#793 Sons, fathers, and fatherhood

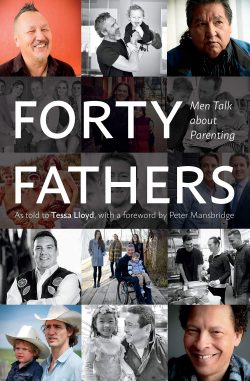

Forty Fathers: Men Talk About Parenting

by Tessa Lloyd, with a foreword by Peter Mansbridge

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2019

$34.95 / 9781771622431

Reviewed by Trevor Marc Hughes

*

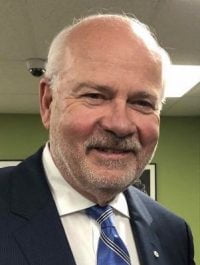

From Peter Mansbridge’s foreword to Tessa Lloyd’s Forty Fathers: Men Talk About Parenting, it’s clear that this iconic CBC figure regretted not having spent more time at home with his children, “doing the things fathers are supposed to do.” Mansbridge provides a good segue to the themes of Forty Fathers, including regret, grasped or failed good intentions, and the importance of connection — or the lack of it.

From Peter Mansbridge’s foreword to Tessa Lloyd’s Forty Fathers: Men Talk About Parenting, it’s clear that this iconic CBC figure regretted not having spent more time at home with his children, “doing the things fathers are supposed to do.” Mansbridge provides a good segue to the themes of Forty Fathers, including regret, grasped or failed good intentions, and the importance of connection — or the lack of it.

I’ve been fortunate. As a stay-at-home dad for both of my sons, I loved the chance to build a strong bond with them. On occasion, when possible with my wife and my boys, I have travelled around British Columbia by motorcycle to gather material for my own stories; but increasingly I feel a wish, even though I’m not gone for long, to leave my motorcycle in the driveway and make the most of my limited time as a dad while I have my sons at home.

Tessa Lloyd states early on in Forty Fathers that men fulfilling their potential as dads can make for possibly the most valuable experience they’ll ever have. A Victoria counsellor who has worked extensively with fathers, Lloyd has found in her travels that dads often have nowhere to express themselves about dadhood.

So in interviews with many prominent Canadian men, Lloyd sought to learn their thoughts about their own fathers and their experiences once they became parents themselves. Several times the reader hears that there is no such thing as being ready, and that dads bring their existing “beliefs, values, attitudes and patterns of behaviour” to the table. Early in Forty Fathers Lloyd notes that “it’s a confusing time to be male” where mainstream media plies us with male stereotypes endorsing dominance, power, and hyper-masculinity in which the role of nurturer doesn’t really figure. These conventional messages can limit male potential, especially when it comes to experiencing a fulfilling fatherhood.

Musician Alan Doyle starts things off with generational differences, such as how parents letting kids out of their sight is considered irresponsible nowadays. As a dad, he feels he must occupy his son with activities, rather than letting him play outside unsupervised like he did when growing up in Petty Harbour, Newfoundland. Both his parents practised “benign neglect,” he says. About his own fatherhood, Doyle tells it like it is, stating that he’s missed out as a dad while committing to his professional responsibilities, such as a tour with Sting. If you’re not careful, he tells us, you’ll miss out on something far more precious.

Several contributors to Forty Fathers reveal that a father figure can be assembled from different members of the community. Art Napoleon, cultural educator and former chief of the Saulteau First Nation at Moberly Lake in northeastern BC, remembers his dad as “casting a long shadow” and soon leaving him to be raised by his grandparents. Although his grandfather had a great deal of traditional knowledge, he battled alcoholism and his grandmother was the one providing a solid parental figure. His uncles influenced him, as they had a strong work ethic and were “hunters, trappers, hard workers.” Eventually, on moving to Victoria, he found a “spiritual and philosophical mentor.” As a father, he’s found himself battling drinking and struggling in bumpy relationships, but he holds tight to the beliefs that a dad is “someone who teaches and protects,” who is available and who pays attention.

It’s the being there and not being there, the emotional absence and the habitual stoicism, that crops up several times in Forty Fathers. UBC Anthropologist Wade Davis recalls that his father was an approachable, decent, and ethical man, but “he was part of a generation unprepared to speak about their emotions.” He found, over time, that a chasm had opened as their lives diverged, and there had been little reconciliation by the time of his father’s death. In experiencing fatherhood himself, Davis discovered that he had “never before experienced true selfless love.” He certainly has travelled in his career, in contrast to his father’s lack of travels, but when he came home he tried to be very present for his daughters when they were growing up. “When I was home I was really there.”

At first glance, Forty Fathers seems like the ideal look at fatherhood in the Instagram age, with photographs of Lloyd’s chosen personalities showing happy and smiling fathers, children, and grandchildren, but these images sometimes contradict the challenging times faced by the dads in the stories they relate here. This, however, does not take anything away from those stories, as often the contributors courageously and candidly tell of their moments of fatherly failure. As a result, Lloyd adds complexity to figures who we may hold in high esteem and regard as indefatigable, and who we might have assumed were incapable of parental shortcomings.

For example, in describing his own father, Justin Trudeau makes it clear that Pierre Trudeau was a man of his generation doing his best in a challenging leadership role. “He was an extremely sensitive, emotional man, but he was trying to be so together and so reasonable. He kept it all inside.” In experiencing a divorce, Justin Trudeau found a father figure in his stepdad, and eventually found his place as a teacher on his own terms. But in choosing public service as a second career, Trudeau now struggles with the very balance that his dad had to contend with. As a father now himself, he says he’s “shaping the world around my kids in whatever way I can,” and he now looks back on his father’s precedent “as an example of how to find balance and remain an effective leader.”

There is much wisdom to be found in the pages of Forty Fathers, almost exhaustingly so. It’s the kind of book where readers can read one or two instalments, then put the book down to think about the life lessons within. Many of the stories will have readers seeing prominent Canadian figures in a whole new light, one in which no matter how impenetrable their outward personas might seem, as fathers they were as vulnerable to failure and in need of assistance from time to time as the rest of us. It’s a kind of social leveller, fatherhood. No matter how prolific a career these men have had, none were handed an instruction manual when their children were born. They fell back on what they knew. They were influenced by their own fathers, whether they actively took on their traits or not.

It’s also clear that, in the twenty-first century, men are still struggling to be taken seriously as primary caregivers. Actor Paul Sun-Hyung Lee was a stay-at-home dad for his boys for a time early on in their lives. He decided to break with tradition and be the primary caregiver while his wife was the breadwinner. In the end it became an opportunity to build a relationship with his sons. “I wouldn’t trade those years with my boys for anything,” he states. But he still thinks primary caregiver dads “need to be given more of a break,” and that society needs to reconsider its “built-in bias” and accept them as nurturers by choice.

Forty Fathers also laments a tendency in the media to present fathers as detached, bungling, foolish figures, a portrayal that doesn’t help them shake stereotypes of emotional inaccessibility and stoicism that might have been present in their own fathers. Instead, in this book we see examples of dads embracing fatherhood and all its joys, and discovering parenting as a place of strength and success in its own right. Making fatherhood a priority is a great leap, and Forty Fathers teaches by example in many chapters where contributors reveal that they learned great things from their own fathers to the lasting benefit of successful careers and relationships.

One of these examples is Rick Hansen, whose own father suffered a workplace accident when a telephone pole landed on him, trapping him and breaking his hip. Seeing his father “stay active and move on with his life after the accident had a very positive influence on me,” Hansen writes. He also diverged from his father’s parental style when he and his wife Amanda shared in raising their daughters. He admits that his dad was “protector, provider … he was CEO of the home,” a fathering style that didn’t mesh with his son’s values. Hansen chose his own path, having “evolved significantly from where my dad’s was.”

Tessa Lloyd, in seeking “a departure from any prescriptive how-to manual,” has succeeded in Forty Fathers not only in pointing out the universality of the joys, lessons, and difficulties of fatherhood, regardless of a man’s profession or place in society, but also in giving fathers a practical anthology of stories to learn and seek guidance from.

*

Trevor Marc Hughes lives in Vancouver with his wife, Laura, and his sons Michael and Marc. He has travelled across the province by motorcycle and written two books on the subject of his journeys: Nearly 40 on the 37: Triumph and Trepidation on the Stewart-Cassiar Highway, and Zero Avenue to Peace Park: Confidence and Collapse on the 49th parallel. More recently, he edited Riding the Continent, a memoir by B.C. writer and naturalist Hamilton Mack Laing of his dogged motorcycle journey across the United States in 1915 (Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2019).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster