#715 Growing old on Hornby and Denman

Voices from Hornby & Denman Island Home Support, 1979-2019

by Megan J. Davies and Rachel Barken (editors)

Hornby and Denman Community Health Care Society, 2019

$10.00 / 978199278403

Available from Abraxas Books, Denman Island

Reviewed by Lee Reid

*

“Will there be help for me when I am old and in need?” is the enduring question that lies at the heart of this small and succinct book. In collaboration with the Hornby and Denman Islands Community Health Care Society, and edited by historian Megan J. Davies and sociologist Rachel Barken, Voices from Hornby and Denman Island Home Support answers that question. The book describes the history and work of Home Support Services from 1979 to 2019. Not only does the book briefly explore the positive impact of NDP and Social Credit government investments in rural elder care services in the 1970s and 80s, its equally colourful array of personal stories also reveal the negative impacts on seniors health through unstable and shifting government policies in the 1990s. By the end of the 90s through to 2019, the neo-liberal (Socred and Liberal) provincial governments implemented cuts to seniors services and programs that were managed through regionalized health councils (which then became the Health Authorities we are familiar with today). Those changes ultimately undermined the morale of Home Support workers and the health of their clients. Voices, however, is not a book about politics. It is a book about passion, purpose, aging, and community.

“Will there be help for me when I am old and in need?” is the enduring question that lies at the heart of this small and succinct book. In collaboration with the Hornby and Denman Islands Community Health Care Society, and edited by historian Megan J. Davies and sociologist Rachel Barken, Voices from Hornby and Denman Island Home Support answers that question. The book describes the history and work of Home Support Services from 1979 to 2019. Not only does the book briefly explore the positive impact of NDP and Social Credit government investments in rural elder care services in the 1970s and 80s, its equally colourful array of personal stories also reveal the negative impacts on seniors health through unstable and shifting government policies in the 1990s. By the end of the 90s through to 2019, the neo-liberal (Socred and Liberal) provincial governments implemented cuts to seniors services and programs that were managed through regionalized health councils (which then became the Health Authorities we are familiar with today). Those changes ultimately undermined the morale of Home Support workers and the health of their clients. Voices, however, is not a book about politics. It is a book about passion, purpose, aging, and community.

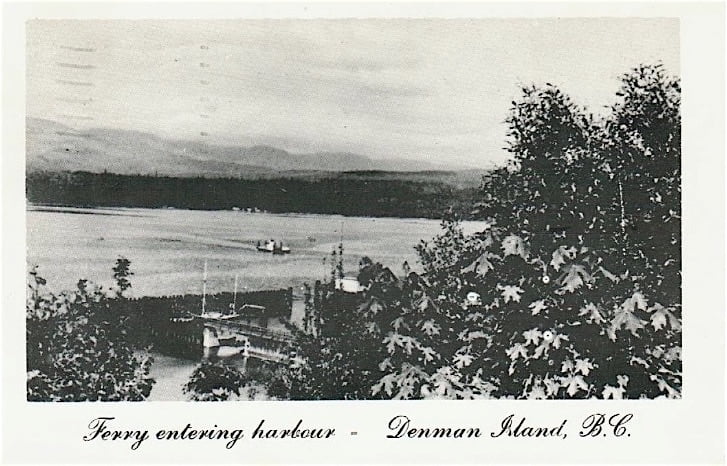

You could probably read Voices intensively in two ferry rides if you were delayed by a gale. The editors conceived the book from a serendipitous meeting on the ocean while sailing to Denman and Hornby Islands. I don’t recommend short rides, storms, or fast ferries with this gem of a book. Take time to savour it. You will feel touched by the poignant and at times comical weave of community stories about clients, about the lives and values of Home Support workers, about the spunky and no-nonsense Home Support administrators, and the challenging yet cherished land that infuses their lives. In fact, you might decide that each chapter deserves several ferry rides.

Isobel Mackenzie, the current BC Seniors Advocate, describes the rising economic hardship and escalating health needs of rural seniors in her report summarized here. In Voices, we discover just how disabling and expensive growing old can be when rural health care services like Home Support are cut, losses that are reflected in the advocate’s report. The stories in Voices span forty years of island Home Support Services, and are written in the oral tradition of people speaking their connections to the land and ocean and each other. Come on a ferry ride through the changing landscape of rural elder needs, as explored in the book…

Most baby boomers and Gen Xers ask themselves “Will there be help for me?” particularly as cultural ties to family or community weaken, and as more people live longer and live alone. In Canada, health research targets loneliness as a social determinant for poor health, dementia, and premature death. In the UK, loneliness is perceived as a national health crisis, motivating the British government to appoint a Minister of Loneliness, according to Suffering in Silence: Solving Seniors’ Isolation in BC.

In 1978, long before loneliness and loss of social engagement became high profile health issues for seniors, five Hornby Island women with nursing backgrounds elected to do something about it. Their proactive mission was to prevent declines in elder health by providing compassionate and practical home care that would enable rural seniors to remain in their homes. They founded Home Support Services on the islands. The spirit and gumption with which they accomplished this is as inspiring today as it was then. In the 1970s, the five women were already providing unpaid home and nursing care on Hornby and Denman Islands. Since the NDP and Social Credit political and financial will of the 1970s and 80s favoured services such as theirs, albeit with an underlying agenda to avert the more expensive options of hospitalising seniors or placing them in extended care facilities, the nurses achieved funding to form the Hornby and Denman Community Health Care Society.

Through that initiative, Home Support became an official community service with paid employment and training programs. Under the Health Care Society’s umbrella, a variety of home care services was launched, including handymen, housekeeping, nursing, mental health, youth counselling, palliative training and care. House and property upkeep was personalised to the needs of rural living. In effect, Home Support workers became the first responders who would sound the alert for people in crisis, long before ambulance and medical emergency services were installed on the islands. Although it took two ferries to transport a senior to medical care, home care workers provided that too. Home Support work was not for the faint of heart, but what emerged was a stronger community heartbeat.

This is and isn’t a book about state-of-the-art nursing care or social work, although Home Support Services certainly have provided that throughout rural BC. In October 2018, the islands Health Society invited Home Support workers and their clients to share their stories at two community meetings. Those stories, followed by personal interviews, articulated the historic values and trajectory of Hornby and Denman Island Home Support services in the book. Voices is a book about the hardships and creative ingenuity demanded by rural living, as well as the economic and health care challenges faced by aging populations on the Gulf Islands. We can surmise from the BC Seniors Advocate’s reports that similar stories could well apply across the province. It is the story of building an innovative system of health care that recognises the value of providing compassionate companioning to seniors.

In the late 1990s, cuts in health care funding under the Social Credit/ Liberal governments caused subsequent reductions in home care availability and companioning time with clients. What got cut, what suffered on the ground, was the scope of tasks the workers were allowed to do and their ability to maintain caring relationships.[1]

Long before the term compassionate community became the gold standard for larger Canadian communities to achieve (derived from Allan Kellehear’s Compassionate City Charter), Hornby and Denman Island Home Support was modelling it. Even the most reclusive or unfriendly clients and hermits responded to Home Support care. Beyond the scope of Voices is a resurgence of Home Support grassroots movements in rural towns and cities under that now familiar term “compassionate community.” In Voices, one nurse described her commitment to the work as this: “I felt that I had met something within myself … that I had a debt to people here … to the elders” (p. 44).

Motivated by the rural credo, “Always look after your neighbours” (p. 39), and fuelled by favourable political will in the 1970s and 80s, Home Support determined to keep people, especially clients with a degree of functioning capacity, out of costly nursing facilities. They knew that seniors were happier and healthier when they could live, age, and die in their homes. To place them in hospitals or residential care would increase government expenses, and the waitlists for extended care were long. Although caretaking people in their own homes was not an easy feat, through Home Support it was do-able and affordable. Home Support workers also understood that when seniors with frailty-related issues such as dementia were placed in hospitals to wait for an opening in extended care facilities, they could end up confused, distressed, and pleading to go home. This caused more pressures for the hospitals, which were already crowded with acutely ill and palliative patients.

Compared to the grim alternative presented by hospitalisation, we can see why Home Support workers cared deeply about elder residents/clients, who, in many cases, were their neighbours. One administrator described rural character as this: “I see that the happiest people are those who do something creative-cooking, painting, knitting, gardening, whatever” (p. 61). Home Support enabled seniors to live creatively.

Voices shows us that it is possible to be happy in a health care system. With courage and diplomatic ingenuity, the nurse administrators built a network of good relations among diverse ministries. They organised community fundraisers such as auctions, and they succeeded in eliciting funding from health councils and health authorities. They knew how to get and apply money specifically for personalized rural health care. They recognised, recruited and trained the hardy workers who would provide home care under challenging conditions, such as bad weather, impassable roads, or unfriendly clients living in isolated cabins with no phones or electricity or indoor plumbing. The workers, who were mostly women, were paid $13 an hour compared to the same care in hospitals for $20 an hour, a glaring inequity. “Women’s work is so undervalued,” comments one worker (p. 43). Home Support also sponsored a handyman service that subsidised men with carpentry skills to repair people’s homes.

Voices is a book that explicitly addresses the needs of aging populations on Hornby and Denman Islands, yet is applicable to seniors across BC. The stories reveal universal questions and losses that confront seniors: “How can I manage as my abilities decline? Who will support me when I don’t want to burden my family with my needs? Why would I want to live when I feel so lonely? Where and how will I go if I can’t keep my home? How can I let go of my pets, my routines; my land? How can I age and remain independent or mobile? How can I possibly ask for help when I never have, not until now?”

The stories from each worker in Voices share a passion for providing home care services to seniors and people in need on Denman and Hornby islands, no matter how unusual the needs or people were. In return, we hear deep gratitude from the clients for the kindness and practical help they received. It was as simple as that.

Here is a profile of island clients in the 1960s and 70s. If you are a baby boomer or a war veteran, imagine the client is you. If you are Gen X, then perhaps the profile describes your parents. You live quietly on your land. You live in a rustic cabin deep in the woods, or in a houseboat rocking on the ocean. You may carry emotional trauma; possibly sadness and fears from war. You may be physically injured. Although your life during the war may have been huge in scope (p. 29), and engaged with many people or causes, you appear to be a recluse who lives simply and self sufficiently off your garden or on food from the ocean. You might subsist on hunting and trapping.

Perhaps you avoid people because your social skills have shrunk and you suffer from anxiety. The courage it took for you to survive until now does not become evident until aging or loneliness reveal your scars. Those, you want to hide. Grief from previous losses or deaths rises to the surface, which makes you retreat more. Although your body may be toughened by years of hard work, you struggle to maintain your property because of aging or the injuries that accrue with rural living.

Some of you are born and bred on the Gulf Islands; others arrived during “the back to the land” quest for self-sufficient country living. Now in your late 60s or 70s, you may have arrived with the counterculture as a young well-educated boomer. Like other rural folks, you most likely led an interesting life. Many islanders can tell colourful stories about coast history — a history otherwise unknown and undocumented unless passed along through oral narratives and memory, or recorded in such books as Voices from Hornby & Denman Island Home Support. Perhaps, like many islanders, you are an urban refugee who could afford to retire while young, but you are not prepared for the rising health and living costs and the declining mobility that comes with aging. The average islander age is 55-plus, with more women than male inhabitants. Gender persuasions of all types arrive, seeking a rural home where people are open to diversity.

In the 1960s, 70s, 80s, and in some cases through to 2019, you live in a cabin with wood heat, intermittently running water, and an outhouse. Until you get too old to hike, you drive or boat to the only store on your island or near your home. Your garden and perhaps livestock provide much of your food. Maybe you have a phone. Electricity is variable. Some people still rely on kerosene lamps. On Hornby and Denman, there are no paved roads until the 1990s. Winters are notoriously long and boring.

In the 1960s and 70s, you might have fled the draft in the USA. You were opposed to serving in the Vietnam War or you were an activist for peace. Chances are that you arrived in your rural area as a couple or as a family, but through time, death, or separation, you ended up alone. Seniors adapt. “Lonely” becomes the new normal. You are unaware that loneliness undermines your health, but Home Support Services are critically aware of this. They aim to reduce loneliness by offering companionship while they do the chores you cannot keep up with. Nonetheless, you are resilient and independent, and so are “they,” the workers. They hike through woods and up impossible trails to be with you. Of course you never ask for help, but you become grateful for it as workers chainsaw and split your firewood from logs on the beach, clear your gutters and septic system, dig your gardens, care for your pets, clean your home, cook meals, ferry you to medical appointments, and help you to move around and bathe. The workers become your friends. You trust them.

Then, as now, rural seniors contended with shrinking social connections where, very often, their companions were animals and nature. In the 196os, 70s, and 80s on the Gulf Islands, there were no taxis or buses to ferry people around. There were no first responders, no fire station, no ambulance. There was no hospital. The medical centre might be in Comox, two ferries away. One island might have two stores and one pub. Home Support Services created outings to the one store and “golden lunches” at the pub or cafe to encourage you to socialise and break the monotony of your days. Fragility and poor health were not an option if seniors wanted to stay on their land. Home Support meant safety and security throughout your aging.

When it came to dying, there was no palliative care in the early 1970s. You had to rely on neighbours or friends or family or church, but many people lacked support. Home Support workers became poignantly aware that many of the clients they cared for might die while in their charge, and that home support care could last throughout a client’s old age, for twenty or thirty years. That too was part of the compassion and work. People wanted to die at home. Home Support Services stepped up to the plate and by the 1990s had founded the first palliative training for workers.

Workers realised that rural home care necessitated ingenuity and versatility; they might have to carry fresh water, chop wood, and solve home and health problems in unusual conditions. Work defined their identity and standing in the community, and they worked hard. In the 1970s and 80s, Home Support workers were trusted with the autonomy to make decisions that would optimise the capabilities of the clients no matter how odd that looked on paper. “Workers broke all the rules … it was not a problem” (p.16). Work was often governed by the (old fashioned) values that shaped the clients’ days, values that the workers learned from and appreciated. If clients needed a shower or the dog walked, it got done. Workers did the dishes, the vacuuming, cleaned the bathrooms, weeded gardens, brewed tea, and baked the birthday cake. They helped prepare people for residential care if they could no longer stay at home. As administrator Toby Krell describes the work in Voices, “I think anything you do can be creative … how you do what you do makes the difference” (p. 46).

By the 1990s, funders and ministries changed and a cost-cutting system of ticky-box regulations, pay cuts, stringent time sheets, and restrictions on type of care came into effect. Tension ensued, especially when clients’ needs did not fit the new terms of care or the worker’s limited hours of availability. Companioning or driving or pet care and birthday cake were cut (p. 59).

What began as “compassionate civic engagement” to keep people in their homes, when clients described homemakers as “The greatest … who make you feel good” (p. 13), gradually dwindled. Confidentiality was imposed, whether or not it suited the work. Issues of confidentiality limited workers’ ability to act as first responders because fear of liability prevented workers from talking with each other about the challenges they and their clients faced. The result was more loneliness for the very workers whose job was to reduce it.

Today, community care nurses employed by the health authorities still offer dedicated, albeit restricted, home health care to rural seniors. United Way also manages a system of home care called “Better at Home,” but services come with a fee that many low-income seniors cannot afford. There are also exciting new initiatives that attempt to fill the gaps in health care for vulnerable people. Nav-CARE, developed through UBC and the University of Alberta, provides home visits, companioning, and referrals for elders living with chronic illness. Increasingly, urban and rural neighbourhoods and friendship groups are also forming their own grassroots versions of compassion-based care for the terminally ill and the elderly, following the guidelines in books such as Share the Care by Cappy Caposella and Sheila Warnock (Touchstone Books, 2004).

In these times of global climate crisis and instability with provincial or federal funding, Voices from Hornby & Denman Island Home Support models an excellent template for seniors’ care and the restoration of community. If you were to ask the Home Support workers why they were so effective, they would suggest a timeless and simple recipe for success. “We have to revisit those things that made our home support special,” says Stephanie Wells, “good matchmaking, good chemistry between caregivers and clients, time for meetings with colleagues, and training workshops” (p. 63).

What can never be cut is the love it takes to do the job.

*

Lee Reid (née Batchelor), M. Ed, grew up in North Saanich and is now a clinical counsellor and writer in Nelson. In 2010, she retired from a career with Mental Health and Addictions Services in order to write about creative aging. She also facilitates workshops with seniors. In the secondary school system, she brings seniors and youth together in meaningful dialogues within the classroom. She is an activist for intergenerational education and an advocate for seniors’ health care. Her three books are From a Coastal Kitchen (Hancock House, 1980); Growing Home: The Legacy of Kootenay Elders (Growing Home Elders Press, 2016), reviewed by Duff Sutherland in The Ormsby Review; and Growing Together: Conversations with Seniors and Youth (Nelson CARES Society Press, 2018), reviewed by Luanne Armstrong. In 2018, The Ormsby Review published her childhood memoir, The Spider Hunters.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] See Paul Kevin Weaver, “The Regionalization of Health Care in British Columbia: Does Closer to Home Really Matter?” (B.A. essay, Simon Fraser University, 2003).

5 comments on “#715 Growing old on Hornby and Denman”

I thoroughly enjoyed this informative, knowledgable and insightful review written with love and intelligence. As a community care RN I know too well how cutbacks have negatively impacted Home Care.

As Chair of the Hornby & Denman Community Health Care Society, may I offer my thanks to Lee Reid for such a generous and comprehensive review!

Excellent review, Lee.

Comments are closed.