#747 The mammoth in the room

Rise of the Necrofauna: The Science, Ethics and Risks of De-Extinction

by Britt Wray, with a foreword by George Church

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2019

$32.95 / 9781771644723

Review by Tom Koppel

*

Welcome to the brave new world of 21st century genetics and the quest by a few clusters of audacious scientists to bring back animal species that have been extinct for hundreds or even thousands of years.

Welcome to the brave new world of 21st century genetics and the quest by a few clusters of audacious scientists to bring back animal species that have been extinct for hundreds or even thousands of years.

Britt Wray, a Canadian science broadcaster, now based in Copenhagen, became “transfixed” by this topic around 2012 and has produced radio documentaries on it for the CBC and other outlets. She narrates in captivating prose the ongoing story of a movement whose experiments aim at nothing less than to reverse the extinction of certain iconic species, such as the woolly mammoth and the passenger pigeon.

Spoiler alert. None of these hoped-for critters have yet been created. Wray thinks some “facsimile” of a vanished species may walk (or fly) the Earth in the next decade or so, but she casts a sceptical eye on many of the claims made by leaders of the effort. To date, she believes, the movement has promised a lot more than it has delivered. “If taken without scrutiny,” she writes, “the term de-extinction as it is widely used suggests that reversing extinction might actually be achievable. That idea, however, is a sham. In no way can we ever undo the erasure of an entire way of life.”

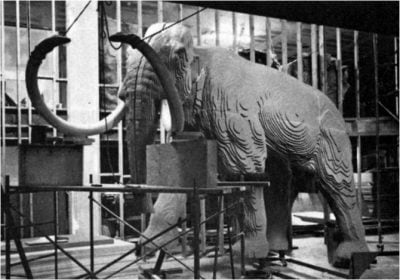

Take the woolly mammoth, for example. “A genetically and behaviourally exact copy of the original woolly mammoth would first need to appear,” she writes. This cannot be done by selectively breeding Asian elephants, the mammoth’s closest living relative, because mammoths are “too evolutionarily divergent” and did not “directly descend from them.” One could try to edit mammoth genes into a living elephant, but “there’d be a slew of elephant genes in the mix.” “Cloning can get close,” she asserts, “but it’s not possible when tissue was not taken from the animal sometime before it died and immediately frozen.”

Some of the scientists Wray has interviewed and profiled here would reject that assessment, including George Church of Harvard Medical School, who wrote a foreword to the book. Church argues that the “costs of reading and writing DNA in general, and ancient DNA, in particular have dropped about a millionfold…. These methods do not require frozen samples…. We already have synthetic genome projects … at the 4 million base pair scale — making plausible the 1.4 million changes between Asian elephant and mammoth (or some pragmatic subset of that number).”

If “base pair” and similar terminology do not exactly roll off your tongue, fear not. Wray valiantly provides a short course in genetics that clarifies most of the issues related to selective breeding, gene engineering, cloning, and the problems that arise when raising modified animals using surrogate mothers.

“It is unlikely,” she concludes, “in every imaginable case to recreate a completely genetically identical copy of an extinct species — identical in both its nuclear and its mitochondrial DNA. That will change only when we are able to synthesize full genomes from scratch with 100 percent accuracy and when the process becomes cheaper. But even then,” she adds, “there will be no womb from the extinct species for the un-extinct specimen to develop in, so differences are unavoidable.” Hence, the resulting facsimile would not be a carbon copy of a mammoth or passenger pigeon, and the surrogate mother (an Asian elephant, or a band-tailed pigeon) might not be able to teach it what it needs to know to duplicate the ancient fauna’s behaviour.

If she is right, why bother? De-extinction enthusiasts believe that these facsimile species (e.g. genetically modified Asian elephants or band-tailed pigeons) might be able to re-occupy (or even re-establish) the ecosystem niches once dominated by the extinct species, thereby providing necessary environmental “services” that are currently missing. A modified Asian elephant adapted to Arctic conditions, for example, could trample the tundra, graze heavily, greatly lower soil temperatures and reduce today’s worrisome melting of the permafrost. The hope is to re-create the conditions of what was the early post-Ice Age “mammoth steppe” in Siberia and parts of northern Canada.

In the case of passenger pigeons, which numbered in the billions, a US non-profit called Revive and Restore wants to use modified band-tailed pigeons to re-create some of the forest disturbance that passenger pigeons were alleged to have caused. Its website argues that:

Passenger pigeons and fire were the major sources of beneficial and continual forest disturbances for tens of thousands of years. Since the extinction of the passenger pigeon humans have suppressed fires, leaving no consistent source of forest disturbance. While the eastern United States has experienced vast reforestation over the past seventy-five years, regeneration has virtually stopped, leaving new and old forest stands stagnant and native species on the decline. By reviving the ecological role of passenger pigeons we can restore and perpetuate forest regeneration cycles naturally.

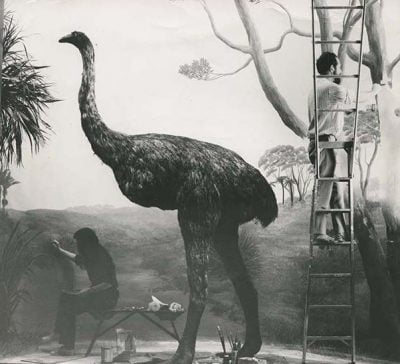

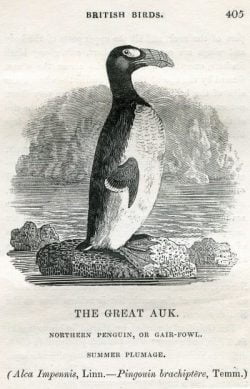

Other favourite candidates for de-extinction include the giant moa birds of New Zealand; Spain’s bucardo, a mountain goat; the European and Mediterranean aurochs, a wild cattle species; as well as the flightless great auk and the gastric-brooding frog.

In nearly everything related to de-extinction, there are major open questions and controversy abounds: have the relevant ecosystems changed so drastically since the extinction of a keystone species that there is no longer a niche to fill?

Where will the newly-minted, genetically-modified species go in the “wild?” To private lands or public ones?

Can they be patented? Most likely yes, at least in the US. If so, will there be a profit motive involved?

Is there a danger that they will become invasive and do unforeseen harm to otherwise healthy ecosystems? And then, who is responsible?

Ethical quandaries include assessing the pain and suffering entailed in experimenting on so many animals, even if the long-term goal is arguably a noble one. Wray’s account depicts numerous failures, with many animals dying in the process and others being exploited as surrogates. If the resulting facsimile species must be held in captivity before (if ever) being released into the “wild,” what is the moral cost of that? Finally, how greatly might new technologies or breakthroughs change the future picture? Wray does not duck any of these issues, and deals fairly with them while also showing respect for the scientists who are dedicated to this work.

Wray comes to her project by proclaiming a healthy personal scepticism and doing considerable personal soul-searching. She asks: “merely by putting a book … out there, am I aiding and abetting a movement that I do not wholeheartedly support?” She worries that de-extinction could divert scarce resources from other conservation projects, or lull people into being less vigilant regarding current threats of extinction. She quotes a conservation biologist who scoldingly says: “I think it is a real shame you are not writing about real solutions. Is de-extinction a solution? It’s a tiny, microscopic marginal solution with a lot of problems. There’s a lot of fantastic people out there doing incredible things to save biodiversity, save species, but this is not anywhere near the top of the list.”

In the end, however, Wray goes easy on the de-extinction scientists, calling them “visionaries.” She admits to being excited about the “fascinating technological feat” and is sufficiently impressed by the enthusiasm and sincerity of some of the movement’s leaders to give them the benefit of many doubts. “I am now a lot more trusting of their motives and admiring of their efforts,” she writes, especially since some of the technologies may also help to save currently endangered species that are not yet extinct. “I do believe,” she writes, “that de-extinction could create a real sense of hope about the future of conservation for a lot of people. And that matters enormously. But it doesn’t drown out the other questions I have about it.”

Through intimate personal interviews, Wray carefully and thoughtfully profiles the de-extinction leaders and allows them to argue the case on their own terms. Whichever side readers come down on, Rise of the Necrofauna will help greatly in following the almost inevitable continuation, or even acceleration, of these new and radical scientific developments.

*

Tom Koppel is a veteran B.C. author and journalist who has published five books on history and science. For 35 years, he has contributed feature articles to major magazines, including Canadian Geographic, Archaeology, American Archaeology, Equinox, The Beaver, Reader’s Digest, Western Living, Islands, Oceans, and The Progressive. His book Kanaka: The Untold Story of Hawaiian Pioneers in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (Whitecap Books, 1995) is available from koppel@saltspring.com. Tom lives with his wife Annie Palovcik on Salt Spring Island.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “#747 The mammoth in the room”

Comments are closed.