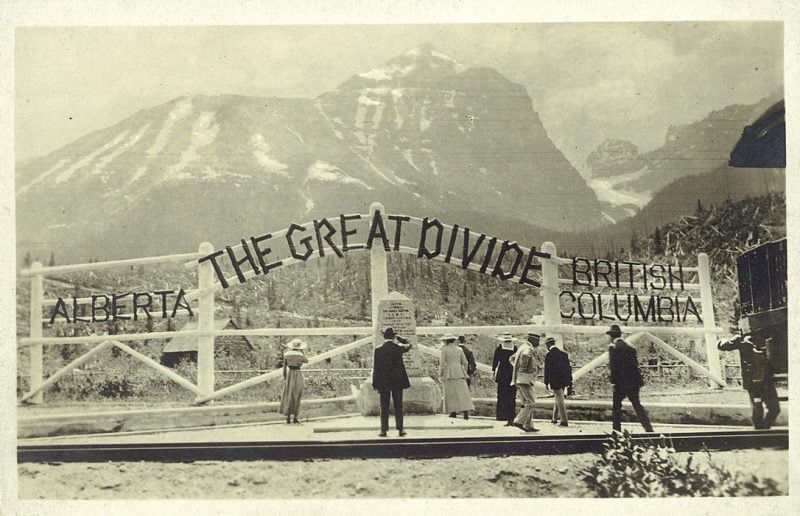

#730 Marking the Great Divide

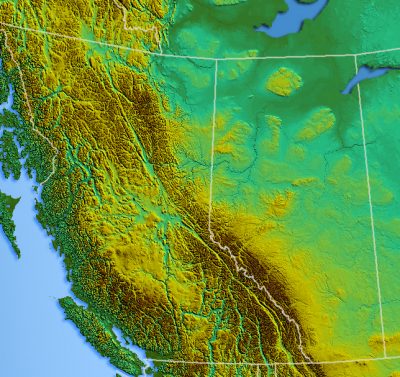

Surveying the 120th Meridian and the Great Divide: The Alberta-BC Boundary Survey, 1918-1924

by Jay Sherwood

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2019

$29.95 / 9781773860091

Reviewed by Keith Regular

*

Editor’s note: see also Robert Allen’s review of this book’s predecessor, Surveying the Great Divide: The Alberta/BC Boundary Survey, 1913-1917 (Caitlin Press, 2017) in The Ormsby Review no. 253, October 3, 2018.

*

Borders define us. Canada’s political and physical borders, such as mountain ramparts, isolate and cultivate distinct attitudes on environmental issues and economic agendas, and harden perspectives such as exist today between BC’s environmentalist focus and Alberta’s energy-driven economic program. The huge geographic and disparate landmass that is modern Canada attaches an enduring bordering effect to its citizens and, as evidenced by the recent genesis of WEXIT, has created as much mutual suspicion as collective celebration. The contemporary fractious relations that exist between Alberta and British Columbia, however, betray an earlier and much more amicable relationship when, like today, much was at stake.

Borders define us. Canada’s political and physical borders, such as mountain ramparts, isolate and cultivate distinct attitudes on environmental issues and economic agendas, and harden perspectives such as exist today between BC’s environmentalist focus and Alberta’s energy-driven economic program. The huge geographic and disparate landmass that is modern Canada attaches an enduring bordering effect to its citizens and, as evidenced by the recent genesis of WEXIT, has created as much mutual suspicion as collective celebration. The contemporary fractious relations that exist between Alberta and British Columbia, however, betray an earlier and much more amicable relationship when, like today, much was at stake.

Jay Sherwood’s Surveying the 120th Meridian and the Great Divide: The Alberta-BC Boundary Survey, 1918-1924, his second instalment on the history of the border survey is, like its predecessor, a timely offering. Defining the Alberta-British Columbia border was, in part, necessary to avoid jurisdictional disputes over latent economic potential offered by minerals, timber, and tourism. On a more practical level some inhabitants in the shared Peace River region did not know whether their land was located in Alberta or BC. Sherwood’s book is narrative driven and focuses on that portion of the border surveyed between 1918 and 1924. The book is rounded out by an added chapter on the completion of the boundary north of roughly fifty-seven degrees between 1950 and 1953, a remote area that was initially neglected but now required a survey because of petroleum exploration.

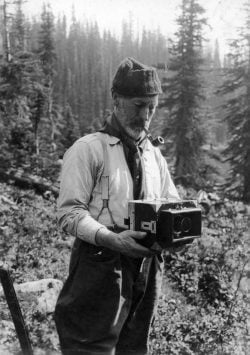

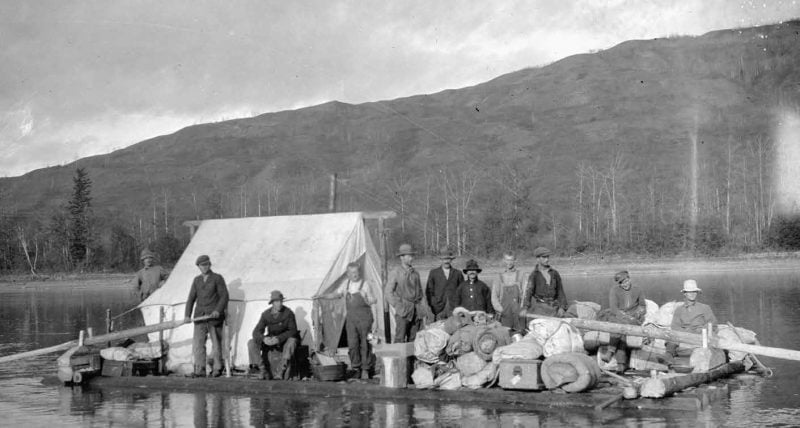

Surveying the 120th Meridian and the Great Divide is centred on the professionals, Edouard-Gaston Deville, Surveyor General of Canada, Richard W. Cautley, Alberta Commissioner and Dominion Commissioner, Arthur O. Wheeler, British Columbia Commissioner, and Alan J. Campbell, Assistant Surveyor, BC Crew. Sherwood introduces them with a mini biography that briefly but necessarily establishes the personal context for their involvement in the survey project. He also discusses the labour crews, properly so because their contribution was as imperative to success as that of the professionals. The many photographs that augment the text ensure that the prestigious and the ordinary do not remain faceless.

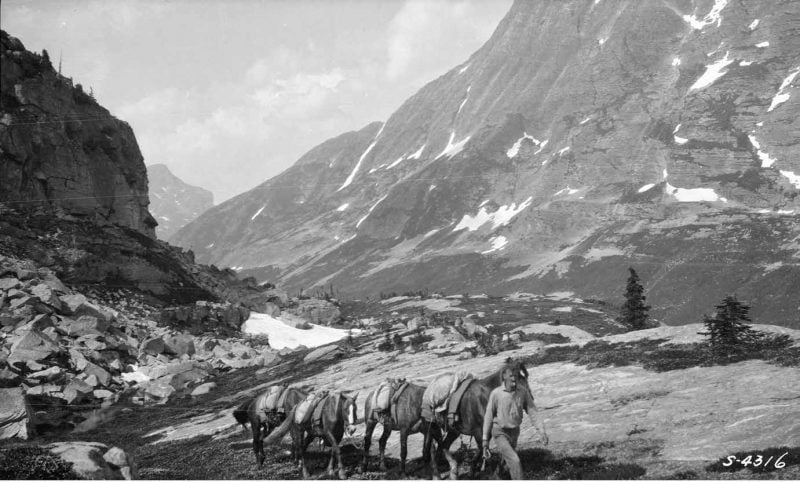

The text consists mostly of technical descriptions of day-to-day activities supported by extended quotes drawn mostly from logs and diaries as well as government documents and reports. These recount ongoing challenges as the crews wandered over the countryside, climbed mountains, clambered across shale, struggled with deadfall and muskeg, and braved narrow paths along cliff and scarp. Snow, rain, fog, flood, fire, and smoke tested patience and created doubt regarding the efficacy of what the men were seeking to accomplish. The logistics of supply proved a great challenge for men and horses especially when temperatures dipped to -40 degrees Celsius.

Sherwood presents the professionals as individuals of skill and significance. Deville, for example, introduced photogrammetry (photo-topographic surveying) to western Canada, which permitted a more exacting survey of the border. Sherwood recounts how it was necessary to return to the Philips Pass area of the Crowsnest to rectify an earlier survey error. Photographs taken during the survey were labelled and then used to produce the maps delineating the border between the two provinces. Human error, however, did admit to mistakes despite professional ability and the employment of the latest technology. The photographs enliven the text and validate the existence of a valuable cultural archive at Library and Archives Canada.

The leaders and crewmen were men of their times. Wheeler, for example, revealed his personal penchant for assigning names, to mountains in particular, betraying a colonialist mentality of superiority that involved a blithe dismissal of cultures in situ and long-standing Indigenous names. This occasioned a mini-jurisdictional dispute between Ottawa and BC, and more seriously reflected a lack of concern for the traditions of local Indigenous cultures. On the other hand, Wheeler’s commercial interests and astute observations on the necessity to preserve nature led to the establishment of BC’s Mount Assiniboine Provincial Park, a valuable inheritance for the citizens of today’s British Columbia and Canada.

Professional surveyors aside, this work also celebrates the endurance of the labouring men without whom this essential component in the nation-building enterprise would not have been possible. Like the draft animals, crewmen were veritable workhorses engaged in day-to-day struggles to deliver the tools and prodigious amounts of materials necessary to survey the line and build the physical monuments to mark the evidence of a job well done. For example, in his 1922 season, Cautley required no less than 9,980 kilograms of cement and 18,144 kilograms of gravel to mix with the cement to construct border monuments. Crewmen’s lives involved daily fatigue alongside scrapes, falls, skin irritations, cuts, and serious illnesses, such as ptomaine poisoning, with potentially dire consequences. Some men fell sick from Spanish Influenza and a cook was kicked in the face by a horse. The luck that protected the men from very serious outcomes did not accompany the animals, some of which died horrible and sometimes painfully slow deaths from falls.

As a specialized work of history, the book has much to recommend it, not least because it is a feast for the eyes. Sherwood has masterfully selected photographs, some his own, to illustrate his narrative. As well as illustrating the novel method of surveying, photogrammetry, the photos reveal Canada’s striking beauty, past and present, and provide a treasure trove for the modern environmentalist or climatologist wishing to discern how more recent climate woes may affect fauna and glacial ice. Much could be learned by a more intense study of the photos in this text and the archival collection from which these were taken. The two photographs on pages 126 and 140, for example, provide much on which to ruminate. One can only be awed by the men depicted in the photo on page 12. The dress of the man standing against an apparent winter backdrop suggests hard times, while the broad smile of another seemingly reflects not only great physical endurance but satisfaction with life and complete engagement with the current enterprise.

If Surveying the 120th Meridian and the Great Divide has a flaw it is the exhausting and taxing detail, much of it technical. One wishes that Sherwood had chosen to use his expertise to precis his offerings to draw the uninitiated reader further into events and processes. He also provides an over-abundance of minutiae to describe more or less repetitive actions in different locations. The narrative sometimes drags and, in places, will test all but the dedicated reader. Apart from its exceptional visual offerings, this is a book to be digested over time rather than enjoyed in one or two sittings. Nonetheless, Sherwood provides an essential account of the establishment of the Alberta-British Columbia border. The evolution of this line, the biographical glimpses of the significant personnel, and the revelatory wonderment of the photographs make for a work of significance, the more so because its rugged subject is not front and centre of the Canadian historical enterprise.

Surveying the 120th Meridian and the Great Divide deserves space on the library shelves of today’s diverse high schools and colleges – and there is precious little else on the subject. Much within its covers will encourage aspiring photographers, outdoor enthusiasts and naturalists, climatologists and environmentalists, and budding surveyors or engineers. Any student who holds the view that a career in surveying is a sentence to a mundane existence in a crowded urban space, or hammering surveying pegs to delineate town lots, will find inspiration in the important careers of Deville, Cautley, Wheeler, and Campbell.

Moreover, Sherwood reveals that a boundary was not just a matter of drawing a line. Rather, it involved overcoming great physical difficulties, marshalling great psychological strength, and summoning ingenuity at every turn. We owe the men central to this work, both the professionals and the labourers — and yes, even the beasts of burden — a great debt.

Surveying the 120th Meridian and the Great Divide can be measured on two levels: the broad driving narrative of the border survey combined with the complex and necessary contextual background of a professional practice that integrated photography and later aircraft; and stories of individual professional competence, the contours of the lives and work of labouring crewmen, and background themes of wilderness guiding, tourism, and mountain climbing. Sherwood even includes a labour dispute where the crewmen demanded wages for loss of time beyond their control. This mammoth survey project was initiated in the last year of the Great War, which sometimes seriously limited access to a labour pool, financial resources, and materials.

The book is much more than it appears at first glance. The story of drawing a border, it also constitutes an inventory of place names for mountainous and northern Alberta and British Columbia. Equally as significant, perhaps, is its timely lesson in what can be accomplished when federal and neighbouring provincial jurisdictions cooperate. Unintentionally, Surveying the 120th Meridian and the Great Divide contextualizes current intra-provincial and national relationships driven by environmentalism, struggling economies, national interests, and the aggravations, including WEXIT, resulting from the largely indecisive 2019 federal election.

*

Keith Regular is a retired high school teacher and principal who lives with his wife Anne in Cranbrook. He began teaching in Newfoundland before moving to Elkford Secondary School, in Elkford, B.C., in 1986, and retired from there in 2014. Keith holds a Ph.D. from Memorial University of Newfoundland and is a specialist in southern Alberta Native and newcomer economic interaction at the turn of the twentieth century. His book Neighbours and Networks: The Blood Tribe in the Southern Alberta Economy, 1884-1939, was published by the University of Calgary Press in 2009. Keith has completed a manuscript on the murder of Alberta Provincial Police constable Stephen Lawson in Coleman, Alberta, in 1922, and the subsequent hanging of his Italian immigrant killers after a trial that garnered national and international attention. He has a manuscript in progress on the famed train robbery at Sentinel, Alberta, and subsequent shootout and killing of two police officers, at the Bellevue Café, Bellevue, Alberta, in August 1920. Keith enjoys researching Aboriginal history and the history of the Crowsnest Pass and Elk Valley.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster