#776 Five women at the edge of empire

Kelly Black reviews two books:

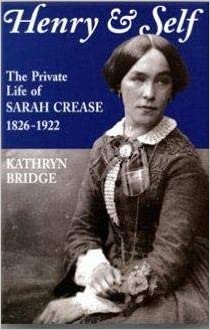

Henry & Self: An English Gentlewoman at the Edge of Empire

by Kathryn Bridge

Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum Press, 2019 (first published by Sono Nis Press, 1996)

$22.95 / 9780772672612

*

By Snowshoe, Buckboard and Steamer: Women of the British Columbia Frontier

by Kathryn Bridge

Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum Press, 2019 (first published by Sono Nis Press, 1998)

$19.95 / 9780772673107

*

When I first began reading Henry & Self: An English Gentlewoman at the Edge of Empire and By Snowshoe, Buckboard and Steamer: Women of the British Columbia Frontier by Kathryn Bridge, I was initially struck by the fact that the books are as much about archival records as they are about the settler-colonial women profiled. Certainly, this reflects Bridge’s training as an archivist and her notable career at the BC Archives and Royal BC Museum, where a majority of the records are kept. Henry & Self looks at Sarah Crease, while By Snowshoe, Buckboard and Steamer looks at Florence Agassiz Goodfellow, Eleanor Caroline Fellows, Helen Kate Woods, and Violet Emily Sillitoe. Both books are accessible to a general readership and provide historical analysis that works to understand these women in the context of their upbringing, class position, and the social and political life of colonial Vancouver Island and British Columbia.

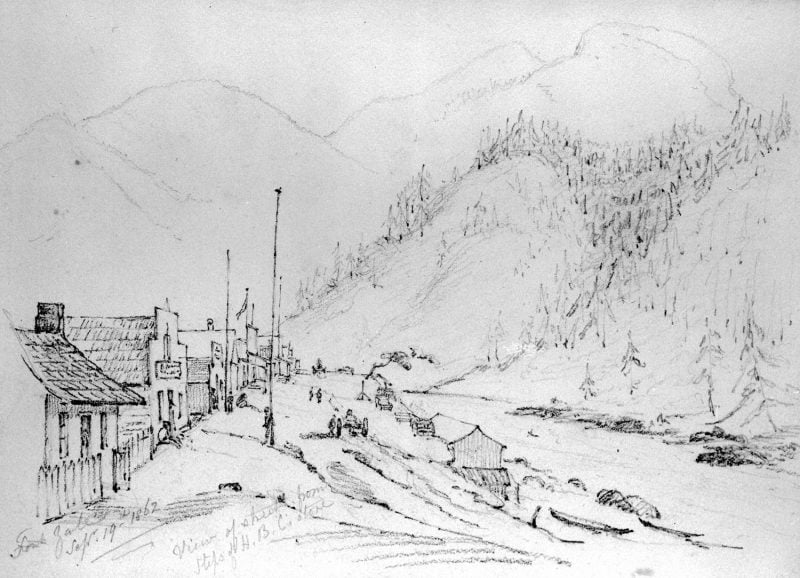

After a number of years apart, Sarah Crease joined her husband Henry in the Colony of Vancouver Island in 1860. Arriving at the age of 33, Sarah lived for the next 63 years in BC, leaving a wealth of archival documents, including correspondence, drawings, and paintings (Crease Family Fonds, PR-1344, BC Archives). By Snowshoe, Buckboard and Steamer draws more upon reminiscences written by the women profiled, for example, Florence Agassiz Goodfellow’s Memories of Pioneer Life in British Columbia.[1] But these are long out of print or never published, and in Bridge’s clear presentation they are brought from the shelves of the archives directly to the reader.

In both books, Bridge has let the records do much of the storytelling, as she explains:

It was important to me that Sarah’s story be told as much as possible in her own words. I wanted to use the records created by Sarah, and those of her female relatives, to tell the story…. The rich source of letters, sketches, and diaries housed in the BC Archives permits us to hear Sarah’s own voice (Henry & Self, p. 2).

Indeed, Henry & Self includes the entirety of Sarah’s 1880 journal documenting her travel with her husband (Henry Pering Pellew Crease, a judge on assize court circuit) through the Cariboo and Kamloops, a record that makes for a fascinating and now published primary source.

Through the writings and records of these women, Bridge offers important insights into early colonial life and families. A significant contribution of the books, especially Henry & Self, is Bridge’s ability to uncover what life was like for these women and their families before they became settler colonists. When reading and writing BC history, we may forget that many colonial settlers were fully formed humans before they arrived, bringing with them a breadth of life experiences that shaped their perspectives and actions.

While women are the focus of these books, the records also reveal a great deal of information about the actions of the men surrounding them. Their investments — often failed — and their efforts to establish lives and careers in the two west coast colonies determined much of their families’ experiences. The political economy of colonial life is omnipresent in these books, as are details about how social circles functioned in the old country and the new, particularly when it came to employment, housing, and marriage.

The deep knowledge of the archives that Bridge brings to the books also reveals many parallels with other colonial families. While reading, I found myself drawing links to my own work as director of Point Ellice House Museum and Gardens. The O’Reilly family called Point Ellice their home for 108 years, and Bridge’s description of the Crease children could just as easily describe the O’Reilly children, Frank, Kathleen, and Arthur:

Susan, Josephine, and Lindley remained at home throughout their adult lives. Most of their friends did marry, and the Crease daughters remained close to these friends, visiting and entertaining as before, and at times acting as godparents to the next generation of children (Henry & Self, p. 108).

Like their Crease family friends, the O’Reillys left behind a significant collection of records (O’Reilly Family Fonds, MS-2894, BC Archives). That similar monographs on the O’Reillys do not exist suggests that much work is still to be done.

Both books are reprints from Sono Nis Press; Henry & Self was first published in 1996, By Snowshoe, Buckboard and Steamer in 1998. I was left searching through them for a new preface or some other indication of what, if anything, has changed since they were first published. They both include only a short paragraph to help in this, entitled “Acknowledgments.” As these editions are essentially unchanged, I would argue that Adele Perry’s 1999 review of these books (and another by Cathy Converse) in BC Studies remains to the point:

At their best, both Bridge and Converse suggest that women were more than hardy pioneers or province builders: they were members of races, of classes, of families, and of communities; they had sexual identities and political positions. Historians need to go beyond inscribing women into existing narratives of BC history and, instead, to critically analyze how gender worked to structure and shape society. It is only then that we will be able not only to acknowledge women’s existence, but to use that acknowledgment to begin a fundamental and much needed reconsideration of British Columbia’s past.[2]

Part of Perry’s reconsideration includes understanding settler-colonial women’s roles in shaping the dispossession of First Nations. Other more recent scholars have explored this topic. Writing about nineteenth century British family correspondence, historian Laura Ishiguro argues that, while “individuals differed in their explicit support for colonialism, the state, and white supremacy, British Columbia’s developing settler structures enabled and encouraged their lives there.”[3] Bridge does show that settler-colonial women did not always share the same prejudiced beliefs about race and class (see for example her discussion of Helen Kate Woods or Eleanor Caroline Fellows in By Snowshoe, Buckboard and Steamer), but a new preface might have drawn attention to recent scholarship on British families, empire, and settler colonialism, and cited the work of scholars such as Perry and Ishiguro.

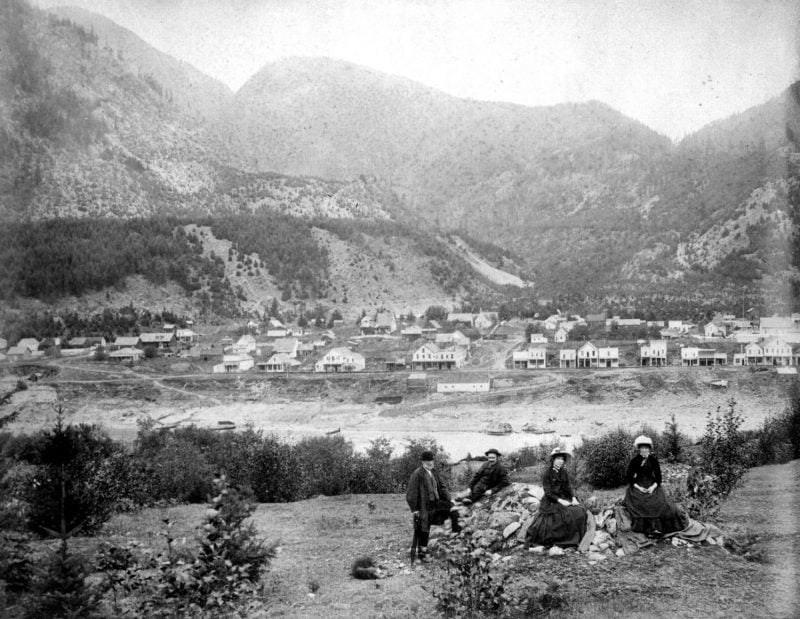

Both books are richly illustrated with sketches, drawings, paintings, and photographs. Given that these reproductions come from the Royal BC Museum and BC Archives (RBCM&A), I’m confident in stating that no publisher other than the Royal BC Museum could have re-issued these books. Readers of the Ormsby Review may be aware that BC authors, publishers, and non-profit societies continue to raise concerns about the steep costs associated with the licensing and reproduction of materials from the RBCM&A.

Take, for example, the costs potentially associated with Henry & Self, which includes 48 illustrations and 52 photographs. The BC Archives licensing and reproduction fee schedule (as of March 1, 2020) lists the costs of licensing for books with a print run of up to 3,000 copies at $50.00 per image, and for a print run of 3,000 to 5,000 copies, at $100.00 per image! These figures do not include costs associated with the cover image or reproduction of materials not already digitized by the institution.

Thus, the total cost to licence and reproduce materials for Henry & Self would normally be between $5,000 and $10,000. Authors often have licensing and reproduction costs downloaded to them by their publisher. How many BC history authors can afford to create this kind of richly illustrated and in-depth monograph? This question raises profound concerns about the kind of work that is, or is not, being done with the rich and significant public collections held at the Royal BC Museum and Archives. That readers are being given reprints instead of new or updated research on women and families found in the BC Archives may also speak to changing priorities in publishing or reduced institutional budgets.

Still, Henry & Self and By Snowshoe, Buckboard and Steamer remain engaging, readable, and pertinent works on subjects that require our attention, and it is clear that Bridge spent many hours with the archival collections she draws from, a fact that shines through in her writing, analysis, and choice of artwork and photographs. I eagerly anticipate her next work of BC history that so explicitly and intimately connects its subjects to the archival records it draws from.

*

Kelly Black is Executive Director of Point Ellice House Museum and Gardens in Victoria. He is also President of the Friends of the BC Archives and an adjunct professor in the Department of History, Vancouver Island University, Nanaimo.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] See Florence Goodfellow, Memories of Pioneer Life in British Columbia: A Short History of the Agassiz Family (Canyon Press, 1982; first published 1945).

[2] See Adele Perry’s review essay, “Writing Women into British Columbia History,” BC Studies 122 (Summer 1999), pp. 85-88; 88.

[3] Laura Ishiguro, Nothing to Write Home About: British Family Correspondence and the Settler Colonial Everyday in British Columbia (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019), p. 18, reviewed by Robert Hogg in The Ormsby Review, no. 661 (November 19, 2019).

One comment on “#776 Five women at the edge of empire”

Bravo, Kelly, for your advocacy in asking for reasonable rates for BC Archives images. As a former Museum administrator has pointed out, most of the photographs were freely donated to the Archives, so why the high cost? I used images from the NAC for my book, and just received the following e-mail from the Canadian Museum of History: “Our usual costs for high resolution digital files is $15 CAD each and an admin fee of $10. Permission costs are calculated based on the details of your project.” Thank you! Marie Elliott, Victoria and Mayne Island