#754 Hurt & healing at Prophet River

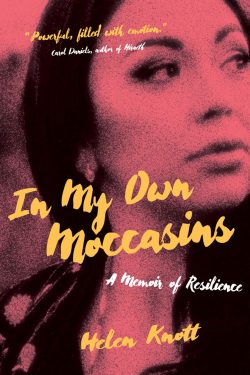

In My Own Moccasins: A Memoir of Resilience

by Helen Knott

Regina: University of Regina Press, 2019

$24.95 / 9780889776449

Reviewed by Angie Tucker

*

Of Dane-Zaa (previously the Beaver people), Nehiyawak (Cree), and Métis ancestry, Helen Knott is a writer, poet, and Indigenous land rights activist from the Prophet River First Nation, situated between Fort Nelson and Fort St. John in northern British Columbia. She has a BA in Social Work from the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George, where she is now a graduate student in First Nations Studies.

Helen Knott has figured in two books covered in The Ormsby Review: Breaching the Peace: The Site C Dam and a Valley’s Stand against Big Hydro, by Sarah Cox, reviewed by Jonathan Peyton in The Ormsby Review No. 327 (June 22, 2018); and she is the subject of an essay by Andrew MacLeod in Damming the Peace: The Hidden Costs of the Site C Dam, edited by Wendy Holm and reviewed by John Gellard in The Ormsby Review No. 353 (August 26, 2018).

Helen Knott’s narrative, In My Own Moccasins: A Memoir of Resilience, reviewed here by Angie Tucker, was one of 12 books long-listed for the RBC Taylor Prize in December 2019 – Ed.

*

Throughout In My Own Moccasins, Helen Knott writes poetically that healing is grounded in remembering and that remembering is medicine for Indigenous women. She writes from a vulnerable space as she continues her own healing journey and provides a voice of resilience, pride, and strength for Indigenous women with similar experiences.

Throughout In My Own Moccasins, Helen Knott writes poetically that healing is grounded in remembering and that remembering is medicine for Indigenous women. She writes from a vulnerable space as she continues her own healing journey and provides a voice of resilience, pride, and strength for Indigenous women with similar experiences.

As I read its pages I heard the voice of a girl lost in a world without pride in herself. I heard not just the voices of her life’s journey, but the voices of countless others. With the awareness of generations of Indigenous women and girls murdered and missing at wholly disproportionate rates, In My Own Moccasins provides an important window into Indigenous women’s experience. It presents an opening to consider how some Indigenous peoples have moved about in the world, oppressed within a racist colonized society that more often invisiblizes Indigenous bodies and experiences.

Knott describes clearly her experiences and feelings in an unflinching and relatable manner. A word of caution: In My Own Moccasins begins with a content warning: “This memoir has content related to addiction and sexual violence. It is sometimes graphic and can be triggering for readers. If you are a survivor of sexualized violence, addiction, or intergenerational trauma and find yourself triggered, please be gentle with yourself.” Accordingly, it is sometimes difficult to read. If you have shared some of this history, these recollections may trigger past events. The first part of the book focuses on the fallout caused from intergenerational trauma including drug abuse, alcoholism, physical abuse, and the repercussions of sexual assault, while the latter half is about gaining strength and resilience through reconnection.

This is a story about Indigenous peoples in the present, sometimes stuck between rural and urban spaces and at the crossroads of living with traditional teachings, and without them. It is about Indigenous peoples finding a space to exist outside of romanticized depictions from the past. It is about them trying to find their place in the world today. It is about finding where they belong.

Through the recognition of what happened in the past with residential schooling, poverty, illiteracy, incarceration, violence, the shame of being Indigenous, and becoming “lost,” Knott realizes through her family’s experiences that she always came from a place of resistance and strength (p. 173).

Rather than continue to focus on the weaknesses of the past, she tunes in to the strengths she has gained through family, community, and her own journey. She reconnects with ceremony and with Indigenous Elders. She reclaims her relationships with her other-than-human relations, especially Grandmother Moon and the Stars, who watched over her as she overcame her addictions. These reconnections to traditional Indigenous knowledges lead her to have pride in herself as a strong Indigenous woman. She is able to forgive herself for her past.

Most importantly, Knott is able to create boundaries to give her control of important situations in her life and work. In so doing, she becomes a voice for women who have been sexually abused or who have experienced violence. “Healing yourself is the ultimate act of resistance,” she writes. “Now go and reclaim that medicine” (pp. 296, 299).

*

Angie Tucker is Red River Métis from the Poplar Point/St. Anne’s area in Manitoba. An Indigenous feminist and cultural anthropologist, she is currently enrolled as a PhD student in the Department of Native Studies at the University of Alberta under the supervision of Dr. Adam Gaudry. Her Masters thesis, “awana niyanaan/Who Are We?” centred on the Buffalo Lake Métis Settlement in Alberta. In it, she sought to understand how attachments to traditional culture promote both self and group identity and to challenge the more often stringent definitions of what constitutes “being” Métis in legal, academic, and social understandings. Her doctoral work centres on Métis relationships to land and the revitalization of the Cree/Michif teaching of wahkohtowin as a basis to create a model for Métis inclusion. She promotes the use of equitable and inclusive land consultation agreements and processes that privilege Métis knowledge systems.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster