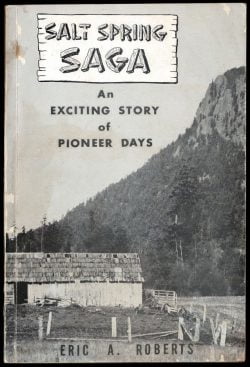

#745 The secret spy of Salt Spring

Agent Jack: The True Story of MI5’s Secret Nazi Hunter

by Robert Hutton

London: St. Martin’s Press, 2019. Distributed in Canada by Raincoast Books

Reviewed by Julian Wake

*

When I first read Eric Roberts’ Salt Spring Saga, someone here on Salt Spring — my home — told me that he had been an important British spy. Had loose lips flapped? Every agent was bound by a lifetime oath to say nothing about their careers. When Roberts came to the west coast, he had been “pushed out of” MI5 because, unsurprisingly, he was becoming paranoid, depressed, and unhealthy with a drinking problem. Salt Spring must, at last, have felt safe despite a relapse into fear and suspicion in 1968 when an MI5 agent visited to ask him about his half-articulated suspicions of double agents before his retirement. Were there others to unearth than the infamous Cambridge five?

When I first read Eric Roberts’ Salt Spring Saga, someone here on Salt Spring — my home — told me that he had been an important British spy. Had loose lips flapped? Every agent was bound by a lifetime oath to say nothing about their careers. When Roberts came to the west coast, he had been “pushed out of” MI5 because, unsurprisingly, he was becoming paranoid, depressed, and unhealthy with a drinking problem. Salt Spring must, at last, have felt safe despite a relapse into fear and suspicion in 1968 when an MI5 agent visited to ask him about his half-articulated suspicions of double agents before his retirement. Were there others to unearth than the infamous Cambridge five?

Roberts worked for MI5 from 1939 until 1956, when traitors were active. Some MI5 files from the war began to be released in about 2008. Key records about Roberts’ activities were not opened until October 2014. Robert Hutton, author of Agent Jack: The True Story of MI5’s Secret Nazi Hunter, has been scrupulous to stick to what the records actually reveal about Roberts’ career. He admits that much has been destroyed in the decades since Roberts worked. His account is based on 600 transcripts of conversations between Roberts and his treacherous contacts, a few family archives, and interviews with some surviving dramatis personae or their relatives.

Roberts worked for MI5 from 1939 until 1956, when traitors were active. Some MI5 files from the war began to be released in about 2008. Key records about Roberts’ activities were not opened until October 2014. Robert Hutton, author of Agent Jack: The True Story of MI5’s Secret Nazi Hunter, has been scrupulous to stick to what the records actually reveal about Roberts’ career. He admits that much has been destroyed in the decades since Roberts worked. His account is based on 600 transcripts of conversations between Roberts and his treacherous contacts, a few family archives, and interviews with some surviving dramatis personae or their relatives.

The release of formerly classified information has of course led to fictionalization. Kate Atkinson’s hero, Godfrey Toby, in Transcriptions (Penguin Random House, 2018) is built on Eric Roberts. Notwithstanding persistent revelations of extraordinary duplicity and ruthlessness, the world of spies is far too titillating to be left to straight histories. And yet Hutton does an admirable job in holding a reader’s attention, partly by an astute deployment of two very relevant issues: first, the tension between civil liberties and an arguable need during war for a secret police, and second, the perils of trust.

Surprisingly, Hutton does not dwell on the moral dilemmas of pretending to be what you are not; nor does he deal with the glamorization of a necessary but unsavoury occupation. At one point, Roberts belonged to the Communist Party, the National Front of British Fascists, other fringe right-wing groups that he continued to join until the outbreak of war, the private Industrial Intelligence Bureau, and the special constabulary of London. Permutations of deception (or deceit) continued to be a hallmark of his and his handlers’ trade. After the war, a key Austrian agent for Roberts, believing he was working for the Gestapo, proposed that he infiltrate the communist party, while in fact he was an unwitting MI5 informant: a triple agent!

How and why was Roberts recruited to this ambiguous profession? Vetting appears to have been minimal. He certainly wasn’t invited as a boarding school boy for Sunday lunch at a plummy suburban home where a coterie of prospects was subtly vetted by the carver of the roast under the warm smiles of the hostess. Or was it the cook, not the carver, who did the vetting? He didn’t undergo one of those fierce tests to see how a prospect might, for example, dispose of the cherry stones from the pudding, as John le Carré famously joked. (le Carré’s protagonist confounded his interlocutors by swallowing them. I cannot recall if he proved to be a good’un or a traitor.)

Roberts was unlikely spy material. His first association in London to which he went as a teenager from a potentially obscure life in Cornwall was with the British Fascisti (BF). This organization — unassociated with the British Union of Fascists (BUF) — was established by an admirer of Mussolini, who liked the way “Il Duce” ended chaos and communism in Italy. Hutton glosses over Roberts’ reasons for joining the BF, a fringe right-wing group known as the Bloody Fools. He suggests he was motivated by loneliness and boredom, which seems plausible.

The BUF, formed in 1932, attracted 40,000 followers from all walks of life, from working to upper classes. It changed its name to the British Union in 1937. The party was outlawed soon after the start of war and its leaders, including the dreadful Sir Oswald Mosley, were imprisoned. It seems remarkable now that so few of its members acted on their apparent beliefs. Politically disaffected, horrendously anti-Semitic, nostalgic for a well-ordered Britain that never existed except in ideals, with very few exceptions they knuckled down to war work once it was clear what was at stake. It is with some of those exceptions that Roberts ingratiated himself and did invaluable work.

It was from the BF that an oddball called Maxwell Knight recruited Roberts (and many others) to be a spy for a private agency called the Industrial Intelligence Bureau (IIB), whose customers were British capitalists worried about socialism and potential strikes. (How many “Think Tanks” and Foundations have similar secret agendas today?) Curiously, Knight’s first task was to infiltrate the BF, whose agenda did not contradict that of the IIB. The IIB knew that they would find promising recruits within its ranks. Roberts soon had a realistic knowledge of how many otherwise respectable British people had been seduced by National Socialism and duped by anti-Semitic propaganda.

Roberts was enthusiastic about becoming a spy. Like Knight, he had been charmed by the exciting portrait of Rudyard Kipling’s adventure novel Kim (1901), and here he was, still in his teens, living a fantasy. What a tonic to supplement a dull life as a bank employee. There was no school for spies. The trade was learned on the job, and tradecraft developed as ingenuity and need dictated. Knight gave him considerable personal attention as he did all his agents. He was an eccentric intelligence officer. Roberts began attending communist meetings with the long-term goal of being asked to join the party. He became a member but was constrained by Knight to surveillance work only, mainly tailing Ivor Montague, who became a somewhat ineffective Soviet spy in 1940. On the same day that the General Strike of 1926 ended, Roberts became a volunteer policeman, one of 60,000 special constables. Official interest in both communism and the British Fascisti waned. The services that Knight and Roberts had provided were no longer in demand.

In the 1930s, communism and fascism were again perceived in official quarters as a threat. Knight was recruited by MI6, and was switched to MI5 just as the British Blackshirts (BUF) showed themselves capable of using brutal violence in the summer of 1934. In the same year, their ideological cousins in Germany were revealing their true colours by arresting and executing their perceived opponents (“the night of the long knives”). Almost overnight, fascism had disgusted formerly complacent Conservative politicians, and Knight and Roberts were back in business. Knight’s target was the BUF, and Roberts, despite his limited success in infiltrating the communist party, was going to be his torpedo.

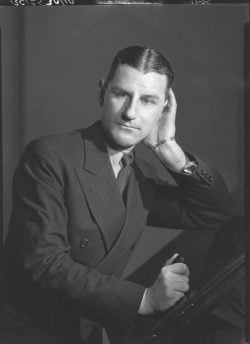

For five years, working under his own name, Roberts patiently ingratiated himself with what had become an organization with its own intelligence service that suspiciously monitored its own members. At the same time, he serendipitously discovered compromising information about a communist agent and joined at least fifteen other subversive groups. He evidently thrived on the work, enjoyed a happy family life and, at that time, staved off the strains of living a double life. Audrey, his wife, was aware of his second job and supported him. He completely fooled senior BUF members that he was a “loyal pro-German.” In May 1940, with the BUF outlawed, he was briefly without a second occupation until MI5 requested that his bank release him for special wartime duties. Knight and another admirer in the Security Service recommended him on the grounds that he was “familiar with everything connected with the pro-Nazi organizations in this country.”

Roberts was handpicked to work under Victor Rothschild, director of counter-sabotage, to penetrate a spy ring within the Siemens Corporation. Siemens, a German company, had collected intelligence quite legally before the war, which accounted in part for the lack of a German underground infrastructure in Britain. Under the code name Jack King, using a fake Gestapo I.D. card, Roberts set himself up as the Gestapo’s go-to man in Britain. Soon a handful of men and women reported directly to him, their soi-disant Gestapo intelligence officer, in an apartment near Paddington. Every conversation was recorded, none of which could have been used in a trial. Through them, and in addition, Roberts knew of or kept direct tabs on almost 500 other Nazi sympathisers and wannabe Fifth Columnists. It is not clear how he got away with his alias when many British fascists must have known him under his real name before the war. As Hutton illustrates, his quick wits and charm saved him from several perilous situations. Nor do we learn how Nazi sympathisers who must have been reported by fellow citizens were dealt with by the Special Branch of the police. Roberts himself was reported by a neighbour in Epsom.

First and second-generation Germans and Austrians were amongst this fifth column, believing that their secrets were being passed on to Berlin by Jack King. In 1938, Guy Liddell — director of counter espionage at the Home Office — had been able to alert his American counterparts to the operations of Nazi spies in the US. When arrested, one agent boasted of a German agent in every armament factory and shipyard in America. The FBI bungled the case, but its principal agent (who had been dismissed) wrote the book on which the movie Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939) was based. An Austrian, who became a naturalized British citizen in 1937, learned about and passed on to “Jack King” four critical top secrets: the development of the de Havilland fighter-bomber, the prototype anti-radar system known as “Window,” the location of the headquarters of the Special Operations Executive, and the existence of Bletchley Park. He never doubted that his purloined information went to Germany.

At the start of the war, there were 70,000 such potential “enemy aliens.” The chief protagonists about what to do with them were the senior civil servant at the Home Office, Sir Alexander Maxwell, and his colleague Guy Liddell. Both were decent men. Maxwell was passionate about what would today be called civil liberties, while Liddell was deeply exercised by the challenges of his job and having the means to get it done. He feared that many more fellow citizens were ready to aid Germany after an invasion than the establishment could imagine, and that “liberal kid gloves” were not the way to manage them. The one would not countenance internment as in the First World War, the other was aware of how prudence dictated an overdose of caution. Even after the fear of invasion eased in 1941, the tension between potential abuse of emergency powers and the rules preventing totalitarian actions continued. Some MI5 staff vehemently opposed the Fifth Column Operation and the possibility of using secret evidence to imprison people without a trial. As the operation became very successful, the tables turned. In another case, Liddell’s principal assistant was pragmatic: “It should be considered whether it is worthwhile losing a useful source of intelligence regarding subversive people in this country for the doubtful success of prosecuting … for an offence for which she may merely receive a caution or a small fine.” It was in MI5’s interest to protect their sources from police prosecution and imprisonment.

Maxwell and defence barristers stayed vigilant even as they may have acknowledged many complicating factors. How could internment of Jews who had fled Germany be countenanced? How could screening be done given an extreme shortage of manpower? Where could they be interned? Had Norway been undermined by a Fifth Column or not? In the event, internment won. Under the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act, in an atmosphere of terror at invasion, 753 BUF members, 22,000 Germans and Austrians, and 4,000 Italians were interned. Individuals suffered dreadful injustices, some of whom must have felt they had escaped the fire to fall into the cauldron. Many were shipped to Canada. One ship with 1,200 internees was torpedoed, with all lives lost.

How dangerous was King’s odd cast of misfits and idiots to Britain? Hutton is persuasive that they could have caused serious damage if Germany had bothered to find a way to learn what they knew and to use that intelligence, inter alia, for bombing raids and organized sabotage. Roberts’ work was vital when invasion was a threat. He learned who might provide help to an Axis landing force. Hutton vividly traces how critical information obtained by crypto-Nazis in Britain went to Roberts and MI5, instead of being transmitted to the Gestapo via neutral embassies in London.

How much danger did they pose to Roberts had they rumbled him? Most of his subjects seem ludicrous now. It is hard to judge another person’s delusions and assess what damage they might cause. MI5 recognized this, which may account for how this operation maintained a low profile. Only one of his fascist dupes (should they be called clients?) appears to have had cold-blooded intelligence and a capacity for ruthlessness. Yet even she ignored some transparent clues about how improbably Roberts acted as a German agent. She questioned why information she gave him never led to bombing raids, but continued to trust him as the Gestapo’s man in Britain. She was the daughter of the popular Australian composer, May Brahe, wife of an interned BUF member, vehemently anti-British and anti-Semitic. She was a magnet for disaffected Brits who would act to promote a German victory, and she saved Agent Jack the trouble of identifying them.

Every one of these people, who could have been charged with treachery, would have faced the death penalty had they been brought to trial. Luckily for them, it was in Britain’s interest, even after the war, to keep tabs on them rather than expose them (and therefore Roberts) in public trials. MI5 could and did use them, preferring to know about their activities than to send them underground. MI5 had, Hutton writes,

… no formal powers of action at all. The British state had reconciled itself to the need for something as un-British as a secret police by having one, but not acknowledging it. The Security Service (MI5) could investigate, but once it had identified a suspect, it was supposed to work with the police – usually the Special Branch detectives who dealt with sensitive cases – and the Director of Public Prosecutions, to put them on trial like any other criminal.

Prosecutors were vigilant about entrapment or provocation that would have a case thrown out. Instead of having their agents testify publicly in order to prosecute, MI5 decided that awareness and monitoring of suspects were a lesser risk than exposure of an agent. In this way, MI5 effectively controlled active Nazi sympathisers.

Under the Treachery Act of May 1940, which was intended to be temporary, sixteen people were shot by firing squad or hanged for treachery. Only five British subjects were executed, none of them working in Roberts’ stable. One was the son of German immigrants, one was an engineer, two were servicemen, and the fifth was a resident of Gibraltar. The other eleven were German agents, some of whom had arrived with lamentable training by parachute. The Act was suspended in February 1946.

As the war wound down, normal monitoring of subversive groups by the Special Branch could resume. This surveillance would be applied to most of the 500 or so fascists that Roberts reported on. The “conscious agents,” those who thought they were acting for the Nazis through Jack King, would be considered traitors, had they been prosecuted. Prosecutions would be difficult on practical grounds because they would reveal the operation and its dodgy tactics to the Home Office. The irony that the last two Nazi medals awarded in the war were minted in a Jewish bank and awarded by the British Security Service to two people the Gestapo had never heard of, would not have mitigated official censorship. The recipients of the medals died believing they had done their bit for Nazi Germany, each no doubt treasuring the fake Kriegswerdienstkreuz medal given them by Agent Jack.

The key to Eric Roberts’ success was his way of making people trust him, which is of course quite different from, but not necessarily contradictory to, trustworthiness. This quality was imperceptible to his employees at the Westminster Bank where he had served as a clerk for fifteen years. He had charm. To his employer, he had integrity. Hutton is strong on the detail of his early infiltration, his wits to forestall suspicion, and his ability to maintain the trust of frightened yet fanatical haters.

Agent Jack also contains good profiles of some interesting characters, like the brilliant Victor Rothschild, head of MI5’s counter-sabotage section where Roberts was seconded in the war, and the ubiquitous Maxwell Knight. Some say that the latter’s character and activities were the basis of Ian Fleming’s James Bond. Fleming would certainly have known Knight. On the whole, this book avoids passages aimed at Hollywood and is the stronger for that.

Was Roberts amused by all the spy fiction that developed towards the end of his life or was he exasperated by how inadequately most of it depicts the mind-bending tension? He tried his hand at the genre in a series of short stories set in Vienna. Unfortunately, the nature of Roberts’ career precluded formal acknowledgement of his contributions to the war. Rothschild recommended a year’s salary and an MBE. They did not come to pass, some say because MI5 was embarrassed by the methods they had used in containing the fifth column. Roberts said he did not seek recognition.

Nobody except his family apparently knew of his extraordinary career when he died peacefully in Ganges in 1972. Robert Hutton has done splendidly to give Eric Roberts his due, albeit posthumously. It is reassuring to know that his choice of refuge on the west coast was a good one where he and his family were safe to overcome the stresses of his double life and cultivate their island garden.

*

Born in the UK of Welsh, English, and Scottish ancestry, Julian Wake came to Vancouver in 1966 to study forestry at UBC. He switched fields and earned BA and MA degrees in social anthropology. He has lived a countercultural life in the Kootenays and worked in multiple capacities for many First Nations in several areas of British Columbia, and in developing countries including Nepal, Jamaica, and Peru. Julian lives in Ganges on Salt Spring Island.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#745 The secret spy of Salt Spring”

I just finished the book. Terrific storytelling. Times of crisis always find a way of providing their secrets, often years and even decades after the fact. The secrets of ‘Agent Jack’ revealed so close to home make for a fascinating addition to our regional history.