#803 Species survival and adaptation

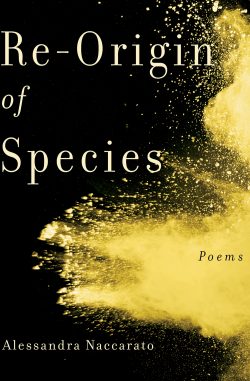

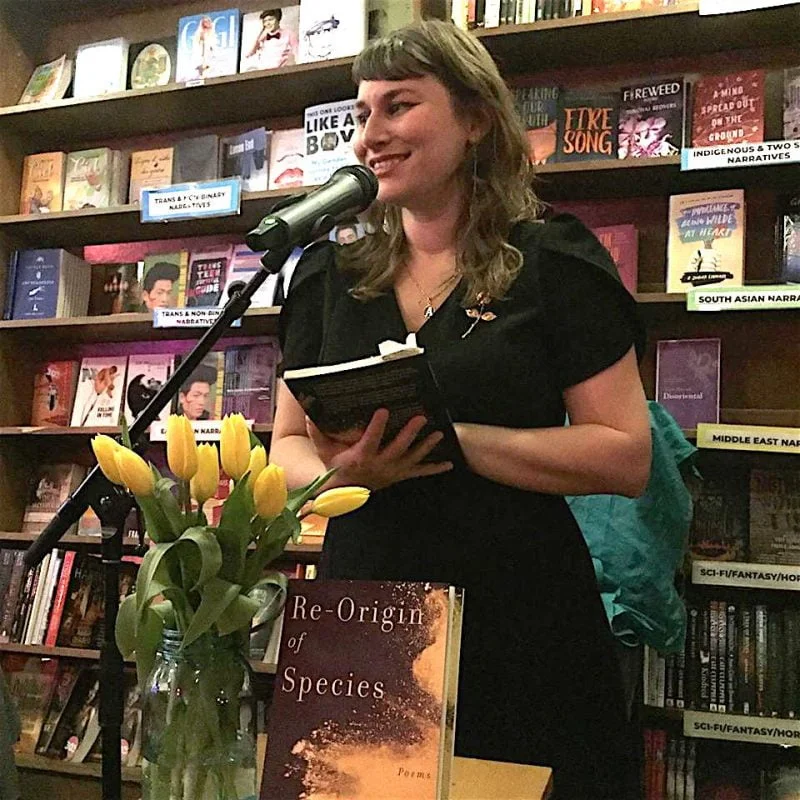

Re-Origin of Species

by Alessandra Naccarato

Toronto: Book*hug Press, 2019

$18.00 / 9781771665421

Reviewed by John Swanson

*

What does poetry do to work its magic? It relates knowledge of the world as we acquire it from science and by other means, with ancient knowing of a more mysterious kind: the forces at work in the “soul” (however you understand that term), the role of intuition in our lives, the non-rational that we need in order to understand fully who we are and what our place is in the world.

What does poetry do to work its magic? It relates knowledge of the world as we acquire it from science and by other means, with ancient knowing of a more mysterious kind: the forces at work in the “soul” (however you understand that term), the role of intuition in our lives, the non-rational that we need in order to understand fully who we are and what our place is in the world.

Sometimes when reading a book of poetry, we get a visceral excitement from the mystery of the language. The language in the poem, or the whole book, doesn’t always make logical sense but it creates a spell, an incantation, from the non-logical combination of words, ideas, sounds. And Alessandra Naccarato’s Re-Origin of Species is such a book – a fever dream of a book, a bath in the blood of creation. So many intersecting concerns – survival, adaptation, epigenetics, the patterns in nature, inter-species communication, virus, Lyme disease, warming of the planet, swarms, plagues, monocrop, suicide seeds, poisoning of the natural world and its denial in all its forms. The brief references in quotations, if you follow them, lead to an underworld of these informing concerns, like the miles of mycelium under the forest floor. You could think of these poems as the fruiting bodies of these many sources, among them the marvellous and passionate “The Life of Bees”, by Maurice Maeterlinck, and of course “On The Origin of Species” by Charles Darwin, but many others too, including the life events of the poet and her family and friends.

Naccarato is a devoted explorer of non-ordinary reality – intuition, inter-species communication, the ancient wisdom of witches and the goddess traditions, plagues and epidemics, the spirit of the hive; and she uses Fibonacci numbers that, among other things, define the pattern of the Golden Ratio in nature – the perfect and pleasing spirals in snail shells for example, and many features of the life cycle of the bees, a theme returned to in the book.

This is a woman-centred book. The women are big, grand, full of life force: “big-mouthed women, fat/ as trees, their ceilings hung with meat.” (from the first “Postcard”, p. 10) And they are connected to their ancestors – the mothers, grandmothers, great-grandmothers. Don’t enter here if you are afraid of the power of the feminine. But if you are not, you will find in Re-Origin of Species a feast from the natural world, eros, and mysterious combinations of language that you will not always understand but will create a world inside you by their effect. Sometimes the poet speaks like an Oracle, in riddles and half-sentences, naming the ineffable.

Instead of the more usual dedication to a person, Re-Origin of Species is dedicated “for survival”. As Darwin discovered, though he is often misquoted, a species’ survival depends on its adaptability and vigour, not only its strength.

And now to the book. I’ll talk about it in its five sections.

1. Postcards for My Sister

Postcards for My Sister consists of five poems that set the stage for Re-Origin of Species. The first and last poems bookend these scenes where “We have always taught each other/ how to give birth, and not”. The first begins: “Above the green village, a hill where no one lives/ our great-grandmother is buried there”, and the last begins: Above the green village, a hill where no one lives/ our grandmother is buried there”. The first describes the village before the earthquake, and in the last, the women still “spread their cards and drank”, but now, after the earthquake, “Big-mouthed women, stern/ as orchards, sending their daughters away”.

Each “postcard” is a picture of a place in the countryside, where grandmothers and great-grandmothers lie buried, where “big-mouthed women…/ made plans/ for daughters and weddings”, where a fawn lies, neck broken, on the beach, dies. Evasion, desertion – the unreliability of fathers. A life lived within the compass of women, and the earth.

2. Imminent Domains

Imminent – “likely to occur at any moment; impending.” The earth reclaiming itself from us. A haunting, created from a loss not well attended – result of our self-absorption. And climate change impressing itself on us by disease vectors created in part by us, by our failure to understand the sweeping forces we set in motion when we tamper with the natural world.

“This is How you Make a Haunting” (p. 17):

…

Hot oil in the pan. Fat mother

at the stove, battering (zucchini) flowers.

Seven years of black cloth, says

she’ll learn the language now.

Gives you his coat, the wool

inheritance. Here you are:

thin and shot full of poppies,

black-eyed eldest.

How you vomited beside the plot,

shook for days in your old room.

Mother skinning rabbits for soup,

brother holding a spoon of broth

to your small blue mouth.

A haunting, an imminent domain that will stay long after the event of her father’s death, which the narrator has arrived too late to be a part of.

“Imminent Domain — (Leilani Estates, Fissure 18)”:

…Peter

moved rocks to decorate

and deep in the night was shaken

by the old wives who guard

that place. We want to be forgiven,

by our mothers and the land: re-colonizer kids,

in our deep kisses and rum.

…The gash

in the earth laughs, the way planets laugh

at girls like me.

“In our Deep Kisses and Rum” — sex and getting wasted the preoccupations; but now beginning to see the great forces at work, as in 2018 when Kilauea volcano on the island of Hawaiʻi erupted in cracks and fissures close to homes. Imminent domain: likely to occur at any moment; impending.

And now an important theme in the book — infection, disease, wrestling with an epidemic – “It Could Be A Virus” (p. 27) and “Deforestation” (5 poems, pp. 28-32). In “It Could Be A Virus,” the angst of trying to name this illness:

It could be your mother. (inheritance) Could be the toilet seat

in fifth grade,

…

dental amalgams, or chemical injury.

It could be your personality. Your father’s silence,

…

Your malaria

treatment in a clinic with no running water, parasites,

…The tests came back fine

….

It could be the tick that bit you on the areola,

…

…It could be the wolves

they shot, the deer that overbred, until Lyme disease

went viral. It could be pollution, or loneliness.

Or maybe bacteria. It could all be your fault.

Lyme disease, a bacterial infection, has become an epidemic, and climate change is considered a cause of its spread, as well as being implicated in infestations of mites in beehives.

After so much denial by medical practitioners, we begin to blame ourselves for having Lyme. The poet catalogues the possible causes others have speculated, and the many doctors who speculate “depression” or difficult temperament as the “cause” (“It could all be your fault!”)

In “Deforestation — Gulf Islands, BC” (p. 28), “Deforestation — Lyme, Connecticut (p. 29), and “Deforestation — Long Point, Lake Erie” (p. 31), “blood is fine/ just thin.”

“Long Point, Lake Erie”:

Doctors say her blood is fine, just thin,

as she grows into an undiagnosed woman.

The re-abled know climate change is within us:

the zoonotic future, bacterial now.

(Zoonotic – disease transmitted from animals to humans.)

And as we are painfully aware in this era of coronaviruses, we are not in charge in the way we once thought. Our neglect of the environment may be a cause but we are inclined to blame the individual rather than our collective responsibility.

3. Creationisms (“from so simple a beginning, endless forms” — Darwin):

“Droughtland” (p. 34):

There’s a well under us, heaving itself dry. A death over us,

set in white sky. No witch begs for water. The witches piss

on ground so hot it hisses.

Such wonderful, evocative language – we are in it. You can hear the well pump heaving without producing water, like a dry vomit.

“Miscarriage” (p. 35):

Here is a complex poem, worth a comment on its structure. At the left margin, a sequence of stanzas following the progress of a hive, preparing to swarm, for the old queen to leave the hive and set up a new one, abandoning the old hive to a young queen. A scout dancing, signalling a new location in a universe of crop-dusted monoculture canola, a “droughtland” for the bees searching for a home.

The world is math disguised as colour

The poet invokes the Fibonacci number sequence, that describes the Golden Ratio, a pattern found in nature that is healthy, beautiful, including:

the reproductive pattern of honeybees:

the ratio of a healthy uterus

But then in the next stanza, she bemoans a world that is:

Monochromatic, pulped with dust

the hive can’t harvest… Infertility

a compass, white need turning

the queen from her land.

Indented and interspersed, a sequence of stanzas of the poet’s personal experience. Meeting the old fling in a

damp cafe…

the bee flies between us, barbs

into bone between my breasts

….

That old fling puts a hand to me

8 weeks later…

worried it was him.

So many wonderful touches of language here: for example, “he put his hand to me”, rather than “he put his hand on me”. Her choice of word here is both formal and intimate, in close, and holding her at a distance. The poet:

shudders; suddenly cramps. She

wakes in a puddle of honey, glistening

at the crotch. The stinger beside me

like a lost earring and everything so quiet.

A miscarriage – induced by the bee and its stinger? The trauma of the bees is visited on the poet; it becomes her pain and loss.

All is not right in the world.

In “Suicide Seeds” (p. 42):

…My friends’s uncle followed

his fields, to market, to coroner’s office.

Body already in repayment: skin blue

with crop dust, life remortgaged twice.

…More farmers take their lives than veterans

suicide rates are the highest of any occupation.

While Monsanto stands firmly by its commitment not to commercialize sterile seed.

“Generation Exodus” (p. 43) I will perform these signs among you — (Exodus 10)

I’m working in the bankrupt field

when I see them coming:

a thousand thousand mouths

in yellow heat, descending….

We’re returning to the land

we told the agent as we signed

the loan, subprime….

My wife by the shallow creek

each morning. She’s there

When the sky blackens. Runs

toward me, the field–under the swarm….

swarm over the land

devour everything growing

in the fields

…

Trillions rising

from the drought

…

How quickly a famine

is reborn.

The fields infertile, the plague of locusts, famine, terror, the loss of everything.

Signs, portents, like the 10 plagues visited on the Pharaoh during the exodus of the Jews from Egypt.

“Re-Origin of Species” (p. 47):

…

A headache like plates

shifting inside my skull.

That’s how it starts.

…

The CT

shows unorthodox, two skeletal

growths at forehead.

What use is a fell antler? No

longer reaching, god-struck.

They try to make me

comfortable. Drugged as the

first tip breaks skin, forehead

bloody in the morning

…

one law, multiply, vary, let

the strongest live

…

others will become rarer, extinct.

…

I antler, the way a cutting

grows new stem. Cover myself

and leave before they claim

what is left of my human.

The titular poem, imagining evolution from a human to a human with antlers, the antlers growing slowly, painfully, out of the narrator’s forehead. A new creature is born, in one lifetime. Here the poet turns a noun into a verb (“antler”), and an adjective into a noun (“my human”) – such a fine use of words that make the language her own, and she does this judiciously. And such evocative language, the antler fallen off – no longer reaching, no longer animated by the god.

4. Brood Awakening (“The cloud of cells, awakens, intensified, swarms” — from Robert Bly, News of the Universe)

“No Comment” (p. 54):

We’ve heard there’s a room where hooded women enter

to write dates on the walls with torn edges of fingers.

We’ve heard one can cypher these numbers to bodies,

to the graceless edges of some men’s beds.

And from “Northeast Blackout” (p. 57):

one D&C that summer, a circling of rapes,

boys who still showed up with 40’s and changed the music.

Another theme in the book: violence, abuse of power and rape.

“Letter to Self at 16” (p. 65):

We wear lipstick, a fake fur coat. Twelve in the woods

where is that back house

on chicken legs that wanders

dancing hut – (Baba) Yaga’s… Here is our rite of passage.

And:

Vasilisa faces an impossible task.

She has to carry fire back in a dead squirrel’s skull.

The second rule of girlhood is rapture.

In the fable, each of us survives.

Vasilisa is not a metaphor.

Vasilisa goes free.

Here is the possible antidote – the heroine’s journey. Baba Yaga is “a many-faceted figure: Snake, Bird, Earth Goddess, totemic matriarchal ancestress, female initiator” (Andreas Johns). Here is the mystery of the impossible task assigned, and the young woman learning by her intuition to enlist the powerful female initiator to her cause.

And continuing with the poem:

Those before did not have jobs,

they had initiations

& still do.

Us, we were how they read the future a cloak of bees

no singularity –

…

the Greeks

called us Graces.

Wax: light hardened, light made soft again.

Ancient geometry: the hexagon opens, epigenetically.

“There is one masterpiece, the hexagonal cell” (Maurice Maeterlinck, The Life of the Bee). Honey and sweetness in the hive in a tightly packed form (the hexagon). But what does the poet mean when she says: “the hexagon opens, epigenetically”? This suggests that some process may be happening that will increase the evolvability of a species. “An epigenetically inherited element can act as a “stop-gap”, good enough for short-term adaptation that allows the lineage to survive for long enough for mutation and/or recombination to genetically assimilate the adaptive phenotypic change” (Wikipedia).

For us humans, does the trauma of the Holocaust, for example, get passed on in some way from its survivors to their descendants – as a way of coping with trauma, or does the trauma embed in descendants of the traumatized, as a predisposition to depression? And what of our unavoidable adaptation to the many versions of coronavirus that we will have to live with? And the inevitable warming of our planet? Perhaps we will be entering a storm of epigenetic adaptations to environmental changes – Re-Origin through epigenetics.

5. Autogenesis

This section, the coda of the book, consists of 22 poems without titles. The poems begin with:

The bathtub in the garden is filled with bees

…I call them here

as instrument

and lay the man

into the barbed ceramic tub

humming

I am trying to forgive you

I shout though the drones lick his ears

and when he rises

blessed by ten thousand stings

I offer barrels of water…

wash yourself

I order

though he does not know I am here

…it helps

to study pain inside the other…

And continues with:

In the garden, a queen breaks hexagon to flower, to find the mites

abound. The singular

erases itself, not into marriage

but the natural law of slut: contagion,

creation.

(“the natural law of slut” — catching disease, getting pregnant, this is how we have used the word so carelessly in our time. But such a resonant phrase, and as we reclaim the word, the deeper meaning hints at the polymorphous fertility of the Beltane feast.)

In the garden, a maiden queen arises to find her drones

abound. After the death

of monocrop in the valley; no more sweet glyphosate breeze,

her sex begets an ecosystem. Contagion,

creation, trophic cascade.

(“trophic cascade” — where the organism fits in the food web)

O see thy colonies lifting, queen.

O find thy way back home.

…

Up on the hill, mist. Two vultures circle,

looking for snakes in damp grass.

A girl in red contemplates the snakes.

…

In her red dress, that girl is humming.

The way stories end, on a hilltop, slowly.

Black snake in the mouth of the celebrant bird.

It’s hard to pin down the meaning of this image but it reminds us of Baba Yaga as Snake, Bird and female initiator; and it resonates with the natural state of the world in which there is a certain kind of order that we are part of but do not control.

*

Re-Origin of Species is a riveting, ambitious book that delivers on its ambition. A litany of sorrows for the world as it is, and a prayer for the future. I followed many of the quotes in the book and found them passionate and enriching. Especially inspiring was The Life of Bees, by Maurice Maeterlinck.

As in Wiccan practice, “what is re-membered lives”.

*

John Swanson’s book of poems and street photographs, an almost hand, beckoning, was published by Blurb Books, San Francisco, in 2019. It was reviewed by P.W. Bridgman in The Ormsby Review (no. 586, July 30, 2019). John Swanson lives in East Vancouver.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster