#799 Murder at the Sumas settlement

The Trials of Albert Stroebel: Love, Murder and Justice at the End of the Frontier

by Chad Reimer

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2020

$24.95 / 9781773860206

Reviewed by Kathryn Neilson

*

The Trials of Albert Stroebel chronicles the 1893 murder of John Marshall, a farmer on the Sumas prairie, and its consequences for his one-time friend, Albert Stroebel, who was convicted and executed for the crime. There were no witnesses to Marshall’s murder and so the case against Stroebel was entirely circumstantial. Chad Reimer’s meticulous research provides a detailed and entertaining account of the murder investigation and the frontier proceedings that led to Stroebel’s execution, and ultimately asks whether justice was done.

The Trials of Albert Stroebel chronicles the 1893 murder of John Marshall, a farmer on the Sumas prairie, and its consequences for his one-time friend, Albert Stroebel, who was convicted and executed for the crime. There were no witnesses to Marshall’s murder and so the case against Stroebel was entirely circumstantial. Chad Reimer’s meticulous research provides a detailed and entertaining account of the murder investigation and the frontier proceedings that led to Stroebel’s execution, and ultimately asks whether justice was done.

Reimer’s vivid portrayal of the Sumas prairie and its late-19th century denizens will be of interest to anyone familiar with this region. Forty miles east of Vancouver, the prairie straddles the border and was sparsely settled by white immigrants who stayed to farm following the Fraser gold rush. Connecting rail lines built between Mission and Bellingham in 1891 produced a brief population and economic boom. By 1893, however, the area faced a global depression and the rail lines had become a path for destitute transients.

Marshall and Stroebel were “two men liv[ing] ordinary lives on the edge of a closing frontier” who would have escaped notice but for the murder (p. 7). Marshall, a Portuguese immigrant, had established a productive farm on the prairie and had recently spoken of taking a wife. Stroebel, a 20-year-old American, came to the area seeking work as a handyman to support his younger siblings. Small in stature and crippled in his right leg, he was nevertheless viewed as a hard worker and a “good boy.” He sometimes worked for Marshall and the two developed an “unlikely friendship” (pp. 11-12). Stroebel had recently fallen in love with Elizabeth Bartlett, the 12-year-old daughter of the owners of the local hotel, and they hoped to marry once he made a sufficient living to support her.

On the morning of April 20, 1893, a neighbour discovered Marshall’s body on his front porch with two bullet holes in his head. Authorities were alerted and general turmoil developed at the crime scene as the community gathered to speculate on the identity of the killer and await the arrival of the nearest police and coroner from New Westminster, a three-hour train ride away.

Reimer’s archival research, particularly his use of comprehensive records of Stroebel’s trials, provides an engaging and realistic account of the ensuing investigation and legal proceedings. As well, Marshall’s murder attracted significant interest among reporters on both sides of the border who broadcast the events widely, luridly and not always accurately. Reimer adeptly employs these news reports and, where necessary, provides credible surmise to close gaps in the tale.

The murder investigation was rapid and, at times, of questionable legality. Marshall had last been seen alive on the afternoon of April 19, 1893. It was apparent that two people had dined at his table that evening and there was no sign of a struggle in his home. Marshall was known to be a man of some wealth and to have perhaps considered marrying Elizabeth Bartlett. A pathologist recovered the two bullets, which had been shot from a 38-calibre pistol. Stroebel owned such a pistol, and a sometimes-marshal of Sumas tricked him into relinquishing the gun, then planted two empty cartridges where they gave rise to suspicion. When questioned, Stroebel maintained he had not been near Marshall’s home that evening, but had to change his story when neighbours reported otherwise.

There was, however, no evidence of robbery. Thirty-eight-calibre pistols were not uncommon and attempts to link the retrieved bullets to Stroebel’s gun were rudimentary at best. “Tramps” were regularly seen in the vicinity of the farm, and one had recently worked for Marshall. Community opinion was divided but many saw Stroebel as an unlikely murderer by nature and by reputation.

On April 23, 1893, the authorities decided there was sufficient evidence to arrest Stroebel, and he was taken to the New Westminster Gaol to await trial. Reimer observes he faced this prospect at a significant disadvantage:

The first two decades of Stroebel’s life contained more than its fair share of trials and tribulations. A broken family, lack of material resources and a meagre education left him ill-equipped to navigate these trials. His biggest asset was an offbeat optimism: again and again he tried to escape the life he seemed destined to live, but too often his actions and decisions would only make matters worse (p. 13).

Reimer provides a sterling portrayal of the late-Victorian prisons and courtrooms of New Westminster, their inhabitants and, at times, even the prevailing weather. His descriptions are enhanced by biographies and archival photographs of Stroebel and of the judges and lawyers who took part in the proceedings, several of whom had held high positions in the provincial government.

Complications arose when, prior to the trial, David Eyerly, a Sumas bully and rogue, unexpectedly confessed that Stroebel had invited him to help rob Marshall and that Stroebel had shot the farmer while Eyerly stood lookout. Eyerly was accordingly charged, imprisoned, and set to stand trial with Stroebel. He then recanted his confession. Both men nevertheless proceeded to trial on November 13, 1893 before a judge and jury.

Complications arose when, prior to the trial, David Eyerly, a Sumas bully and rogue, unexpectedly confessed that Stroebel had invited him to help rob Marshall and that Stroebel had shot the farmer while Eyerly stood lookout. Eyerly was accordingly charged, imprisoned, and set to stand trial with Stroebel. He then recanted his confession. Both men nevertheless proceeded to trial on November 13, 1893 before a judge and jury.

The Crown maintained that Stroebel’s friendship with Marshall gave him the opportunity to commit the crime, and he murdered the farmer “for money and love:” he was too poor to marry Elizabeth and jealous of Marshall’s interest in her. Questionable “expert” evidence linked the two bullets to Stroebel’s pistol. The defence argued that a transient tramp had killed Marshall, and Stroebel testified he had not been near Marshall’s farm on the evening of the murder. It will be of interest to some readers that the trial took place shortly after changes to the Criminal Code that, for the first time, allowed an accused to testify on his own behalf. Stroebel was thus one of the first offenders to take the stand to defend himself. The confession and recantation by the mercurial and malicious Eyerly created complexities for both parties. At the end of the seven-day trial the jury was “hung,” unable to reach a unanimous verdict.

The Crown dropped charges against Eyerly and set a second jury trial against Stroebel in Victoria to avoid delay. While many of the same witnesses testified, the Crown had used the first trial to its advantage in strengthening its case. Better firearms experts were found, and the difficulties presented by Eyerly’s contradictory statements were gone. Most significantly, the trial judge demonstrably and repeatedly favoured the Crown’s case, permitting the Crown to rely on Stroebel’s evidence from the first trial, and intervening rudely and inappropriately during the defence case. His charge to the jury departed from permissible legal instructions to the point that he “persistently and forcefully tilted the court against the defence” (p. 187). At the end of the 12-day trial Stroebel was convicted of murder, sentenced to be hanged, and remanded to death row.

The Crown dropped charges against Eyerly and set a second jury trial against Stroebel in Victoria to avoid delay. While many of the same witnesses testified, the Crown had used the first trial to its advantage in strengthening its case. Better firearms experts were found, and the difficulties presented by Eyerly’s contradictory statements were gone. Most significantly, the trial judge demonstrably and repeatedly favoured the Crown’s case, permitting the Crown to rely on Stroebel’s evidence from the first trial, and intervening rudely and inappropriately during the defence case. His charge to the jury departed from permissible legal instructions to the point that he “persistently and forcefully tilted the court against the defence” (p. 187). At the end of the 12-day trial Stroebel was convicted of murder, sentenced to be hanged, and remanded to death row.

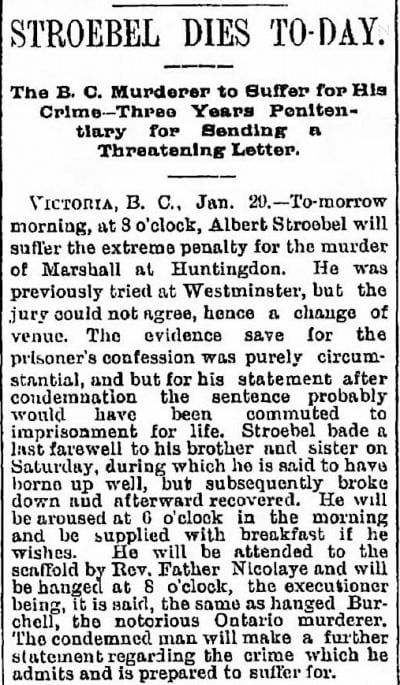

Stroebel’s conviction was not, however, the final chapter in his story. While he awaited word on whether review of his death sentence by cabinet and the Governor-General would lead to clemency, new information came to light that, if available earlier, might have led to a different verdict. The nature of this is best left for the reader’s discovery and consideration. It emerged too late to have any impact, however, and on January 24, 1894 Stroebel received word that his sentence would not be commuted. On January 30, 1894, he was hanged.

Stroebel’s conviction was not, however, the final chapter in his story. While he awaited word on whether review of his death sentence by cabinet and the Governor-General would lead to clemency, new information came to light that, if available earlier, might have led to a different verdict. The nature of this is best left for the reader’s discovery and consideration. It emerged too late to have any impact, however, and on January 24, 1894 Stroebel received word that his sentence would not be commuted. On January 30, 1894, he was hanged.

Reimer’s last chapter, “Endings,” provides a denouement. After describing the aftermath for key witnesses, he embarks on a retrospective analysis of the case against Stroebel — the “what-ifs” and “unanswered key questions.” These develop into his own speculations of what happened and conclude with this fitting epitaph to the book:

These what-ifs and speculations have taken us some distance away from what we know of Albert Stroebel’s life and death, and what we know is enough to tell a good story: at times hopeful, at times pathetic, mundane in most parts, exceptional in others (p. 229).

The Trials of Albert Stroebel will be of interest to participants in the criminal justice system and to legal historians. Reimer recounts the widely-held belief in the early years of the province that its justice system “represented the very best in British law and order” (p. 147), evidenced in news reports that Stroebel’s conviction “demonstrated ‘the fairness, thoroughness, and promptness of British justice” (p. 193). Yet the frontier justice Stroebel received was in fact rough, ready, and of questionable fairness. Inexpert expert testimony, slack regard for evidentiary rules, and the arrogant conduct of the presiding judge justifiably lead to questions of whether justice was indeed done on that day in Victoria in late January, 1894.

*

Kathryn Neilson is a retired lawyer and judge. Her legal career in Vancouver included government service as Crown Counsel, as well as private practice in civil litigation and administrative law. She was a part-time adjudicator for the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal, and also worked in the field of international human rights in South Africa and in Cambodia, where she spent a year with the United Nations as a human rights officer. She was appointed to the Supreme Court of British Columbia in 1999, and to the B.C. Court of Appeal in 2008, retiring in 2016. Ms. Neilson has served on a number of professional and community boards and committees. During her career she periodically taught part-time at the law schools of U.B.C. and the University of Victoria, and in the Department of Criminology at Simon Fraser University. She was also engaged in continuing legal education courses for lawyers and judges. She has published papers on diverse legal topics and on her experiences in Cambodia.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster