John and Christina’s 7th child, who came out to B.C. about 1929ish. I’ve just co-written a book about my(our?) great-uncle Donald, who was a cowboy of some renown in B.C. from about 1915 until 1950. My dad, uncle, and a 2nd cousin (Duke) all worked for him when they were young men at the 105 Mile ranch. I’d be happy to send you a copy if you like. dan.laidlaw@gmail.com Again, great job on this essay. I’m going to share it with the family.

Thanks for sharing this, Joanne! It was a great read… I have so many great memories from all the time I spent with your family at both your home and cabin while growing up! I can relate, too, because I was also adopted and found my biological parents when I was 27. I moved away for school and then came back, and I have lived in Creighton for the past 28 years. Our door is always open if you ever make it back this way! Take care!

I enjoyed your reminiscing of your childhood in Flin Flon and Denare Beach. I grew up in FF and still have a rustic cabin on the Weir Road outside Denare, which we rarely get to now that we live in Thompson. Home is where the heart is. You can visit — but the changes jolt our memories.

I enjoyed reading this story, Joanne. I babysat you girls when I was a teenager and your dad was my dentist. I have 2 brothers still living in Flin Flon and love to return “home” at least once a year. There have been many changes since I left so I totally understand your fear of not recognizing places. I think it would be a fun trip for you and your sisters to take a stroll down memory lane! Best wishes on your journey.

Really enjoyed your reminiscing about your roots. Knew your Mom and Dad well and you and your siblings. My children Hillary and Jason were a part of the Flin Flon Aqua Jets. Your Mom coached along with Enid Hill if I remember correctly. You really should come back for a visit! I live on Lake Athapapuskow and have room for over night guests. Agnes Mills

Great read! Thx Joanne. Your aunt Linda was married to my brother Barton Longmore.

Hi Don, I’m going to see Linda in a couple of weeks, I will mention your comment! Joy’s cabin is another place where we spent a lot of time as kids; I have vivid memories of the cabin interior, swimming off the dock and all the stairs down to it. Take care, Joanne

HI! I Enjoyed reading your history of your thoughts and the places where you lived. I am In Flin Flon, born and raised. I knew your dad and he was my dentist! A lovely man. We also have a bit in common. Your Aunt Linda Longmore was married to my cousin Bart on my dad”s side. I keep in touch a little bit with Linda and AllisI I hope you don’t have to move to have to find where you belong once again. Wishing you all the Best going forward!

Hi Peggy, Thank you! When I see Linda and Rachel in a few weeks I will tell them about this connection. Don Longmore also commented on my essay; I was too young to remember the Longmore brothers in Flin Flon but I see their names on the FF Heritage Society facebook page fairly often. Take care, Joanne