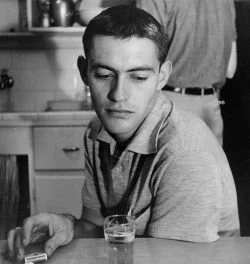

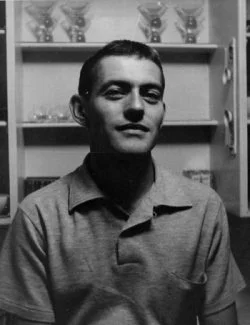

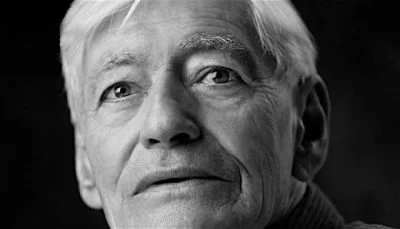

#749 Robin Blaser in retrospect

A Literary Biography of Robin Blaser: Mechanic of Splendor

by Miriam Nichols

New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019

$39.99 (U.S.) / 9783030183264

Reviewed by Sheldon Goldfarb

*

The most astonishing section of this book comes when author Miriam Nichols describes Robin Blaser’s time as a teacher at Simon Fraser University. Perhaps it is because Nichols was his student and has first-hand experience of the show Blaser put on with his courses on Arts in Context, drawing on the whole range of cultural history to explain poets like Emily Dickinson; but whatever it is, this section of the book truly stands out.

The most astonishing section of this book comes when author Miriam Nichols describes Robin Blaser’s time as a teacher at Simon Fraser University. Perhaps it is because Nichols was his student and has first-hand experience of the show Blaser put on with his courses on Arts in Context, drawing on the whole range of cultural history to explain poets like Emily Dickinson; but whatever it is, this section of the book truly stands out.

It even makes one think that maybe Blaser’s true calling was as a teacher, but according to Nichols, Blaser always insisted that he was a poet first, and indeed after only twenty years at SFU, he took early retirement to devote himself to his poetry.

What is also astonishing about this section halfway through the book is the realization that Blaser in many ways was a traditionalist. He emphasized the importance of knowing Homer, Virgil, Dante, and the Bible. The Bible is especially a surprise, because didn’t Blaser break with his childhood Catholicism? That’s what the early part of this biography would lead one to believe, and yet at the end there is Blaser calling himself an “aging Roman Catholic.”

Of course, if you take a look at Blaser’s poetry, it’s not like reading Robert Frost. He may have immersed himself in the tradition, but in the same way as James Joyce immersed himself in Greek myth and produced Ulysses. And Blaser was Joycean, a modernist, part of the postwar New American Poetry movement, part of its early flowering in Berkeley in the late 1940s.

Or was he? He hung out with one group of New American Poets, led by Jack Spicer and Robert Duncan, but in some ways he was not yet part of the group. He wrote a story at this time called “The Pacific Spectator,” satirizing the Berkeley scene and positioning himself as not quite a participant, more an observer, one suffering strain from the clash between his early Catholicism and the experimental ways he was discovering at university.

Nichols perhaps makes less of this than she might. One of her favourite expressions is “in retrospect,” and she keeps trying to show that the early, still Catholic Blaser writing poems about Jesus was just looking ahead to his less Catholic poems about non-Christian incarnation and other forms of sacredness.

Perhaps, but there is a certain flattening here, and one misses a depiction of a final break with his early views. At what point did the Catholic boy from Idaho become the experimental poet of Berkeley and San Francisco? And how?

It would be good to get more biographical information from this book, which strangely foregrounds its status as biography in its title but then devotes more time to literary analysis of Blaser’s works than to depicting the arc of his life.

And it is a heavily theoretical analysis that wanders away from Blaser at times to discuss Spicer or Duncan or Charles Olson, who wrote cryptic letters to Blaser telling him he lacked syntax. Nichols’ prose is sometimes cryptic too, appealing perhaps to contemporary literary theorists, but a bit offputting for the ordinary reader looking to find out how Blaser became Blaser.

And then there is the issue of postmodernism. Another surprise in the second half is to discover how critical Blaser was of postmodernist theory. He believed that language was a way of reaching out to the cosmos, of expressing experience, in opposition to postmodern theorists who questioned the very idea of experience. We learn this as we go along, but Nichols begins her book by saying Blaser made “a unique contribution to postmodern poetics.” I don’t know. It’s a bit like saying Marx made a unique contribution to capitalism.

But there’s some interesting material in the early pages, about Blaser having a difficult time growing up gay in mainstream America, about his horrific experience with a teacher who dismissed his poetry, perhaps causing the delay in his beginning to publish (though he was always a slow producer, creating a not very large oeuvre). Nichols interestingly describes him as a mixture of fragility and defiance, and it is also interesting to follow him through his boyhood imaginings, including his pretending that he was descended from the lost Dauphin of France.

One thing I wish Nichols had followed up is what seems like an interest in Samuel Johnson, the old Tory from the eighteenth century. When among and yet apart from the Berkeley poets, Blaser decided he would write something called “Lives of the Poets,” a title stolen from Johnson. Later in describing the clash between the imaginative world of the Berkeley poets and the more solid world of the actual university, Blaser said it reminded him of Dr. Johnson, alluding to the famous incident in which Johnson said he was refuting the notion that there was no reality by kicking a stone. (The notion belonged to Bishop Berkeley, by the way, after whom Berkeley, California was named, so Blaser may have been playing on various levels.)

And in this early anecdote can we not see the later Blaser? Holding onto the notion of reality in the face of the postmodernist onslaught? Perhaps, perhaps. In retrospect.

*

Sheldon Goldfarb is the author of The Hundred-Year Trek: A History of Student Life at UBC (Victoria: Heritage House, 2017). He has been the archivist for the UBC student society (the AMS) for more than twenty years and has also written a murder mystery and two academic books on the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. His murder mystery, Remember, Remember (Bristol: UKA Press) was nominated for an Arthur Ellis crime writing award in 2005. His latest book is Sherlockian Musings: Thoughts on the Sherlock Holmes Stories (London: MX Publishing, 2019). Originally from Montreal, he has a history degree from McGill University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba, and two degrees from the University of British Columbia: a PhD in English and a master’s degree in archival studies.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#749 Robin Blaser in retrospect”