#771 A tale of rubble and splendour

Lampedusa

by Steven Price

Toronto: Penguin Random House (McClelland & Stewart), 2019

$32.00 / 9780771071683

Reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy

*

From its jacket photo, which rivets the eye to the top of a stunning gilded inner courtyard in Rome, even as that sky is blocked from the reader, to the epilogue and to the narrative proper, Steven Price’s third novel and 2019 Giller Prize and 2020 BC and Yukon Book Prize finalist, Lampedusa is a rich, layered experience. The final years of Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, the last prince of Lampedusa, Italy’s most southern island and part of the Sicilian province of Agrigento (on which, like all of his regal predecessors, he has never set foot) are fertile grounds for imagination. Price’s fictionalization of the period during which Guiseppe wrote a novel about the decline of the aristocracy is equally devoted to the process of writing, the relationship between one’s past (personal and familial) and who one is in the present, the tenderness of personal relationships, and the vagaries of personal eminence. Lampedusa is above all an homage to literature. We would be hard pressed to find a more rewarding read; Price is a master of both revelation and concealment – and at knowing when each is called for.

From its jacket photo, which rivets the eye to the top of a stunning gilded inner courtyard in Rome, even as that sky is blocked from the reader, to the epilogue and to the narrative proper, Steven Price’s third novel and 2019 Giller Prize and 2020 BC and Yukon Book Prize finalist, Lampedusa is a rich, layered experience. The final years of Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, the last prince of Lampedusa, Italy’s most southern island and part of the Sicilian province of Agrigento (on which, like all of his regal predecessors, he has never set foot) are fertile grounds for imagination. Price’s fictionalization of the period during which Guiseppe wrote a novel about the decline of the aristocracy is equally devoted to the process of writing, the relationship between one’s past (personal and familial) and who one is in the present, the tenderness of personal relationships, and the vagaries of personal eminence. Lampedusa is above all an homage to literature. We would be hard pressed to find a more rewarding read; Price is a master of both revelation and concealment – and at knowing when each is called for.

On a January day in 1955, Giuseppe learns he has a disease that will likely soon kill him, particularly if he continues to smoke. The fifty-eight-year-old aristocrat continues to smoke, delays informing his wife of his diagnosis, and lives out his days in reduced circumstances in Palermo with that wife, renowned Latvian psychoanalyst Alessandra (Licy) Wolff, in half of a palazzo that has been seriously damaged by World War Two bombing — his ancestral home, hauntingly just several blocks away on Via Lampedusa, having been annihilated by the Americans in the same way in 1943. As you might expect, Lampedusa explores the personal pasts of Guiseppe and Licy against the backdrop of socio-political degeneration.

Given the rich cultural life of the couple in the novel’s present time, readers might be forgiven for forgetting that they live amidst rubble and without running water. Café life is stimulating — a platform for rewarding discussion and debate. Short trips are frequent, and relationships with relatives plentiful. Bibliophile Tomasi is entrenched in the works of Stendhal, as well as a variety of British writers, to the point that he is an informal tutor to a small group of aspiring academics. Their social circle is full.

Particularly compelling is the tender relationship of the couple with bright young minds Gioacchino (“Gio,” a cousin of Lampedusi) and Orlando, with whom Giuseppe connects at a bookseller. As he lectures them on English literature, he becomes for them a link to the past; likewise they, with their modern ways, educate him about contemporary art. Gioacchino eventually takes on a musically talented girlfriend, Mirelle, and the two couples grow closer — to the extent that the younger couple provides a prism through which he recollects his budding romance with Licy, as well as transport and care for the ailing Giuseppe. The older couple symbolically transcend their childlessness by legally adopting Gio (with the approval of his parents). Respect and understanding are at the crux of this intergenerational relationship; reverence for arts and education fosters it.

Guiseppe’s long-held notion to write a novel about the decline of the Sicilian aristocracy, focusing on the 19th century movement for Italian unification — the Risorgimento — that led to the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, takes on new urgency upon his diagnosis. That endeavour necessitates reflection on his personal history, and here Price deftly juxtaposes both the political and the personal and past and present. Particularly affecting is the detail in which the protagonist’s maternal lineage is evoked: the dramatic death of his mother’s favourite sister at the hands of a cavalry officer, preceded by the death of another sister by starvation, resulted in a public and gruelling trial in Rome that affected the youngest sister so much that she committed suicide. Not only was Guiseppe’s mother changed forever by these tragedies; so, too, he now recognizes, was he. The public and the private worlds mesh grippingly.

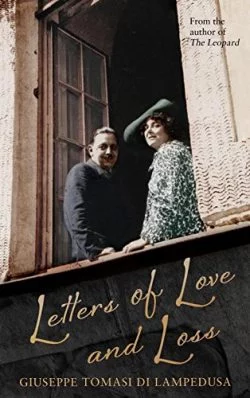

From its romantic beginnings — sparked by Licy’s beauty and fierce intellect — in London in 1925, through repeated personal and financial loses, the couple’s relationship has evolved into a rather subdued and not outwardly particularly communicative one, as they have separate bedrooms, and Licy sees patients most evenings. However, theirs is a mature connection: one in which words are not always necessary or even advisable, as a deep understanding through shared lived experiences underpins it. When Guiseppe eventually informs Licy of his illness, after her initial devastation, she is movingly loyal and affectionate. Perhaps as significantly, she is steadfast in her belief that his novel is a masterpiece, acting as both consultant and supporter.

In Lampedusa, the past is always erasing, even as it re-inscribes itself in the present in fading yet indelible font. As he writes about the dying of the prince, Giuseppe recognizes more than faint echoes in his own life: “he had watched the sweet world of the belle époque vanish….Truly vanish. He knew: because everything had changed, changed utterly, so that his childhood no longer seemed admirable, or even worth recovering, if such a thing were possible” (p. 233). Price evokes sadness and loss beautifully.

Although not without his doubts about the merits of his novel, Lampedusa dedicates himself to its completion, despite increasing pain and frailty, revising it until he is able to use familial literary contacts to get the manuscript in the hands of a publisher. However, he would see only rejection — by two publishers — before his death in July of 1957. He meets this failure resignedly yet philosophically, putting it into his life’s context:

It saddened him to think the novel might not be published and so immense was his sorrow that he could not look at it directly, only sidelong, like a man regarding a letter he did not wish to open. And that is how, he understood, he had looked at life for almost his entire duration on this earth. Could he have lived differently? It did not matter now (p. 299).

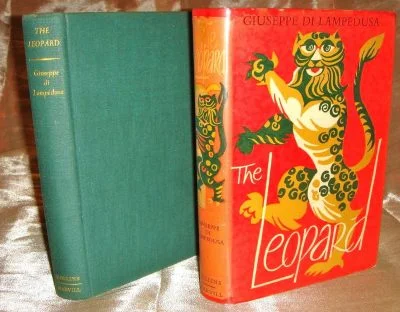

Lampedusa’s final chapter moves ahead to 2003, when Gioacchino, now superintendent of the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, is preparing for an interview with a representative of an American film company about the rerelease of Luchino Viscounti’s The Leopard — based on Lampedusa’s novel, published in 1958, which went on to become the all-time best-selling novel in Italy, and was widely acclaimed as a masterpiece. Through the eyes of his son, we get differently filtered commentary and a neat but not heavy-handed summation of the character of the last prince of Lampedusa. For example, Gio decides Giuseppe’s point of view of the Risorgimento was coloured by his loss and the fact that he wasn’t willing to die for a political cause, and that his novel was both “a projection of the author’s desire” and a cautionary tale – warning subsequent generations of Italians not to repeat his mistakes: the novel is as much about Giuseppe Tomasi de Lampedusa as it is about the Risorgimento (p. 321).

We also learn that her husband’s death left Licy bereft for the rest of her life — isolating herself, she became defensive and sharp tongued, scrupulously editing her late husband’s private papers to protect his reputation. Much of the tender contents of a farewell letter to Gioacchino that remained hidden inside a book in the family library until it was discovered in 2000 are quoted in this chapter. Now older than his adopted father was when he died, Gio is brought face-to-face not only with depths in their relationship his younger self had been unaware of, but also with his own artistic choices and mortality.

Steven Price’s graceful, writerly style could not be better fitted to the subject matter and time period he is reflecting. Through a third-person narrator, he steeps the thoughts and actions of Giuseppe di Lampedusa in old-world tradition while evoking meditation on the creative process, the power of art, mortality, and the circumstances and relationships that make up a life.

That fiction is especially rewarding that leads readers to more art — and here I am thrice blessed: not only did Lampedusa point me to Bulgarian photojournalist Seth Vane’s “Tunnels to the Sky Series” and other of his dazzling works; it has also put Price’s Into That Darkness and By Gaslight at the top of my “Must Read” list — right beside The Leopard.

*

Ginny Ratsoy is an Associate Professor of English at Thompson Rivers University specializing in Canadian literature. Recent courses have included Literature of the BC Interior and The Environment in Canadian Literature. She has published articles on theatre, playwrights, and small cities in British Columbia, and edited books, including Playing the Pacific Province: An Anthology of British Columbia Plays, 1967-2000 (Playwrights Canada Press, 2001, co-edited with James Hoffman); Theatre in British Columbia (Playwrights Canada Press, 2006); and, with W.F. Garrett-Petts and James Hoffman, Whose Culture Is It, Anyway? Community Engagement in Small Cities (New Star Books, 2014). Her latest academic publication is about a wonderful third-age learning organization, The Kamloops Adult Learners Society, in No Straight Lines: Local Leadership and the Path from Government to Government in Small Cities, edited by Terry Kading (University of Calgary Press, 2018); see Michael Lait’s review in The Ormsby Review no. 473 (January 27, 2019). For The Ormsby Review she has recently reviewed books by Sarah Butler, Don Hunter, Jack Hodgins, and others.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#771 A tale of rubble and splendour”