#719 Perpetual real estate fizz

Land of Destiny: A History of Vancouver Real Estate

by Jesse Donaldson

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2019

$20.00 / 9781772141443

Reviewed by Patricia E. Roy

*

Donaldson’s thesis is simple: “The history of Vancouver is the history of real estate” (p. 5). He persuasively argues that Vancouver has had housing crises almost continuously since its founding in 1886. “Our current state of affairs,” he explains, “is the result of a deliberate, century-long campaign on the part of wealthy development interests — and their enablers in government — to increase profits and line their pockets, one that regards ordinary, working Vancouverites as little more than collateral damage” (p. 5).

Donaldson’s thesis is simple: “The history of Vancouver is the history of real estate” (p. 5). He persuasively argues that Vancouver has had housing crises almost continuously since its founding in 1886. “Our current state of affairs,” he explains, “is the result of a deliberate, century-long campaign on the part of wealthy development interests — and their enablers in government — to increase profits and line their pockets, one that regards ordinary, working Vancouverites as little more than collateral damage” (p. 5).

After telling the story of the Three Greenhorns, so-named because the land – now downtown Vancouver — that they bought in 1862 was deemed worthless, Donaldson deals with the politicians and their friends who benefitted from inside knowledge about CPR plans to extend its line westward from the legal terminus at Port Moody. Inside knowledge was hardly necessary to know the inadequacies of Port Moody. Ships can only access its shallow harbour by sailing through the treacherous Second Narrows and steep hills arising almost from the shore line leave little flat land for railway and warehousing facilities. Moving to Vancouver, Donaldson vividly recounts the speculative boom that preceded a crash in 1913-14. He offers little on the interwar decades save for briefly describing an unsuccessful Better Housing Scheme, mentioning the Harland Bartholomew town plans for Vancouver and subsequent zoning laws, noting the hobo jungles of the 1930s, and then reporting the dire housing shortage immediately before, during, and after the Second World War.

Not until 1952, when Gerald Sutton Brown was appointed, did Vancouver have an official town planner. According to Donaldson, Sutton Brown “decided what was being built in Vancouver — period” (p. 108). While Sutton Brown conceived ambitious plans for urban renewal (slum clearance) and an elaborate freeway, others joined the protests of the people directly affected; the clearances ended before they were complete. Save for two viaducts the freeways never got off the drawing boards. Opposition to such changes contributed to the formation of The Electors Action Movement (TEAM), a new reform party at Vancouver City Hall that dominated city council after the December 1972 civic election. Sutton Brown resigned in anticipation of being dismissed.

The new city council rezoned industrial land around False Creek. Instead of selling it to developers, it leased it for the construction of a variety of housing from low rentals to luxury accommodation. This accomplished what Donaldson commends as “one of the most successful housing projects in Vancouver’s history” (p. 131). The approximately ten thousand “Vancouver Specials,” plain houses that were relatively inexpensive to build and made optimum use of narrow lots were another housing success. The account of their invention by Larry Cudney, a draftsman with a grievance against architects and changing opinions of them, is fascinating.

For Donaldson, such success stories are rare. In the late 1960s and the 1970s the gentrification of Fairview and of historic Gastown meant the loss of low-cost rentals. Those years also saw the introduction of the provincial Strata Titles Act which encouraged developers to build condominiums rather than rental units and, in what Donaldson calls “unscrupulous” acts, to convert existing rental buildings to condos (p. 121). Tenants’ protests and rent increases ultimately led to the NDP government in 1974 to introduce rent controls and a program to encourage private developers to construct rental housing. Donaldson rues that the developers “simply abused” the latter measure (p. 155) while the Social Credit government elected in 1975 watered down rent controls and ultimately abolished them.

Developers also invested in downtown real estate although it is not clear if the reference is to residential or commercial properties or both. Many investors were foreign. In the 1970s, the British were prominent but money from Asia, notably Hong Kong, was already being invested in Vancouver often through David Lam, a broker and later BC’s lieutenant-governor, who had emigrated from Hong Kong a few years earlier.

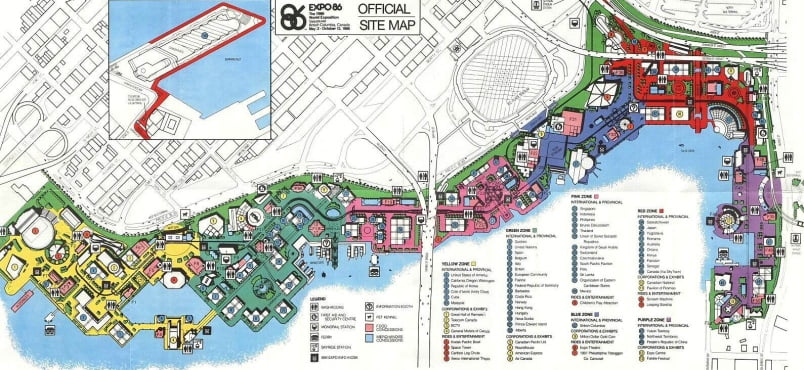

Then, as part of a strategy to recover from the economic recession in the early 1980s that hit property developers hard, the federal, provincial, and city governments created a “Pacific Strategy” to encourage trade and investment from Asia, especially China. A federal Business Investor Program gave investors and entrepreneurs a fast track to Canadian citizenship. Locally, the program’s highest profile was Expo ’86, a world’s fair. As well as drawing international attention to Vancouver, Expo dislocated hundreds of long-term residents of nearby hotels whose landlords hoped to cash in on the tourist trade.

After Expo closed, through a controversial arrangement, the provincial government sold the lands to Victor Li, the son of Li Ka-Shing, “the richest man in China” (p. 182) and head of Concord Pacific, a development company. Not only did the sale and its method have political repercussions but Donaldson asserts that “more than any other single event, the sale of the Expo lands forever changed the trajectory of Vancouver real estate” (p. 186). Concord Pacific sold portions of the land to other developers who, like it, built condominiums, many of which were sold to overseas investors in advance of construction before local residents had a chance to buy units. Donaldson rejects racist explanations for real estate prices that cut lower and middle-income Canadians out of the market and blames the province and the real estate interests such as Bob Rennie who hoped to stimulate the economy and fill their coffers. Because developing a condominium offered large profits and pre-sales financed construction, developers built them rather than rental housing and rents rose dramatically. As of 2019, rent control was a long-standing subject of debate and the vacancy rate was 0.8% (p. 219).

In 2010, Vancouver hosted another international event, the Winter Olympics. Many of the developers who lobbied for Expo also campaigned for the Olympics. Again, international exposure drew foreign investors into the Vancouver real estate market; in this instance they included “global criminals” who sought, not to live in the city, but to launder money illegally gained through such means as the drug trade (p. 223). Donaldson indicates that civic and provincial politicians also reaped rewards but the reference is to tax revenues not individuals.

Donaldson names many developers and their associates but declares Gordon Campbell to be “the best friend the development industry ever had” (p. 194) and calls his time as premier “an unmitigated disaster for affordability” (p. 222). Campbell began his working days in the development industry; moved to city hall as executive assistant to Mayor Art Philips; returned to development as an employee of Marathon Realty, the real estate arm of the Canadian Pacific Railway; formed his own development company; and got elected successively as alderman, mayor, member of the legislature, and ultimately premier. Donaldson cites instances of Mayor Campbell favouring his developer friends by such means as contracts, exemptions from development permits, and, without public tender, a grant of city-owned land for the construction of many thousands of units of “affordable housing.” In that case, fewer than 1200 units were built and the rent was at market rates.

The book seems comprehensive but there are gaps. Donaldson mentions how the City Council rejected the single tax idea of Henry George in the 1890s, but not that it later experimented with it to promote construction. The effects of the single tax on the pre-World War One building boom are considered in Daniel Francis’s L.D.: Mayor Louis Taylor and the Rise of Vancouver (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2004).

The anti-Chinese riot of 1887 is briefly described but the more serious anti-Asian riot of 1907 is not. The story of the narrow Sam Kee Building on Pender Street is told as is the removal of the Japanese and the confiscation of their property during the Second World War. Ironically, whereas one complaint about the Chinese in 1907 was the dilapidated housing of Chinatown, in more recent times it has been the absentee Chinese owners of luxury homes. The chapter on “Monster Houses,” however, refers to “Vancouver Specials” not to large houses.

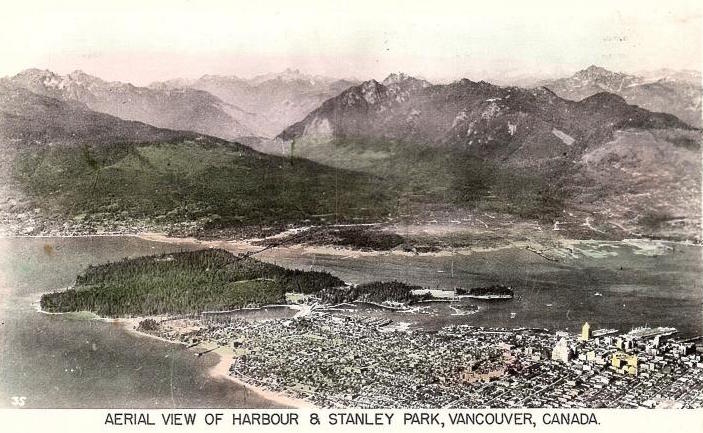

Save for an account of their dispossession from Stanley Park, there is no mention of the First Nations whose ancestors have been in the area since time immemorial. The story behind the government’s acquisition of the Kitsilano Indian Reserve in 1913 fits with Donaldson’s thesis, but is not mentioned. Donaldson will likely welcome the recently announced plans of the Squamish nation to construct a major project, including rental housing, on lands that they have regained.

While Donaldson has delved deeply into primary and secondary sources, his scholarship has been sloppy. A few examples must suffice. New Westminster was a colonial capital, but never a provincial one. If Premier Richard McBride spoke to the Legislature in 1919, it would have been an amazing feat; he died in 1917. The CCF did not fall apart in the late 1940s and early 1950s; it formed the official opposition in Victoria and almost formed the government in 1952. Frances Moren does not appear in any list of BC MPs or MLAs (p. 91). The Strathcona neighbourhood drew its name from Strathcona School which, in turn, was named after Donald Smith who became Lord Strathcona, not William Van Horne (p. 107). There was a federal election in 1935, but not a provincial one. A Bennett was elected premier in 1975, but it was Bill, not W.A.C. Bennett, his father. The provincial Liberals lost an election in 2017, not 2016. And while I was pleased to see some of my writings cited as sources, I can’t take credit for a history of the Vancouver Real Estate Exchange, interesting as that subject might be.

The jacket blurb announces that this is the first volume in a new series “celebrating the eccentric and unusual parts” of Vancouver’s history. Such a series will be welcome if they are written in as lively a manner as this volume and if they are fact-checked before going to the printer. Many factual errors in Land of Destiny detract from what is otherwise a timely and important study.

*

Patricia E. Roy, a native of British Columbia, is professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria where she taught Canadian history for many years. Her own research has been mainly in the field of British Columbia history and she is best known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989); The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007). All were published by UBC Press. Her longstanding interest in B.C.’s political history resulted in Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (UBC Press, 2012). Her latest book is The Collectors: A History of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives (Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum, 2018).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#719 Perpetual real estate fizz”

I really did enjoy your review. Thanks!

Comments are closed.