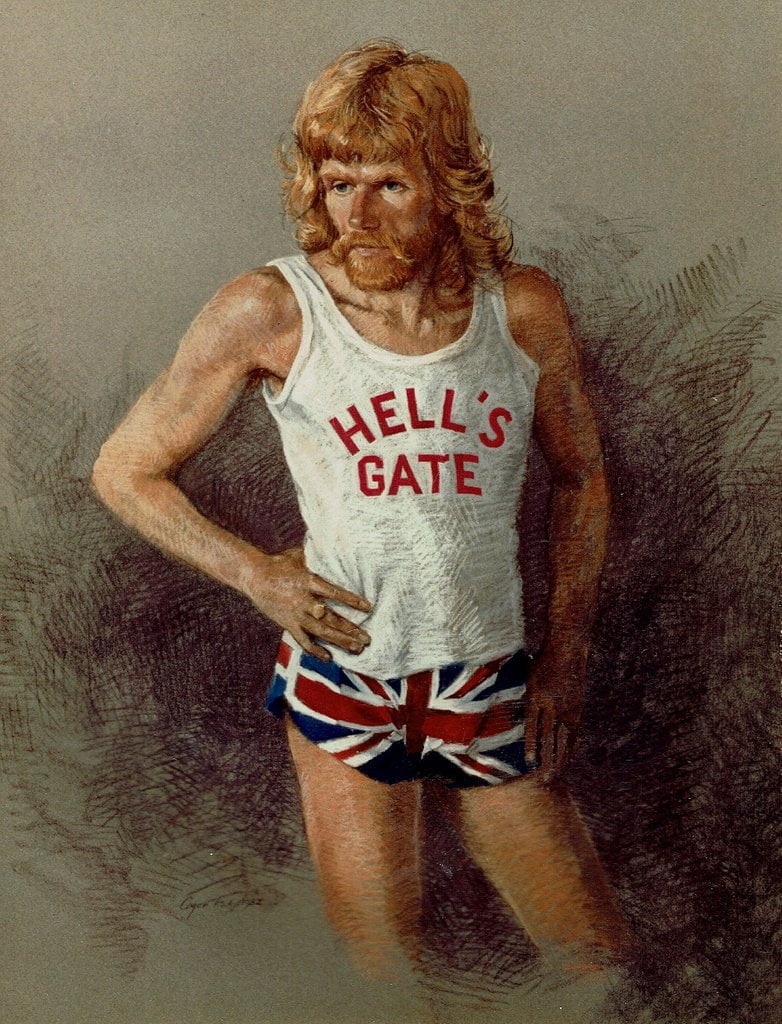

#791 The incomparable Al Howie

In Search of Al Howie

by Jared Beasley

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2019

$25.00 / 9781771603386

Reviewed by Timothy Lewis

*

The old adage tells us not to judge a book by its cover, but in the case of Jared Beasley’s In Search of Al Howie, one learns much from that practice. The reader’s eye is first drawn to the book’s bright yellow exterior. One’s curiosity is then piqued by the back cover’s relatively brief — but truly astounding — summation of Al Howie’s long-distance running feats and unusual personal history.

The old adage tells us not to judge a book by its cover, but in the case of Jared Beasley’s In Search of Al Howie, one learns much from that practice. The reader’s eye is first drawn to the book’s bright yellow exterior. One’s curiosity is then piqued by the back cover’s relatively brief — but truly astounding — summation of Al Howie’s long-distance running feats and unusual personal history.

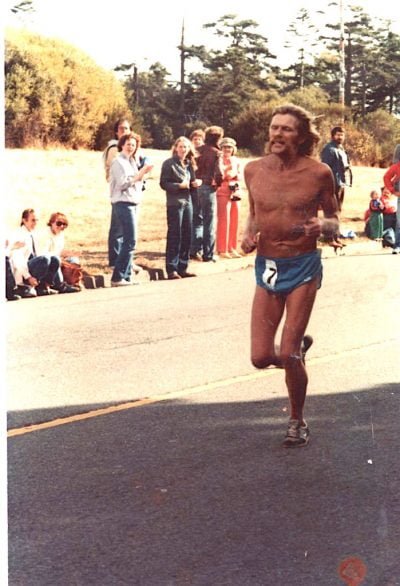

If you ran 2225 kilometres from Winnipeg, Manitoba, to Ottawa, Ontario, you’d be crazy. If the day after you arrived in Ottawa you showed up to a 24-hour race and started knocking back beers, you would be stupid. If you then ran the 195 kilometre, 24-hour race, won it, and ran all the way back to Winnipeg, you’d be a true freak of nature. If later, at 46 years old, you ran 7200 kilometres across Canada in the world-record time of 72 days, 10 hours, and then followed it up two weeks later by breaking another world record (which happened to be your own) in the longest certified race on Earth, you’d be a mega-distance alien. In all of this, if you were forever broke, using fake names and aliases, teetering on the edge of sanity, and doing it all in racing flats, you’d be Al Howie.

The book’s front cover features only the letters in the title and the author’s name against the aforementioned stark yellow background. But superimposed within each letter is a portion of a single photograph of Howie in peak racing form. That partial picture signals what is to come inside, as much like the book itself, it presents a fascinating but ultimately incomplete look at Howie. Jared Beasley is conscious of that reality, and, by times, admits that his quest to shed full light on Al Howie the man/mega-distance runner was an impossible one. “Understanding Howie would be like catching him full stride…. Howie the man was like a drifting fog, always disappearing just before you could grab hold.” (p. 29). In Search of Al Howie is thus a most appropriate title and foreshadows what is to come.

As the world of extreme distance running is one most are unaware of – races are 50 plus miles in length and often cover such distances for multiple days — Beasley wisely begins In Search of Al Howie with a two-page overview on the admittedly rare pursuit (pp. 11-12). He then skillfully hooks the reader in with the story of where the idea for the book originated: his regular encounters in a New York City park with a mysterious character known only as “The Pirate.” A veteran of the extreme running community himself, The Pirate insisted that any book on the topic had to focus on the very best of the lot: Al Howie (pp. 13-17).

Chapter one begins with Beasley’s first encounter with Howie in a BC government care home, in 2014. By that time, the latter had been physically and emotionally incapacitated for more than a decade. With prodding from Beasley, Howie agrees to share his story, but only on his terms. Respecting Howie’s wish that Beasley focus primarily on Al’s record-setting run across Canada in 1991, the book is divided into seven parts each named for a province, or provinces, that Howie traversed in that year, beginning with Newfoundland and ending in British Columbia.[1] While each segment of the 1991 run is covered in the appropriately named portion of the book, each part also contains several chapters that present a more chronological telling of Howie’s life story from his birth in 1945 to his death in 2016. The dual format, which honours Howie’s wishes while still allowing Beasley to tell the story in the manner he prefers, works for the most part; but, by times, distracts attention from the already under-appreciated cross-Canada run that Howie was clearly most proud of.

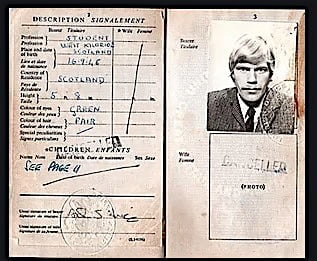

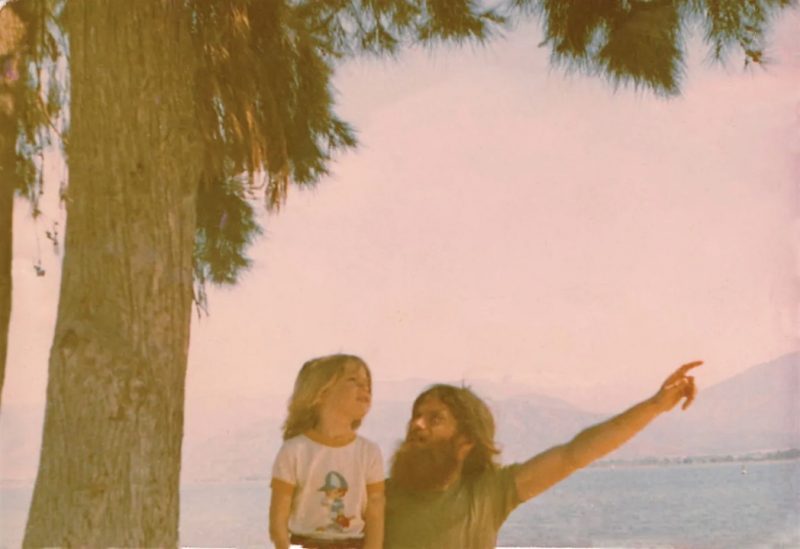

Appropriately enough given his atypical life story, we learn, early on, that Al Howie never existed. The man the world came to know by that name was born Arthur John Howie in Saltcoats, Scotland in 1945. Other than being born into a family with an unusual fondness for walking long distances, and having a mother who could be intensely introverted, there were few signs in Howie’s early years that he was destined for either extreme running greatness or significant mental health challenges. Indeed, into his mid-20s, Howie’s story comes across as one befitting the stereotypical Baby Boomer teen rebel. Intelligent, but unwilling to work in school, he took up a series of unskilled labour jobs, experimented with lots of drugs and alcohol, and, by age 22, somewhat reluctantly found himself a father and husband. Things took a more serious turn in 1972 when Howie left his heroin-addicted wife without warning, taking their young son Gabe with him (pp. 29-37). For the next year or more, Al smoked lots of weed while he and Gabe drifted with the Hippie scene across Europe and on to Turkey. Along the way, Al took up with a beautiful Canadian girl, and it was that relationship that brought Al and Gabe to Canada, Toronto in particular (pp. 39-55).

While he hated its cold winters, and lived for a time under an assumed name, due to his virtual kidnapping of Gabe, it was in Toronto where Al Howie first discovered his talent for distance running. Spontaneous running – upwards of 10 miles at a time – was the only thing that gave him peace of mind as his love life became more troubled. Then, with no proper training or footwear, he successfully took up a workmate’s challenge to run the 90-mile distance from Toronto to Niagara Falls in less than a day, finishing in 18 hours (pp. 60-68). Shortly thereafter, Al left Toronto and his girlfriend, relocating to British Columbia where economic security was often wanting, but Al’s running career began to flourish.

Howie, in fact, became consumed with running. It was all he focused on, so much so that Gabe frequently had to rely on strangers to provide him with food and shelter. Not surprisingly, the father-son relationship deteriorated over time, with Gabe eventually returning to the UK and never reconciling with Al. But while he clearly lacked parenting skills, the senior Howie was emerging as a distance running savant. After twice running the entire 360 mile length of Vancouver Island, the latter time in less than four days, Al Howie entered his first formal race: the 1979 Prince George to Boston Marathon. That race guaranteed the winner a place in the latter city’s more famous 26-mile event. Howie finished third. However, he came away inspired to train even harder after witnessing a one-legged Terry Fox push himself to complete the Prince George race and announce his intention to run across Canada to raise money for cancer. But no matter how hard he trained — running 200 miles a week on average — Howie, now in his mid-30s, found he did not have the speed required to be a top-level marathoner. What he did have was amazing stamina. He never tired, no matter how much he ran. He then entered his first 50-mile ultra race, and dominated the field. From there, the legend of Al Howie grew to astounding proportions, at least amongst those with knowledge of the niche sport of extreme distance running (pp. 73-80).

In typical Al Howie fashion, however, nothing about his newfound running success was conventional. He ran extreme distances not just during his races, but to and from them as well!

In July 1982, he ran from Calgary to Slave Lake, Alberta, 470 km, or 292 miles, and won the Slave Lake Riverboat Daze Marathon. He followed that by running back another 292 miles to Calgary, then another 500 miles back to Vancouver. He placed third, once again, in the Prince George to Boston Marathon, and after finishing the race, ran 510 miles back to Victoria to run the Victoria Marathon, where he won his age group (p. 83).

Even more perplexing was that Al Howie accomplished all of that using improper running shoes and on a diet that consisted almost solely of fast food and excessive amounts of alcohol! Yet, somehow, he consistently pulled off unfathomable running feats, including the more than 150 miles he covered in a single day at a 24 hour race in Ottawa, also in the summer of 1982. In time, a new marriage provided him with much-needed economic and social stability, as well as an improved diet and drinking habits, but he was also aging into his 40s. Thus as Beasley continues to document an ongoing array of Howie running accomplishments – the most impressive being world records, set in the early 1990s, for being the fastest to ever run 1000 km, 1000 miles, 2000 km, 1300 miles, and the 7295.5 km across Canada — the reader is left asking how this was possible? Contemporaries had similar questions; and Beasley notes in passing that Howie underwent testing at both UBC and the University of Victoria, but no details of those studies are revealed. The following passage is as close as Beasley comes to identifying Howie’s secrets of success.

Al was all legs and lungs. He stood a little over 5’8 and weighed in at 135 pounds. His rib cage was spread wide and was short relative to his long legs…. Yet his most powerful tool was his ability to live in his mind and keep himself distracted. This made him deadly at extreme distances…. (p. 86)

The other aspect of In Search of Al Howie that leaves one with unanswered questions is how the man in the title managed to be so likeable to so many people. The book introduces us to a number of individuals who either loved, or were genuinely fond of, Al Howie at all stages of his life, including his final years in government care. Yet this was also a man who proved incapable of either properly caring for his son, or maintaining romantic or familial relationships over the long-term. As elsewhere in his re-telling of Howie’s life, Jared Beasley provides some clues, but no complete answers. While Al was eccentric and non-conformist as a young man, those qualities, combined with his liberal experimentation with drugs and alcohol, made him a seamless fit in Hippie culture. His decent good looks and shy manner also drew women to him, especially once he had cute little Gabe in tow. Yet, in that same timeframe, he alienated, and/or withdrew from, those who knew him best, his family and first wife in particular. Nonetheless, Beasley concludes, somewhat mystically, that Howie “had a charisma that drew people into his world. Whether you were family, friends, or a stranger, even if you didn’t like him, you wanted to” (p. 49).

Al Howie’s world got ever smaller as time progressed, centred almost entirely on running, and his second wife believed he might have been autistic. But for a time at least, as in his Hippie days, he found a unique sub-culture where he felt at home; namely, the world of extreme distance running, which was populated by a good many others who did not fit societal norms (pp. 137-182). Toward the end of his life, however, Howie could find no place of comfort even within his own head. As Beasley notes, “[r]unning was how [Al] dealt with, not only his own demons, but the world and its problems” (p. 90). When he felt he could no longer run, the demons caught up to him.

The story of almost any athlete is one of rise and decline. And Al Howie’s sudden and unexpected arrival on the running scene was matched by an equally dramatic decline. In Howie’s case, however, that decline came not just in his physical ability, fuelled by undiagnosed diabetes and age-related injuries, but also his mental state. He became obsessed with the idea that he was dying, resisted insulin treatment, and fell into a deep depression-like state that doctors could not remedy and finally diagnosed as Singular Delusional Disorder. As Beasley pointedly writes: “Al was a one-off even in illness” (pp. 226-227). Howie spent the last decade and a half of his life sedated, in institutional care, lying facedown on his bed.

Al Howie’s story is one that richly deserved telling, and Jared Beasley does a commendable job in bringing it back to public attention. That he cannot, in the end, answer all the questions that arise from either Howie’s astounding athletic feats or his complex personal life is slightly unsatisfying, but totally understandable. As Beasley concludes, “Al Howie pushed his body and mind to the limits for reasons that are hard to grasp” (p. 235). Thus while In Search of Al Howie is not entirely fulfilling for either Beasley or his readers, most will conclude that it is a journey worth taking.

*

Timothy Lewis is Professor and Chair of History at Vancouver Island University in Nanaimo. Among the courses he teaches are several focused on the emergence and development of professional sports in Canada, and the place of hockey within Canadian identity. His research work is focused on the history of 19th and 20th-century New Brunswick, portions of which have been published in two articles in Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick have to share billing, as do Manitoba and Saskatchewan.