#773 Past imperfect

Agency

by William Gibson

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (Berkley Books), 2020

$37.00 / 9781101986936

Reviewed by John Belshaw

*

Fully articulated alternative histories have been around for at least a century. In addition to attempts on the part of scholarly historians to change up the past, there are plenty of storylines in fiction that put a protagonist into a puzzling, often terrifyingly different timeline. In film, literature, and other media, we are regularly shown a present in which things are familiar and yet not. (It’s a Wonderful Life comes to mind as a personal counter-history, while The Man in the High Castle is only one of many works which posit an Axis victory in 1945.) Broadly defined, “para-history” constitutes a sub-genre in its own right, one with deep science fiction roots. These are not Wellsian voyages to the future: they imagine a change in our past that produces our new future or a chance to observe (or take advantage of) a parallel timeline.

Fully articulated alternative histories have been around for at least a century. In addition to attempts on the part of scholarly historians to change up the past, there are plenty of storylines in fiction that put a protagonist into a puzzling, often terrifyingly different timeline. In film, literature, and other media, we are regularly shown a present in which things are familiar and yet not. (It’s a Wonderful Life comes to mind as a personal counter-history, while The Man in the High Castle is only one of many works which posit an Axis victory in 1945.) Broadly defined, “para-history” constitutes a sub-genre in its own right, one with deep science fiction roots. These are not Wellsian voyages to the future: they imagine a change in our past that produces our new future or a chance to observe (or take advantage of) a parallel timeline.

William Gibson does something significantly different. Yes, he shows us a future, about 150 years from now. We (you, me, us) arrive there the hard way through pandemics and other bad stuff that the (mostly very well-off) survivors refer to as “the jackpot.” This being Gibson’s vision, the technology of the future is impressive, slick, and squishy. To be clear, there has been no change in history to produce this world: 9/11 still happened, Hitler is still dead. The wrinkle in time is that folks in the future have been alerted to a malicious change back in 2015, one that doesn’t impact their world, but which creates a spur-line or “stub” in which the locals — in 2017 — are now in serious jeopardy.

Some future Londoners arrange to interfere helpfully in this stub to ensure that its people avoid the nastiest of possible outcomes: a nuclear war. Otherwise, as one character in the future explains to Verity, an “app whisperer” in the stub version of 2017, “our idea of apocalypse would be the least of your worries. Unless you get a nuclear winter to reverse the warming, and we had people seriously floating the idea of trying that.” Sure there’s a different political landscape (“Remain” won in Britain; Trump lost in 2016) but otherwise things end in tears: “…as far as we know you’ll have the rest coming your way, if you don’t blow yourself up” (p. 270). So there you have it. The stakes are high: first prize is a future of pandemics, kleptocratic regimes, and unrelenting climate decline; second prize is all of that but also an inferno.

This makes the motivations of Wilf Netherton and his colleagues in future London a little opaque. If people in a stub don’t know any better, then why not leave them to it? Either way, they fry or they die. To be fair, this is moral ground Gibson visited in his 2014 The Peripheral. That novel introduces Wilf, his partner Rainey, and some shadowy figures with fearsome influence, and it lays the groundwork for Agency. In The Peripheral there’s another, separate stub referred to as “the county,” where some residents know that they’ve departed from the mainstream timeline. As well, they know they’ve been spared disaster by technologically advanced people from a future they’ll never live to see. Rainey, at least, finds this disturbing and makes the point to her husband.

“I liked the county,” she said, “even though it made me sad.”

“It did? Why?”

“They’re living in a conspiracy theory, but a real one. Controlled by secret masters.”

“But isn’t it better there now, than if we hadn’t intervened?” he asked.

“It is, I’m sure, but it makes a joke of their lives.”

“But everyone you know there is on it.”

“I don’t know whether I’d rather know or not know.”

Which brings me back to Wilf’s life with Rainey and their infant child and to the lives of their contemporaries who have the “connectivity” necessary to mentor and meddle in deviating timelines. They’re nuthin’ special: they still have to do a lot of the banal stuff like change nappies, make dinner, avoid bores, etc. Considered as a whole, however, they’re not a much wiser, evolved, and slightly godlike update of us. They’re venal, suspicious, untidy, lazy, entitled, brooding, self-obsessed and narcissistic, egotistical, cruel, and utterly capable of making mistakes over and over again. So, their meddling in the stubs invites some obvious moral questions, the obvious one being: isn’t the path to Hell paved with good intentions?

The Peripheral and Agency may be two-thirds of a trilogy, but the writing is remarkably different. While the former is a blast-furnace of Gibson’s cyber-language, the latter is relatively more immediate, grounded, and more tactile. Everyday objects and acts are described with loving detail. In a café in 2017, Verity watches “the boy behind the counter tong [her breakfast] onto a white china plate. He put the plate on a Soviet-looking plastic tray … then added her mug of coffee, plus tableware rolled in a paper napkin” (p. 40). Smells and temperature changes get a good workout in Agency. Paragraphs are briefer, tighter and the world is thrown into sharper relief.

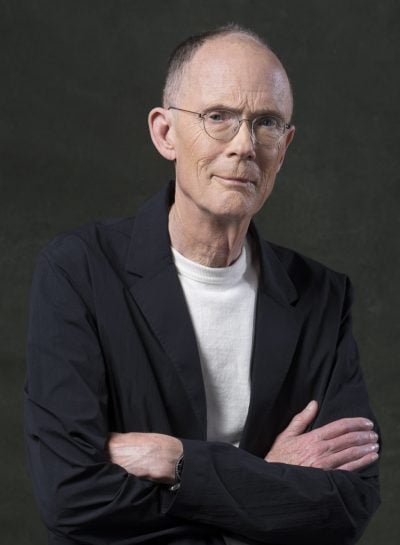

I suspect this change in style serves a particular purpose, though Gibson might disagree. At a recent Q&A hosted by the Vancouver Writers Fest, Gibson leaned hard into the organic and spontaneous nature of his process. The characters themselves make choices; Gibson writes as if from the sidelines. There’s a flow, he claims, that arises of its own volition. This frankly “aw, shucks” posture doesn’t wash with me: I think Gibson’s a clever writer and that he’s accomplished a nice trick here that might be more cunning than cyberpunk.

It does little to spoil the story to tell you that “Eunice,” the character truly at the heart of this novel is not human. She is a very advanced piece of artificial intelligence (AI), one who is finding her way from the servant role for which she was designed to one in which she has agency. The characters in this novel are well drawn but none so tenderly as Eunice. She’s a child but she’s also a saucy adult. She’s emerging but she’s doing so fully grown. The reader can’t help but care about Eunice and be saddened when she blips out of the narrative and very pleased when she blips back in. There was something about this relationship between the reader and these characters that reminded me of the old radio program, The Shadow. It was an action-packed drama involving … voices. You can’t see anyone in the program because, well, it’s radio, but there was one character who was more invisible than all the others. And the wonder of it was that the listener believed that, in a room full of invisible people, there was someone else present whom none of us could see. Agency performs a similar sleight of hand. While we have to imagine Verity, Rainey, Wilf, Grim Tim, and all the other real characters, there’s this other character, Eunice, whom we have to imagine even harder. Gibson’s attention to details about their bodies, clothes, food, and environment enables us to picture the humans: he loads us up with minutiae about them so that our brain can be hyperalert to her.

The fact that one feels the greatest emotional attachment to the character of Eunice is testament to Gibson’s gift as a storyteller first … and as a visionary second.

*

John Douglas Belshaw, Ph.D., FRHistS, is a history professor at Thompson Rivers University — Open Learning. Among other accomplishments, he is the co-author, with his colleague and spouse Diane Purvey, of Vancouver Noir: 1930-1960 (Anvil, 2011) and the editor of Vancouver Confidential (Anvil, 2014). John Belshaw makes his home in Vancouver’s East End where he does academic stuff and dabbles in fiction.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster