#733 Pompeii of the Northwest Coast

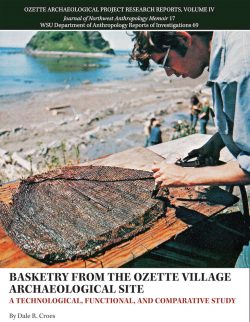

Basketry from the Ozette Village Archaeological Site: A Technological, Functional, and Comparative Study. Ozette Archaeological Research Reports Volume IV. Washington State University Department of Anthropology, Reports of Investigations Number 69

by Dale R. Croes (author), Alexandra L.C. Martin (design), and Darby C. Stapp (editor)

Richland, WA: Journal of Northwest Anthropology (JONA), Memoir Number 17, August 2019

$34.99 (U.S.) / 9781095915691

Reviewed by Andrea Laforet

Available at NorthwestAnthropology.com and on Amazon.com

*

The purpose of this book is twofold: the publication of archaeologist Dale Croes’ 1977 Ph.D. dissertation on the basketry recovered from Ozette village and the placement of the results of that work in the context of analysis of basketry recovered from wet sites on the ethnographic Northwest Coast in the years between 1977 and the present day. Within the volume, the text of Croes’ doctoral thesis is presented in its original form, apart from a few illustrations that are clearly indicated as supplementing original figures. Footnotes present information generated since 1977 as well as commentary on the relationship of the new information to the thesis data. An index has been added. The thesis bibliography has been updated, with asterisks designating works referenced in the footnotes.

The purpose of this book is twofold: the publication of archaeologist Dale Croes’ 1977 Ph.D. dissertation on the basketry recovered from Ozette village and the placement of the results of that work in the context of analysis of basketry recovered from wet sites on the ethnographic Northwest Coast in the years between 1977 and the present day. Within the volume, the text of Croes’ doctoral thesis is presented in its original form, apart from a few illustrations that are clearly indicated as supplementing original figures. Footnotes present information generated since 1977 as well as commentary on the relationship of the new information to the thesis data. An index has been added. The thesis bibliography has been updated, with asterisks designating works referenced in the footnotes.

The principal focus of the book is the basketry recovered from the site at Ozette, the southernmost historic village of the Makah of the Olympic Peninsula, partly buried in a mudslide between three hundred and five hundred years ago. During the winter of 1969-70, a storm washed away part of the mud, revealing wooden artifacts that had been covered since the slide. Croes’ basketry study is a component of the subsequent archaeological investigation undertaken by Washington State University in partnership with the Makah.

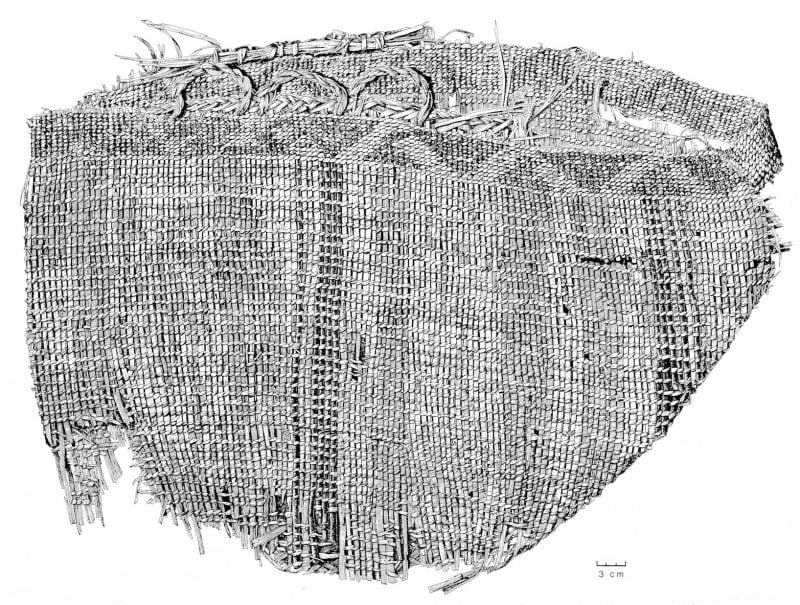

The vegetal material preserved by the mud included baskets and other items of basketry made with basketry techniques, such as mats, tumplines, cradles, and hats. Croes analysed the technical attributes of the 446 basketry items recovered. Technical attributes included, but were not limited to, materials, shape, construction techniques, and decorative techniques. Croes noted that he had been well prepared to recognize the salient features of basketry construction by mandatory instruction in basket-making provided by Makah basket makers before he began his analysis. Initially sceptical of the value of this instruction, he had come to appreciate that it, and the knowledge that lay behind it, had been pivotal to his understanding of the characteristics of the basketry in the site.

On the basis of clusters of attributes, Croes developed typological sets, and subsequently developed functional sets, i.e. basket types used for particular purposes, such as fishing tackle bags, storage baskets, whaling harpoon bags, and burden baskets, drawing on ethnographic information relating to Makah and Nuuchahnulth basketry from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He went on to develop comparisons between Ozette basketry and the basketry recovered from other wet sites in Washington State and British Columbia. In the 1970s these included the Lachane site in northern British Columbia, Axeti on the north central coast, Little Qualicum River on Vancouver Island, Musqueam Northeast at Vancouver, and, in Washington State, English Camp, Fishtown, Conway, Biderbost, Hoko River, and the Wapato Creek Fish Weir site.

The overall shape of the book is governed by the methodology of the thesis, which addresses in turn the classification of attributes, the classification of basket types, and the generation and analysis of functional sets, with a similar analytical approach for hats, mats and other objects constructed with basketry materials and techniques. The approach is rigorous and exhaustive, with each section accompanied by diagrams, tables and, as required, charts based on statistical analysis.

The footnotes constitute a second stream of discussion, intended to amplify the original text and to be read along with it. Each footnote is tied to a point made in the original text, updating information relating to wet sites discussed in the thesis, offering information about additional wet sites throughout the Northwest Coast excavated since 1977, such as Qwu?gwes in southern Puget Sound and Ditidaht sites on southwestern Vancouver Island. In a few cases footnotes offer new data relating to specific aspects of the work at Ozette. Some of the footnotes are quite short; others are extensive, offering both technical and analytical summaries, and sometimes including illustrations and charts presenting statistical analysis of certain data.

In some instances, e.g. footnotes relating to the slat coil basket recovered from the Fraser Valley site, Liyomxetel, and the Long Ago Person Found hat, recovered in 1999 from Tatshenshini-Alsek Park in northern British Columbia, interesting details are revealed in a succession of footnotes developed to follow separate points in the exposition and thus located in different sections of the book. This can be mildly frustrating. On the positive side it can encourage the reader to locate and read the original article referenced in the footnotes.

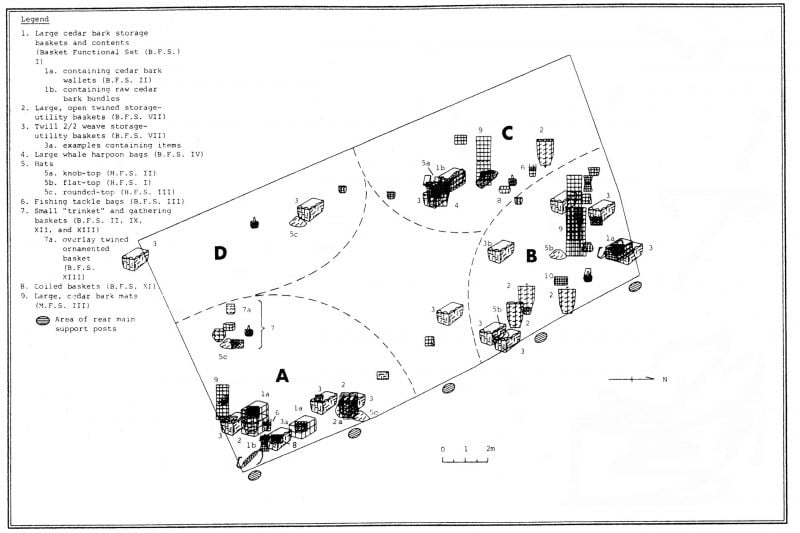

Emerging from the methodical and highly detailed analysis of the basketry found at Ozette are insights into household life in this village at the moment time stopped. A basket of twelve smooth boiling stones was found in a hearth area, apparently waiting for a fire that was never lit. The contents of other baskets speak to the diversity and specificity of the household’s resources. A list of the sea gull bones found in various baskets occupies a full page (p. 213). A particularly compelling illustration, Map 24, p. 382, shows the distribution of basketry items in House 1, with many items clustered in the corners that ethnographic information suggests were family living areas. The patterns in which basketry items such as flat-topped hats and knobbed hats, and basketry related to whaling, were distributed through the living areas of the house indicate the relative wealth of the families living there. In research conducted since the completion of the thesis, Croes analysed the volume of storage baskets in one Ozette functional set to calculate the volume of food that could be stored in a house and the number of meals it could provide to an estimated thirty members of a household (p. 248, fn 203).

Reading the Book

Ozette Archaeological Research Reports Volume IV. Basketry from the Ozette Village Archaeological Site: A Technical, Functional and Comparative Study is highly technical. Although it can be read and understood without prior knowledge of either archaeology or basketry, both certainly help. Croes provides his step-by-step explication of his analysis in prose that is relatively free of jargon. Nonetheless, the very nature of the topic requires that the reader have a high tolerance for technical information and the mastery of related terms.

Reproducing the dissertation virtually in its 1977 form made the preservation of one or two outdated features inevitable. Map 1, showing the distribution of waterlogged sites on the coast in 1977, preserves Northwest Coast tribal names, e.g. “Bella Bella,” and “Bella Coola,” which were in standard use by non-First Nations scholars in the 1970s, but have since been superseded. In two other instances, Croes has made adjustments. He retains the outdated term, “prehistory,” in the first place where it occurs, but substitutes the term, “ancient history,” thereafter. In an adjustment that brought a smile to my face, Croes notes that when an earlier scholar used the pronoun, “he,” to refer to basket makers, “he meant both genders” (p. 15, fn 12).

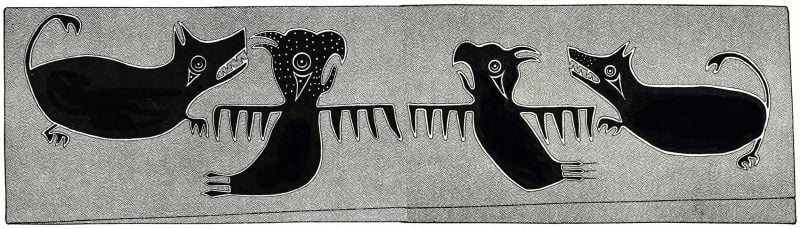

In his thesis Croes acknowledged the excellence of the original diagrams by Chris Walsh of basketry techniques and elements of construction. These occur throughout the original text and are very clear in respect to both technique and texture. Since many of these techniques are found in basketry outside Ozette, the diagrams can also be helpful in understanding basketry from historically related areas.

Conclusion

In this book Croes refers to Re-awakening Ancient Salish Sea Basketry Fifty Years of Basketry Studies in Culture and Science, which he published with Ed Carriere in 2018 (reviewed by Andrea Laforet in The Ormsby Review 462, January 17, 2019 — Ed). Although published a year earlier, in many ways Re-awakening Ancient Salish Sea Basketry Fifty Years of Basketry Studies in Culture and Science stands as a sequel to Ozette Archaeological Research Reports Volume IV. The two books share certain themes, e.g. Croes’ affirmation of the degree to which basketry from wet sites attests to technological continuity in certain Northwest Coast regions, the concept of intergenerational archaeology, and the value of the knowledge of contemporary basket makers for the interpretation and understanding of basketry from generations past.

The publication of a work of scholarship after a lapse of several decades always carries the risk of highlighting the work as out of its time. This has not happened here. This volume, unusual as its organization may be, confirms Croes’ 1977 dissertation as a foundational work in this area of research and expands it into a reference volume for currently known results of wet site basketry analysis on the Northwest Coast.

*

A specialist in the ethnography and material culture of British Columbia First Nations, Andrea Laforet (Ph.D. UBC 1974) retired as Director of Ethnology and Cultural Studies at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, Ottawa, in 2009. She continues to work independently with First Nations on current issues relating to ethnography and history.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

11 comments on “#733 Pompeii of the Northwest Coast”

This is a compelling article. How much heat could 12 boiling stones transmit? It feels like an investigation along the lines of the Burgess Shales. Remains of soft-bodied animals survived from 500 million years ago — and at Ozette household items made of perishable grasses also survived! Thanks for this review.

Mary Leah de Zwart: Thanks for your interest. To your question: a lot! White hot rocks in a fire were brushed of soot and dropped into watertight bentwood cedar boxes, found at the site, filled with water. They picked up the hot rocks with wooden tongs, the first two rocks to get the water hot and last one to get it boiling. Then they could cook, say, hard dried salmon and soften it like fresh. They had no ceramic or metal pots, so they put the heat into the vessel, not under it. Many bentwood boxes show signs of burnt marks where they were not stirred fast enough.

What was the use/significance of a basket full of seagull wings or seagull bones? PS fascinating article on the baskets.

Thanks for the great question, Steve; I wondered about that myself. This is from a Facebook reader, Trish Statham, in reply to the same question on a Facebook thread: http://traditionalanimalfoods.org/birds/shorebirds/page.aspx?id=6466&fbclid=IwAR2o871qBA6f3ZwA7yZ2sn6YksUx4e6z6YYl2L3x37glVG4frodFFGrDFOQ

Thanks for your question, Steve Housser. We found 35 piles of aligned cedar bark, 2-strand strings at the site. From museum collections, it looks like these strings were once wrapped with bird skins with the down still on them, creating down boas. These were twined together with sinew threads. I have pictures of these down blankets in the book. Since feathers/down, skin, sinew, hide and hair do not preserve in wet sites, only aligned cedar strings remain. So, for one, these basketry bags probably once held bird wings with feathers, bird skins with down, and sinew threads. So we are still left guessing even with good preservation of plant materials and animal bones. Thanks

Fond memories of those days. Wonderful to see your work and will order a copy for my Ozette/Makah collection. Andy Grosso

Andy, thanks! Your Dad was our great conservator and lab manager. Best, Dale

Thanks, Dale. Great to work with you again after 40 years — 1980-2020! I remember my trip to Ozette in 1980 very well. The photos, drawings, and maps you sent are a marvellous reminder. Best for now, Richard

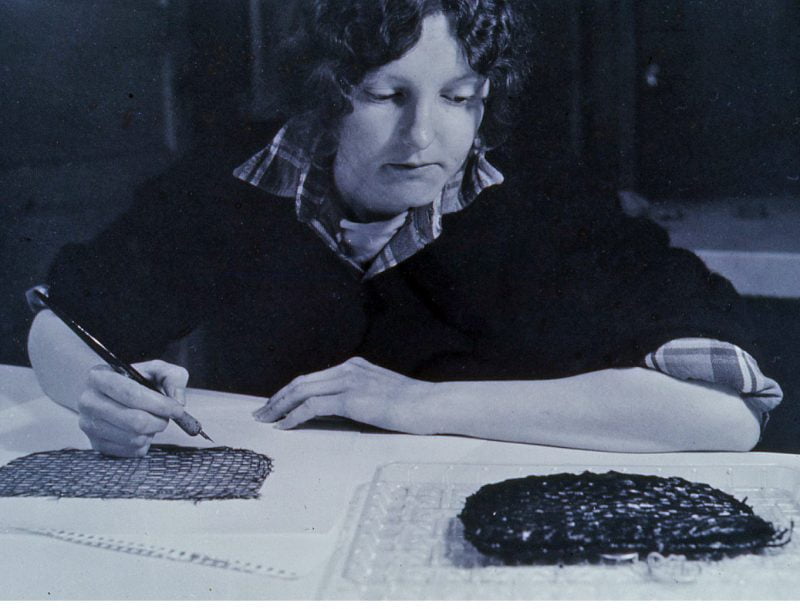

Great final photo. Thanks to you and Andrea. Best, Dale

Comments are closed.