#779 The building goddess of Lund

The Way Home: How a Naïve Single Mom Built her House in the Forest

by Terry Faubert

Powell River: Steller Books, 2019

$15.00 / 9781096448211

The Way Home is available online through Amazon and Indigo, plus in Powell River at Coles and Ecoessentials, and in Lund at Pollen Sweaters. Terry Faubert can be contacted at tfaubert@secondflux.com

Reviewed by Kate Braid

*

In 1983, Terry Faubert was a small, skinny single mother, living in a rented house in Victoria, supporting herself and her five-year-old son, Jody, as a babysitter. But partly in hopes of finding a partner who wanted to live as she did in a wooded place, “camping forever,” she sets out to find a cheap — really cheap — piece of property where she’ll build a house so she and her son can live surrounded by trees.

In 1983, Terry Faubert was a small, skinny single mother, living in a rented house in Victoria, supporting herself and her five-year-old son, Jody, as a babysitter. But partly in hopes of finding a partner who wanted to live as she did in a wooded place, “camping forever,” she sets out to find a cheap — really cheap — piece of property where she’ll build a house so she and her son can live surrounded by trees.

Sound simple? In addition to being an adventure story, The Way Home reveals in a solid, straightforward narrative something about the attitudes of the early Eighties when there was a strong sense of the larger community, and simply showing up (including at the Healing and Survival Gatherings and communes Faubert visits in her search for land), proved you trustworthy.

She’s careful. Aiming to find three to five acres of land “far away from any town,” and knowing it unlikely her $1000 savings will buy property with a house on it, she buys a used van that can double as a temporary shelter. “I’d worry later,” she says, “about how to come up with a more permanent structure.”

The clarity of her ambition, and her determination, are what drive this memoir. She starts with an ad in the paper: “Single mom with 5-year-old son and cat hoping for a place in the country in Canada. If you have one to share, rent, or sell, please let me know.” When no one responds, she sets out with her son, in the van, and amazingly, finds the right acreage, near Lund, north of Powell River, for $18,000. After some intense bargaining, a loan from a friend, and working almost around the clock back in Victoria to make the down-payment, in July 1984 she and Jody move into an abandoned cabin on a property beside her own that a neighbour will let them use on condition she gets rid of it when she leaves.

My credibility was a little strained by the smoothness of the transition from the city to living in a broken-down cabin in deep woods with no running water, no heat, no telephone and no close neighbours. “Every peaceful day overflowed with beauty,” Faubert exclaims. “Each morning I awoke with joy.” Really?

But the real wonder of the story is Faubert’s commitment to making her project work — which she acknowledges simply as a result of being “stubborn.” For example, she first needs a road to her building site, so when a neighbour suggests she might find an old one — now overgrown — by tracking the fast-growing alder, this five-foot, 91-pound woman buys a chain saw, gets the neighbour to show her how to use it, and begins clearing land until she has “a road full of stumps” and abundant piles of firewood. And while she waits for a skidder to clear the stumps, fells yet more trees around the site for what will become a vegetable garden with raised beds. Her later admission that she’s “getting stronger” from all this physical labour is surely an under-statement!

At the same time, Faubert is home-schooling her son, taking him into Lund once a week for group activities and exploring the local terrain, plus dealing with survival issues like how to collect water from a deep pit nearby where neighbours assure her the water is potable — though she lives in fear of falling in with no way to get out, each time she lowers her bucket.

It’s a thin book — 150 pages in large font — and it could have used a lot more detail, like a casual reference to “mixing and pouring concrete.” What? How did she do that? Another neighbour? But she doesn’t say. And who and how far away were those neighbours who become vital to the success of her project? Clearly, some of them have kids too, because son Jody soon has “six new friends.” And the Goddess of Cheeky Women was surely watching over Terry Faubert because there are wonderful coincidences that help make her project possible. For example, another neighbour gives her a cast iron cooking stove and as she struggles to fit the new stove pipe, hikers passing by stop to ask directions and within minutes, fit the pipe for her. This, after weeks of no visitors. Someone else drops off a load of firewood. Thank you, Goddess. Thank you, neighbours.

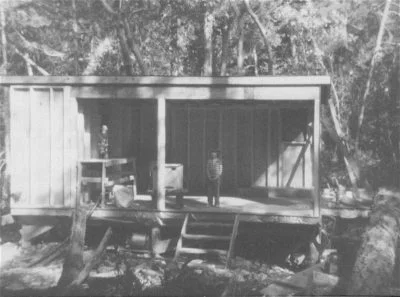

She’s not foolish. After the first winter — an early and very cold one — in a cabin with no electricity, no running water, no telephone, no insulation, bare plywood walls and a wet wood supply, February is spent with her parents in their heated house in Ontario. But when she and Jody return, Faubert has decided it’s time to build themselves a real house. Now the story becomes jaw-dropping. Another neighbour sells her a small pre-fab structure but she must move it onto her own property. So — alone, with no training and only a few borrowed hand tools — Faubert takes apart the house, one nail at a time. It’s an extraordinary story, taking extraordinary determination (not to mention strength and hard work) and as a carpenter myself, I wanted far more detail. But all we’re told is that “it was fun, like playing a game.”

Faubert does admit that the “neighbours rolled their eyes” at her plans to move and reassemble, first, this pre-fab house, then the old log cabin she and her son were currently living in. But as she states, “I stubbornly pushed ahead.”

The actual reassembling of the two structures, and putting on the roof, is a feat. This woman takes on jobs for which most jobs require a crane, or at least, two skilled carpenters. Again, the Goddess sends by neighbours and for a while, a boyfriend, who at crucial times are there to help her. By this point, I’d begun to wonder about the neighbours. Faubert says little, but I’m assuming the local men — it’s almost entirely men who come by — are more than curious. “Incredulous” is surely more appropriate, and they generously pitch in to help.

But clearly, it’s Faubert’s ingenuity and refusal to be stopped by mere “things” that gets this job done. And she doesn’t just trust to coincidence. When it comes to raising walls and the roof, she admits the need for help and puts up signs along the road announcing a “House-raising party” and sure enough, various locals turn up over the next few days, tools in hand, to help produce a finished (enough) main floor.

But moving the pre-fab is only half the job. Now she has to dismantle, board by board, the old cabin where she and her son had been living, to add this as a living room onto the new house deck. And because she doesn’t know how to build, she develops an ingenious and labour-intensive plan; she labels each board and transcribes it onto a diagram — a sort of blueprint? — that shows where it will have to be re-attached. Taking down a recently built pre-fab house, she admits, was one thing, but taking apart an old wooden cabin that has rotted and settled over decades, was something else. As she points out, “I was in for a rude awakening.” Here we get a little more of the nitty-gritty of hard physical work, including the appearance of the odd wandering bear. But eventually, following her own diagram, she attaches old house to new, “like fitting a giant three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle back together.”

There’s more dazzling ingenuity as Faubert starts to build the roof, first tracing angles from old rafters onto new and cutting them — with what kind of saw, she doesn’t say. Then, “with great difficulty” — which must be an understatement because again, it’s a job for at least two people – she raises and nails most of the rafters above her head. Again, friends and neighbours come to help finish the job and soon the roof is up and sheathed in plywood. “Explaining my process,” she says matter-of-factly, “only had them shaking their heads.” It reminded me how I once told fellow-framers that framing a house was a lot like sewing — and the incredulous looks I got.

When she needs cedar roofing shakes, she makes her own using a borrowed froe, from cedar rounds left after clearing the site. She hires someone to apply plywood and shingles to the roof, and paints the floor of her new house from a “partially used can I had come across somewhere,” in a shade that turns out “distinctly purplish” rather than the expected brown. And it’s done.

Later she’ll find the partner she’d first hoped for and they’ll add the luxuries of a drilled well, a generator, real plumbing and propane, and she’ll have three more children. But in September 1985, one year after she started her search for land, Terry Faubert and her son move into their new house, just in time for Jody’s eighth birthday party. And though readers may be left with many questions, most of us will be cheering.

*

In 1976 Kate Braid did a somewhat similar move to Terry Faubert’s, moving (alone) into an old cabin on the Gulf Islands. It was there she got her first job in construction, not alone, but under the tutelage of skilled carpenters. She went on to get her apprenticeship papers in Vancouver and work for 15 years as a carpenter, contractor and trades instructor in BC and the Yukon. Later she wrote about it, including two books of poetry and a memoir, Journeywoman: Swinging a Hammer in a Man’s World. A book of reflections about that experience, Hammer and Nail, is forthcoming from Caitlin Press in Fall 2020. For more information see her website. For a review of her recent book of poetry, Elemental (Caitlin Press, 2018), by Chris Levenson, see The Ormsby Review (no. 349, Aug. 23, 2018). Kate Braid also contributed a review of The Mudgirls Manifesto to The Ormsby Review no. 343, Aug. 14, 2018).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster