#729 When an inlet is an island

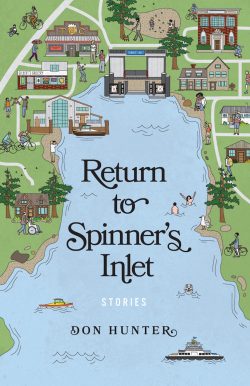

Return to Spinners Inlet

by Don Hunter

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2019

$22.00 / 9781771513081

Reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy

*

Although this collection of linked short stories is set in 2019, it evoked nostalgia in this reader. I was not surprised that its prequel, Spinner’s Inlet, was published in 1989 — which at once seems like just yesterday and eons ago; there is something of that era in the atmosphere of Return to Spinner’s Inlet. Or perhaps the identity of a small Gulf Island community is still cemented by institutions like the town newspaper, high school, and clinic, in which case I am tempted to set sails for the coast.

Although this collection of linked short stories is set in 2019, it evoked nostalgia in this reader. I was not surprised that its prequel, Spinner’s Inlet, was published in 1989 — which at once seems like just yesterday and eons ago; there is something of that era in the atmosphere of Return to Spinner’s Inlet. Or perhaps the identity of a small Gulf Island community is still cemented by institutions like the town newspaper, high school, and clinic, in which case I am tempted to set sails for the coast.

That Spinner’s Inlet was a nominee for the Leacock Medal for Humour is also not surprising. Canadian literature buffs would be hard pressed not to notice similarities between Return to Spinner’s Inlet and Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town. Hunter’s latest, like Stephen Leacock’s classic, lays bare (albeit more lightly) the foibles of a micro-culture where post office officials are the origin of town gossip, bars flout “last call” laws, and school teachers and religious leaders try in vain to enforce rules of grammar and godliness, respectively. The malingerers, hypochondriacs, lawsuit-happy barristers, anything-for-a story newspaper editors, and opportunistic politicians that populate the pages of Return to Spinner’s Inlet are archetypes of comedy.

This is not to say that Return to Spinner’s Inlet doesn’t reflect 21st century life in Canada. Sponsored refugees and exchange students represent a more diverse Canada, and the fact that the positions of mayor, reverend, and town constable are occupied by women is a further marker of contemporary society. The electronic revolution has also made its mark on Spinner’s Inlet: a pair of sibling geeks figures prominently in this story cycle, and email messages and social media platforms — facilitated largely by the younger generation — complement the communications provided by The Tidal Times.

In true comic style, the collection begins with a funeral (ABBA-themed, in which a queue for pallbearer positions necessitates a draw from a hat) and concludes with a wedding announcement (precipitated by a second funeral). Comic highlights include “Find the Artist,” in which an anonymous, Banksy-like street-art guerrilla erects portraits of the town’s big fish, inspiring the newspaper editor to sponsor a contest to identify said artist that puts all of the townspeople under suspicion; and “Pets and Plants,” in which an experiment to combine the previously distinct pet and horticultural festivals results in a marijuana plant, a lion, an iguana, and a PETA activist being in too close quarters.

Lest you think all is droll in Spinner’s Inlet, Hunter intersperses purely comic stories with more serious pieces. Among the best is “The New Doctor,” in which a young, diminutive female from way over on the Mainland overcomes the townspeople’s initial apprehension by displaying bravery and prowess in a medical emergency. In the most serious and moving piece in the collection, “Ali’s Story,” the titular character relates a story that is both harrowing and heart-warming (and subsequently makes the newspaper) about his relationship to Harry: in Kabul, Harry, as Ali Hanif’s protector, was responsible for the death of a young girl – a fighter for the Taliban. Harry’s ensuing PTSD resulted in the loss of his family, home, and career. When Ali discovered that Harry eventually ended up on the streets of Vancouver (through a re-location program) Ali rescued him and gave him a home on Spinner’s Inlet with the rest of the Hanif family.

Balancing tone is all important in what is largely comic writing, and Hunter delicately oscillates the observations of his mostly detached third-person narrative between the favourable and the disparaging. Pettiness, insularity, and smugness exist alongside magnanimity, altruism, and cooperation.

Hunter’s inlet is, for all literary intents and purposes, an island — separate and isolated — and thus, invites a brief reflection on island literature. After all, islands have been the stuff of mythology — Avalon and Atlantis, for example — and figure prominently in works as varied as Thomas More’s Utopia, William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Daniel Dafoe’s Robinson Crusoe, William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, and Jack Hodgins’ The Invention of the World. Whether their approach is utopic, dystopic, or somewhere in between, writers are attracted to islands for their utility as microcosms of the “real world;” at the same time, however, islands serve as deft vehicles for depictions of life that is not only out of the way, but also out of the ordinary — whether in the realm of the fantastical, the naturalistic, the post-modern, or the slightly askew. With its eventual acceptance of outsiders, disproportionate number of nonagenarians, recognizable comic types, and frequent (if somewhat unpredictable) access to ferry service, Hunter’s island is in the ever-so-slightly askew category.

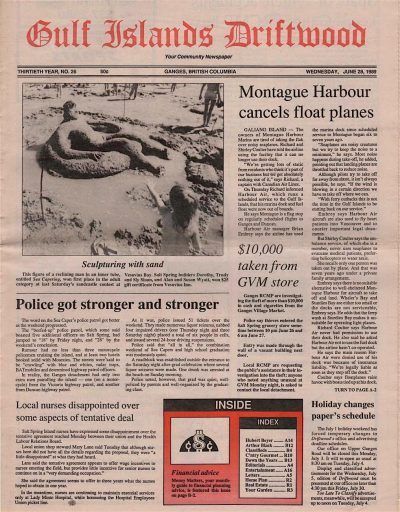

As Leacock’s Mariposa was inspired by his experiences in Orillia, Ontario, so too, Spinner’s Inlet has a real-life model — Galiano Island, where the (now retired) Vancouver Province newspaperman and his family once lived part time. Perhaps the nostalgic quality of the stories in Return to Spinner’s Inlet is a reflection of that: Hunter is fictionalizing a past rather than an ongoing experience. In any case, the eponymous fictional community is charming, comical, and well worth returning to.

*

Ginny Ratsoy is an Associate Professor of English at Thompson Rivers University specializing in Canadian literature. Recent courses have included Modern Canadian Drama and The Environment in Canadian Literature. She has published articles on theatre, playwrights, and small cities in British Columbia, and edited books, including Playing the Pacific Province: An Anthology of British Columbia Plays, 1967-2000 (Playwrights Canada Press, 2001, co-edited with James Hoffman); Theatre in British Columbia (Playwrights Canada Press, 2006); and, with W.F. Garrett-Petts and James Hoffman, Whose Culture Is It, Anyway? Community Engagement in Small Cities (New Star Books, 2014). Her latest academic publication is about a wonderful third-age learning organization, The Kamloops Adult Learners Society, in No Straight Lines: Local Leadership and the Path from Government to Government in Small Cities, edited by Terry Kading (University of Calgary Press, 2018), reviewed by Michael Lait in The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.